The first gallery in Kongo: Power and Majesty. The ivory oliphant at left and limestone padrão at right served as the starting point for the exhibition design. Photograph by Peter Zeray

Two striking works greet visitors as they enter the exhibition Kongo: Power and Majesty, on view through January 3, 2016. To the left, seeming to float in its case, is an exquisitely carved ivory oliphant sent as a diplomatic gift by King Afonso I of Kongo to Pope Leo X. To the right is a roughly contemporaneous work: a tall limestone column, or padrão, originally positioned south of Benguela in modern-day Angola by Portuguese navigator Diogo Cão in 1483.

These two works served as the starting point for the exhibition's stunning design, which was developed over the course of nearly a year by the Met's Senior Exhibition Designer Brian Butterfield and Senior Graphic Designer Yen-Wei Liu.

Both designers were aware of these objects' importance from the outset of the design process. "[Curator] Alisa LaGamma had identified [these works] from the beginning as being the DNA of the show," Butterfield noted. "They set up the narrative, emblematic of the historic relationship between Kongo and outside powers. They represent a dialogue of cultural exchange and trade that continues from this point for over five hundred years."

Yen-Wei Liu, left, and Brian Butterfield at the entrance to Kongo: Power and Majesty, the exhibition for which they developed the physical design and visual identity over the course of nearly a year. Photograph by Helina Gebremedhen

The designers took a largely chronological approach to organize the 146 objects featured in the exhibition, with signature works acting as leads in each gallery. "We wanted to create a sense of hierarchy," said Butterfield. "We didn't want the exhibition to feel like a checklist; it's an exhibition of ideas, with artworks from different times and geographic regions responding to different political moments, and we wanted there to be a correlating spatial effect that gives that impression on a subconscious level."

Left: View of gallery 1 under construction. Photograph by Helina Gebremedhen. Right: The finished gallery. The textile display is one example of the designers' attention to spatial effect; angled wall cases allow the visitor to view the rich detail of the works and draw comparisons and connections between them. Photograph by Peter Zeray

The design of the individual object cases was a way to leave subtle hints for the visitor. Cutouts in the walls between gallery spaces were "intended as a foreshadowing device, allowing the visitor a sneak peek through to the final, dramatic gallery of fifteen Mangaaka power figures," explained Butterfield. "It doesn't ruin the impact of the final gallery, but it prompts visitors to zoom in and out a little in terms of the scale of their attention."

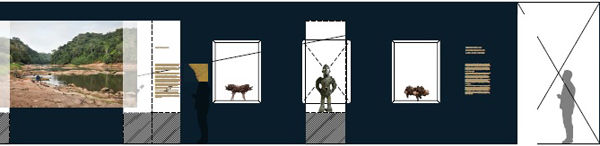

Gallery drawing used in planning the exhibition design. The window-like object cases at center allow visitors to peek into the next gallery. Image courtesy of Brian Butterfield and Yen-Wei Liu

Yen-Wei Liu worked to develop a clear visual identity for the exhibition—an important element since the media and marketing materials associated with an exhibition serve as its public face. "It's a complex process," he said. "To create an exhibition identity, you need to adopt some sort of stance. You cannot cover everything; if you try to talk about everything, you end up talking about nothing, and so you just have to choose an element that is most representative."

So how does one convey abstract themes like "power" and "majesty"? "As a designer, as a visual person, there are a lot of solutions," said Liu. "For me, I wanted to create a graphic that is interesting and meaningful in a way that doesn't just visually mimic what the object does, but represents that kind of attitude, evokes it, through graphics."

Yen-Wei Liu designed the typographic treatment of the exhibition title, visible in the upper left-hand corner of the introductory wall text, as well as on a range of media and marketing materials associated with the exhibition. Photograph by Peter Zeray

Pattern elements—such as the diamond shapes woven into the textiles, carved onto the backs of figures, and found on ceramic fragments—were a huge inspiration for Liu.

Top: View of seated female figures in Gallery 4. Photograph by Peter Zeray. Bottom left: Luxury cloth (detail), 16th–17th century, inventoried 1659. Kongo peoples; Kongo Kingdom, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Republic of the Congo, or Angola. Raffia; L. 75 9/16 in. (192 cm), H. 59 7/16 in (151 cm). Kunst- und Wunderkammer des Christoph Weickmann, Ulmer Museum, Ulm, Germany. Bottom right: Figure: Seated female supporting figure with clasped hands (detail), 19th century, inventoried 1898. Kongo peoples; Yombe group. Democratic Republic of the Congo, Republic of the Congo, or Cabinda, Angola. Wood, metal, glass, kaolin, pigment; H. 10 7/8 in. (27.5 cm), W. 4 1/2 in. (11.4 cm), D. 4 5/8 in. (11.7 cm). Ross Art Management, LLC, New York

He was also inspired by the pose of several of the figures: "I was also thinking about how all the [Mangaaka] power figures have the same pose, with the arms on the hips—a gesture of making themselves seemingly larger in physique. It's almost like a person trying to create that diamond shape with the body," he said.

The exhibition's final gallery, which brings together fifteen of the twenty known surviving examples of nkisi n'kondi Mangaaka figures, is the exhibition's visually striking, dramatic finale. The grouping has drawn comparisons to a battalion, an army, or a legion, and these military references are apt; the power figures were created to defend their communities against incursions into the region by various European powers in the mid- to late nineteenth century.

Mangaaka power figures in Gallery 5. Photograph by Peter Zeray

The figures' presentation in ten-foot-tall cases, set at a 45-degree angle, emphasizes the role they played in Kongo communities as defensive mechanisms. According to Butterfield: "By rotating all of the figures to be able to face you head on as you turn the corner, we're playing up the dramatic nature that these objects were supposed to be imbued with. Furthermore, the diagonal grid arrangement evokes the patterning seen on the textiles and oliphants—getting back to this idea of the DNA of the show."

Brilliantly vivid, contemporary photographs of the riverine landscapes where these figures were produced, and historical images of the Chiloango River, give the visitor a sense of place, while also tempering the systematic idea of a Mangaaka "army," reminding the visitor that these works would have been seen individually.

Hector Gibson Fleming (British, b. 1987). Kouilou River south of Kakamoeka, Republic of the Congo, September 2012. Photograph courtesy of the artist

"The design of this room is meant to give you a sense of the imposing nature of these objects," said Butterfield. "We obviously can't put them in the actual landscapes…but we can try to create a gallery environment that at least has something of a similar effect in terms of magnitude."

Liu agreed. "We had this idea of doing a slideshow, a large moving graphic that creates a sense of narrative within the slides themselves. It tells the story of these figures' original environment, but also, at certain moments with the historical images, you see the commercial ports these works were shipped from."

The goal of the exhibition design, admitted Butterfield, was to throw off the visitor a little bit. "This [final] gallery isn't necessarily about a close view, about understanding each object individually," he explained. "The scholarly elements are all there, but by creating these moments of 'confusion,' for lack of a better term, we make you stop, turn, and contemplate the works from a different perspective. It takes a minute to sort out what you are looking at—it's a layered experience."