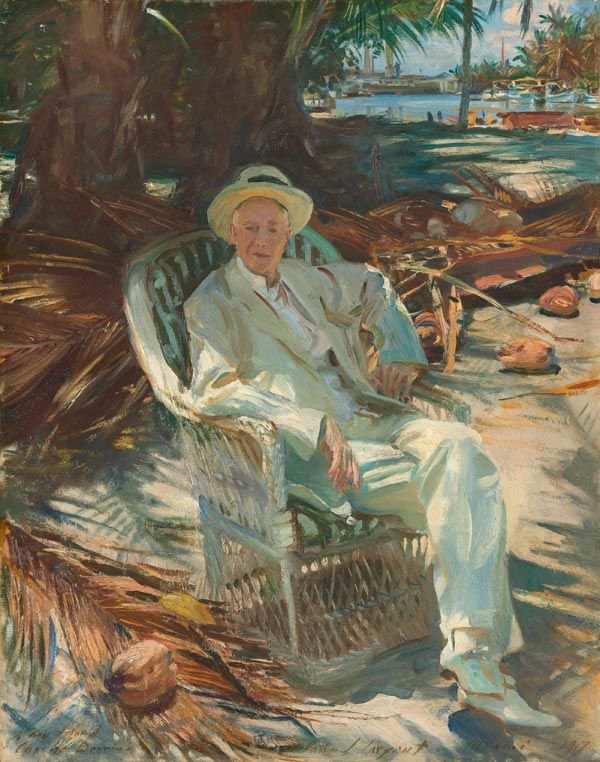

John Singer Sargent (American, 1856–1925). Portrait of Charles Deering, 1917. Oil on canvas; 28 1/2 x 21 in. (72.4 x 53.3 cm). Private collection, Chicago

I first encountered John Singer Sargent's portrait of Charles Deering in 1999 while visiting the home of a distinguished collector. I had been ushered into the dining room, where my eyes went immediately to the dazzling image of the older man, lithe and relaxed, lounging in a wicker chair in a lush, tropical setting. While I had never seen the portrait, I recognized Sargent's work immediately. The artist's delight in rendering light and shadow across the sitter's crinkled white suit recalls the splendid textiles of formal portraits such as Ada Rehan. The setting—painted in a bright palette and fluid style—echoes Sargent's watercolor technique and relates to several works in the Met's collection also painted during his visit to Florida in 1917. Currently on view in Sargent: Portraits of Artists and Friends, the painter's image of Deering seamlessly blends aspects of portraiture and landscape painting to create a unique and candid masterpiece.

At the time I was deeply immersed in a massive project—cataloguing the Met's more than three hundred drawings and watercolors by Sargent. I was also researching Sargent's portrait of Mrs. Hugh Hammersley, which had been owned by Charles Deering (1852–1927) from 1923 until his death, and was later gifted to the Met in 1998. I was just learning about Deering and his life as an amateur artist, an important collector and patron of the arts, and a lifelong friend of Sargent. I was fascinated by the connection between Deering and the portrait of Hammersley.

John Singer Sargent (American, 1856–1925). Mrs. Hugh Hammersley, 1892. Oil on canvas; 81 x 45 1/2 in. (205.7 x 115.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Douglass Campbell, in memory of Mrs. Richard E. Danielson, 1998 (1998.365)

Sargent had met Deering at Newport, Rhode Island, in 1876, during his first-ever trip to the United States. Deering was married to Annie Case, the daughter of Sargent family friends. That summer, Sargent commemorated the meeting by painting a portrait of Deering (currently held in a private collection, location unknown), who was then in the United States Navy, wearing his uniform. Sargent later painted a posthumous portrait of Deering's wife Annie (also in a private collection, location unknown), who had died in childbirth. After leaving the Navy, in 1881, Deering became an extremely successful businessman, serving as the chairman of the machinery company that would become International Harvester Corporation. In 1883, he married Marion Denison Whipple, and the couple later had three children.

Deering was passionate about art and studied painting in Paris for a year. He was a devoted Hispanist and owned a castle in Sitges, Spain, south of Barcelona. He amassed an impressive collection of art by both old and contemporary masters for his homes in Spain and the United States, eventually owning more than a dozen works by Sargent. His family became important patrons of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Sargent's portrait of Deering, painted in Florida forty-one years after the two men first met, seems to reflect the comfortable familiarity of longtime friends. Sargent had traveled to Florida to work on a portrait of John D. Rockefeller. While there, he visited Deering at his home at Brickell Point, Miami, and painted this portrait. Inscribed "to my friend/Charles Deering," Sargent probably presented the painting to his friend as a token of gratitude for hosting him. Sargent also visited Charles's half-brother, James, whose elaborate Italianate villa, Vizcaya, was then under construction a few miles away. Sargent wrote to his cousin: "There is so much to paint . . . at my host's brother's villa. It combines Venice and Frascati and Aranjuez, and all that one is likely never to see again. Hence this linger-longing." For Sargent, Vizcaya conjured memories of his favorite painting sites in Europe, which were then inaccessible because of World War I.

