Assistant Curator Stephanie Herdrich in the American Painters in Italy: From Copley to Sargent exhibition gallery

The great pleasure of American Painters in Italy: From Copley to Sargent is that it reveals history to be both transferable and transmutable. On view in gallery 773 through June 17, the American Wing's exhibition of paintings and works on paper takes as its subject the landscape, culture, and history of an old European country, as seen through the eyes of foreigners who sought to imbue the art of their own young and idealistic nation with culture and legacy.

When I met Stephanie Herdrich, the exhibition's curator, I wanted to know what drew American painters to Italy more so than to anywhere else. The answer, it turned out, was both familiar—Italy was attractive then for the same reasons it is today—and strangely unknowable—its art is filled with wonders and expectations, elucidations and traditions, truths to withhold and to reveal.

Will Fenstermaker: What was it about Italy that so captured the American imagination?

Stephanie Herdrich: So many things! American painters, from the very beginning, had great interest in Italy's art—the antiquities and ruins, the monuments of the Renaissance—and the sense of history. Coming from a young nation, they were particularly captivated by the rise and fall of the Roman Empire.

Will Fenstermaker: Their interest was a way of siphoning some of that.

William Stanley Haseltine (American, 1835–1900). Baths of Trajan (Sette Sale, Villa Brancaccio, Rome), ca. 1882. Watercolor, gouache, and charcoal on blue wove paper, 15 3/16 x 22 1/16 in. (38.6 x 56 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Roger Plowden, 1967 (67.173.1)

Stephanie Herdrich: Italy was picturesque and had great art, but it also provoked greater intellectual questions about nations and government and history. Aspiring American artists started going to Italy from the earliest days of the colonies. For painters like John Singleton Copley and Benjamin West, there was not much art to look at in this country, and they felt compelled to see and study great works in order to improve their own art.

This sense of acquiring culture also overlaps with a tourist agenda. The Grand Tour, which was solidified at this point in Britain and Europe, made Italy an essential destination and cast Rome as one of the great capitals of Europe.

Will Fenstermaker: Were artists who traveled to Italy looking at other artists who traveled there before them?

Stephanie Herdrich: American painters were certainly looking at places that other artists painted and following in their footsteps. William Trost Richards's watercolor Lago Avernus was inspired by J. M. W. Turner, who had painted at the same lake. Whistler, Sargent, and Prendergast were aware of the iconic views of Venice painted by Old Masters such as Canaletto and Guardi.

Of course, there's also an important literary tradition surrounding Italy. For example, when Sargent was drawing and painting images of Rome as a child, he was using Nathaniel Hawthorne's The Marble Faun as a guidebook and visiting the sites and artistic monuments that Hawthorne had described.

William Trost Richard (American, 1833–1905). Lago Avernus, ca. 1867–70. Watercolor, gouache, and graphite on blue wove paper, 4 1/2 x 9 1/2 in. (11.4 x 24.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Morris K. Jesup Fund, 2001 (2001.39)

Will Fenstermaker: What were the highlights of the Grand Tour?

Stephanie Herdrich: For Americans, it would usually be London, Paris, Rome, the Campagna around Rome, and Venice.

Will Fenstermaker: Which brings us, of course, to the organization of this exhibition, which is roughly divided into copies of Italian art, Rome and the Campagna, and Venice.

Stephanie Herdrich: Exactly! American artists visited and painted at these iconic locations in Italy, and our collection reflects that. I want to highlight that all of the paintings and drawings in this show are from The Met collection. The oil paintings are taken from our open storage and the works on paper are rarely on view. We are able to show them only for limited periods because of their sensitivity to light. We hope that visitors will become accustomed to visiting this gallery in the Luce Center for exhibitions that highlight the breadth and depth of the American Wing's collection. I hope we'll be able to do more installations of works on paper here—it's a great space for works on paper because there's no natural light and the scale is good.

Will Fenstermaker: It is a very intimate gallery. It lends a sense of discovery when you come across it, after traversing through the open storage. You've come upon this hidden gem.

Stephanie Herdrich: Right. The Luce gallery is a bit off the beaten path. So I do hope visitors will have that sense of discovery when they arrive. . . . We can use that metaphor. That's a theme that runs through the show: Why travel? You get that sense of discovery when you travel and see things differently. For example, the Italian light is different.

Will Fenstermaker: Yes! That's something that I love about this exhibition. The three sections aren't labelled, but you can almost pick out which paintings go where just by the quality of the light. Tuscany has that warmth; the Campagna is cool and crisp. You can see it in the paint.

