Conservator Jean-François de Lapérouse and Nahla Nassar, courier from The Khalili Collection, examine loan objects received for the exhibition Court and Cosmos: The Great Age of the Seljuqs. Photo by David Sastre

«When I started having dreams about placing one small thing just two millimeters closer to another small thing, I knew that I had succumbed to installationitis. This is a rare disease outside of the museum world, perhaps also experienced by people who design the windows of fancy jewelry stores, but one that is familiar to the range of people involved with installing art exhibitions. Within the space of two weeks in April, a large team at The Met positioned 270 objects—ranging from coins to large stone sculptures—in cases and on walls to prepare for the opening of Court and Cosmos: The Great Age of the Seljuqs, on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through July 24, 2016.»

About one third of the objects on display belong to The Met, but the rest came from 52 different private and public collections across North America, Europe, and the Middle East. The exhibition's curators—Deniz Beyazit, Martina Rugiadi, and I—had spent several years visiting museums and collectors seeking the best Seljuq objects we could find. Thanks to the remarkable generosity of the lenders, we are able to present the story of all the Seljuqs, from their origins in 10th-century Turkmenistan to their ultimate territories in Iran, Anatolia, Northern Syria, and Iraq.

The other story, however, of how the Museum's staff comes together to ensure that objects are shown in a meaningful and visually appealing way, is hidden from the public's view, much as a play or concert is what performers, conductors, playwrights, or composers want the audience to see, and not the hours of rehearsal or the tinkering with stage lights.

Just arranging the schedule of which objects will arrive on what day is like a military operation. Registrar Aileen Chuk and her staff worked with Department of Islamic Art Research Assistant Michael Falcetano to review the agreements with lenders in order to determine or dictate what day the couriers would arrive. For Turkmenistan, where museums are making an extended loan of antiquities to the United States for the first time, two couriers accompanied their objects. Fortunately, Maks and Ynanch were happy to observe their objects being condition-checked and then installed, so despite the novelty of the situation, everything went smoothly.

Conservation Preparator Matthew Cumbie and Assistant Curator Deniz Beyazit install a mina'i bowl. Photo by David Sastre

Once the objects conservators gave the okay, the installers (also called preparators) who make the mounts arrived and began to produce metal holders for the ceramics and other small objects needing support. Where the conservators train an eagle eye on every tiny crack or discoloration, the installers have to bend the metal mounts at just the right angle to follow the designer's plan, catch the light correctly, and satisfy the curator's vision. In addition they paint the visible part of the mount so it is not only unobtrusive but in the same color or even pattern as the object it holds. Heaven forbid that a shiny, metal L-hook should divert the viewer's attention from a work of art! For installers, installationitis is probably a chronic condition and actually a job requirement; for curators, it can spill over to one's house or office—not necessarily the usual place for obsessive-compulsive straightening of paintings or arranging one's possessions in tidy, symmetrical rows.

Where large, heavy items are concerned, the skills of engineers, machinists, and riggers are de rigueur. In Court and Cosmos, for example, we were under the initial impression that a large tombstone borrowed from the Benaki Museum in Athens was going to weigh 1,000 pounds. However, once it arrived, it became clear that it actually weighed 1,000 kilograms, or 2,200 pounds. This could have caused a problem if the pedestal and the floor beneath it could not carry the load. Fortunately the highly knowledgeable and experienced Taylor Miller, senior associate buildings manager, came to the rescue and we were able to safely install the piece.

Riggers position a large stucco panel on the gallery wall. Photo by David Sastre

While lifting the tombstone into place required a fork-lift truck, straps, and men to hold the piece upright, its placement on the pedestal was straightforward. Another stone grave marker from Turkmenistan, however, posed different challenges. The sculpture of a bearded figure called a "baba," which exemplifies pre-Islamic burial practices in Central Asia and elsewhere, consists of two pieces: a head and a body. Our job was to mount it upright and position the head accurately on its shoulders. While once again the riggers with the fork-lift truck were front and center, this job required two of them to hold the body of the sculpture in the air while the truck moved into position.

The aptly named Derrick Williams, notable for his great height and strength, and a colleague of his held the stone weighing hundreds of pounds for what seemed like an interminable amount of time. They didn't even break a sweat, maintaining the calm and purposeful demeanor that characterizes all of the teams who install exhibitions and galleries.

