Petrit Halilaj’s rooftop commission, ABETARE (2024), consists of sculptures based on student graffiti—a constellation of words, images, and symbols from scribbles found on the desks of his former elementary school in the village of Runik, in the artist’s native Kosovo. He attended the school between 1992 and 1997, just before the brutal war in Kosovo of 1998 and ’99, during which ethnic Albanians like Halilaj and his family were subjected to an inhumane campaign of repression and dispersion by Yugoslav (Serbian) forces. Halilaj visited Runik in 2010 to find that the building was slated for demolition so that a new school could be built. During the artist’s 2010 visit, on the day before the school was to be destroyed, Halilaj filmed and photographed the building, the desk graffiti, and the students as they roamed the building one last time and ransacked its inventory. This archive of photographs and notes served as a model for the metal sculptures that eventually became the installation.

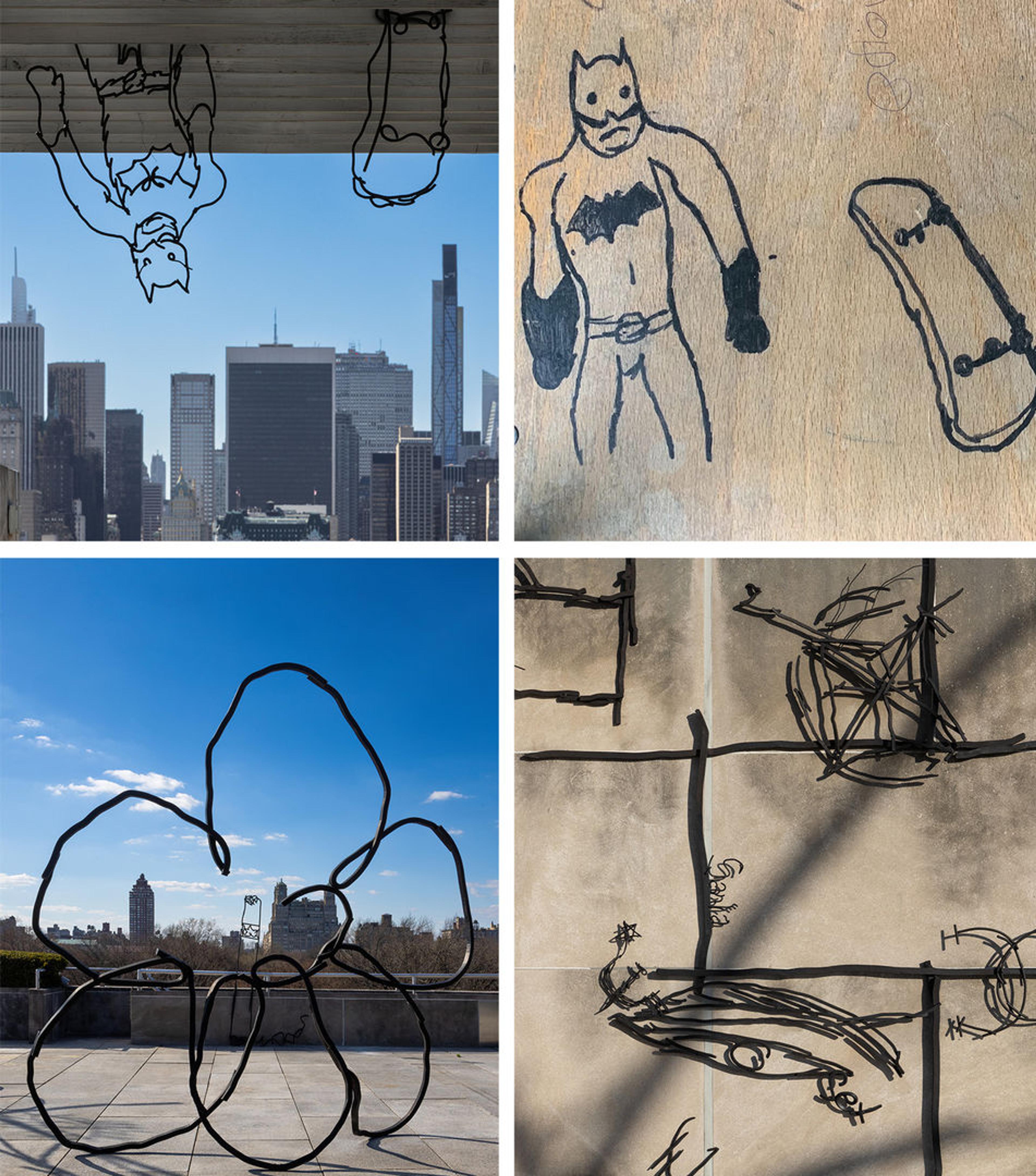

Left: Installation view of ABETARE (2024). Right: Close-up of desk graffiti

ABETARE cannot be separated from the artist’s experiences during the Kosovan War. Strikingly, the location for ABETARE’s first presentation in 2015 was Cologne, one of the most heavily damaged cities in all of Germany during WWII, much as Runik was bombed and decimated during the war in Kosovo. And yet, the fact that the village school was lost not during the war in Kosovo, but over a decade later in an independent, postwar Kosovo for reasons that had nothing to do with the war, is symptomatic of the way Halilaj deals with trauma in his work. While the element of destruction—also present in the children’s playful vandalism—associates the artist’s 2010 visit to Runik with the war in Kosovo and his own experience of these events, the connection is neither direct nor unequivocal. Much like the anticipated destruction of the school on the day after Halilaj’s visit, ABETARE recalls the village’s ruin twenty years earlier but cannot simply be conflated with it.