Stephanie Herdrich: And Venice is something entirely different. The collection really dictated the sections, but then there are all of these overlaps.

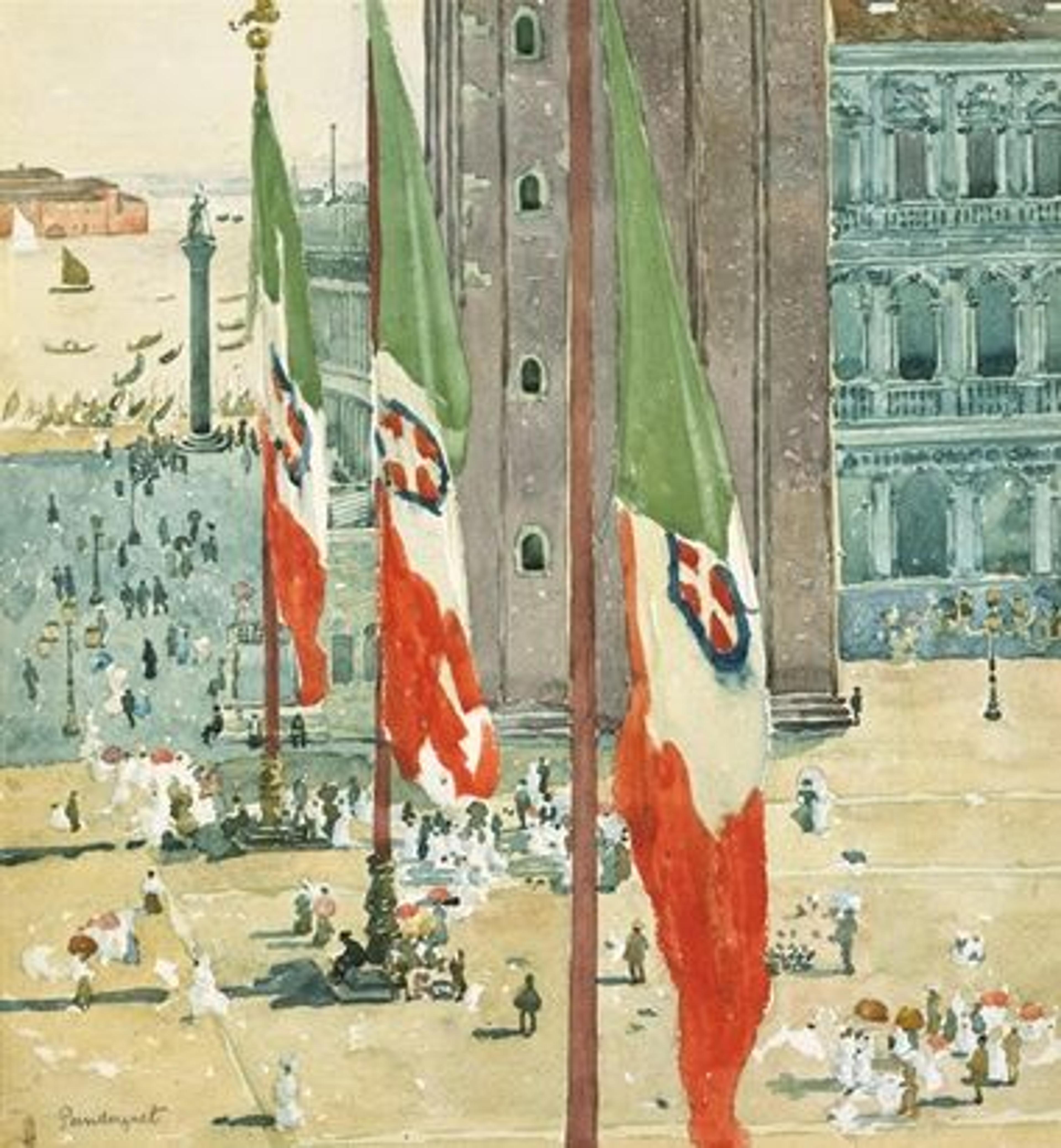

Right: Maurice Brazil Prendergast (American, 1858–1924). Piazza di San Marco, ca. 1898–99. Watercolor and graphite on off-white wove paper, 16 11/16 x 15 3/8 in. (42.4 x 39.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Estate of Mrs. Edward Robinson, 1952 (52.126.6)

Will Fenstermaker: Sure, like a copy that was done in Rome could be in "copies" or "Rome." It's fun to think about how the experiences that Italy provided are reflected so directly in the works.

