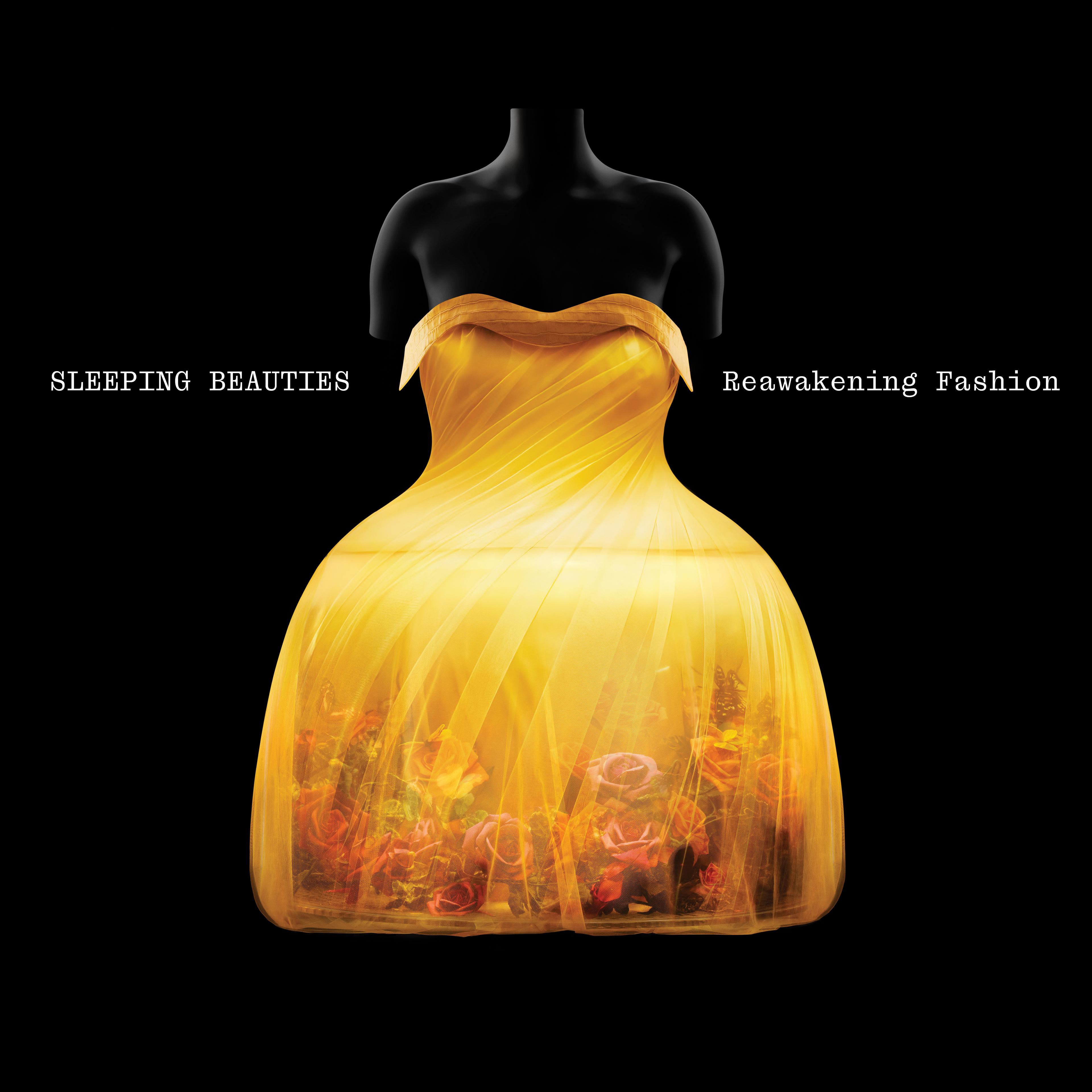

Introduction

When an item of clothing enters The Costume Institute’s collection, its status is irrevocably changed. What was once a vital part of a person’s lived experience becomes a lifeless work of art that can no longer be worn, heard, touched, or smelled. Sleeping Beauties: Reawakening Fashion endeavors to resuscitate garments from the collection by reactivating their sensory qualities and reengaging our sensorial perceptions. With its cross-sensory offerings, the exhibition aims to extend the interpretation of fashion within museums from the merely visual to the multisensory and participatory, encouraging personal connections.