View of desks in Skopje

Halilaj’s sculptures on The Met’s rooftop point toward his childhood experiences but they do not express them directly. Instead, they act as what psychoanalysts call “screen memories” (Deckerinnerungen), that is, memories of events or experiences that effectively obscure other, more traumatic recollections. Like all screen memories, the sculptures are, in this sense, not monuments of memory but rather monuments of forgetfulness: memory without recall. In the project’s original iteration in Cologne, the sculptures are suspended from the ceiling or are pinned on the walls in such a way that the viewer experiences them as if they are stacked on top of or behind each other; the artist deliberately staged instances of steganographia, the art of hiding or covering (in Greek “steganos” meaning covered) textual information in another medium or object. While Halilaj’s text-based sculptures contain potentially intelligible words and messages, the way in which these words are deployed in space—behind and on top of each other, extended into space—makes their deciphering difficult, screening the installation’s text from becoming fully transparent to the viewer.

Three views of the installation and one detail of a desk Halilaj photographed

Halilaj added drawings from the desks of other schools in the former Yugoslavia as the basis for his sculptures (including Serbian ones) specifically for The Met commission of ABETARE. Yet here again, it’s important to recognize the element of resistance, for ABETARE challenges the worship of children and their supposed access to a pristine world of exquisite purity referenced by the nineteenth-century French poet Charles Baudelaire, among many others. For Baudelaire, children see everything in a state of newness and are “always drunk.” While the creativity of the desktop graffiti and the sculptures it inspired may partially point in that direction, with Halilaj, the case is more complicated. Not only do the photos the artist took inside his former school show graffiti of automatic weapons and other symbols of violence and aggression among names of pop stars and cute drawings of flowers, but the film he made during his visit further demonstrates how the students brutally destroy their school’s inventory on the eve of its demolition, suggesting that the image of the child implicit in ABETARE is, again, full of ambivalence and contradictory impulses.

Installation view of ABETARE (2024)

The same is true for the sculptures. Throughout ABETARE, the uncanny transposition of the small drawings and scribbles from the students’ desks into the now-monumental medium of sculpture is only partially neutralized by the elegance and aesthetic allure of these art objects. Nowhere is this felt as intensely as in the case of the large spider that stands on the Museum’s roof. Spiders are symbols of patience and persistence, yet as arachnids, they also belong to a species whose look and behavior we have trouble assimilating or describing in anthropomorphic terms. In this sense, Halilaj’s spider embodies in a very precise manner the enduring element of alienation, the lack of understanding, and the pervasive sense of resistance and “otherness” that is a key characteristic of the ABETARE sculptures and the traumatic memories they (fail to) channel. Even though these monuments are based on an archive of potentially recognizable forms, we don’t actually see this welded graffiti in bronze and stainless steel for what it originally was, just as most of us do not understand the Albanian words that some of the sculptures spell out. As we visit ABETARE, we move around its space as if we are in a kind of mnemonic exile, a place full of cryptic scribbles welded in bronze and steel whose meaning we cannot grasp, no matter how hard we try. The artist places us, the visitors, almost as he was when he visited his former school in 2010.