Stephanie Herdrich: And it evolves over time, too. The earliest artists were mostly interested in the art and the history. They were thinking about what it means to be American, what our young nation looks like, and what they could learn from the older nation's history and landscape.

For Thomas Cole, the effect of man on the landscape and the ruins of great civilizations were of considerable interest. What was his attitude towards nature at a time when the American landscape was still relatively undeveloped and unspoiled? Cole studied the ruins; he did plein air sketches, which was still a novel concept for American artists. When he returned to the United States, he translated his experiences in Italy into a vision of the American scenery. In the exhibition Thomas Cole's Journey, on view downstairs, you can see the way Cole incorporates ideas about empire—its rise and fall—into his art. This had a tremendous influence on later American painters.

Will Fenstermaker: Right, he kind of allegorizes it.

Stephanie Herdrich: And that's partly from visiting England and seeing great landscape paintings by Turner and Constable, but also from seeing Rome and the Italian countryside. For Cole, the appeal of Italy was this remarkable combination of art, nature, culture, and history. Cole inspired the American artists who came after him to paint the Italian landscape and explore some less familiar places.

In one section of the exhibition are paintings of the countryside, including Lake Avernus near Naples, Sicily, and the hill towns of Tuscany. You'll see several charming landscape paintings by Elihu Vedder—who was from a generation later than Cole—in the show, which represent locales off the beaten path.

Will Fenstermaker: I love his series of paintings depicting Aesop's fable of the miller, his son, and their donkey.

Stephanie Herdrich: I think they are wonderful. The story behind it is that Vedder had left Italy and was traveling in Spain. Apparently, he was so homesick for Italy that he decided to paint these pictures of the classic fable, dividing it into nine scenes set in medieval Tuscany.

Elihu Vedder (American, 1836–1923). The Fable of the Miller, His Son, and the Donkey Nos. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9. Oil on canvas, all 6 1/2 x 10 3/4 in. (16.5 x 27.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gifts of John V. and Enza Tomassi Kiskis, 1992 (1992.205.1–9)

Will Fenstermaker: Where was he in Spain? Because this could almost be Andalusia.

Stephanie Herdrich: He was in Cádiz, but maybe the sunlight and the architecture of Spain was making him long for Italy. This is an unusual subject for Vedder, who tends to be known for his mystical and symbolic scenes. We have studies for eight of the nine scenes. I thought it was a wonderful moment to show the drawings alongside the paintings.

What's interesting to notice, too, is that Vedder was thinking about the passage of time throughout the day. The earliest scene seems to be morning, and then the sun gets brighter, the shadows get longer, the sun sets, and it ends at night.

Will Fenstermaker: Oh wow, it becomes like a modernist novel about this poor donkey.

Stephanie Herdrich: I know, it's so awful! The poor donkey suffers such a tragic fate at the hands of the foolish miller and his son. But I love the anecdotal details, which give a Romantic view of picturesque Tuscany, the characteristic architecture of the hill towns, and the attractive Italian figures in their medieval dress.

Will Fenstermaker: These allegorical paintings by Vedder are very different from some of his other paintings in the exhibition. At another point in the show, a wall text mentions an Italian school he came in contact with. Did lots of American artists take up with Italian schools?

Stephanie Herdrich: Well, it varies depending on the artist. Vedder associated with a group of Italian painters known as the Macchiaioli.

Will Fenstermaker: Who were they?

Stephanie Herdrich: They were a group of painters based in Florence who were basically anti-academic, moving away from the traditional methods of studying in the Academy, and were really interested in painting outdoors and capturing effects of light. They gathered at the Caffè Michelangelo in Florence to discuss ideas about the creation of their art and politics.

Vedder found them at a moment when their message resonated with him. He had been in Paris studying at the Academy and he was just not inspired. So he headed to Italy, where he met these painters, and hung out with them out in the countryside, painting. What could be more pleasant? [laughter]

Will Fenstermaker: One imagines with a bottle of Chianti.

Stephanie Herdrich: That's the idea you get. He's sort of fleeing from Paris and the structure of the French Academy.

Elihu Vedder (American, 1836–1923). Cypress and Poppies (detail), ca. 1880–90. Oil on canvas, 9 3/4 x 20 in. (24.8 x 50.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Iola Stetson Haverstick, 1982 (1982.441)

Will Fenstermaker: Is Vedder's Cypress and Poppies an example of when an artist would sketch outdoors in watercolor and then return to the studio to make an oil?