The galleries unfold as a series of case studies united by the theme of nature. Motifs such as flowers and foliage, birds and insects, and fish and shells are organized into three groupings: earth, air, and water, respectively. In many ways, nature serves as the ultimate metaphor for fashion—its rebirth, renewal, and cyclicity as well as its transience, ephemerality, and evanescence. The latter qualities are evident in the “sleeping beauties,” garments that are self-destructing due to inherent weaknesses and the inevitable passage of time, which ground several of the case studies.

Sleep is an essential salve for a garment’s well-being and survival, but as in life, it requires a suspension of the senses that equivocates between life and death. The exhibition is a reminder that the featured fashions—despite being destined for an eternal slumber safely within the museum’s walls—do not forget their sensory histories. Indeed, these histories are embedded within the very fibers of their being, and simply require reactivation through the mind and body, heart and soul of those willing to dream and imagine.

Painted Flowers

Floral imagery was the most popular source of patterning for dress in the eighteenth century, exemplified by the two hand-painted silk gowns in this gallery. Both reveal the era’s penchant for Orientalism: the 1780s robe à l’anglaise is made from silk woven and painted in China for export to Europe, while the 1740s robe à la française is of European manufacture in imitation of Chinese export silks. In addition to the stylistic differences in the depiction of the flowers—the former’s are delicate and naturalistic, the latter’s large-scale and fantastical—there are also technical variances: Chinese export silks are typically underpainted in lead white and outlined in black paint, both of which are absent in the robe à la française.

Orientalism remained popular in the nineteenth century, as evidenced by the reception gown by Mme Martin Decalf. Although its hand-painted silk is European in manufacture, the design elements and coloring technique reflect the influence of Chinese export silks. In a couture flourish, the painted wisteria—indebted to Japonisme—is hand embroidered with glass and metal beads that accent the flowers’ centers and define select areas of the leaves and branches, transforming the two-dimensional into the three-dimensional. This gallery features an animation of the robe à l’anglaise’s floral pattern being depicted using the hand-painting technique.

Blurred Blossoms

The muted pattern of blurred flowers on the 1750s–60s robe à la française achieves its subtle painterly effects through a labor-intensive technique known as chiné à la branche. Perfected in Lyon, France, during the first half of the eighteenth century, chiné silks were created by dyeing groups of warp threads known as “branches” before the fabric was woven. During the weaving process, the slight pulling of the threads created a soft, hazy appearance resembling a watercolor, an effect approximated by the lenticular wall, which features a detail of the “sleeping beauty.” Like other silks, when in motion chiné silks produced a rustling sound known as “scroop,” a combination of the words “scrape” and “whoop,” audible in this hallway.

The 1860s evening dress and the 1950s ball gown were produced by the easier and cheaper technique of warp printing, or chiné à la chaîne, which had all but replaced the more laborious chiné à la branche by the 1840s. In the dresses by Jonathan Anderson and Miuccia Prada and Raf Simons, the chiné-like patterns were created with digital printing, which emerged in the late 1980s. Anderson’s sheath is printed with a fuzzy image of an archival garment that follows the pattern of the dress, a trompe l’oeil effect that the designer dubbed a “ghost” of the house’s past. “The blurry aspect looks like a glitch,” Anderson explained, which he saw as a metaphor for fashion’s temporality.

Dior's Garden

Christian Dior’s fashions were greatly influenced by Impressionism. This inspiration is especially evident in his embrace of nature’s harmony and his advocacy for an idealized and ornamental femininity, both palpable in the “Miss Dior” dress. Bearing the same name as the designer’s first perfume, its millefleur embroidery—executed by Barbier—suggests the scent’s floral notes of iris, rose, jasmine, gardenia, narcissus, carnation, and lily of the valley (Dior’s favorite flower).

The House of Dior has repeatedly returned to “Miss Dior” as an emblem of its founder. The dress shown here is a miniature version of the original, inspired by the touring exhibition Le Théâtre de la Mode, organized to demonstrate the continued vitality of the haute couture following World War II. It was produced with the same virtuosic, artisanal exactitude as its full-scale sister, with silk flowers hand embroidered by Maison Lemarié. A 3D-printed plastic replica is displayed in the adjacent niche, allowing visitors to feel its form and the shapes of the flowers. Visitors are also encouraged to touch the surrounding urethane panels, which were cast from the flowers embroidered on Raf Simons’s interpretation of the “Miss Dior” dress and executed in black leather to allude to the eponymous perfume’s muskier base notes of leather, patchouli, and oakmoss.

