Exhibition curator Alisa LaGamma, at left, with award-winning singer-songwriter Angelique Kidjo in the exhibition Kongo: Power and Majesty. Photograph by Peter Zeray

Alisa LaGamma, curator of the exhibition Kongo: Power and Majesty, recently met in the galleries with Angelique Kidjo, Grammy Award–winning singer-songwriter and activist, to discuss the works of art on view—and the prominent theme of female power. They responded to questions from Graduate Intern Helina Gebremedhen.

Helina Gebremedhen: The idea of female power is represented in several different ways in the works in this exhibition, ranging from the so-called mother and child figures and ancestral shrine figures to elegantly carved ivory staff finials. Alisa, could you tell us a bit about this range?

Alisa LaGamma: One of the things that's fascinating when looking at the works of art commissioned by Kongo leaders and their communities is that although they were male leaders, they understood that people trust women as the ones who look out for everybody's welfare. Women are the nurturers in society, and so even the most ambitious chiefs and kings incorporated images of women in their leadership insignia, such as staffs of office with extremely expensive ivory finials depicting women at the summit.

When male chiefs died, and they needed to be glorified and their importance as ancestors celebrated, beautiful kneeling female shrine figures were positioned at their burial sites to comment on their new role as influential ancestors. The men are trying to instill trust in their role as leaders by drawing upon some of the qualities that are often associated with women.

Left: Carved ivory staff finials, several of which have been attributed to the Master of Makaya-Vista, on view in the exhibition. Photograph by Peter Zeray. Right: Master of Makaya-Vista. Staff Finial: Kneeling Female Figure, 19th–early 20th century. Kongo peoples; Woyo group, Democratic Republic of Congo, Republic of Congo, or Cabinda, Angola. Ivory; H. 5 3/8 in. (13.7 cm), W. 1 3/8 in. (3.5 cm), D. 1 3/8 in. (3.5 cm). Private collection

Helina Gebremedhen: And vice versa: many of these works depicting female figures also incorporate typically male symbols of power or authority, like the mpu woven cap.

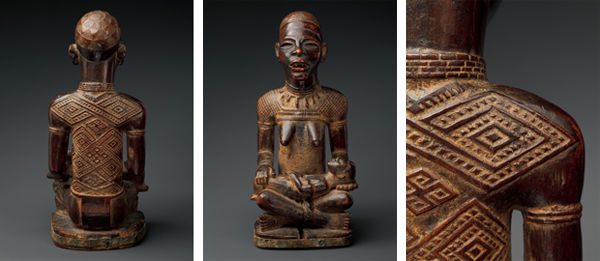

Master of the Boma-Vonde Region. Seated Female Nursing Child, 19th–early 20th century. Kongo peoples; Yombe group, Kai Kuinba village [?], Democratic Republic of the Congo, Republic of the Congo, or Cabinda, Angola. Wood, kaolin, glass. Collection of Drs. Daniel and Marian Malcolm, Tenafly, New Jersey

Alisa LaGamma: Yes. Even though the depictions are of women, they are being framed with the symbolism of male power. They wear the crowns of Kongo male chiefs, which is not something that you would have seen ordinary women wearing. They're also represented enthroned, seated in this posture of how a great king receives people at court. We're getting signs from the artist that these women are highly influential figures who are not only mothers; they have a larger role in society.

Helina Gebremedhen: Angelique, you've described your most recent album, EVE, as a "remembrance of African women I grew up with, and a testament to the pride and strength that hide behind the smile that masks everyday troubles." It's all about celebrating women in Africa and the individual and collective power they hold. What does female power mean to you?

Angelique Kidjo: I was raised with three powerful women, and these sculptures remind me a lot of the relentless commitment and resilience of the African woman. Our story, however, has often been told by others—that of Eve has been told by Adam and his peers and so on—and the first person that jumps in to tell your story owns your identity and decides what you're able to do.

In these figures, these women refuse that. They are Eve in their own right: they prove their power and their history by the way they sit and by the way that the kings recognize them. These female sculptures are a strong message for any woman, because suddenly, you see yourself.

Left: Seated Female Supporting Figure with Hand raised to Mouth, 19th–early 20th century, inventoried 1916. Kongo peoples; Yombe group, Cabinda, Angola. Wood (Canarium schweinfurthii Engl.), plant fiber, glass, leopard claw, kaolin, pigment. Museu da Ciência da Universidade de Coimbra, Portugal. Right: Power Figure: Standing Female with Child (Wife of Mabyaala?) (Nkisi), 19th century, inventoried 1885. Kongo peoples; Vili group, Loango coast, Cabinda, Angola. Wood, beads, glass, fiber, copper, resin. Collection Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen, Netherlands

Helina Gebremedhen: Alisa, in the catalogue, you describe how the male Mangaaka figures displayed in the same gallery space as the female figures were created as responses to a sustained onslaught of outside threats including colonial raids and warfare. Do these female figures also seek to address a societal concern?

