Today, the multidisciplinary artist Ana Mendieta is remembered for a richly realized oeuvre that fused Afro-Cuban religious traditions with feminist thought and questions of ecology. Her “earth-body” artworks famously used the natural world and her own body as powerful mediums of expression, interrogating humanity's relationship to the land and the cosmos.

Born in Havana, Cuba, on November 18, 1948, Mendieta moved to the United States as part of Operation Peter Pan, which resettled children during the Cuban Revolution. After a tumultuous and peripatetic childhood, she eventually landed in Iowa. She completed her MFA at the University of Iowa before moving to New York City.

This illuminating documentary, released two years after Mendieta’s untimely death in 1985, draws together a wide range of family members and friends—artists, writers, curators—to reflect on the artist’s brief but extraordinary career. We spoke with the film’s directors, Nereida Garcia-Ferraz and Kate Horsfield, via email.

What first drew you to Ana Mendieta’s work? Did you ever meet her?

Nereida Garcia-Ferraz:

I met Ana when she visited Chicago in 1980. I was studying at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and the school invited Ana to come by. She called me because we had many friends in common from the arts community in New York. She asked me on the phone if I had a car. I did, so I picked her up that evening and we went for a drive. We connected immediately. She told me how she had gone to a place in Iowa when she came from Cuba. That evening she spoke about how she used to create trouble at the orphanage. She hated being there.

The following night she invited me to the place she was staying for dinner and to see her artwork. I remember she made chiles rellenos and we drank wine. After, she projected images of her work—it was so powerful. She was maybe only 5 feet tall, but that evening I got the impression she was too tall. I had never seen work like that. Strong. So female. Direct and powerful. Nature, body, and Cuba were all there. Her voice explaining how she worked on her silhouette stayed with me for a long time.

Ana became a friend. She was generous and resilient. We were both very interested in what was going on in Cuba, and going to Cuba was not an easy thing. It was nearly impossible to travel there if you were Cuban unless you traveled with a group, but the exile community perceived it as treason to travel back. We both felt that it was important to connect to Cuba. We both had grandmothers on the island. Ana took a group of American artists there.

Left: Ana Mendieta (American (born Cuba), 1948–1985). Labyrinth of Venus (Amategram Series), 1981. Gouache and acrylic on bark paper, 16 x 11 5/8 in. (40.6 x 29.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Mrs. Fernand Leval and Robert Miller Gallery Inc. Gifts, 1983 (1983.502.3). © The Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection, LLC, courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co., New York / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Right: Ana Mendieta (American (born Cuba), 1948–1985). Vivification of the Flesh (Amategram Series), 1981. Gouache and acrylic on bark paper, 24 3/4 x 17 in. (62.9 x 43.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Mrs. Fernand Leval and Robert Miller Gallery Inc. Gifts, 1983 (1983.502.1). © The Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection, LLC, courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co., New York / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Kate Horsfield:

I found Mendieta’s work to be an enormously powerful and moving example of how artists can use inner struggle to inform their work and choose appropriate materials and processes to empower it. After being separated from her family and homeland at an early age, Mendieta developed her extraordinary vision based upon her personal history of displacement. By placing the female body—the outline of her body—back into the elements of earth, she utilized the emerging feminist theories of binding the personal to the political.

My partner, Lyn Blumenthal, and I had met her a few times at artists Leon Golub and Nancy Spero’s loft. I also met her a few times at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

This film was released in the wake of tragedy, two years after Mendieta’s death in September 1985. When did you decide to make the film?

Garcia-Ferraz:

The news of her death took all of us by surprise. Ana was very vital—that was one of the first things anyone noticed when they met her. I had seen her last in Chicago or New York; she had married Carl Andre. I could not attend her wedding but she was really happy. She had just been invited to travel to Rome with the Prix de Rome and she was super happy living there. So it all came as a shock when we read about her death, especially under those circumstances.

I had just won a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, and in November 1985 I traveled to Cuba to research and paint. I remember having a dream of going to visit Las Escaleras de Jaruco to look for Ana’s sculptures. All the memories from her life were still so fresh among her family and friends. I felt like there was enough in me to make the documentary.

Horsfield:

Nereida Garcia-Ferraz and I were friends in Chicago at the time of Ana’s death and we very quickly decided to collaborate. We decided to focus the film exclusively on her vision as an artist and her history as a Cuban American brought to the United States as a child during the Cuban Revolution.

Garcia-Ferraz:

Kate Horsfield and her partner, Lyn, founded the Video Data Bank in Chicago at the School of the Art Institute. We decided to make the film right then, but we had no money. So Kate used her equipment and borrowed some from the VDB, and we went back to film in Cuba. Since we had no budget, we shot a trailer with Ana’s video works and began fundraising for production. At the same time, we started to interview friends from the art world in New York and in Havana.

You interviewed a wide cast of people for this film, from Mendieta’s sister, Raquel Mendieta Harrington, to artists and writers like Nancy Spero, Gerardo Mosquera, Jayne Cortez, John Perreault, and Juan Sánchez. How did you decide who to include?

Horsfield:

The people selected for interviews were family, known friends, supporters, and/or colleagues of Ana’s in both countries. Ana had completed many works in Cuba and was well regarded and admired by Cuban artists and intellectuals. Garcia-Ferraz, as a Cuban American artist herself, provided an essential link to many of the Cuban artists, poets, and others who spoke in the film; we had total access to family members and artist colleagues while filming in Cuba.

Garcia-Ferraz:

Ana was part of the feminist art community and of the young progressive Cuban communities in New York and Chicago. Everyone who knew her was a resource to reconstruct her career, her intelligence, and her work. Kate took care of the interviews in English and I did most of the interviews with the family and the Cuban friends. I traveled to Iowa to interview her mother and to Havana to interview her dear cousin Raquel Mendieta. Raquel was a professor of Cuban culture at the Instituto Superior de Arte and a great history teller. She opened her family albums and made her family in Cuba part of this project.

The film also includes photography by Dawoud Bey and Mary Beth Edelson. Can you speak about the use of photographs in this film?

Garcia-Ferraz:

The voices and images of the film came from Ana’s family and from her friends. Ana was highly organized and left many books and pages with notations and poems. Her sister Raquel was very helpful and shared all the materials with us. The photos we used were either from Ana or from the close friends we interviewed for the film. It was beautiful how all the interviews created a timeline of her life and work.

A still from the film Ana Mendieta: Fuego de Tierra (1987), featuring a photograph of the artist.

Horsfield:

The goal was to make a documentary that reflected Ana’s life, politics, and work as fully and accurately as possible. In the 1980s Ana was not well known outside of a small number of people, mostly artist admirers. There was very little documentation of her person or her work outside of footage she made of her artwork. We found only five minutes of video from Cuban TV. We centered the film on video interviews in New York City and Cuba and photos from family albums, and used Ana’s films from Cuba and her photographs. Almost no other sources of documentation were used with the exception of Mary Beth Edelson and Dawoud Bey’s photos, which we needed to complete the story.

Music also plays an important role in the film. Can you tell us a little bit more about what you selected and why?

Garcia-Ferraz:

Music has the power to evoke the spirit of a person or place and I wanted viewers to feel like they had known Ana. When I visited her in New York City she would play records of Cuban music. I also come from a family of musicians and most of my memories are usually associated with listening.

For the opening scenes I found a marvelous theme by Cuban composer Marta Valdés, “Canción para un amigo” (A Song For a Friend), and I wanted to introduce Ana’s work with the voice of Cuban singer Miriam Ramos. For Ana’s family stories and early memories, I found the perfect match with the early songs of Carlos Puebla about the optimism of the Cuban Revolution.

Heitor Villa-Lobos’s “Bachianas Brasileiras No. 5” was perfect for the background of Ana’s cave works filmed in Jaruco, Cuba, because of the dreamlike quality of the sound. The brilliant voice of Milton Nascimento fit because Ana had gone to one of his concerts while she was living in Rome and loved his compositions.

I chose the enchanting sounds of New York salsa with Ray Barretto as background for Ana’s time living and working in New York. I commissioned the Mexican composer Alejandro Velasco for the Iowa theme and he came back with a mix of electronic sounds from my selection. All of this magic was made possible by the wonderful video editing skills of Branda Miller.

Ana Mendieta’s work directly engaged with the environment. In this film, you shot in a variety of locations from New York to Cuba. How did those environments shape the making of the film? Do you have any memorable moments from those experiences?

Garcia-Ferraz:

When we filmed in Havana we went many times to the hills and caves of Jaruco outside the city. Nobody knew exactly where she worked. We guided ourselves at first from photographs and then found the caves with the help of Cuban artist José Bedia.

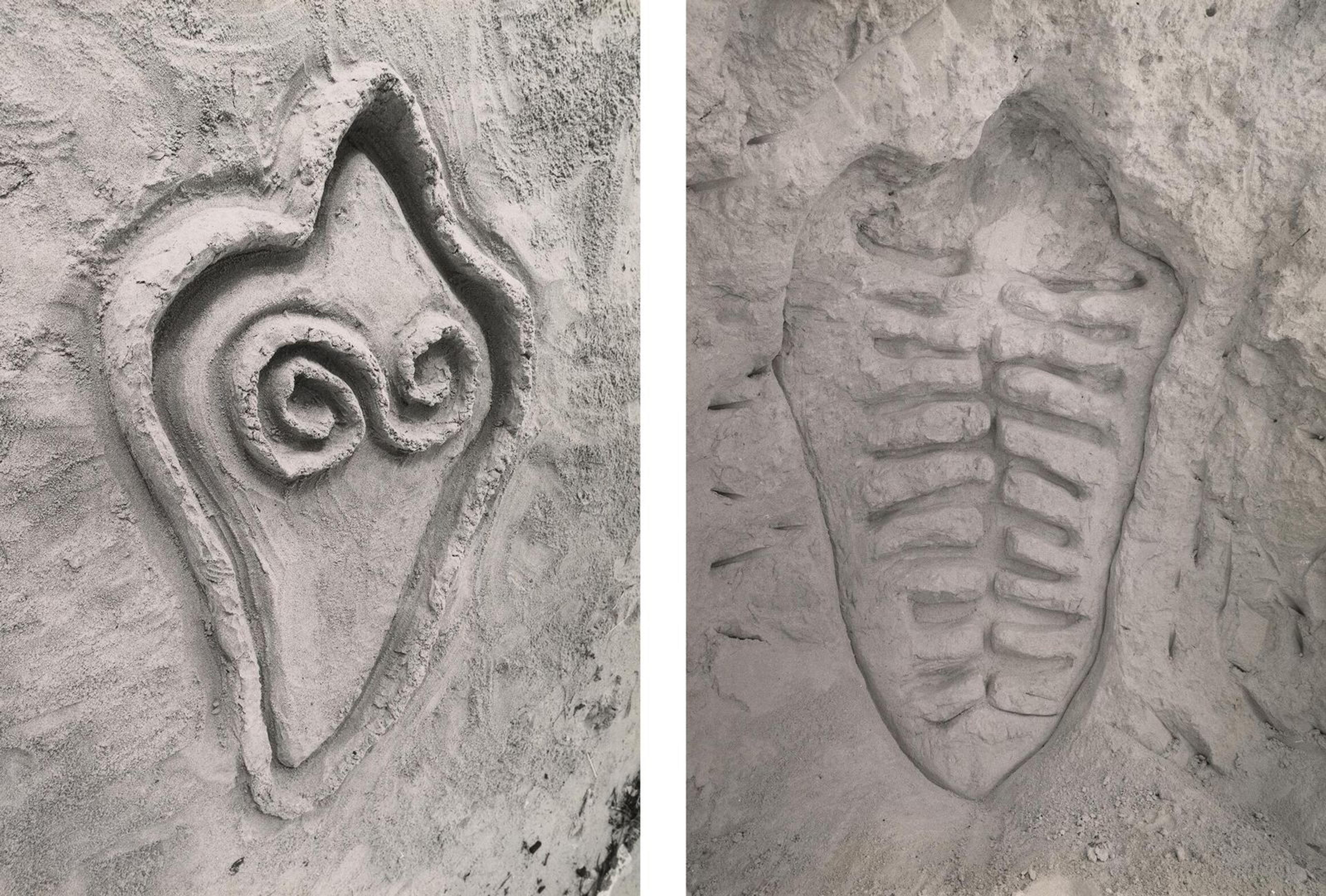

Left: Ana Mendieta (American (born Cuba), 1948–1985). Sandwomen, 1983. Gelatin silver print, 10 x 8 in. (25.4 x 20.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 1994 (1994.227.1). © The Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection, LLC, courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co., New York / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Right: Ana Mendieta (American (born Cuba), 1948–1985). Itiba Cahubaba (Esculturas Rupestres) [Old Mother Blood (Rupestrian Sculptures)], 1981. Gelatin silver print, 10 x 8 in. (25.4 x 20.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 1994 (1994.227.2). © The Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection, LLC, courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co., New York / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Horsfield:

We were fortunate to have access to the areas in Cuba where Ana made her environmental work. Ana had documented these pieces in film, and we went back to several of the original sites and filmed them again. The pieces are in remote areas and are subject to erosion and deterioration. Traveling with a guide to these sites felt similar to a religious mission to a holy site. It was deeply meaningful.

Garcia-Ferraz:

The Sony Betacam equipment was heavy and it made filming quite difficult. But we kept going back. The day we found the Black Venus behind a natural veil of foliage was magical. Nature had protected her work.

How did your own work as artists affect your approach? How does it affect the way you view the shape of an artist’s life?

Horsfield:

In the 1970s and early ’80s I was doing a feminist project of video interviews with artists (Agnes Martin, Lee Krasner, Elizabeth Murray, Joan Mitchell, etc.), and was busy searching for an understanding of individual women artists’ intentions, use of materials, expression of personal values, and aesthetics in their work.

I was fascinated by the emotive and political power in Ana’s personal narrative of separation from her family and homeland and her longing for return. This history became an emotional source for developing her work. By placing her body back into or upon the land, her performances and photography is a metaphorical return home. The personal narrative approaches the universal when she uses the primal elements of fire, wind, water, and erosion to outline her body and to reach out to others who share the loss of displacement. Each artist comes to different strategies and conclusions about the meaning and purpose of their work. Ana Mendieta’s version strikes me as what artists mean to do by using deeply embedded passions in their work to share with others.

Garcia-Ferraz:

We each brought different approaches to this video. For me, it was all linked by history, the complexity of our exile, and the need to speak about our complex realities. Ana came from a great Cuban family, deeply rooted in the island’s history. As artists, we shared the need to engage the viewers with the reality of being apart from our country from an early age.

We all worked nonstop to make this film a reality. Fuego de Tierra won Best Documentary at the Latino New York Film Festival in 1988 and also opened along with the retrospective of Ana’s work at the New Museum that same year.

The documentary feels vintage now but still brings a close portrait of a wonderful artist. After all these years, every time I see this work it brings back the joy of having known her. Making this documentary has brought Ana closer to the universe.

This interview has been edited for publication.

The film, Ana Mendieta: Fuego de Tierra, is distributed by Video Data Bank and Women Make Movies.