Triple crucifix; central figure: 16th–17th century; top and bottom figures: 18th–19th century. Kongo peoples; Kongo Kingdom, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Republic of the Congo, or Angola. Central figure: brass (open-back cast); top and bottom figures: brass (solid cast); nails: iron (forged), copper, brass (forged), wood, ultramarine pigment, H. 10 1/4 in. (26 cm), W. 5 3/4 in. (14.5 cm), D. 1 in. (2.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Ernst Anspach, 1999 (1999.295.15)

The exhibition Kongo: Power and Majesty, on view through January 3, 2016, provides an opportunity to consider the remarkable cross-cultural artistic interaction that took place between Kongo and Portugal from the fifteenth through the eighteenth century.

Christian imagery was first introduced to Kongo by Portuguese navigators, who associated the symbol of the cross with political power and military might. When the navigator Diogo Cão reached Kongo in 1483, he erected a padrão—a stone monument featuring a cross, the Portuguese royal coat of arms and an inscription—to make claims of possession for Portugal. Later destroyed, it was similar to the one on view in the exhibition.

Left: Padrão de Santo Agostinho (Standard of Saint Augustine) (detail), ca. 1482. Portugal. Limestone; H. 84 5/8 in. (215 cm), W. 12 1/4 in. (31 cm), D. 12 1/4 in. (31 cm). Museu Etnográfico — Sociedade de Geografia de Lisboa, Lisbon

The political claims expressed by the padrão were soon complemented by an overt connection between the cross and military power. Rui de Sousa, captain of Portugal's 1491 mission to the Kingdom of Kongo, offered military support to its king, Nzinga a Nkuwu, to suppress a provincial rebellion. In this elaborate ceremony, de Sousa gave the king a military banner featuring the "sign of the most true cross." The Portuguese assured the king that the banner would enhance his powers and guarantee victory over his enemies. Probably perceiving the banner as a war talisman, King Nzinga had one of his men carry the "banner of Christ" in procession to his palace, while others fanned it to prevent dust or "other filth" from soiling it, a clear act of reverence.

It is possible that this "banner of Christ" displayed the cross of the military Order of Christ, formerly the Knights Templar, which spearheaded navigation along the coast of Atlantic Africa. The red cross of the Order frequently appeared on the sails of Portuguese vessels, as recorded in the Livro de Lisuarte de Abreu in The Morgan Library and Museum, and it was soon incorporated into Kongo visual culture.

"Armada de Tristão da Cunha," in Livro de Lisuarte de Abreu, MS M.525, 1560s, Pierpont Morgan Library

The first Christian artworks arrived in Kongo through a series of royal gift exchanges. When King Nzinga converted to Christianity in 1491, the Portuguese supplied him with everything necessary for the maintenance of the faith, including priests, crosses, and devotional panel paintings bearing images of the Virgin Mary and various saints.

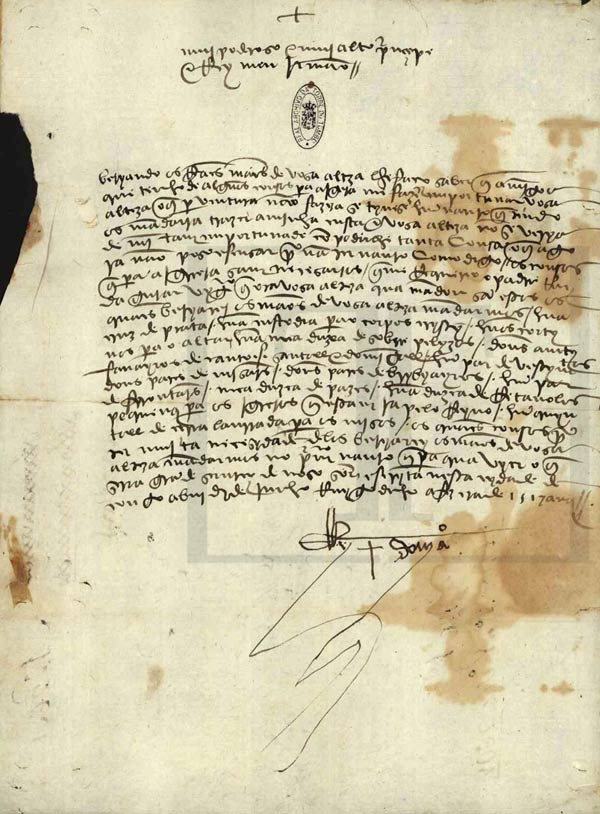

Royal requests for European Christian art continued throughout the sixteenth century. In a 1517 letter to the Portuguese king Manuel I, Kongo king Afonso I—King Nzinga's son—asks, among other things, for "a silver cross" and "a dozen small altarpieces."

Letter from Afonso I of the Kongo to Manuel I of Portugal requesting religious paraphernalia, June 8, 1517. Kongo Kingdom. Ink on paper; 8 1/4 x 11 1/4 in. (21 x 28.7 cm). Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo, Lisbon

Although these objects have not been identified, the magnificent gilded-silver processional cross that Manuel I donated to the Cathedral of Funchal (Madeira) gives us a sense of the kinds of objects that circulated in the Lusophone Atlantic at this time and what might have been sent to the Kongo.

