Cubism and the Trompe l’Oeil Tradition

Visiting Guide

Prelude

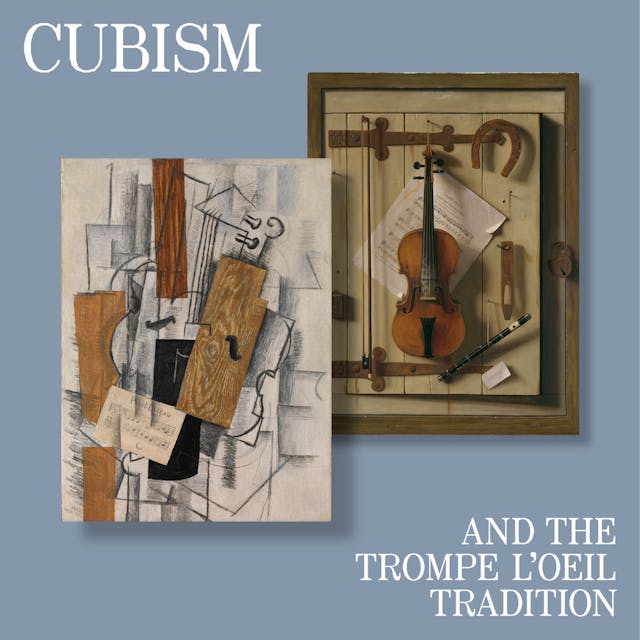

One of the oldest forms of Western painting, trompe l’oeil (French for “deceive the eye”) would seem to have little in common with the anti-illusionism of the Cubists; this exhibition reveals otherwise. A self-referential art that calls attention to its own artifice, trompe l’oeil, like Cubism, involves the viewer in perceptual and psychological games that complicate definitions of reality and authenticity.

Trompe l’oeil easel painting flourished in mid-seventeenth century Europe, inspired by Pliny the Elder’s legendary account of how a painted image could be taken for the real thing—at least momentarily. Typically, artists augmented their “counterfeits” by including painted simulations of handwritten texts and printed matter, blurring the boundaries between the private and the public spheres, fine art and popular culture. Frequently disparaged as mere copyists, they showed off their ingenuity with unexpected sleights of hand and elevated the humble genre of still life with commentary on contemporary affairs and morality.

The reputation of trompe l’oeil painting declined precipitously during the nineteenth century, which may explain why its connections to Cubism have been largely overlooked. Yet Georges Braque, Juan Gris, and Pablo Picasso similarly laid bare the conventions of verbal and visual representation, filled their pictures with allusions to art and art making, and upended hierarchies of taste. They parodied and emulated trompe l’oeil strategies in a three-way contest of creative one-upmanship that accelerated with the introduction of collage techniques in 1912. The presence of actual things in the picture—newspaper clippings and illusionistic wallpapers—resulted in previously unimaginable levels of paradox and new ways of confounding the mind. Like the trompe l’oeil artists of earlier centuries, the Cubists raised provocative questions about originality, truth, and falsehood that remain relevant today.

Selected Artworks

View allOrigin Stories

The main types of trompe l’oeil painting originated during the Baroque period, notably letter-rack and board pictures. These compositions refuse spatial recession and feature assorted objects projecting from a solid background plane. Artists introduced fake frames, pictures-within-pictures, and other devices to alert the viewer to the clever deceptions at work. Trompe l’oeil enjoyed a resurgence in the United States during the 1890s, with novel conceits inspired by advertising and the con games played in bars and streets during the commerce-driven Gilded Age. The Cubists reinvigorated hackneyed tropes, redefining artistic skill and ingenuity in an era when photography and cinema had eclipsed painted illusion. Braque, who had trained as a painter-decorator, was the first to experiment with trompe l’oeil motifs and faux woodgrain surfaces, introducing illusionistic details into his nearly abstract compositions. In spring 1912, Picasso made the radical move of pasting an actual fragment of material reality into a still life, transgressing the virtual threshold of painting. Gris trumped both artists that autumn when he unveiled the new art of Cubist collage to the Parisian public, using a version of the pulled back curtain (reproduced here) from Pliny’s the Elder’s famous story of artistic competition.

Selected Artworks

View allThings on a Wall

Objects, papers, prints, and drawings nailed or strapped to a hard, flat surface were a favorite theme of trompe l’oeil painters. Typically, the surface simulates wood in all its peculiarities of grain, knot, and split, and the things set upon it seem to push beyond the picture plane into the spectator’s space with a heightened presence. Stories abound of people reaching out to verify by touch and reacting with astonishment and pleasure on discovering the deception.