Van Gogh’s Flowers

“Clothes that will stun the crowds in museum exhibitions in the future” was how New York Times fashion critic Bernadine Morris summarized Yves Saint Laurent’s spring/summer 1988 haute couture collection. A highlight was the “Irises” jacket shown here, a simulacrum of Vincent van Gogh’s 1889 painting. The jacket echoes the original’s cropped composition, zooming in even further on the curved and twisting lines of the irises. More remarkably, the embroidery amplifies the luminosity of Van Gogh’s colors and enhances the materiality of his thick, short, wavy brushstrokes, as the animation demonstrates.

According to Maison Lesage, who executed the embroidery, this artistic and technical tour de force involved 600 hours of handwork, 250 meters of ribbon, 200,000 beads, and 250,000 paillettes in 22 colors. Nine female artisans worked on it in sections, a technique emulated in the dress from Maison Margiela’s autumn/winter 2014–15 artisanal collection. Unlike Saint Laurent’s jacket, sewn seamlessly to create a unified “canvas,” Maison Margiela’s dress reflects its founder’s deconstructivism by appearing as a collage or patchwork of échantillons (samples)—an exquisite corpse formed from the detritus of the couture atelier.

Poppies

The poppy—like most flowers—has had dynamic and mutable meanings. Its association with mortality, however, has been a constant, as visualized in the animation. This symbolism was reinforced by John McCrae’s 1915 poem “In Flanders Fields” (read aloud in this gallery by Morgan Spector), which lauds the courage and laments the sacrifice of soldiers who died on the Western Front during World War I. Ana de Pombo’s dress evokes McCrae’s verses through its print: poppies in a field of wheat stain the dress like drops of blood that coagulate into appliqués over the chest and around the feet. Created just two years before the outbreak of World War II, the garment’s imagery is not only poignant but also prophetic.

Isaac Mizrahi’s dress makes explicit the poppy’s associations with blood and death. Sarah Burton achieves a similar effect in her dress, but she has replaced the poppy with its doppelganger, the anemone, another fragile and ephemeral blood-red flower. With its dreamlike sensibility, Viktor & Rolf’s ensemble references a different long-standing symbolic association of poppies—sleep—to which Ronald van der Kemp also alludes in his dress made from “dormant” vintage and leftover materials that he has reawakened.

Garthwaite's Garden

Anna Maria Garthwaite was an unlikely textile revolutionary. With no formal training, she arrived in the English silk-weaving capital of Spitalfields at age 40 in 1729 and quickly gained a reputation for her innovative approach to design. Until this point, the French were the acknowledged leaders of silk design, but Garthwaite helped usher in a recognizably English style by the 1740s. Airy, naturalistic, and realistically colored, this style was a far cry from the complex, overblown aesthetic that had predominated in the previous decade, represented by the “sleeping beauty” in this gallery.

Garthwaite was nearly sixty years old—but at the height of her pioneering powers—when she created the watercolor design incorporating sprigs of poppy, honeysuckle, and carnations that was then woven into the men’s waistcoat, a process detailed in the projection. Other designs shown here were inspired by her quintessentially English floral idiom, from Vivienne Westwood’s gender-swapping tribute to Felix Chabluk Smith’s deconstructivist reinterpretation of her idyllic florals, which have been invaded by weeds and spiders. Nicolas Ghesquière’s ensemble, inspired by eighteenth-century French menswear in The Costume Institute’s collection, exemplifies the type of Gallic gaudiness that Garthwaite opposed.

The Red Rose

“Rose is a rose is a rose is a rose.” In this tautological line from her 1913 poem “Sacred Emily,” Gertrude Stein materializes the red rose through repetition, giving it form, shape, and substance. There are few flowers that have been more lauded by poets and painters than the red rose, which has been invoked as a symbol of love, beauty, romance, passion, and sexuality. The rose has been equally embraced by designers, as represented here by garments that are sartorial sonnets and sculptures in and of themselves.

Philip Treacy’s startlingly lifelike headpiece evokes the flower’s fragility, as visualized in the animation and as also realized in the “sleeping beauty,” whose smell molecules, along with those of Yves Saint Laurent’s evening dress, emanate from the tubes on the wall. Saint Laurent’s lyrical confection as well as Pierpaolo Piccioli’s pay homage to their respective houses’ founders, who both shared a passion for roses and the color red.