Stephanie Herdrich: No, Cypress and Poppies was likely painted outdoors directly from nature. When we talk about something being academic, we're talking about a tradition of careful study, usually drawing first and then painting. Vedder was moving away from that tradition. There's an openness to his brushwork, a sense of spontaneity if you look at the flowers, those dabs of brushstroke. This parallels in some sense what the Impressionists were doing, but it's a different, darker palette.

Will Fenstermaker: Were the Impressionists particularly interested in Italy?

Stephanie Herdrich: When I think of the Impressionists and Italy, I think of Monet's paintings of Venice—particularly because of his connection to John Singer Sargent, who is well represented in this show. Monet and Sargent had friends in common in Venice, who hosted them at their Palazzo on the Grand Canal. They weren't there at the same time, but they had similar interests. The city of Venice lends itself well to studying the effects of light on water, those shimmering qualities that captivated so many artists.

By the mid- to the late nineteenth century, as painting outdoors and Impressionism became more mainstream, more American painters headed to Venice. After the Civil War, American art was becoming increasingly cosmopolitan. Sargent was so completely cosmopolitan; he considered himself American, but he spent much of his life in Europe. Vedder became so attached to Italy he ended up settling there for the rest of his life. I would say that Sargent and Vedder were less invested in American politics than someone like Cole. By the 1880s and '90s, there was a different idea about what it means to make an "American" art more than . . .

Will Fenstermaker: . . . Just art? But there is a kind of politics in that cosmopolitanism, too, because of this conception of the United States as a melting pot.

Stephanie Herdrich: That's true. And with the Gilded Age there was increasing industrialization, commercialism, much more wealth concentrated among fewer people . . .

Will Fenstermaker: And the establishment of art museums like The Met.

George Inness (American, 1825–1894). Olive Trees at Tivoli, 1873. Gouache, watercolor, and graphite on blue wove paper with colored fibers, 7 x 12 3/8 in. (17.8 x 31.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Morris K. Jesup Fund, 1989 (1989.287)

Stephanie Herdrich: Right. In that context, then, what does the experience of Italy mean to American art? Sargent, in particular, was making works in Italy that appealed to an international audience. George Inness, for example, went to Italy sponsored by a dealer for a couple of years to get ideas for his pictures. These Italian subjects were popular with American collectors.

Will Fenstermaker: There are artists in the show through whom you can track a more personal development. Vedder was one, and Sargent too. There's a sketch here that Sargent made when he was fourteen, and you can almost trace his career from there.

Right: John Singer Sargent (American, 1856–1925). Night, 1870. Graphite on off-white wove paper, 10 3/4 x 15 1/4 in. (27.3 x 38.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Francis Ormond, 1950 (50.130.143z)

Stephanie Herdrich: Yes, Sargent was born in Italy to American parents and had a life long love of Italy. Scholars like to say that Sargent was peripatetic, that he moved around so much that he had no home, he was from everywhere—but for me, he's really connected to Italy. It's where he became an artist. He was determined to be an artist from a young age; his mother helped him cultivate his eye and his drawing skills. She was an amateur artist and she required all of her children to finish at least one sketch every day. So Sargent was really prolific, drawing all the time, and she was making sure he saw every museum, every monument, and every site. During his formative years, he was surrounded by Italian art and culture, and so here he is at fourteen, copying Michelangelo's sculpture in Florence.

Will Fenstermaker: That's a brave thing to do.

Stephanie Herdrich: I know, but he's good. There are some awkward parts where you can see that he was having difficulty with the anatomy, but he was only fourteen years old! He was developing his skills and really absorbing everything he saw.

John Singer Sargent (American, 1856–1925). The Marriage of Cana (from scrapbook), ca. 1872–74. Graphite and watercolor on off-white wove paper, 9 1/2 x 14 7/8 in. (24.1 x 37.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Francis Ormond, 1950 (50.130.154b)

I'm also obsessed with his scrapbook, which he bought right after arriving in Paris in 1874, when he was eighteen. It's kind of his own personal museum. It includes copies of Italian art, photos of works of art that interested him, clippings from magazines, commercial photographs of Spain and of Italy, drawings, all kinds of things. . . . Some of the drawings are pasted in, and then he continued the drawing on the page, so we know that he assembled it himself. It's the first time this scrapbook has ever been shown at The Met.