Processional cross (detail), first quarter of the 16th century. Museu de Arte Sacra do Funchal (Madeira), MASF56

Afonso I made Christianity Kongo's state religion. He claimed that divine intervention helped him defeat his brother Mpanzu a Nzinga, who rejected Christianity, in a battle to secure the kingdom of Kongo. As a result, he raised a monumental wooden cross in the capital city of Mbanza Kongo to assert his political and spiritual authority, for he had learned from the Portuguese missions to associate the cross with political, military, and religious power. With his conversion, however, the Portuguese demanded destruction of traditional Kongo religious objects, which they labeled as "idols." Kongo kings and European missionaries distributed crosses, medals, rosaries, and Christian images to replace these so-called idols, fostering their use as charms.

This kind of substitution was possible because Afonso I Africanized Christianity by identifying it with traditional religious beliefs. During this period, crosses were worn as signs of devotion and placed on altars and graves, as they were in Europe, but, like traditional Kongo religious objects, they also functioned as amulets of protection and good fortune and were used to cure illnesses.

We know from Inquisition records that locally manufactured crucifixes were being traded illegally in Angola in the 1590s. Although it is difficult to date early Kongo Christian crucifixes, portable prestige pieces such as the solid metal crucifix below were typical of those produced during the sixteenth or seventeenth century. This crucifix exemplifies many of the artistic and theoretical achievements of Kongo artists as they creatively and independently engaged with European art for their own purposes and on their own terms.

Crucifix, 16th–17th century. Kongo peoples; Kongo Kingdom, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Republic of the Congo, or Angola. Brass (solid cast); H. 10 3/4 in. (27.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Ernst Anspach, 1999 (1999.295.7). Photograph by Peter Zeray

The figure of Christ is shown here as an African, a powerful and enduring idea that was later central to the eighteenth-century religious movement led by the noblewoman Dona Beatriz Kimpa Vita. The depiction of Christ's body reveals novel developments; the artist used an African style and mode of representation that reinterpreted European iconography. Christ's loincloth seems to be represented as a locally crafted raffia cloth wrapper with an X-shaped cross design framed on each side by vertical lines. The X-shape, a traditional Kongo symbol, heightens the power of the crucifix to communicate with the other world.

Significantly, the wrapper is paired with an etched diamond design, which recalls traditional textile patterns visible on other objects on view in the exhibition. The textile pattern forms a raised border around the crucifix, perhaps relating to the practice of wrapping sacred objects as well as the deceased in luxury textiles.

Left: Crucifix (detail), 16th–17th century. Kongo peoples; Kongo Kingdom, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Republic of the Congo, or Angola. Brass (solid cast); H. 10 3/4 in. (27.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Ernst Anspach, 1999 (1999.295.7). Photograph by Peter Zeray. Right: Luxury cloth, 17th–18th century, inventoried 1709. Kongo peoples; Democratic Republic of the Congo, Republic of the Congo, or Angola. Raffia, pigments; 39 1/8 x 35 7/8 in. (99.5 x 91 cm), excluding unwoven fringe. MIBACT— Polo Museale del Lazio, Museo Preistorico Etnografico Luigi Pigorini, Rome (5472)

Secondary figures are located above and below Christ and on each arm of the cross. The practice of adding these figures was possibly suggested by the depiction of saints on European processional crosses, such as a painted Italian example in the Met's collection.

Left: Crucifix, 16th–17th century. Kongo peoples; Kongo Kingdom, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Republic of the Congo, or Angola. Brass (solid cast); H. 10 3/4 in. (27.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Ernst Anspach, 1999 (1999.295.7). Photograph by Peter Zeray. Right: Master of the Orcagnesque Misericordia (Italian, active second half 14th century). Crucifix, 1370–75. Tempera on wood, gold ground; 18 x 13 1/4 in (45.7 x 33.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Samuel H. Kress, 1927 (27.231ab)

Kongo artists, however, developed this practice far beyond any European precedent, varying the number, placement, and pose of figures, and art historians continue to advance a variety of interpretations for them. Are they praying, making gestures of submission, or kneeling in poses of respect? Do they represent saints, intermediaries, attendants, supplicants, or deceased figures? Whatever meanings these figures may once have held, they and the other elements discussed above testify to the creation of a potent new form of art—Kongo Christian art.

Saint Anthony of Padua: A Case Study in Kongo Christian Art

From the fifteenth through the eighteenth century, Saint Anthony of Padua (1195–1231) was as popular in Kongo as he was in Europe. Born Fernando Martins de Bulhões, he became a Franciscan friar, preaching in his native Portugal before moving to Italy. Saint Anthony is a patron saint of Lisbon, which celebrates him with an annual procession, or Festa, on June 13.

After exiting the Igreja de Santo António, the lifesize statue of St. Anthony is placed on a pickup truck to journey through Lisbon; bearers carry smaller images of saints on flower-covered litters, or platforms, much as they would have been processed in Kongo centuries ago. Photographs by Kristen Windmuller-Luna, June 13, 2014

During the celebrations, chanting priests and singing worshipers follow the lifesize sculpture of the saint as it winds through Lisbon's cobbled streets from the site of his birth toward the cathedral. At night, revelers feast on grilled sardines in homage to the saint's famed "sermon to the fishes," during which he preached to fish so convincingly that heretics converted and the faithful rejoiced.

Saint Anthony processions also occurred in Kongo. In a 1702 letter, Father Lorenzo da Lucca described how the procession of a fine Brazilian-made sculpture of Saint Anthony of Padua was the highlight of the Feast of the Blessed Rosary at a Capuchin mission in Kongo. As we only have still images documenting Kongo processions, contemporary Saint Anthony processions like those in Lisbon viscerally suggest their original appearance, sounds, and movement.

Portuguese missionaries first introduced the saint to Kongo after King Nzinga's 1491 conversion to Catholicism. By 1595, the saint was the focus of an elite confraternity and the namesake of a royal church in the capital city of São Salvador (Mbanza Kongo). However, it was Capuchins like da Lucca who widely popularized the saint in the mid-seventeenth century by distributing pendants with his likeness.

Three metal sculptures incorporating pendants of Saint Anthony are on view in Kongo: Power and Majesty. The first is an unusual crucifix from the Metropolitan's collection. Made of wood, it is decorated with inlaid metal pattée crosses, likely symbolizing the Order of Christ.

A metal bar is used to affix a pendant of Saint Anthony by its hanging loop to a wooden cross. Cross: Saint Anthony of Padua; pendant figure, 16th–18th century; cross, 19th century. Kongo peoples; Kongo Kingdom, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Republic of the Congo, or Angola. Solid cast brass, lead-tin alloy sheet, wood; H. 12 3/4 in. (32.4 cm), W. 7 1/4 in. (18.4 cm), D. 1 in. (2.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Ernst Anspach, 1999 (1999.295.14). Photograph by Peter Zeray

At the center is a metal sculpture of Saint Anthony holding the Christ child on an open book; the pose evokes how the infant Jesus was said to have appeared to the saint while he read. Additionally, the miraculous return of a stolen psalter gained Saint Anthony his reputation as the patron saint of those who seek lost items. After his death, he was credited with the safe recovery of countless items, leading to his swift canonization just a year after his death. The metal figure has a small loop on its back; prior to being attached to the wooden cross, it was worn as a pendant.

Pendant: Saint Anthony of Padua, 16th–19th century. Kongo peoples; Kongo Kingdom, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Republic of the Congo, or Angola. Brass (partially hollow cast); H. 4 in. (10.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Ernst Anspach, 1999 (1999.295.1). Photographs by Peter Zeray

Why would Saint Anthony of Padua—a saint who was not crucified—appear on a cross? This likely has to do with a specific aspect of Kongo Christianity, the Antoniens. The followers of this eighteenth-century cult were led by Dona Beatriz Kimpa Vita, who believed she was the reincarnation of Saint Anthony. To the dismay of European missionaries, the Antoniens traveled throughout the Kongo Kingdom wearing medallions of the saint, spreading Dona Beatriz's message of an Africanized church. Threatened by her power and heretical teachings, the church and government combined forces to burn her at the stake in 1706. Despite her death, Saint Anthony remained popular.

Figures of St. Anthony, considered the saint of "good fortune" or "prosperity," continued to be used in Kongo as protection from complications in childbirth or other ailments. The pendants also took on a political role in the nineteenth century, when Kongo chiefs adopted them as insignia of office.

A nail was used to mount this image of Saint Anthony to a wooden shaft, transforming it into a staff finial. Prestige Staff: Saint Anthony of Padua, 19th century. Kongo peoples; Kongo Kingdom. Democratic Republic of the Congo, Republic of the Congo, or Angola. Brass, wood; H. 41 1/2 in. (105.4 cm), W. 2 3/8 in. (6 cm), D. 2 in. (5.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Ernst Anspach, 1999 (1999.295.2). Photographs by Peter Zeray

The staff emphasizes both its owner's Christian beliefs and ties to Kongo history; its iron tip evokes the mythical blacksmith-king who founded the Kongo Kingdom. Today, Saint Anthony remains a major part of Christian worship in the region of the former Kongo Kingdom. He gives his name to the Catholic parish of Santo António, in Luanda, Angola, while Dona Beatriz Kimpa Vita—the self-styled Kongo reincarnation of Saint Anthony—inspires the Kimbanguist Christian church.

Authors' Note

Studies conducted by Conservator Ellen Howe, Conservation Fellow Ainslie Harrison, and Associate Research Scientist Adriana Rizzo, in conjunction with technical analyses performed ten years earlier by Conservator Leslie Gat and Research Scientist Mark Wypski, have determined that the different metal parts that make up Kongo Christian artworks were made at different dates.

This new data has not only dated certain objects with greater precision but has suggested that works were repaired or altered over time. For example, the cross with Saint Anthony spans this entire period: the figure was made between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries, the sheet-metal cruciform inlays were made between the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and the wooden cross itself was made in the nineteenth century.