Raffia palm (Raphia textilis Wilw) from Hélène Loir's Le Tissage du Raphia au Congo Belge

On November 12, Susan Brown, associate curator of textiles at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, sat down with Conservator Christine Giuntini to discuss the materials and techniques Kongo artists used to make the luxury woven textiles in the exhibition Kongo: Power and Majesty, open through January 3.

Fibers and Dyes

A young boy extracting the fibrous inner layer of the palm leaves as a first step in making raffia rope in Bandundu Province, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Image via Wikimedia Commons

Susan Brown: How is raffia processed to create fiber?

Christine Giuntini: Raffia fibers for weaving are harvested from raffia palm, and there are several species. Boys climb up the specifically cultivated trees. They cut off the closed leaf shoot when it gains a certain height. Next, they separate the leaflets from the midrib, and use a knife to strip off the thin green "skin" on each side of the leaflet. The fibers are then left in the sun to dry. The strands, which are of limited length, are then further divided by hand.

In order to create the fine, thin strands needed for weaving textiles, the fibers must be combed. I know of one comb kept in the Royal Museum for Central Africa [Tervuren, Belgium]; it is rare to come across such humble utilitarian objects in museum collections. The prepared fibers are then tied onto a loom and tools are added to the loom to assist the weaver to keep the fibers in the correct order and divide them into the two sets.

Raffia palms are endemic to the Kongo region of Central Africa, and the high-quality weaving developed there was exported to further south, where it was used as currency. Precolonial raffia distribution and trade routes map by Anandaroop Roy, based on a map in Jan Vansina's "Raffia Cloth in West Central Africa, 1500–1800"

Susan Brown: The absence of color in this body of work is rare in the global history of textiles. Do you think there is a technical or cultural reason for the minimal color palette?

Christine Giuntini: In this exhibition, there are only a few raffia pieces to which color has been added. Although the historical sources describe Kongo textiles as brightly colored in shades of red, yellow, and blue, the majority feature their natural color, a deep gold. Your question raises an interesting point, and it is an area for further research.

A sample of undyed, uncombed raffia palm fiber in the Department of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas. Photograph by Kristen Windmuller-Luna

Susan Brown: What was used to create the added colors?

Christine Giuntini: While the colors on these particular pieces have not been analyzed scientifically, historical literature indicates that the colors derive from naturally occurring substances such as minerals found in clay or soil, or colorants from plants.

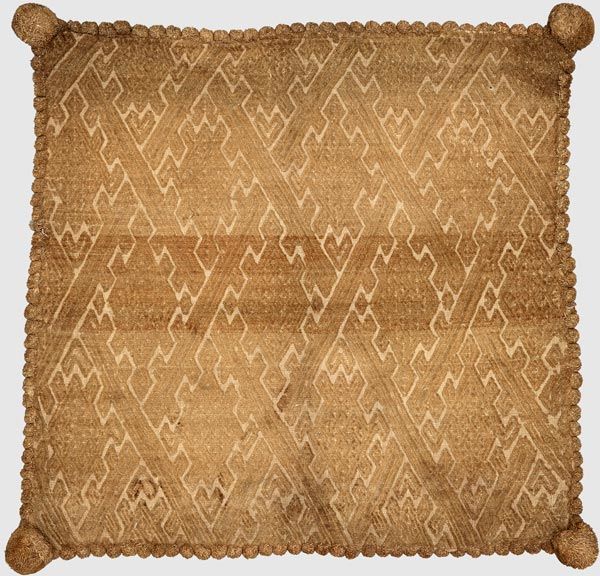

Luxury cloth (detail), 17th–18th century, inventoried 1709. Kongo peoples, Democratic Republic of the Congo; Angola; Republic of the Congo. Raffia, pigments; 43 11/16 x 42 1/8 in. (111 x 107 cm) with fringe, 39 1/8 x 35 7/8 in. (99.5 x 91 cm) excluding fringe. MIBACT – Polo Museale del Lazio, Museo Preistorico Etnografico Luigi Pigorini, Rome (5472)

Susan Brown: So, would the raffia have been dyed, or would the colorants have been applied to the surface after the work was made?

Christine Giuntini: We have evidence of both in the exhibition. The yarns used to embroider the large Pigorini example [shown above] were colored before they were added to the panel. Another example from the Pigorini [shown below] is deeply colored a bluish-black. However, the fibers on the latter example are now degraded, and it is not possible to determine whether the yarns were colored before or after weaving.

Luxury cloth (detail), 16th–17th century, inventoried 1877–1878. Kongo peoples, Democratic Republic of the Congo; Republic of the Congo; Angola. Raffia, black pigment; 16 3/8 x 21 in. (41.6 x 53.4 cm), 16 3/8 x 21 in. (41.6 x 53.3 cm). MIBACT - Polo Museale del Lazio, Museo Preistorico Etnografico Luigi Pigorini, Rome

In addition, there is evidence on at least one of these works that the weaver added in wefts [crosswise threads] of dyed yarn; the color usually appears as a horizontal band or bands. Such bands are found on other cushions, and they are all a reddish color.