For Domenico Dolce and Stefano Gabbana, roses hold personal memories. For Dolce, they remind him of the Palermo Botanical Garden, and for Gabbana, they recall his mother, who wore red lipstick infused with the flower’s smell.

The Specter of the Rose

The ghostly remains of perfumes past that remain embedded in the dresses on display have been translated into scented paint applied to the wall opposite. Paul Poiret’s “Rose d’Iribe” day dress—worn by his wife and muse, Denise—is emblazoned with a repeating pattern of calligraphic roses similar to the one by illustrator Paul Iribe that appears on Poiret’s label, which is dramatized evanescing into the ether in the animation. Scattered staining suggests a liberal application of scent to the dress, perhaps Poiret’s own “La Rose de Rosine” of 1912, among the first perfumes launched by a couturier.

The wearer of Marguerite de Wagner’s dress enhanced her toilette with a sachet shaped like a sealed envelope, which remains inside the front neckline. While the pouch is marked with the name of the D’Orsay perfume company and that of their scent, “Les Roses d’Orsay,” Christoph Drecoll’s dress has a more modest, possibly homemade sachet at the bust containing remnants of aromatic powder. Although the latter’s fragrance has all but vanished, vibrant roses of printed chiffon bloom through the black lace of the bodice, suggesting its elusive contents.

Scent of a Man

The ensembles displayed here were featured in Francesco Risso’s spring/summer 2024 collection for Marni, which centered on scent and its connections to memory. Each dress in the collection was sprayed with a scent by perfumer Daniela Andrier that was inspired by Risso’s memory of a chance encounter with a young man on a visit to Paris at the age of fourteen: “They rested their chin on my knee—for just a moment—then disappeared, leaving only their scent behind.”

The decoupage-like appearance of the ensembles references an elaborate nineteenth-century scrapbook found by the designer at a flea market in London. Both dresses are made of a cotton canvas base digitally printed with a floral pattern onto which hand-cut flowers from the same pattern have been glued to the surface, with some curled with a steam iron and others stitched with black thread. The ensemble opposite also features hand-painted aluminum flowers on wire stems that can only be fully appreciated in movement, when they resonate with fugitive vibrations that are difficult to pinpoint. Neither natural nor mechanical, the indeterminate noises (heard in this hallway) remind us that sound is no less pivotal in the recovery of memory than smell.

Smell of a Woman

The garments and accessories in this gallery were owned and worn by the singularly chic Millicent Rogers, granddaughter of Henry Huttleston Rogers—who cofounded Standard Oil with William and John D. Rockefeller—and an heiress to his fortune. In The Glass of Fashion (1954), Cecil Beaton describes Rogers as “extravagantly beautiful,” noting that “whatever the time or place, Millicent Rogers always left her imprint upon it” because her “originality was manifest even in the way she wore a bow or a scarf.”

Much has been written about Rogers’s inimitable sartorial aesthetic—how she would dress in styles that reflected her surroundings and how she would combine haute couture with regional dress. This gallery, however, focuses on a more elusive and intimate aspect of the socialite’s highly studied selfpresentation: her scent. Smell molecules taken from the objects on display have been replicated with the intention of discovering her individual olfactory imprint. These smells derive not only from Rogers’s choice of fragrance but also from her natural body odors and her singular habits and lifestyle, including what she ate, drank, and smoked. They also carry the aromas of her environments, which ranged from Austria and Jamaica to Virginia, New York, and New Mexico.

Reseda Luteola

Yellow is a notoriously divisive color in fashion. Located in the center of the visible spectrum, it may tend toward orange-red or green-brown, lending it a reputation for indeterminacy. For philosopher Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, who tackled the emotional implications of color in his 1810 Theory of Colours, yellow was “the colour nearest the light,” which, in its purest state, “has a serene, gay, softly exciting character,” but which is also “extremely liable to contamination, and produces a disagreeable effect if it is sullied.”

These fourteen garments testify to the enduring appeal of pure, unadulterated yellow over the past three centuries, suggesting a garden of sunny blooms. Indeed, the Latin word for yellow, flavus, likely derives from the root flos, meaning flower. This connection is reinforced in the sunlike disc featuring 41 the adjacent dress by Alber Elbaz that presides over the gallery.

