Pieter Coecke van Aelst (Netherlandish, 1502–1550) and workshop. Holy Family, ca. 1530–35. Oil on panel; 39 3/4 x 28 3/8 in. (101 x 72 cm). M — Museum Leuven (S/26/C). © KIK-IRPA, Brussels

Pieter Coecke van Aelst was a highly skilled and accomplished panel painter, yet many art historians associate him with a body of pedestrian paintings. Maryan Ainsworth, curator in the Department of European Paintings and co-curator of Grand Design: Pieter Coecke van Aelst and Renaissance Tapestry, examined this disparity through her close study of his painted works. I recently spoke with Maryan about Coecke's paintings and why the seven panel paintings on display in the exhibition are worthy of special attention.

Sarah Mallory: How do you, a curator of paintings, approach the work of Pieter Coecke van Aelst?

Maryan Ainsworth: Because Coecke was a peintre-inventeur (painter-designer), it is important to approach his production as the sum of all of its parts: painter, designer, cartoon-maker, etc. His production as a painter was not separate from, but part of, a development that ultimately led to his greatest achievements as a tapestry designer.

Sarah Mallory: How and why did you select the panel paintings included in the Grand Design exhibition?

Maryan Ainsworth: As the exhibition would emphasize Coecke's work as a tapestry designer, I aimed to show, with a limited number of key examples, how he developed as a painter alongside his work as a designer. I wanted to chart his progress from his earliest efforts within the workshop of his father-in-law, Jan Mertens van Doornicke, evidenced by his Adoration of the Magi triptych on view in the first gallery, up to his final documented work, the monumental Deposition triptych, in the collection of the Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga in Lisbon, Portugal.

The process of choosing seven key paintings from throughout Coecke's career involved first identifying the documented or semidocumented paintings (the Deposition triptych and the Last Supper in the collection of Belvoir castle, respectively) that served as the "linchpins" for Coecke's oeuvre. Then I studied firsthand as many paintings attributed to Coecke as possible and carried out a technical examination of them in order to understand their production process. From this I was able to identify common traits of technique and execution that united certain [works]. Ultimately, my choice of the seven works that came to the show was based on this process of selection.

Pieter Coecke van Aelst (Netherlandish, 1502–1550). Adoration of the Magi, ca. 1520–25. Triptych. Oil on panel, central panel; 41 3/8 x 27 1/2 in. (105 x 70 cm); wings each 41 3/8 x 11 3/4 in. (105 x 30 cm). Collection of Hester Diamond, New York

Sarah Mallory: Can you tell us about your approach to the study and analysis of Coecke's works?

Maryan Ainsworth: The initial study is of the surface characteristics of the painting—composition, figural style, and especially details of the use of color and brushwork. In Coecke's case, for example, he approached female and male faces differently, smoothly blending the brushwork of the former and using disengaged brushwork and bolder juxtaposition of contrasting tones to bring out almost a caricature-like nature of the latter. The heads of Christ in the paintings he also blended smoothly like the female heads.

I also studied the working technique of the paintings using infrared reflectography (IRR), x-radiography, and dendrochronology. IRR reveals the artist's underdrawing, or first sketch, on the panel for the composition and figures. In Coecke's case, the early to mature paintings consistently showed a drawing style that depended on squiggly lines with looped ends, looking a little like swimming tadpoles. The later paintings (for example, the Deposition triptych)...reveal Coecke's assimilation of Italian drawing techniques. Here, he has followed the lessons of Raphael and his pupils, especially Giulio Romano, and lavishes more attention on the modeling of the nude figures with parallel- and cross-hatching in the underdrawing stages to achieve the three-dimensional aspect of the figures.

Pieter Coecke van Aelst (Netherlandish, 1502–1550). Lovers Surprised by a Fool and Death, ca. 1525–30. Oil on panel; 14 7/8 x 21 1/8 in. (37.8 x 53.7 cm). Private collection

Sarah Mallory: How do Coecke's paintings fit within the larger tradition of painting in the North? Was he, in any respect, an anomaly?