A violin or guitar suspended against a wall, sometimes accompanied by sheet music, a drawing, or a print likewise joined the Cubists’ artistic repertory. Not coincidentally, Braque and Picasso displayed their musical instruments in this manner and hung their pipes over a strap nailed to the wall. In 1912, when the Cubists’ expanded their range of novel techniques to include collage, papier collé (pasted paper), and mixing sand in oil paint, tactility as such became increasingly important to them. The different weights and types of paper and other materials they used to build their compositions resulted in actual, if slight, relief. In their hands, tangible reality replaced the pure illusionism of trompe l’oeil painting.

Selected Artworks

View allTrompe l’Oeil and the Artisanal Tradition

Despised by academic critics, who claimed it required mere manual skill, trompe l’oeil easel painting declined during the nineteenth century. In France, however, peintres décorateurs (painter-decorators) kept the tradition alive. They were responsible for the convincing imitations of wood, marble, stone, and architectural features encountered in every type of building, and for the illusionistic imagery and ornate signage that adorned shops and businesses. In reviving trompe l‘oeil techniques, the Cubists intentionally subverted fine-art traditions by imitating the methods of artisans.

Braque’s grandfather and father were peintres en bâtiment (housepainters). In later life the artist paid tribute to his artisanal training, received in the family firm in Le Havre and from peintres décorateurs who taught him how to achieve trompe l’oeil effects. Braque never practiced the trade professionally, but in 1911–12 he began introducing lettering and passages of faux bois (imitation wood) in his Cubist paintings. He showed Picasso how to use decorators’ graining combs and taught him tricks of the trade, such as mixing sand in paint to simulate a stony surface. When he incorporated wallpaper in his drawings in autumn 1912, he invented the technique of papier collé (pasted paper). Critics in the Cubists’ circle hailed Braque’s leadership in this radical move to invigorate art through craft practice.

Selected Artworks

View allThings on a Table

For deception to occur, albeit fleetingly, the objects in a painting must be life-size and fully within the picture. A receding table that exceeds the boundaries of the painted surface, as in a traditional still-life composition, does not obey the rules of the trompe l’oeil game. Careless of such fine distinctions, the Cubists frequently chose to merge two conventions: the tabletop still life and the trompe l’oeil board or letter-rack painting. They set their objects on a table—recognizable as such from its legs, drawer with knob, and carved edge—but depicted its top tipped up almost vertically, parallel to the picture plane, denying spatial recession.

From the moment still life emerged as an independent genre in the 1600s, pure description was seldom the artist’s sole concern. Objects were chosen to not only display painterly virtuosity and appeal to the senses but also suggest a way of life. Frequently, they point to a moral about the human condition, such as the vanitas (Latin for “vanity”) message that all earthly things are transient and death is inevitable. The Cubists embraced these aspects of the still-life tradition, often inserting scraps of text to encourage an imaginative response to the imagery.

Selected Artworks

View allShadow Play

Light and shadow shape our perceptions of the world. Highlights and shading create volume, texture, and depth, and they make tactile the relative thickness and thinness of things. A cast shadow is a potent sign for something real, caused by an object that blocks the light and whose shape it mimics in silhouette when thrown upon an adjacent surface. Trompe l’oeil shadows give visual coherence to painted illusions but also account for the hyperreal presence of objects.

Artists over the centuries enlisted shadows to deceive and to undeceive the eye. A prime example is the ubiquitous nail, whose silhouette creates the perception of a fictive third dimension while also pointing to the material reality of the flat canvas. The Cubists elaborated upon these conceits, foregrounding the magic of chiaroscuro, which normally escapes our attention, through exaggerated crosshatching and sfumatura (blending), as well as illogical reversals of light and dark. In 1913 they went further: Picasso pasted and pinned some of his paper cutouts so that they lift slightly off the surface, casting real shadows from within the picture; Gris broke with the Western pictorial tradition by representing objects only in black silhouette, heightening the innately theatrical element of trompe l’oeil with humorous and uncanny twists.

Selected Artworks

View allParagone

The term paragone (Italian for “comparison”) refers to debates conducted during and after the Renaissance about which art form could best “imitate nature,” painting or sculpture. Although Cubism was defiantly not imitative, in using novel collage and construction techniques, Picasso made the case for hybrid modes of expression and explored the potential for creative exchanges between these supposed rivals. Still life was traditionally considered too lowly a subject for the art of sculpture and suited only to painting. Picasso challenged this assumption, and the sculptures he constructed in 1912–15 are tabletop still lifes that often parody trompe l’oeil devices. Nearly all are reliefs—the type of sculpture closest to painting. The papiers collés displayed in this room explore the same subject matter as Picasso’s constructions: always involving a built-up surface, these collages mediate between his two-dimensional paintings and three-dimensional reliefs. He gave color and pattern as vital a role in his sculpture as in his painting, sometimes simulating materials he never used (notably marble) and playfully juxtaposing hand-painted shadows with real ones cast by projecting elements. Deceiving, perplexing, and thereby stimulating the intellect—moving beyond trompe l’oeil to trompe l’esprit, “fool the mind”—was a key Cubist goal.