Alisa LaGamma: Yes. One of the things that we wanted to do for the first time with showing these masterpieces of Kongo sculpture—masterpieces by any standard—is that they are created as a response to a real crisis that develop[ed] in this particular region, when communities [were] really heavily depopulated as a result of the transatlantic slave trade, foreign epidemics, and later, the removal of people for forced labor under colonialism.

A very significant drop in the life force of these communities occurred, and these works are directly coming out of that situation. Women were really looked at as the go-to source for revitalization and regeneration, and there were very heavy responsibilities on their shoulders. We know that many of these works were actually created to assist with women having children. It's a very poignant thing to understand that these works are not just decorative; they come out of the most profound need that a society has—survival.

Angelique Kidjo: The way these statues are placed with the Mangaaka power figures—who represent power and justice and defend against the colonial threat—also reminds me that they cannot succeed without the women. The large power figures on one side work together with these small ones. In my song Nanaé, I ask, when there is conflict, or a war, and all the men leave the village or the city, who stays behind and keeps society together? Women.

Alisa LaGamma: We celebrate that selflessness that women have, in giving back to their communities, instead of just taking them for granted.

Helina Gebremedhen: What parallels do you see, if any, between this historic symbolism and the role of women in contemporary Africa? Angelique, do you see this in your activism with the Batonga Foundation? What is the continued impact of these figures today?

Angelique Kidjo: Absolutely! The issue of women everywhere is always about the future for our children. How we can create a better world, and how we work so hard to make sure that when our last day on earth comes, we can rest in peace knowing that we have done everything in our capacity for our children to be able to take over from here. That commitment of women in the world—not just in Africa—it's amazing. It's the one thing that keeps coming back to me.

Alisa LaGamma: It's a leitmotif that is very much affirmative and hopeful. It's about the future. One of the messages of this exhibition is that artists really sought to come to the rescue of their communities through the creation of these works, through the carvings of these beautiful, elegant, refined women that were ideals of social comportment, that people looked to as role models in times of great stress. Creating these larger-than-life presences of male leaders to act as guardians—I mean, artists were really in the vanguard of seeking to heal society. So I think that that's an important message.

Angelique Kidjo, at left, and Alisa LaGamma, discuss a female power figure in the galleries. Photograph by Peter Zeray

Angelique Kidjo: I'd also say that these pieces of art are also reclaiming their humanity, then and now. Because in order to do what happened—to conduct these brutal raids, to turn people into slaves, and to justify it—you have to dehumanize them. And I'm glad we see all these works, because for years, the saying and the cliché was that Africa has no art, no civilization, and no history. Today we are realizing that it has been put away in order to pursue another purpose.

Alisa LaGamma: I agree; people tend to oversimplify their understanding of Africa, with this cliché that artworks were never created as art per se. Well, we have to redefine our understanding of what art is. Art is the thing that touches, the things that matter the most in our existence, and [what] inspires us to rise above our ordinary behaviors. Here, we're trying to move beyond an overgeneralized understanding of Africa and Kongo and explain that it's home to one of the greatest art traditions that exist.

Master of Kasadi. Seated Female Supporting Figure with Clasped Hands, 19th century, inventoried 1898. Kongo peoples; Yombe group, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Republic of the Congo, or Cabinda, Angola. Wood, metal, glass, kaolin, pigment. Ross Art Management, LLC, New York

Helina Gebremedhen: You've both described these sculptures as "socially engaged" art. What role can art play in creating change?

Angelique Kidjo: Art challenges you to think about the status quo. People come in, and sometimes they're uncomfortable because this brings them to the history of these regions. But it makes us ask ourselves how we can make this different, if we have the choice and the chance to approach the relationship between us again. You don't even notice it, but your perspective has been changed a little bit.

That's why I say we need more and more of these kinds of exhibitions. Art frees you, it gives you a different perspective, and it gives you a voice. It gives you power. I want, after this exhibition, to go home and look at myself and say I can do anything I put my mind to. I want that power to be instilled in me.

Alisa LaGamma: And I think, as Angelique is saying, we can have all these ideas in written form but until you experience it through music or visual arts, it can remain too abstract and ethereal. Visual or performed art can be an incredibly powerful catalyst to really move us personally.