Maryan Ainsworth: Coecke came onto the scene at a time of great changes in Antwerp. Initially, he trained in the prevailing local style called Antwerp Mannerism—a style of figures in exaggerated poses, highly decorative costumes, and startling coloristic effects. But with his developing interest in tapestry production that was influenced by Raphael's designs for the Acts of the Apostles series sent from Rome to Brussels to be woven there, he became strongly influenced by Raphael workshop designs and stylistic features. This new style has been termed "Romanism," and Coecke became a key proponent of it. Rather than an anomaly, I would say that Coecke was extremely au courant—very with the times!

Sarah Mallory: Can you tell us a little bit about the history, significance, and proliferation of Coecke's Last Supper? His Deposition triptych?

Maryan Ainsworth: Coecke painted his Last Supper, now in the collection of Belvoir Castle and generously lent to the show by His Grace The Duke of Rutland, in 1527 at a moment when Martin Luther's reformist ideas were circulating in Brussels and Antwerp through printed books and leaflets as well as through the sermons of his followers. Although the large and spectacular painting in the exhibition shows in its details a special attention to the iconography associated with the reform movement, the forty-five or so extant smaller copies of this painting are whittled-down versions of it not only in size but also in specific meaning. The copies attest to the popularity of Coecke's composition, and the many existing versions (there must have originally been even more!) were likely produced for sale on the open market in Antwerp and Brussels.

Pieter Coecke van Aelst (Netherlandish, 1502–1550). Last Supper, 1527. Oil on panel; 54 1/2 x 66 1/8 in. (138.5 x 168.1 cm). The Duke and Duchess of Rutland Collection, Belvoir Castle, Grantham, England. Photograph by Emile Gezels

The Deposition triptych, due to its monumental size, must have been specially commissioned for the altar of a church or important religious house (convent or monastery) in Antwerp. Unfortunately, there are no identifying features, such as donor figures or coat of arms, which provide clues to its intended location.

From remaining documents we learn, however, that the triptych was sold in 1585 to Antwerp dealers who brought it to Lisbon, where it changed hands again. It could be that it was hidden away and protected during the Iconoclasm of 1566 that destroyed so many religious works in the Low Countries. Although some of the figures—Saint John's face for example—were damaged intentionally, and the top and bottom of the central panel and its wings were cut down and then replaced, it is remarkable that this triptych has survived in relatively good condition. The triptych spent many years in a convent in Lisbon before being transferred in the nineteenth century to the city's Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga.

Pieter Coecke van Aelst (Netherlandish, 1502–1550). Deposition, ca. 1540–45. Triptych. Oil on panel, central panel; 8 ft. 7 1/8 in. x 5 ft. 7 3/4 in. (262 x 172 cm); left and right wings each 8 ft. 11 7/8 in. x 2 ft. 9 1/8 in. (274 x 84 cm). Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga, Lisbon (112). © Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga and Institute of Museums and Conservation, I. P. / Ministry of Culture. Photograph by Luis Pavão

Sarah Mallory: What, in your opinion, is the relationship between Coecke's paintings and his tapestries?

Maryan Ainsworth: Coecke's paintings and tapestries are related in a number of interesting ways. First of all, like his tapestry designs, certain of his paintings, for example, the Resurrection triptych (in the collection of the Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe in Germany), show the specific influence of Raphael's cartoons for the Acts of the Apostles series that came to Brussels in 1516 to be woven there. Coecke assimilated not only features of Raphael's compositions but also quoted specific figures.

When we look at Coecke's Deposition triptych, we can also consider the relative success of his paintings on a monumental scale vis-à-vis his tapestries. In the last room of the exhibition, the elegant figure of Mary Magdalen in the lower-right central panel of the Deposition triptych can be beautifully compared to some of the figures of Pomona in the tapestries of Vertumnus and Pomona. They are not far off in terms of relative size; they are especially close in the emphasis placed on the decorative details of their elaborate costumes that adorn these very elegant figures. Clearly in Coecke's mind, his approach to monumental paintings and tapestry design is similar.