Selected Artworks

View allThe World of Wallpaper

Wallpaper, described by an historian in 1914 as “the supreme art of counterfeit,” was the Cubists’ handy source of ready-made trompe l’oeil effects. Drawing on his artisanal training, Braque was the first to incorporate wallpaper in his drawings, thereby inventing the papier collé (pasted paper) technique in September 1912. Picasso followed suit a few months later, and Gris in early 1913. Rather than using the luxury hand-printed papers for which France was universally renowned, they identified with consumers of meager means by choosing inexpensive, widely available, machine-printed products that imitated natural and manufactured materials used in interior decoration.

Many patterns and styles came freighted with conventional social and gendered associations; the Cubists exploited these to evoke a particular environment or situation. Braque and Gris usually chose papers in current production, notably wood and marble patterns that were the cheap alternative to imitations of the real thing executed by professional decorators. But Picasso went out of his way to obtain obsolete nineteenth-century papers redolent of another era. In attaching their cuttings, all three disregarded the correct orientation of the designs whenever it suited them to do so. All three artists also became adept at mimicking wallpaper in their paintings.

Selected Artworks

View allThe Typography of Trompe l’Oeil

Play with word and image was a staple of trompe l’oeil. Book pages, paper currency, pamphlets and flyers, mastheads and headlines, advertising copy and labels—over the centuries the varieties of printed matter and typefaces increased exponentially, but the strategy remained the same. When artists reproduced texts, they often surreptitiously fiddled with the contents, cueing the viewer to read carefully and not take things at face value. Likewise, the Cubists painted or pasted in typographic snippets to pun, allude, opine, or self-advertise. Titles and headlines carry coded messages, brim with innuendo, and exploit the slippages between literal and figurative language.

From the late seventeenth century onward, newspapers appear in trompe l’oeil letter-rack and board paintings, making the press reports as suspect as the pictures themselves. Keeping with the self-reflexive theme, the stories often mention false appearances, deceptive practices, or audience gullibility, while boldface mastheads and choice phrases underscore the act of communicating here and now with the viewer. As with the clippings in Cubist collage, references to war and human folly generate tension between wit and tragedy. All told, the miscellany of fragmentary texts stimulates the beholder to piece together—even invent—meaning, revivifying faded newsprint and forgotten events.

Selected Artworks

View allPapyrophilia

A love of papers (papyrophilia)—and the variety of visual conundrums they enable—links the Cubists and trompe l’oeil painters. Flat to begin with, papers can trick the eye more readily than painted objects with depth. Beginning in the eighteenth century, compositions known as “messy tables” and “medley images” mimicked the look and feel of various prints, drawings, and ephemera strewn across a surface. Littered with allusions, these compositions demand a dual reading, toggling between horizontal and vertical, the virtual view down upon a table and the actual appraisal of a picture hanging on a wall.

The Cubists likewise conflated the table with the tableau (“picture” in French), though they combined represented and real papers. In both art forms, deft shading around the papery planes creates fictive depth on top of the surface, while drawing attention to the picture’s inescapable flatness of being. Gris and Picasso typically tilted up their tabletops, playing with the relationship between the table edge and that of the picture. In a series of works from 1913–14, using his signature wood-grain papers and other printed matter, Braque engaged in a more knowing cut up of the “messy table” tradition.

Selected Artworks

View allThe Artist is Present

A trompe l’oeil image must hide the hand of its maker. A distinctive style, visible brushwork, or free-floating signature would disturb the illusion. Instead, artists asserted their presence through symbolic devices, versions of their own artworks, and autographs “engraved,” “carved,” or otherwise embedded into still-life objects. Painters included references to their inner circle of patrons, artists, and writers, in a form of name-dropping that added luster to their own reputations. The insertion of written testaments or mentions in the press (real or fake) added yet another level of self-promotion. Through this simultaneous concealment and performance of the self, they flaunted their inventiveness.

The Cubists’ ironic play with conventional signs of authorship—especially in collages that seemingly defy the artistry of the hand-rendered image—came out of this long tradition. They invented irreverent versions of the nameplate and other forms of fake signatures that nonetheless function as “authentic” autographs. Braque, Gris, and Picasso delighted in testing assumptions about art and reality. They transformed humble still lifes made with mass-produced materials into works of singular ingenuity, often tricking the unsuspecting viewer with passages of traditional visual deception. As in trompe l’oeil, it is wit, or jeu d’esprit, that prevails.