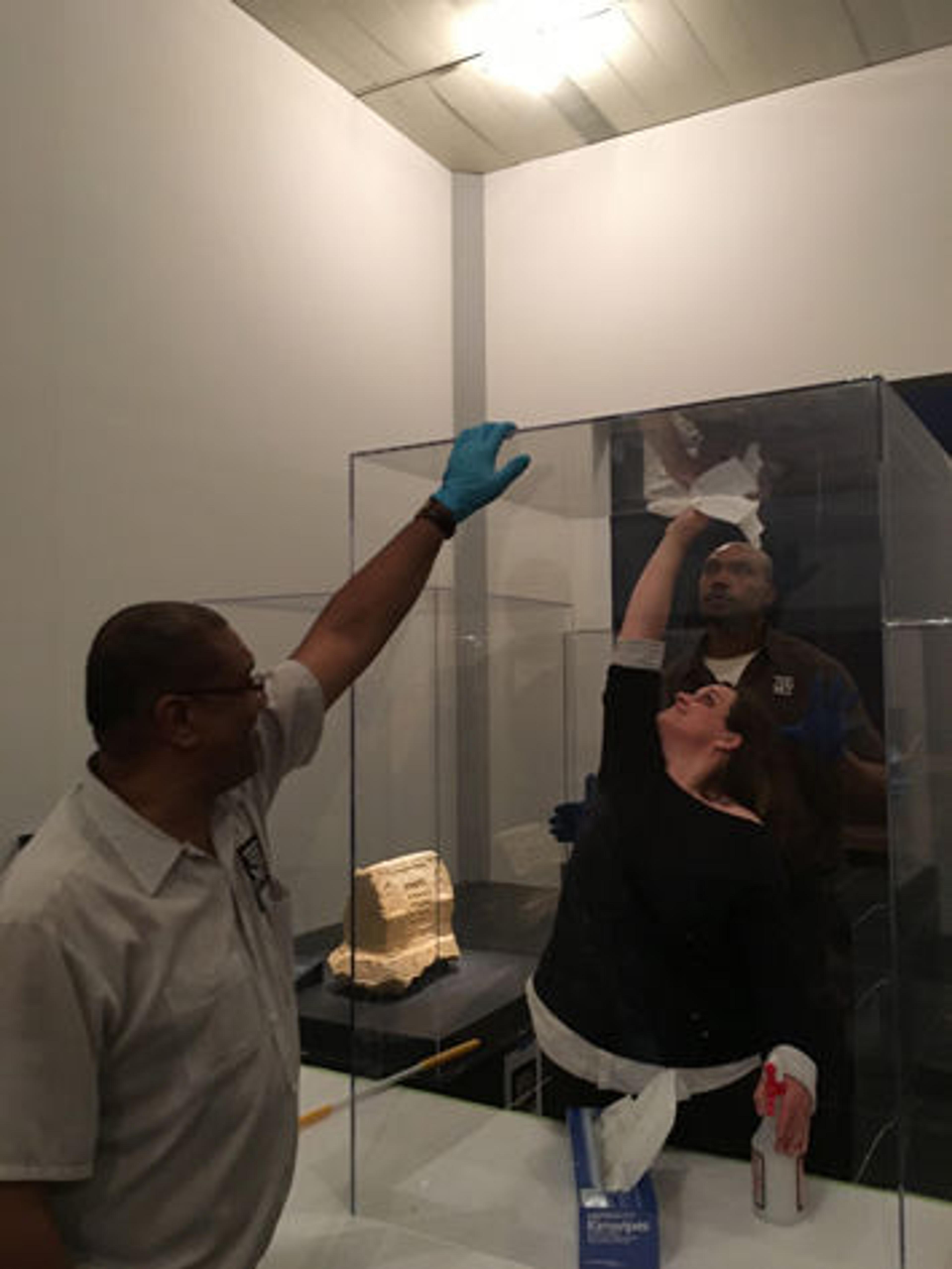

Left: Annick Des Roches, collections manager in the Department of Islamic Art, and riggers Ray Abensetts and Derrick Williams clean the interior of a vitrine. Photo by Michael Falcetano

Once all the pieces have been placed according to plan and all the huge Plexiglas vitrines lifted over them by the Plexiglas team and technicians are secured, lighting the exhibition begins in earnest. Now a team of three—Rich Lichte, Clint Coller, and Amy Nelson—rule the skies (or at least the upper reaches of the exhibition galleries) from their rigs. In Court and Cosmos, the large number of brass objects inlaid with copper and silver required the greatest skill to highlight the fascinating details while avoiding glare or excessive shadows. Sometimes a spotlight would be aimed at an object from across the room. Yet somehow the color and nuance of the light would bring out the best qualities of the work of art.

After all the teams finished their duties, the curators and designers reviewed the exhibition, marking every spot where the paint was scratched or something needed cleaning. As if by magic, by the morning of the exhibition's opening day the painters had painted out the scuffs and the cleaners had mopped the floors. Now one more exhibition was ready for the public, who might never suspect that such a large and specialized team of people, all afflicted to a greater or lesser degree with installationitis, would have converged in such a short space of time to produce such a large exhibition so seamlessly.

Related Link

Court and Cosmos: The Great Age of the Seljuqs, on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through July 24, 2016