Pieter Coecke van Aelst (Netherlandish, 1502–1550). Resurrection, ca. 1530. Triptych. Oil on panel, central panel; 28 1/2 x 22 in. (72.5 x 56 cm); wings each 28 x 9 1/4 in. (71 x 23.5 cm). Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe (153). © Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe 2013. Photograph by A. Fischer/H. Kohler

Sarah Mallory: What is your favorite work by Coecke?

Maryan Ainsworth: That's hard to say! They each have their special features that capture the viewer's attention. Perhaps, though, for me it is the Last Supper. Here, the varied expressions of the disciples, who are responding so emphatically to Christ's accusation that one of them will betray him, are riveting. The brushwork is exquisite and lively, and perfectly suits the exaggerated drama of the moment. Yet, it all takes place in a beautifully conceived and monumental space that adds a sense of solemnity and gravitas to the action taking place. I suppose I also especially like this work because we discovered so much about it in terms of the specific meaning of various details—one can really say that it expresses a moment in time when Martin Luther's reform movement was on the verge of eruption!

Sarah Mallory: Did you have any new insights about Coecke as a result of the research you did for this exhibition?

Maryan Ainsworth: There are so many paintings that are attributed to Coecke, and many of them are very meager in quality. He apparently had a thriving workshop where assistants—both talented and not so proficient—turned out paintings for sale on the open market. It was fascinating and a challenge to find the real Coecke amid all of these works. As a result, I grew to admire his work enormously. The added benefit was the opportunity to see some of his best paintings alongside his drawings and tapestries in our exhibition, and to consider his development in a more profound way. He clearly was aware of and acted on the new influences that he encountered in the artistic centers of Antwerp and Brussels (as well as on his trip to Constantinople), and he was a remarkable painter-designer who merits our focused attention, and deserves to be more widely known today.

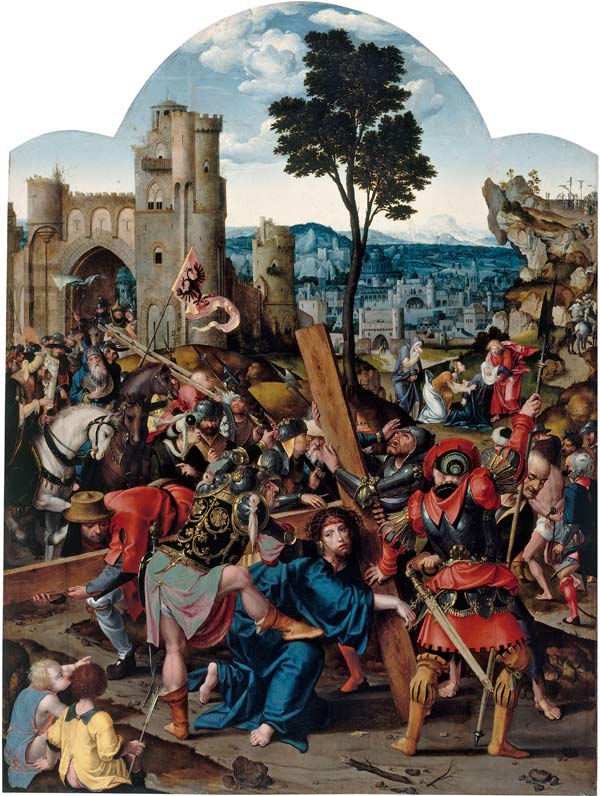

Pieter Coecke van Aelst (Netherlandish, 1502–1550). Christ Carrying the Cross, ca. 1520–25. Oil on panel; 42 1/4 x 31 1/2 in. (107.3 x 80 cm). Kunstmuseum Basel (1250). © Kunstmuseum Basel, Martin P. Bühler

Sarah Mallory: Anything else you would like to share?

Maryan Ainsworth: The artist Coecke, I feel, comes across beautifully in the exhibition space's "grand design" conceived by our talented exhibition designer, Dan Kershaw. Visitors can really experience the sweeping grandeur of tapestry as a medium when they visit the show. I hope that many more will take the opportunity to do so before Grand Design closes on January 11!