The chemical structure of each dye determines the spectrum of visible light that it absorbs and reflects, as seen in the graphs paired with each object. Employing this analysis to identify the dyes used for each garment reveals the transition from natural to synthetic dyes. For thousands of years, the truest yellows were provided by the weld plant (Reseda luteola), sometimes in concert with spurge flax (Daphne gnidium). Synthetic dyes—invented in the mid-nineteenth century—took over from these natural sources, although recently, sustainability-minded designers such as Phoebe English have returned to weld as a source for vibrant, joyous yellows.

The Garden

“It is the hat that matters the most,” notes Rezia, the Italian milliner in Virginia Woolf’s novel Mrs. Dalloway (1925). Rezia’s observation was echoed by Christian Dior in his 1954 Little Dictionary of Fashion: “[A hat] is really the completion of your outfit and in another way, it is very often the best way to show your personality. It is easier to express yourself sometimes with your hat than it is with your clothes.”

If, as Dior believed, a hat “can make you gay, serious, dignified, happy,” then the wearers of the blossoms in this Edenic gallery would have felt not only lighthearted but also lightheaded, as many of the hats were designed to be worn to dinner and cocktails. They bloom with a wide variety of flowers, including lilacs, roses, violets, clovers, pansies, poppies, carnations, and geraniums, rendered with a verisimilitude as if freshly plucked from the garden. This surrealist interchange between nature and artifice, reality and illusion extends to the glass orbs containing granules that reproduce the smell molecules of several of the hats on display, challenging our olfactory expectations and, in the process, our powers of reception and perception.

Garments in this gallery have been reawakened by reproducing their smell molecules. The process involved extracting the molecules using a microfilter to trap air and moisture drawn through a glass barrel with a pump. The molecules were adsorbed and then analyzed using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry, allowing for their identification and replication. The peak molecules from the objects in this gallery listed below can be smelled in the corresponding numbered orb on this wall.

Garden Life

Gardening and embroidery were closely allied in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, with each discipline borrowing from the other to create intricate works of human artifice that both reflected and perfected nature’s untamed beauty. A style of gardening known as “embroidered” became popular throughout Europe, imitating the needlework seen on garments such as the women’s waistcoat—a type of informal jacket—from about 1615–20 displayed in this gallery. Its embroidery depicts an English garden seething with vitality: strawberries ripen, peapods burst open, and birds snatch at dragonflies and caterpillars, a dynamic arcadia brought to life by the animation on the domed ceiling. Some of the tactile experience of wearing such a densely embroidered garment—which combines braided gold threads, glass beads, silver wire, and metallic lace—is made available on the walls of the gallery.

Karl Lagerfeld’s evening gown is inspired by the embroidery style of the waistcoat and demonstrates his perpetual dialogue with the past. While appropriating the lavishness of the English Renaissance prototype, the designer also cleverly references one of the House of Chanel’s most recognizable icons: the coiling embroidery of sequins, faux pearls, and crystals forms the interlocking C’s of the house’s logo.

Insects

Compelled by the spirit of the Enlightenment, illustrated natural history publications in the eighteenth century sparked an increase not only in scientific knowledge but also in the aesthetic appreciation of animal species, including insects. Bees, flies, mosquitoes, and beetles crowd the surface of the men’s waistcoat displayed here, creating a glossy carapace—itself made from the spoils of another “lowly” insect, the silkworm—that announced the wearer’s entomophilia as well as his allegiance to fashion, which had begun to embrace all manner of faunal subjects.

Waistcoats and buttons were the components of male attire most adaptable to momentary fads in the late eighteenth century, allowing stylish men to display their taste as well as their knowledge of current events and recent discoveries. At the center of the gallery, three sets of buttons offer an anthology of techniques used to represent insect forms, from painting on glass to using actual “specimens” collected from nature, such as feathers (substituting for moth wings) and seaweed, shells, and dried insect bodies to suggest tidal ecosystems. Magnifying the buttons on the domed ceiling—as if through a microscope—allows for a greater appreciation of the materiality and workmanship of these miniature, wearable cabinets of curiosity.

