Alisa LaGamma and Howard French host a public interdisciplinary conversation in the exhibition Kongo: Power and Majesty. Photograph courtesy of James Green

On December 12, Pulitzer Prize–nominated journalist, author, and current Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism Associate Professor Howard French met with Alisa LaGamma, Ceil and Michael E. Pulitzer Curator in Charge of the Department of Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas, in the galleries of the exhibition Kongo: Power and Majesty for a public interdisciplinary conversation on the art of power, leadership, and global trade in Central Africa. The conversation brought together historical and contemporary perspectives on one of Africa's greatest civilizations.

Alisa LaGamma: As a specialist in African art for many years, it had become dismaying to be always mired in colonialism and Africa's exploitation by the West in the popular consciousness. I'm also very aware that Africa gets discussed in generalities, and I wanted an exhibition that would be more rigorous about grounding works in specific moments in history. We wanted to use art to consider how some of the most gifted and talented individuals in that society responded to historical developments over time.

Howard French: The most important thing this research does is confront a really persistent mindset that exists in the West—a kind of persistent disregard, an effort to diminish Africa in our mental space. This exhibition is like a brick thrown into the storefront of that kind of intellectual construct.

The French philosopher-historian François Furet wrote about the "second illusion of truth," the idea that the world is the way it is because it had to be that way. This exhibition has strong evidence against that: here's Kongo, a civilization with roots as far back as the third or fourth century, with a great many cultural achievements well before the arrival of Europeans. They traded with Portugal on the basis of absolute self-confidence, with no doubt of their full equality vis-à-vis these newcomers who showed up on their shores, and left a written record that reflected their side of this experience.

Alisa LaGamma: We deliberately opened with works that confound your expectation of what Africa is: elegant luxury textiles and carved ivories produced at the Kongo court and sent out into the world as diplomatic gifts. This side of African history doesn't get told very often. Regional leaders were very proactive and strategic about their engagement with the world: [the] first ivory trumpet was commissioned by the Kongo King Afonso I as an offering to Pope Leo X to underscore his alliance with the head of Christendom; an illuminated book of coats of arms gives us a snapshot of the great world powers at that moment in history. We get the sense that Kongo is a player in the world, with a vigorous correspondence underway between Mbanza Kongo and major European capitals.

The coat of arms of the Kingdom of Kongo is featured at the bottom right; the others are of Scotland, Poland, and Bohemia. António Godinho. Livro da Nobreza e da Perfeição das Armas dos Reis Cristãos e Nobres Linhagens dos Reinos e Senhorios de Portugal (Book of Nobility and of the Perfection of the Coat of Arms of the Christian Kings and Noble Lineages of the Kingdoms and Landlords of Portugal), ca. 1521–41. Portugal, Lisbon. Pigment and gold on parchment; H. 17 (43 cm) x W. 12 1/2 (32 cm) x D. 2 1/2 in. (5.5 cm). Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo, Lisbon

One of the things that I love about these works is that they come out of a moment full of possibilities: African leaders are seizing an opportunity to reposition themselves in a larger global context. Later, their standing is compromised by the introduction of the transatlantic slave trade, the huge destabilizer in this region from that moment forward.

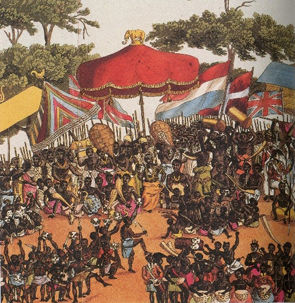

Howard French: I'd like to add another African piece to this global context: in West Africa, the kingdoms of Asante and Dahomey [Benin] weren't willing to merely receive things from Europe, but exchange and interact with a sense of agency and with a view to preserve their sovereignty, similarly sending out diplomatic missions. This exhibition, in the broader sense, is about how that comes undone, but also about the many forms of resistance that take place.

Left: A detail of the Asantehene Osei Bonsu of Kumasi seated with officials from T. E. Bowdich's 1819 book Mission from Cape Coast Castle to Ashantee

Ten years before [this encounter], the Portuguese invented the caravel, a ship allowing mariners to tack against the wind in a way that previous technology did not easily allow. This put Portugal, geographically speaking, on a collision course with Brazil, an extraordinarily rich, natural environment which fires the Portuguese imagination with dreams of exploitation. The caravel enabled Portugal to complete a very fateful triangle, setting into motion disastrous events for African civilization.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder (Netherlandish, ca. 1525–1569). Three Caravels in a Rising Squall with Arion on a Dolphin from The Sailing Vessels, 1561–65. Engraving and etching; first state of six; 8 11/16 x 11 1/4 in. (22 x 28.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Alexandrine Sinsheimer, 1959 (59.534.24)

Furet's theory becomes interesting in telling this story of European imperialism, because there are lots of "accidents" that become deeply determinative of outcomes. One can imagine if Kongo had another generation or two of isolation, or contact under somewhat different circumstances, it might've been able to advance its statecraft sufficiently and survive. It took the British the entire nineteenth century to subdue the Asante, partly because they had such a capable state, but also because Britain was spread thin with missions elsewhere. These are all accidents of history, timing, and the like. As it is, this is still an incredible story of resistance.