Will Fenstermaker: How interesting! So copies such as these are a part of the academic tradition that inspired so many of these artists to travel to Italy?

Left: J. Carroll Beckwith (American, 1852–1917). The Veronese Print, ca. 1890. Black chalk and pastel on grey wove paper, 10 7/8 x 8 1/8 in. (27.6 x 20.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Janos Scholz, 1949 (49.167)

Stephanie Herdrich: Copying the Old Masters was a time-honored tradition. But even within this installation, you can see the different ways that artists incorporated copies into their art and internalized the lessons and meaning. So there's a straight copy as an academic exercise. For example, Michelangelo was celebrated as a genius at representing the human figure, so artists copied Michelangelo to learn about anatomy. But then, in this drawing by J. Carroll Beckwith, for example, there's something more complicated. Beckwith uses a print by Veronese of the Madonna surrounded by saints as the background for his portrait drawing. For Beckwith, it's less about studying Veronese than it is about showing his knowledge. He's aiming at a kind of symbolism for this beautiful young woman, as if she's a modern Madonna. The reference to Veronese is a sign of his culture, his cosmopolitanism, his education.

I love the contrast of this Sargent drawing after Cellini's Perseus to Julian Alden Weir's copy of a painting by Botticelli. Here is Weir as a young student, copying Italian art at the Louvre in Paris, and it's a bit labored. In contrast, Sargent's graphite sketch of Perseus is very quick and spontaneous. He is more interested in the dark, the light, and the shadows than the statue itself.

Left: John Singer Sargent (American, 1856–1925). Loggia dei Lanzi, Florence, 1902–1908. Graphite on off-white wove paper, 11 3/8 x 9 in. (28.9 x 22.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Francis Ormond, 1950 (50.130.131). Right: Julian Alden Weir (American, 1852–1919). Copy after Botticelli. Watercolor on paper, 9 9/16 x 6 3/8 in. (24.3 x 16.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Coe Kerr Gallery, 1982 (1982.372)

Will Fenstermaker: Even though this isn't an exhibition of Sargent, he seems to support a lot of the different themes here.

Stephanie Herdrich: His interest in and attachment to Italy are reflections of the greater culture and the taste for Italy in the period. Where he probably ends up being most influential is in his watercolors of Venice. They secured his reputation as one of the great watercolorists of all time. He had such a passion for Venice. He said his Venetian watercolors were his most precious works. You can feel his enthusiasm and passion in them.

Left: John Singer Sargent (American, 1856–1925). Venetian Passageway, ca. 1905. Watercolor, gouache, and graphite on white wove paper, 21 3/16 x 14 1/2 in. (53.8 x 36.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Francis Ormond, 1950 (50.130.77)

Will Fenstermaker: Why are his Venetian watercolors so canonical?

Stephanie Herdrich: So many of the themes that he's interested in—light on stone, architecture, and water—are represented in his Venetian works. But also look at the fluidity of his painting—the way the pigment becomes the water. Sargent's technique is so expressive and the works seem so spontaneous, even though they're actually very carefully prepared and premeditated. They embody the idea of sprezzatura, of studied carelessness. He makes it look effortless, like he just did it in ten minutes! When you look closely at Sargent's Venetian Passageway, you see that this work has a very measured geometry to it, but he's obliterating the evidence of his effort in the way he paints.

By 1900, Sargent was at the height of his success as a portraitist, but he grew tired of being in the studio all the time. He retreated to Italy. There's an amusing letter where he tells a friend, essentially, "I've gone to Italy to avoid painting portraits." Italy represents an escape for him, a respite. Between 1898 and 1913, he visited Venice almost every year. (He would also travel to other spots in Italy.) For him, Italy was an escape from the drudgery of the portrait studio and working on commission. There, he was unfettered, painting what he loved, surrounded by family and friends in this wonderful, congenial environment. It was a holiday for him.

I love this trio of works—the Whistler and the two Sargents, which are just these quiet, off-the-beaten-path views of Venice. Venice, by this time, was already pretty touristy, but here there's this sense of quietness. Both artists are deliberately getting away from the bustling, crowded parts of the city, and representing what they see as the essence of Venice.

Installation view with Venice, 1880–82, and Venetian Passageway, ca. 1905, by John Singer Sargent (left and center), and Note in Pink and Brown, ca. 1880, by James McNeill Whistler (right)

Will Fenstermaker: Sargent also appears at the other end the exhibition, with some watercolors from Rome and Milan, which you've placed next to these beautiful architectural studies by Julian Clarence Levi. I don't know anything about Levi, but they're two of my favorite paintings in the show. They just pop off the wall.