Beetle Wings

When asked if his study of nature had yielded any insights about the character of the divine, British Indian evolutionary biologist J. B. S. Haldane is famously said to have answered that God, if he exists, displayed “an inordinate fondness for beetles.” Indeed, beetles account for roughly one quarter—four hundred thousand—of all described animal species on earth. Charmed by their kaleidoscopic coloring and iridescence, humans have displayed a similar fondness for these insects, particularly as a form of ornament. Indigenous cultures throughout the world—from Southeast Asia and India to the Americas—have for centuries made use of the outer wing casings, or elytra, of so-called jewel beetles as a form of bodily and sartorial embellishment. In the nineteenth century, as colonial empires expanded intercontinental trade links, these curiosities entered the Western fashion system as markers of novelty and dominance.

The garments displayed here engage with this legacy of adornment in a variety of ways, ranging from the hyperreal, as with Olivia Cheng’s organza dress covered with sustainably harvested jewel beetles, to the abstract, as in Dries Van Noten’s ensemble decorated with artificial beetle-wing sequins. The latter was inspired by a 2002 installation in the Palais Royal in Brussels, in which the artist Jan Fabre covered the ceiling of one room with over 1.5 million actual elytra (an effect simulated in the animation), offering a synthetic vision of the dazzling play of light on the real thing.

Butterflies

“Literature and butterflies are the two sweetest passions known to man,” novelist Vladimir Nabokov once professed. Butterflies have fluttered onto the pages of poets through countless metaphors, but perhaps the most enduring and universal is transformation, stemming from their unique life cycle— from caterpillar to chrysalis to butterfly—which figuratively embodies life, death, and rebirth. Charles James reflected and realized the insect’s ephemeral beauty in his “Butterfly” ball gown, comprising a narrow, body-hugging “chrysalis” sheath of pleated brown silk chiffon over a cream silk satin ground, and an exuberant “winged” bustle skirt of nylon tulle in layers of brown, rust, and lavender that effect a butterfly’s multilayered coloration. As its “sleeping beauty” doppelganger reveals, however, the fragility of the dress’s materials combined with the volatility of its construction makes its destruction inevitable.

Sarah Burton’s dress was featured in her debut collection for Alexander McQueen, after its eponymous founder—and Burton’s mentor—took his own life eight months earlier. The dress is veneered with turkey feathers cut, dyed, and painted to emulate the iconic pattern of the monarch butterfly, which symbolizes hope, resilience, and endurance. These qualities are encapsulated in the butterfly’s annual three-thousand-mile migration across North America, a journey evoked in the animation filling the gallery.

The Birds

Alexander McQueen once declared, “Birds in flight fascinate me.” One of his favorite films was Alfred Hitchcock’s 1963 thriller The Birds, which inspired his spring/summer 1995 collection, including the jacket displayed at the center of this gallery. Made from orange wool twill, it features a swarm of swallows screen printed by Simon Ungless and Andrew Groves and brought to life in the animation. Individual birds gradually materialize from the ominous black cloud of swallows at the exaggerated shoulders, swooping around the body of the jacket and increasing in size but decreasing in number toward the hem.

Despite their delicacy, the swallows depicted on the evening dress by Madeleine Vionnet are no less menacing. Hand embroidered with both matte and shiny sequins on a black silk tulle overdress, the raptors ominously encircle the body of the wearer. The dress formed part of Vionnet’s autumn/winter 1938–39 collection, launched just one year before the outbreak of World War II. Against this backdrop, the menacing sensibility of the swallows is supplanted by an intense melancholia and sense of deathliness.

The Nightingale and the Rose

While birds have served as fashion’s muse, they have also been its victims. Never was this truer than in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, when millinery ornamented with the bodies of taxidermy birds enjoyed a cruel vogue, resulting in hundreds of thousands of birds being killed annually. Sacrificed for the love of fashion, these avian casualties find a melancholy correlative in the nightingale at the center of Oscar Wilde’s fairytale “The Nightingale and the Rose” (1888), an excerpt from which is read aloud in the gallery by Elizabeth Debicki. In Wilde’s story, the titular bird pours out its lifeblood by piercing its breast on the thorn of a rosebush in order to produce a perfect red rose for a lovesick boy, a tragedy brought to life (and death) by Simon Costin’s necklace.

Encircling the gallery is an amphitheater of taxidermy millinery spanning the time of Wilde’s tale through the early twentieth century, when the activism of conservationists began to curtail the trend. Ryunosuke Okazaki’s avian ensemble stands sentinel amid this macabre index of both brutality and creativity. X-rays reveal the bones, wires, glass beads, and stuffing used by taxidermists to stop time and make these ornithological specimens—typically comprised of parts from different birds—appear ready to take flight.

Marine Life

“Everyone knows meditation and water are wedded forever,” Herman Melville exclaimed in Moby-Dick; or, The Whale (1851), a sentiment echoed in the garments in this gallery—sartorial seascapes connected by the poetics of science. Iris van Herpen’s vaporous creations were inspired by Santiago Ramón y Cajal’s intricate drawings of the central nervous system, which she relates to Hydrozoa, a class of small, delicately branched marine organisms that “embroider the oceans like aqueous fabrics, forming layers of living lace.” Alexander McQueen’s dresses express his concerns over global warming, which he merged with Charles Darwin’s theories of evolution.

Environmentalism also underlies the dresses by Richard Malone and Rushemy Botter and Lisi Herrebrugh. The former is made from ECONYL—a yarn regenerated from nylon waste, including industrial ocean plastic and fishing nets—and the latter from a fabric comprising 70 percent biodegradable polyamide and 30 percent SeaCell, a mix of cellulose and seaweed. Botter and Herrebrugh describe their fashions as “aquatic wear,” a term equally applicable to the Olivier Theyskens evening ensemble. Like the “sleeping beauty” from the 1860s, whose silhouette it emulates, Theyskens’s ensemble is made from moiré silk taffeta, its distinctive rippled appearance suggesting sunlight reflecting on water, an effect captured in the animation.

Venus

“New spangles, luminous, iridescent, like jewels drowned in the sea.” This is how Harper’s Bazaar editor-in-chief Carmel Snow described the two ball gowns by Christian Dior displayed here when they made their debut as part of his autumn/winter 1949–50 collection. Their mythological nomenclature— referencing the Roman deities Venus, goddess of love, beauty, and passion, and Juno, goddess of marriage—is mere pretext for an exuberant demonstration of material abundance, in the form of glistening aquatic embroidery from the firm of Rébé.

Dior’s iteration of Venus evokes the froth of her legendary birth from the sea with a cascading trained peplum of soft gray tulle, each undulation embroidered by hand with crystals and iridescent paillettes (given life in the animation). With “Junon,” the blue-green sequins that edge the individual sections of the scalloped skirt also impart an undeniably aqueous effect, despite nominally referencing the feathers of Juno’s traditional animal attendant, the peacock. Maria Grazia Chiuri’s 2017 reinterpretation retains the scalloped skirt construction but eliminates the embroidery, opting instead for soft, fan-pleated mother-of-pearl shades to enhance the allusion to shells. Meanwhile, H&M’s pink goddess dress was quite literally born from the waves—it is made from shell-pink BIONIC, a woven polyester produced from recycled ocean waste.

Seashells

The enduring appeal of seashells stems in part from their ability to amplify ambient noise. Alexander McQueen exploited this inherent resonance in his “razor clamshell” dress, which can be heard in this hallway. The dress was featured in his “Voss” collection, which related Victorian depictions of insanity to the sublime beauty of nature. On the runway, it was modeled by Erin O’Connor, who simulated a nervous breakdown, clutching fistfuls of shells and violently shattering them on the floor.

Fossiliferous limestone is evoked in Iris van Herpen’s 3D-printed top, with its strata of fine lines mirroring bands of calcified shell deposits at the bottom of the ocean. Ammonites—ocean-dwelling mollusks that died out about 66 million years ago—are re-created in Bea Szenfeld’s tunic. Individual paper discs in graduating sizes have been threaded onto nylon filaments, with each layer separated by small beads, emulating the tightly wound shells of the cephalopods.

Functional as an encasement, the seashell has often been incorporated into handbag designs. Judith Leiber’s twentieth-century versions recall a tradition of shell purses that surged in popularity during the previous century. The mother-of-pearl coin purse from the earlier period is hand painted with pink and yellow roses, drawing on the splendor of the seashell while alluding to its symbiotic relationship with nature’s earthly wonders.