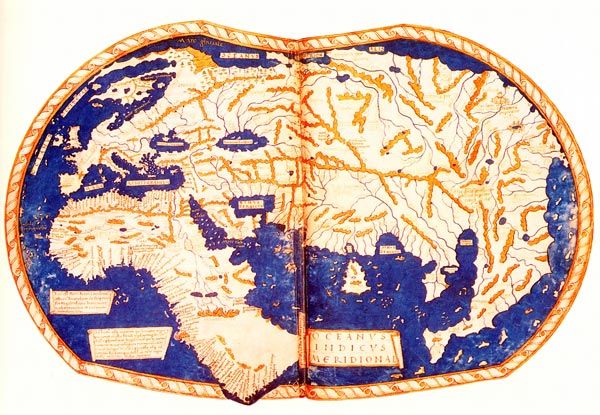

Henricus Martellus (Italian, active 1459–96). World Map Ca. 1483, late 1480s. Image via Wikimedia Commons

Alisa LaGamma: It's astonishing to me that, given the instability that ensues as a result of this particular region's exploitation through the slave trade, local leaders clung to self-governance until the second half of the nineteenth century. It's pretty incredible.

Despite the preponderance of late-nineteenth-century material culture from sub-Saharan Africa, we haven't really thought about it as archival evidence. To me, these are primary sources just as valuable [as texts] because they really reflect the hopes, aspirations, and creativity of a people through a very high level of visual expression.

Curiously, most early collected works are secular decorative arts; there was enough of a sense of the potency of religious artifacts that they weren't taken by traders until after the nineteenth century as curios. By then, all Kongo artworks are relegated to obscurity in anthropology museums, which isolated non-European creativity. This shows how subjective our categorization of culture has been; a great masterpiece at one moment in time then becomes a historical footnote.

Kongo raffia textiles are at times misidentified as Portuguese and Southeast Asian in origin. Luxury cloth: cushion cover, 16th–17th century, inventoried 1670. Kongo peoples, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kongo Kingdom; Angola; Republic of the Congo. Raffia; 19 1/4 x 19 7/8 in. (49 x 50.5 cm) [measurements including the larger corner tassles 51 x 52 cm]. Kungliga Samlingarna, Sweden

Howard French: I would like to argue that this is not just about Europe vs non-European. I think Africa occupies a very special place in this [problem] that you've identified, and I called it a "systematic disregard," an active effort to disregard Africa, in that it requires energy. Whenever Europeans encountered an African culture or civilization they considered impressive or sophisticated, they began theorizing about its origins, inevitably concluding that it must've been the work of outsiders. If we found something great in Africa—from Egypt to Zimbabwe—it had to come from some non-African source.

Alisa LaGamma: The works in this first gallery are so "unexpected" that people ask, "Have they been influenced by Europe?" But this tradition was firmly in place by the time of the arrival of the Europeans. To create carved ivories with this kind of complexity and decoration, to have that level of skill in that idiom, the artist would've had to train in a specialized profession for generations.

The takeaway from the first room is how responsive local artists were to outside ideas: they produce beautiful cloths for their own consumption, but they are very open to using European decorative arts formats for gifts to send back to Europe. There's an assumption that there isn't much change in African creativity, but artists are always melding interesting ideas.

One of the things I find very moving about the works in the final gallery is that they're such a response to the experiences of Kongo communities. So depleted of their energies and populace, by the nineteenth century you have this artistic explosion of what are essentially visual prayers for revitalization; the universal imagery of a seated woman with infant takes on new urgency. Mangaaka represent a movement developed in the Chiloango River region as a defensive shield against aggression from Portugal, the Netherlands, France, Britain, and Belgium. Effective for roughly twenty years, they are then swept away when Europeans determine that to undermine local authority, these shields need to be eliminated. The fifteen that we've been able to assemble is really all that's left.

Gallery view of six of the fifteen Mangaaka power figures in the exhibition. Photograph by Peter Zeray

Howard French: Chinua Achebe's great novel Things Fall Apart describes a similar circumstance, writing, "The white man . . . came quietly and peaceably with his religion. We were amused at his foolishness and allowed him to stay. Now he has won our brothers . . . he has a put a knife on the things that held us together and we have fallen apart." The Europeans understood the importance of religion, particularly the need to destroy this force, this agent of cohesion in African societies and means of rallying people in times of great stress.

Fétiches du Bas-Congo (Three Power Figures [Minkisi]), photograph, 1913–14; postcard, early 20th century. 5 1/4 x 3 3/8 in. (13.4 x 8.6 cm). Holly W. Ross Postcard Collection, Princeton

I also noticed in my coverage of Mobutu [Sese Seko]'s last years in Zaire [modern Democratic Republic of the Congo] that Angola—by this point obviously an independent country—becomes an agent in destabilizing Congo, or Zaire. It had designs of its own on Congolese wealth, and the pattern was absolutely an echo of what had happened five hundred years earlier. When Kongo began to resist Portugal [in the seventeenth century], the latter went south to what is Angola today, which was less organized in terms of polities and state formation, and used it as a base to attack these stronger peoples to the north. This becomes the modus operandi of imperialists throughout Africa for the succeeding centuries and, again, after independence.

Unable to perceive complexity, we often reduce African art and narratives to the simplest of storylines; for example, this is primitive art par excellence. It's "scary," but there is nothing accidental, or primitive about it, everything is carefully conceived. There is history here. The Africa that we are so familiar with—invisible or a place of misery—isn't the Africa that's always existed nor is it the Africa that need be. This effort is a triumph because it drags this topic in the direction of the specificity which it so desperately deserves.

Editors' Note: This conversation has been edited and condensed from the original. Full audio recording of the discussion here: