Oumy Mbaye and Mouhamet Traoré are both PhD students at University Cheikh Anta Diop in Dakar, Senegal. Part of the history department, they both trained in archaeology, focusing on Senegal’s ancient history and its wealth of archeological sites. As research fellows in The Met's Department of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas for four months, they became integral members of the curatorial team responsible for the exhibition Sahel: Art and Empires on the Shores of the Sahara. They have now returned to Dakar, where they are finishing their doctoral dissertations. Here they share thoughts about their time in New York and their experiences at The Met.

Oumy Mbaye

I am a PhD student in archaeology at the Cheikh Anta Diop University in Dakar, Senegal. On December 6, 2019, I began my fellowship at The Met. This adventure started for me in 2017 when Alisa LaGamma, chair of The Met's Department of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas, came to Senegal as part of a four-year long process of researching the exhibition Sahel: Art and Empires on the Shores of the Sahara. Following her visit, we made arrangements for me to join her curatorial team in the department, and last winter I moved from Senegal to New York City for four months. I arrived with the cold, but icy winds didn't affect my enthusiasm for our hosts' hospitality. I was greatly impressed by this American metropolis, with its massive buildings, amusement parks, subways, and restaurants. However, I was most excited by the prospects of the exhibition.

Sahel, which opened in January, is an important showcase for African populations living in New York, especially those who were born in the United States and who often have less direct access to this history. Through its emphasis on preserving and promoting African heritage, the exhibition invites communities to discover the extraordinary cultural, architectural, intellectual, and artistic wealth of medieval Africa.

Preparing the exhibition was an incredible task. Each of the two hundred objects—including wood sculptures, ceramics, manuscripts, musical instruments, and textiles—were meticulously checked by the Museum's conservators. The exhibition opens with a massive megalith from the eighth or ninth century, over two meters high and weighing more than four tons. It took several hours to maneuver this large laterite conglomerate in place. Two other ancient works in stone complete the entrance to the exhibition, including the oldest object in the installation: a sculpted female body dating back to around 2000 B.C.

Take a virtual tour of the exhibition Sahel: Art and Empires on the Shores of the Sahara.

Throughout the galleries, works of beautiful creativity are displayed in a wide range of media, including the gold Rao pectoral (one of Senegal's national treasures) and terracotta figures from the Middle Niger Delta. Covered with pustules or snake motifs, some figures testify to healing or magical practices. Others intrigue me with their positions of humility, submission, struggle, or ease.

Textiles produced in the Sahel over a thousand-year period—from an eighth-century tunic in dyed wool excavated in present-day Niger, to a nineteenth-century talismanic tunic covered with leopard claws, antelope horns, and leather bundles that contain suras from the Qu'ran—highlight fashion and magical-religious motifs. Eight Qu'ranic tablets show how the religion was adapted in the Sahel; one eighteenth-century tablet expresses religious syncretism.

Architecture in the region is represented as well, highlighting the regional technique of banco. A video shows the annual renovation of the celebrated Great Mosque of Jenne, which is constructed with banco walls reinforced with wood.

During Sahel's installation, Oumy Mbaye watches excerpts from the documentary Living Memory: Six Sketches of Mali Today, directed by Susan Vogel, depicting the annual renovation of the Great Mosque of Jenne.

Several historical chronicles (Tarikh al Fattash and Tarikh al-Sudan) highlight the artistic and intellectual production developed in the medieval Sahelian cities Awdaghost, Timbuktu, Kumbi-Saleh, Walata, and Gao. The French conquest of Segu in 1890 is represented by manuscripts by scholar and military leader El-Hajj 'Omar Tal, in which he develops many themes, notably the jihad.

The central axis of the exhibition showcases Soninke, Middle Niger, Dogon, and Bamana equestrian figures spanning several centuries, which The Met's technicians installed with great care. This cavalcade ends with a collection of magnificent Bamana figures from the eighteenth through twentieth century. Some of these figures represent accomplished women wearing insignias of power such as ornate bonnets and sheathed knives. These representations of strong women command my attention because they highlight the decisive role that women play in the stability and cohesion of African society; traditional African societies were matriarchal and matrilineal (the inheritance of property, family names, and titles was based on one's mother's lineage) before slave trade and colonialism introduced patriarchal lineage. In one of the traditional societies in Senegal, the Lébous, which is my own heritage, it is the women who make decisions.

Installation view of Sahel

African history is filled with accounts of powerful female leaders. For example, in 1855, French colonizers faced resistance from the Walo queen Ndatté Yalla Mbodj. Women also led the Zulu migrations in nineteenth-century southern Africa and formed their own squads in Emperor Shaka the Great's terrifying army. And of course, we cannot neglect the political power of the seventh-century queen Dihya of Mauritania and the legendary princess Yennenga of Burkina Faso.

While these figures are not represented in Sahel, the Bamana sculptures represent the accomplishments of our mothers. The seats on which they sit, the hunting hats some wear, the daggers along their left arms—these are just a few symbols of the central place that women had in political and religious decision making.

The status of cultural heritage in the Sahel has changed considerably in recent decades, thanks in part to UNESCO's involvement in the region. Indeed, the Sahel's cultural heritage—particularly its emphasis on humanity's relationship to nature—deserves special recognition, not only because of its current state of fragility. The Sahel's rituals, traditions, and cultural landscapes maintain their diversity in the face of globalization, and intercultural dialogue encourages respect for such ways of life. The training I received during this fellowship will facilitate my access to employment at international or Senegalese cultural organizations. It will also allow me, in return, to further the training of young cultural professionals and to contribute to the development of Africa's extraordinary culture.

Mouhamet Traoré

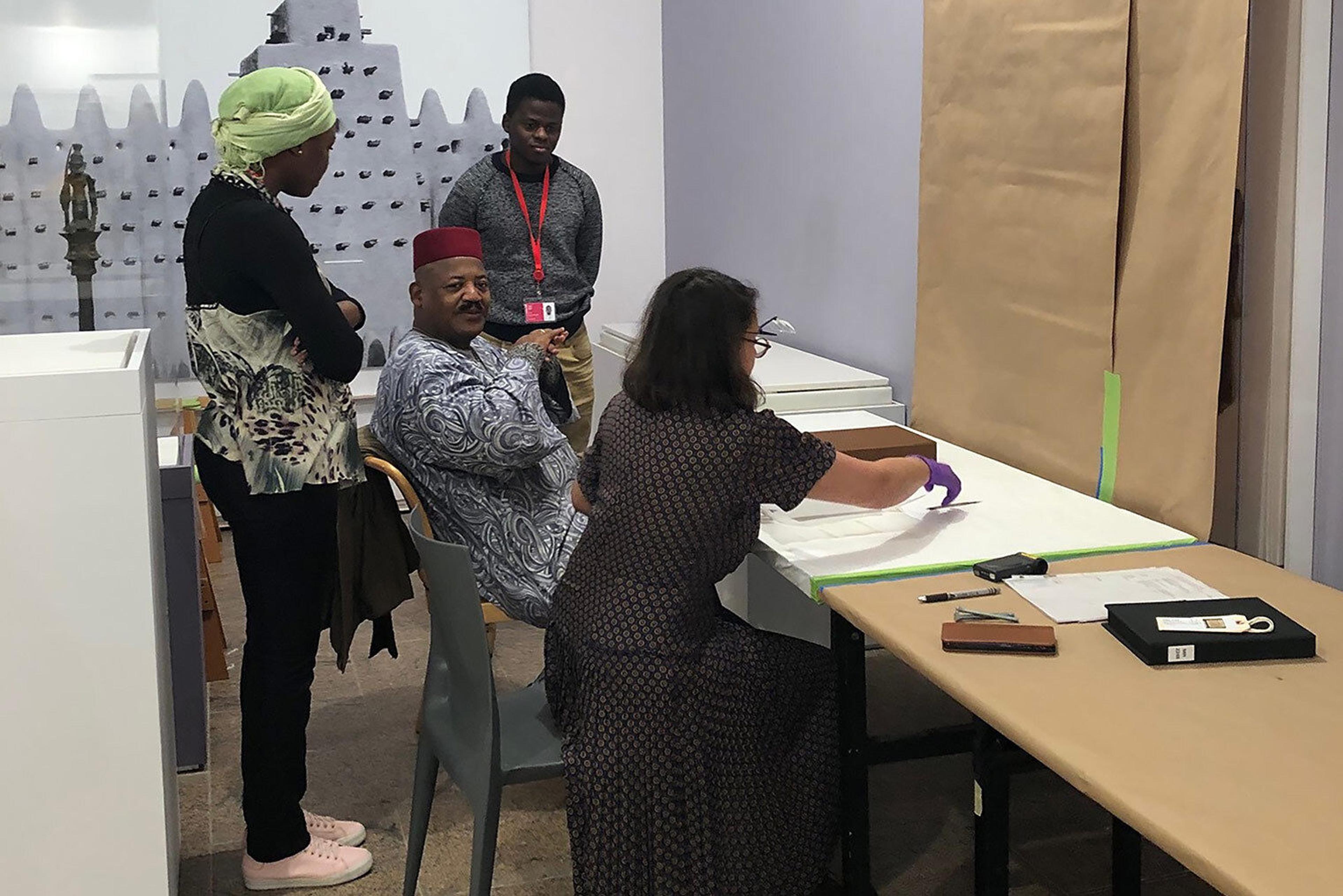

Oumy Mbaye (left) and Mouhamet Traoré (center) speak with Abdel Kader Haidara, custodian of the Mamma Haidara Memorial Library in Timbuktu, Mali, and Marina Ruiz-Molina, a paper conservator at The Met.

I am a PhD student in archaeology at the Cheikh Anta Diop University in Dakar, Senegal. My research is oriented toward the history of sub-Saharan Africa, and it was while conducting archaeological fieldwork that I met Alisa LaGamma, chair of The Met's Department of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas. She subsequently offered me the wonderful opportunity to participate in The Met's Sahel exhibition through a research fellowship.

This fellowship at The Met and my stay in New York were revolutionary for my university, particularly the history department with which I am affiliated. American scholarship is considered very prestigious in Senegal, and with this trip to New York, I was taking a major step in my career. Moreover, I was honored to work on an exhibition where I would represent Senegal and the other countries of the Sahel. This experience transformed the course of my academic life, which was mainly focused on archaeological excavations and documentation. Indeed, for the first time, I found myself working in one of the world's greatest museums, rediscovering the archaeological objects that I used to see on sites or in the laboratory. In this new dimension, these objects are ambassadors of the countries they represent and are treated with enormous respect.