Luxury cloth: cushion cover, 17th–18th century, inventoried 1737. Kongo peoples; Kongo Kingdom, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Republic of the Congo, or Angola. Raffia; 21 1/4 x 21 1/4 in. (54 x 54 cm). Nationalmuseet, Copenhagen

Weaving Techniques

Susan Brown: That example is a pile weave, like velvet; can you describe how they were made? How did they raise the wefts to create the pile loops?

Christine Giuntini: Yes, it is a pile weave, and like pile-woven fabrics manufactured around the world, the pile is created by an extra set of fibers or yarns that is added to the foundation weave. In these particular textiles, the foundation weave is a simple, plain-weave structure, where the yarns interlace in an over-one, under-one sequence.

Luxury cloth, 16th–17th century, inventoried 1666. Kongo peoples; Kongo Kingdom, Democratic Republic of the Congo; Angola; Republic of the Congo. Raffia; 19 3/4 in. (50cm) x 22 1/2 in. (57 cm). Nationalmuseet, Copenhagen

Building on the foundational plain weave, the weavers would add a second, supplementary layer row by row by picking up whichever warps they've memorized for that row and placing the supplementary weft bundle—which is considerably thicker—inside.

A close-up of a textile reveals the even size of the loops of uncut pile raised against the background of plain weave. Luxury cloth: cushion cover (detail), 16th–17th century, inventoried 1737. Kongo peoples; Kongo Kingdom, Democratic Republic of the Congo; Angola; Republic of the Congo. Raffia; 23 1/4 in. (59 cm) x 23 1/4 in. (59 cm). Nationalmuseet, Copenhagen

We borrowed one textile from Copenhagen's Nationalmuseet especially because of its unfinished state. It demonstrates how the supplementary weft was raised to form a series of little loops. Historical sources describe the pile as being formed by little "pins." It is quite possible that once a row of the pile weft was secured into place by the warps, the weaver did use tiny slivers of wood to form and hold the tiny, uniformly sized loops in position, most likely starting from the middle and working toward each of the sides.

A close-up of foundation plain weave (1), uncut bundles of fiber (2), and cut and brushed pile (3) on a luxury cloth

Susan Brown: How were the different levels of pattern and texture created?

Christine Giuntini: In some of these textiles, the very light-toned weave surrounding the crenellations are completely voided areas where all of the supplementary weft is cut out and you're just seeing the foundation plain weave. The uncut, supplementary weft bundles are used to create a ribbed effect. Uncut bundles reflect light differently from the pile. Together the three levels give depth to the design.

Susan Brown: We clearly see transmission of visual elements from one culture to another, but technology is more entrenched. Did Kongo weavers ever incorporate European materials or other materials besides raffia into their weaving?

Christine Giuntini: To date, there is no evidence that any of the surviving sixty-five or so of these presentation cloths and cushions incorporates any material other than raffia palm fiber.

Shapes and Patterns of Kongo Textiles

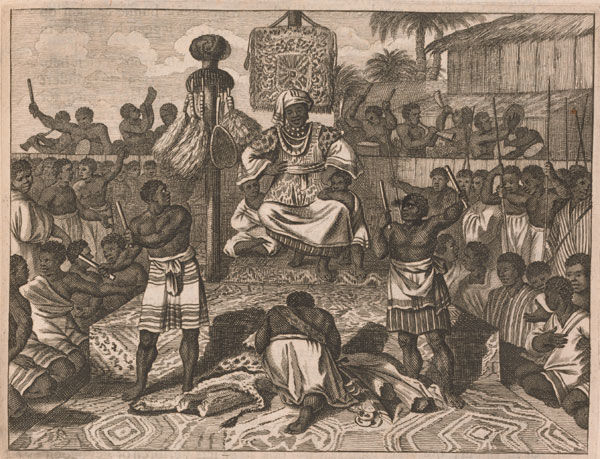

Depictions of the diverse forms and uses of woven textiles in Kongo and the nearby kingdom of Loango survive only in illustrations. Olfert Dapper (Dutch, 1635–1689). King of Loango (Maloango) engraving from O[lfert] Dapper, Naukeurige Beschrijvinge (Amsterdam), p. 539, 1686. H. 14 9/16 x W. 9 13/16 x D. 2 9/16 in. (37 x 25 x 6.5 cm). Library Gigi Pezzoli, Milan

Susan Brown: Cushion covers, as I understand, were made as diplomatic gifts for European dignitaries. Why did the Met focus its selection of pile-woven textiles on these, and not the luxury cloths that Kongo elites kept as a form of wealth?

Christine Giuntini: When the Portuguese first arrived, in 1483, as merchant-explorers eager for trade, I do not think they had the mindset of collecting. What survived was brought back to Europe during subsequent visits. After the King of Kongo had declared his Christianity [in 1491], he sent back diplomatic gifts to European princes, perhaps in return for gifts sent from Europe. That is why these early works all appear to be presentation pieces [sewn into cushion format] rather than pieces of cloth.

Unfortunately, nothing survives of the opulent Kongo clothing that the historic sources describe. Based on knowledge of raffia weaving that existed in the nineteenth century, we presume that Kongo artists sewed individual raffia cloth panels together to tailor clothing for the elites.

Bartolomeo Vivarini (Italian, 1450–91). The Madonna of Humility, the Annunciation, the Nativity, and the Pietà (details), ca. 1465. Tempera and gold on wood; Central panel: overall 23 x 18 in. (58.4 x 45.7 cm), left panel: overall 22 3/8 x 9 1/2 in. (56.8 x 24.1 cm), right panel: overall 22 1/4 x 9 3/8 in. (56.5 x 23.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Robert Lehman Collection, 1975 (1975.1.82)

Susan Brown: Did Kongo weavers see examples of European tasseled cushions and decide to try out a new form, or did Europeans commission a familiar form in new materials?

Christine Giuntini: We know the cushion format is a Eurasian development of great antiquity, however, we do not know from which direction the influence came. Missionaries and travelers who worked in this hot, humid region described in vivid detail the varieties of insects that sting or carry disease. It's hard to image that a cushion—something that's filled with fibers, where you couldn't really see what was inside of it—was really popular in these climates. Mats and neck rests were more prevalent, as a response to the particular climate.

I believe the Kongo cushion format was based European prototypes that African weavers then took apart to understand how they were made. This square or oblong type, with the perimeter seams embellished with pompoms and the corners embellished with tassels, is found in a variety of paintings, prints, and drawings from the fifteenth through late sixteenth centuries. Unlike indigenous Central African raffia garments and panels, where the finished edges are generally turned to the face of the cloth, these raffia panels that were made into cushions that had all their edges neatly trimmed and folded toward the back [or inside] in the European manner.

Susan Brown: Is there any way to know where the design impetus came from?

Christine Giuntini: We can't know for sure, but if we compare the cushion patterns to those on the ivory carvings, the patterns are very similar. This format of an endless, interlaced network is likely indigenous. Across the globe, interlace patterns seem to have spontaneously developed as a decorative motif. In many of the Kongo textiles on view in the exhibition, the interlace patterns are deconstructed, creating an uneven rhythmic repetition that spreads out "forever" in all directions. It is a pattern without end, so to speak.

Oliphant, 16th century, inventoried 1553. Kongo peoples, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kongo Kingdom; Republic of the Congo; Angola Culture: Kongo peoples. Ivory, L. 32 3/4 in. (83.2 cm). Palazzo Pitti, Museo degli Argenti, Florence (Bg. 1879 avori, no. 2)

Susan Brown: Interlace patterns are so dominant here. Do they have some cosmological significance in the local pre-Christian belief system?

Christine Giuntini: If they did, it has been lost to history. However, when anthropologists and historians asked questions about the significance of the designs during the nineteenth century, similar patterns did have meaning. So, it is possible that the patterns had significance three hundred years before.

A variety of interlace patterns used on a single textile. Luxury cloth (detail), 16th–17th century, inventoried 1659. Kongo peoples; Kongo Kingdom, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Republic of the Congo, or Angola. Raffia; L. 75 9/16 in. (192 cm), H. 59 7/16 in (151 cm), excluding 5 1/2 in (14 cm) perimenter fringe. Kunst- und Wunderkammer des Christoph Weickmann, Ulmer Museum, Ulm, Germany

Susan Brown: Did they use a pattern, as in tapestry weaving, or work without a pattern and memorize a sequence?

Christine Giuntini: We do not know how patterns were passed on from one weaver to the next, but it is most likely that weavers—who were male in the Kongo region—were trained from a young age to memorize these complex, repeating patterns. Just as musicians have memorized the music played by their fingers, weavers in traditional cultures have what is sometimes called muscle memory.

To think of the mathematical concentration of their minds and the years of learning that must have gone into creating such elaborate patterns can boggle our minds, and it is easy to understand that when the Kongo city-state was disrupted by political unrest, all this highly technical information would've been lost.

Editors' note: This interview was facilitated and transcribed by Graduate Intern Helina Gebremedhen, and edited and condensed from the original by Kristen Windmuller-Luna, Sylvan C. Coleman and Pamela Coleman Memorial Fund Fellow.