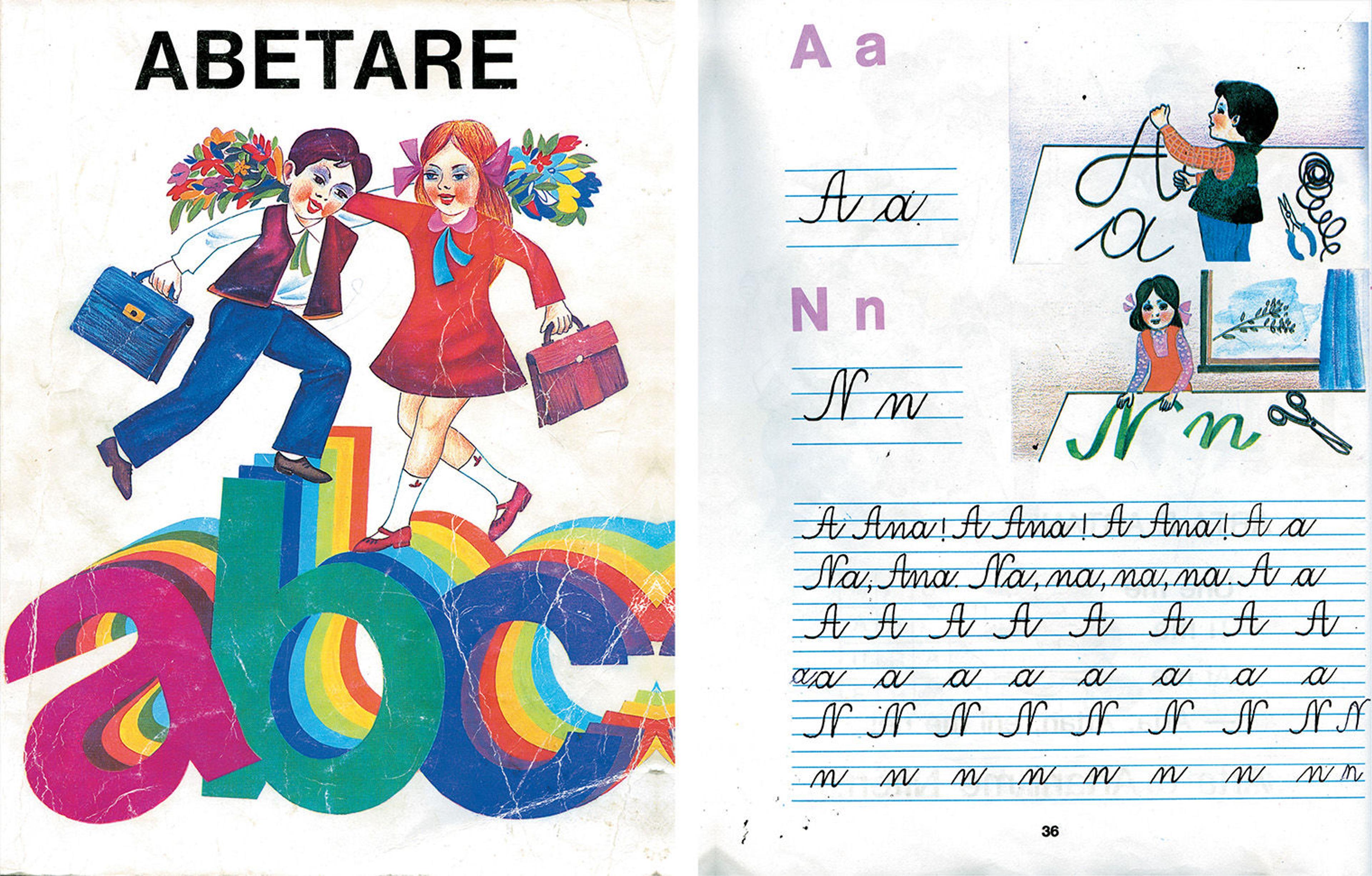

The front cover of an abecedarium and one of its pages

It is perhaps ironic, in this context, that the word ABETARE, which in Albanian refers to an abecedarium, a manual for learning how to write, is reminiscent of the Italian verb abitare, which means “to dwell.” If writing, or language by extension, is supposed to give us access to the world so we can inhabit it (the English word inhabit is related to abitare by way of Latin habitus), then Halilaj’s transposition of his own experience of forced uprooting into an installation entitled ABETARE teaches us that inhabiting (abitare), in language and otherwise, is not always the same as being “at home.” In what sense, exactly? Being at home, I want to suggest, refers to a type of dwelling that does not require learning and decipherment, like an ABETARE, because everything around us already makes sense without effort. Yet the certainty of home has very little in common with Halilaj's work. Different scales and times, distance and proximity, legibility and obscurity, freely mingle and interact with each other in the sculpture so that past, present, and future memories—or the lack thereof—can never be separated from each other.

Two details of ABETARE (2024)

Halilaj’s transpositions of two-dimensional drawings into three-dimensional space not only presuppose translation and transfer but they also contribute to, and even produce, the effect of radical, programmatic unreadability. Once-tiny words and symbols now appear abnormally oversized, while the obscene palimpsest from one of the school desks is now spaced out in such a way that its constituent elements, while still individually recognizable, now function in ways that are completely incompatible with their original. As scale and position shift, the sculptures, their beauty and affect, take the place of memories: the archive of graffiti Halilaj took with him after his visit to Runik; the school’s anticipated destruction; and the way it connected with the events twenty years prior—that had themselves shielded a trauma whose original spelling they could hint at, but not retrieve.

Two details of ABETARE (2024)

Understood as a set of sculptural drawings that translate into three dimensions—a series of two-dimensional symbols and letters connected to the artist’s biography—the objects installed on the rooftop of The Met may additionally be interpreted as the artist’s self-portrait. As the philosopher Jacques Derrida reminds us, when we try to draw our own self-portrait, we cannot see what we draw as our hand outlines a face, our own, that remains invisible to us: blind drawing. And so it goes with ABETARE, which swaps the space of the desk for the “negative” space of the sculpture’s surroundings: New York’s skyscrapers, Central Park, and, eventually, the sky. By transposing his self-portrait into space, Halilaj fundamentally alters the coordinates that determine his and our interaction with the students’ drawings. As every visitor quickly discovers, seeing or reading these sculptures inscribed into the sky is very different from seeing images or scribbles on a solid surface, such as a desk. For there is now no ground to our effort to read and to understand; or rather, space itself is the ground, leading to a kind of hermeneutic vertigo that seems to hurl us into the void.