The Siren

In her original incarnation, the mythological siren was portrayed as a bird-woman. By the seventh century she was depicted with a fish tail, and by the Middle Ages her reputation as a deadly seadwelling seductress was firmly established. In much of Africa and the African diaspora, the archetype of the siren finds a correlation in Mami Wata (Mother Water). Her regional analog, Mongwa Wa Letsa (Someone of the Lake) inspired Thebe Magugu’s “Shipwreck” ensemble. Its print derives from a French engraving depicting the Great Hurricane of 1780, a scene evoked in the film projected in this gallery, which is accompanied by N’gadie Roberts’s 2022 poem “Mami Wata,” read by Cynthia Erivo. Mami Wata’s incorporeal form is realized in Torishéju Dumi’s ensembles made from deadstock offcuts pieced together on the bias and finished with overlock stitchwork, creating a rippling effect that manifests a human-teleost (bony fish) hybrid.

The archetype of the siren is embodied in sensual form in Charles James’s and Daniel Roseberry’s evening dresses, which emphasize the wearer’s waist and hips while obscuring her legs in a graceful fish tail. Roseberry enhances this surrealistic transmogrification through an outsize fish-skeleton necklace of lacquered wood—a playful reference to Elsa Schiaparelli’s iconic and iconoclastic “Lobster” dress, which she created with Salvador Dalí in 1937.

Snakes

While Mami Wata is usually depicted with a woman’s upper body and a fish’s or serpent’s lower body, she sometimes also sports a snake around her neck, an effect replicated in the evening dress from about 1905. Possibly worn for fancy dress, the serpent is partially camouflaged against the secondskin-like sequined sheath, a prototype of Norman Norell’s “mermaid” dress on display in the following gallery. In contrast, Iris van Herpen’s writhing mass of multiple serpentine bodies capitalizes on the uncanny appeal of the swarm to conjure a state of psychological ambiguity. The designer described the dress as an expression of her thoughts before a skydiving jump, when “all my energy is in my mind and I feel as though my head is snaking through thousands of bends.”

While the garments employ vastly different materials—gelatin sequins on the Edwardian gown and molded thermoplastic sheets on Van Herpen’s dress—both evoke the reptile’s contorted locomotion and glossy, scaled body, as a cipher for seductive femininity and for psychological slipperiness, respectively. Each also offers the elongated frame and writhing motion of the snake as an alternative to our own mammalian physique, an idea captured directly in the animation below Van Herpen’s dress.

The Mermaid

The mermaid was a subject of fascination for Romantic artists, who often portrayed her as an enchantress whose beguiling powers and emotional depth saw her straddling fantasy and reality. This dualism is expressed sartorially in Norman Norell’s sequined “mermaid” dress, which epitomizes the designer’s concept of streamlined glamour. Individual sequins were attached by hand with two stitches to ensure they lay flat, maximizing light reflection. The dress’s simple silhouette and the intricacy of its surface decoration marry American practicality and French haute-couture finesse. Marc Jacobs and Michael Kors both reprised Norell’s mermaid design, extending his lineage of relaxed opulence. The shimmering surfaces of all three dresses are reflected in the film shown here, which depicts sequins—the same type used by Norell—suspended in water. Joseph Altuzarra explored the mermaid’s sonic allure in a dress embroidered with metal paillettes, which in movement resound like gentle waves, the sound of which fills this gallery. An even softer sound emanates from Thom Browne’s evening ensemble. Though not directly inspired by Norell’s dress, Browne’s design expands its predecessor’s demi-couture sensibility through its complexity and refinement of technique.

The Mermaid Bride

The bridal ensemble in this gallery was worn by New York socialite Natalie Potter for her wedding to financier William Conkling Ladd on December 4, 1930. Its dramatic, cathedral-length train features interlocking scallops that recall undulating ocean waves and the concentric circles of seashells. Designed by Callot Soeurs at the dawn of the Great Depression, it is devoid of lavish surface embellishment and is made of a blend of silk and cellulose acetate, an emerging synthetic fiber that provided an inexpensive alternative to silk. While the basque-style overblouse recalls the waistless, androgynous silhouette of the youthful 1920s garçonne, the sleek skirt with its elongated hemline anticipates the more mature, disciplined, and feminine aesthetic of the 1930s.

Potter posed in her wedding ensemble for a portrait by legendary photographer Adolf de Meyer, published in Harper’s Bazaar in January 1931 and displayed on the adjacent screen. Although the ensemble’s sweeping train is out of the frame, the photograph reveals a detail that is now missing from the overblouse: a cascading cluster of white artificial carnations falling over the left hip. For more information about Potter, her wedding, and her ensemble, scan the QR code on the screen to converse with her using artificial intelligence (AI).