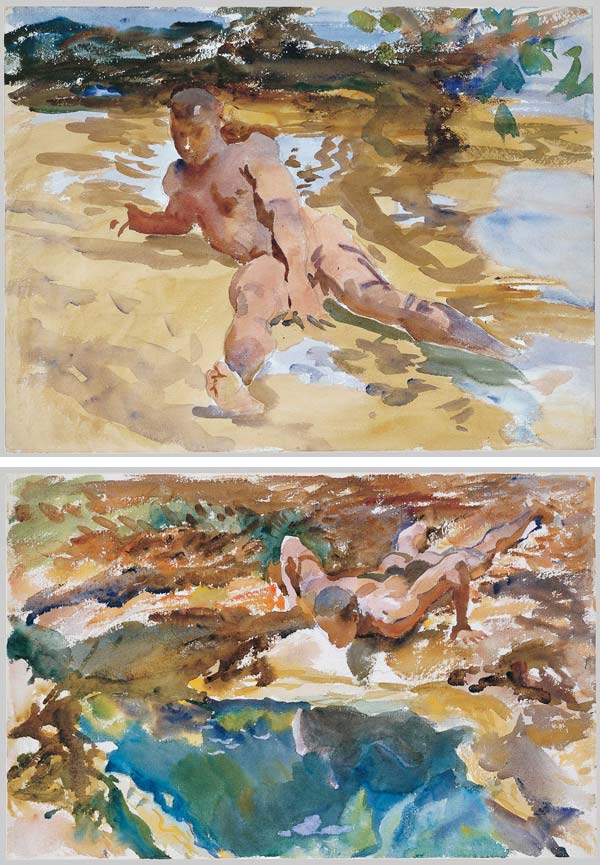

Sargent sold an assortment of his Florida watercolors to the Worcester Art Museum while keeping a selection of more candid, experimental, and unfinished works in his personal collection. Ten of these works came to the Metropolitan Museum with the remains of Sargent's estate, in 1950, three of which are currently on view in the exhibition's reading room. In this dazzling series, Sargent used the muscular laborers who were then constructing Vizcaya's garden as his models. He posed them in the preserved natural landscape on the property, combining his sensuous delight in rendering the male nude figure with his favorite watercolor themes of sunlight and water.

Top: John Singer Sargent (American, 1856–1925). Man on Beach, Florida, 1917. Watercolor and graphite on white wove paper; 15 3/4 x 20 7/8 in. (40 x 53 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Francis Ormond, 1950 (50.130.61). Bottom: John Singer Sargent (American, 1856–1925). Man and Pool, Florida, 1917. Watercolor and graphite on white wove paper; 13 11/16 x 21 in. (34.8 x 53.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Francis Ormond, 1950 (50.130.62)

Deering was determined to add formal portraits by Sargent to his growing collection and began seeking works on the secondary art market. In 1923, he purchased Sargent's portrait of Mrs. Hugh Hammersley. Painted in London, in 1893, Mrs. Hammersley was, like Deering, a significant patron of the arts who became one of Sargent's close friends. Hugh Hammersley was struggling financially and sent the portrait to the Carnegie Institute in Pittsburgh in the hopes of attracting a buyer.

It's not a coincidence that Mrs. Hammersley was being shown at the Carnegie Institute. As Thayer Tolles previously wrote on this blog, Homer Saint Gaudens, whom Sargent had painted in 1890, grew up to become, in 1922, the director of that museum. Sargent had called upon Saint Gaudens to help sell Mrs. Hugh Hammersley. The purchase was reported in the Art News in November 1923, and though the article didn't mention Deering, it noted that "The purchaser is a well-known American collector who is anxious that the best works of the great American portrait painter should remain in this country." Mrs. Hugh Hammersley descended in the Deering family until it was presented to the Met, in 1998, as a gift in honor of Mrs. Richard Danielson (Deering's daughter) from Mr. and Mrs. Douglass Campbell (Deering's granddaughter and her husband).

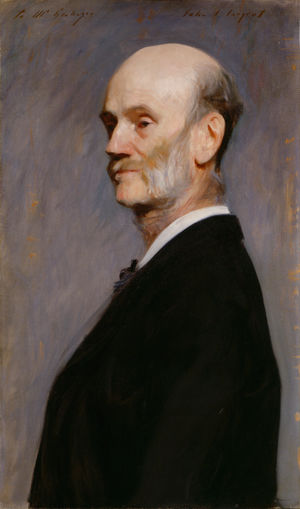

Left: John Singer Sargent (American, 1856–1925). Hercules Brabazon Brabazon, 1893–95. Oil on canvas; 28 7/8 × 17 in. (73.3 × 43.2 cm). National Portrait Gallery, London

Left: John Singer Sargent (American, 1856–1925). Hercules Brabazon Brabazon, 1893–95. Oil on canvas; 28 7/8 × 17 in. (73.3 × 43.2 cm). National Portrait Gallery, London

In Sargent: Portraits of Artists and Friends, we are pleased to reunite the portraits of Charles Deering and Mrs. Hugh Hammersley with a third work once owned by Deering: Hercules Brabazon Brabazon. We have described Sargent: Portraits of Artists and Friends as an exhibition about the artist's relationships with his sitters, but I hope that this post begins to suggest the complexity of these connections between the artist, his sitters, and his patrons. Sargent cherished and maintained these connections throughout his life: they inspired his creativity and helped to insure his artistic legacy.

Do you feel a special connection to a portrait in the exhibition—either an old favorite or a new discovery? I'd love to hear about it in the comments section.

Sources

Ormond, Richard, and Elaine Kilmurray. John Singer Sargent: Complete Paintings, vol. III (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2003), 242.

"Carnegie Sells Two Sargents for $60,000." In The Art News XXII (November 10, 1923): 1.