Mouhamet Traoré stands before the Qur'anic boards and marabout tablet he translated.

One of the best things I experienced during the fellowship was the opportunity to meet researchers and professionals from other major institutions, such as the French Bibliothèque nationale de France and Musée du Quai Branly, and from Sahelian countries, such as the Mamma Haidara Library in Mali, and the Musée National de Nouakchott in Mauritania, among other lenders to the exhibition. These meetings provided a framework for discussion, exchange, and learning.

When the exhibition opened, I was pleased to see how fascinated the visitors were by African art and culture. I felt proud to answer the questions some of them asked me about the objects in the exhibition. For example, one visitor asked me about the role of wooden tablets that children use to study. Others asked me about the Bamana boubou worn by Mande hunters called donso. As a member of this group of donso, I felt great pride seeing these visitors discover these objects and answering questions about them. I saw how African art was appreciated by others.

Installation view of Sahel

Beyond working in the gallery, my mission was to reach out to the communities of people from the Sahel now living in New York so they might be aware of the exhibition promoting their cultural heritage. In our outreach mission, we met with the Senegalese Association of America, the Malian Association of New York, and the Senegalese Consulate, who were enthusiastic about this exhibition. They said it allowed them to discover historical art objects that are preserved in their countries of origin, and that it is a great opportunity for children born in New York to discover Sahelian culture.

New York is an incredibly diverse city, and through this experience, I came to understand why the famous French singer Grand Corps Malade, in his song "Enfant de la ville," described it as "an urban dictionary." Almost all the world's food is in New York, as are many of the world’s languages. Once, I was surprised to hear the Fulani language of Futa-Jalon in the subway station. This description of the "urban dictionary," which I've heard since my childhood, took concrete form.

This experience is very precious in my life and my career as a cultural worker. Through it, I met different inhabitants of Sahelian countries, and thanks to these meetings and exchanges, I was able to establish a network that goes beyond my home country of Senegal. Integrating Sahelian countries is a pressing concern for archaeologists and other cultural industries, and part of the genius of the Sahel exhibition is that in bringing together objects from different countries, it also brings together their people.