Stephanie Herdrich: That's the fun part of doing shows like this, searching through the collection. I had never heard of Levi, and when I was looking through our databases we only had black-and-white photos of his works. Levi was trained as an architect at Columbia University and in Paris, and you can see his meticulous observation of the architectural details.

Then there's also this beautiful sense of atmosphere and light, and the reflection on the marble. He was picking iconic architectural spaces that are also eclectic. This chapel in Palermo was known for its blend of architectural styles over history. It's such a complex space, but he really gets the depth, the spatial sense. There's a clarity to it, despite how complicated it is.

These two paintings are just fascinating records of his experience and his travel, rendered with incredible architectural draftsmanship. He died in 1971 and had a lengthy obituary in the New York Times, which has this wonderful description of his apartment, filled with this lifetime of experience and collecting. Of a moment long ago.

Installation view with Interior of Church, Sienna, 1902, and Capella Palatina, Palermo, 1903, by Julian Clarence Levi (left), and Loggia, Villa Giulia, Rome, ca. 1907, and Tiepolo Ceiling, Milan, ca. 1898–1900, by John Singer Sargent (right)

Will Fenstermaker: Seen next to the Sargents, you can contrast the ways both artists focused on architectural elements. Sargent seems to isolate a detail or two, and gesture toward the rest, whereas Levi meticulously details the entire space.

Stephanie Herdrich: The painting styles couldn't be more different. Sargent's watercolor of the Loggia at the Villa Guilia in Rome may have been abandoned before it was finished and it was probably never exhibited in the artist's lifetime. It's more of a spontaneous sketch of an architectural detail that captured his attention—the light and shadow beneath the columns and the arcade. In the other painting, Sargent was looking at a space that's very decorated and complicated, a Tiepolo ceiling in this completely Baroque hall. Somehow, he captures the Baroque splendor of it, but in a way that's so general—and far less detailed than the works by Levi.

Will Fenstermaker: Vaguely Baroque is such an oxymoron!

Stephanie Herdrich: Exactly! At this time, Sargent was preparing to paint his own mural decorations in Boston—the largest one being at the Public Library—so perhaps here he was thinking more about an overall decorative impression of the space.

Will Fenstermaker: American Painters in Italy covers just over a century. The earliest work, by Copley, is from 1774, and the latest works are by Prendergast in about 1912 and Sargent in 1913. Was there some change that caused Italy to leave the American imagination?

Maurice Brazil Prendergast (American, 1858–1924). Rialto Bridge (Covered Bridge, Venice), ca. 1911–12. Watercolor and graphite on off-white wove paper, 15 3/8 x 22 1/4 in. (39.1 x 56.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Lesley and Emma Sheafer Collection, Bequest of Emma A. Sheafer, 1973 (1974.356.1 recto)

Stephanie Herdrich: With the outbreak of World War I, artists weren't able to travel as much. That's what kept Sargent away. During a visit to Florida in 1917, he wrote about how much he missed Italy. He visited a friend who was building an Italian Renaissance-style villa near Miami. He wrote this wonderful letter saying, "I can't tear myself away, it's just like Italy and reminds me of all of these places that I'll probably never see again." There's a real nostalgia for Italy and a sense that he's cut off from these beloved places. But, of course, this is a moment when the art world is changing dramatically as well.

Will Fenstermaker: How much of our understanding of Italy today—and maybe even tourism in general—can be traced back to the influence the country had on American art?

Stephanie Herdrich: I really do think it's cumulative. Many artists had a sense that they must see Italy, that you somehow weren't completely educated unless you had experienced the culture and the history. As tourism became much more popular and accessible, you have a similar sense of accumulating culture through visiting these places. In the twentieth century, cinema continued this tradition. Think about movies like Federico Fellini's La Dolce Vita and Roman Holiday with Audrey Hepburn and Gregory Peck.

Some of the things that captured the imagination of American painters in the nineteenth century are the same things that capture our imagination today as tourists. There is still this sense that Italy is a special place that encapsulates great history, art, and culture. I think that the allure of Italy and la dolce vita still resonates today.

Note: This interview has been edited for publication.

Related Content

American Painters in Italy: From Copley to Sargent is on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through June 17, 2018.

Read more Curator Conversations on Now at The Met.