For Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage month, we’re highlighting five objects in The Met collection that point to the long and complex history of cultural exchange between the Western world and regions across Asia. This article speaks to our own research interests and personal experiences of cultural negotiation as Asian American art historians who work on artistic mobility between South Asia and Europe in the colonial period (seventeenth through twentieth centuries).

These five objects illustrate that Euro-American cultures have long been shaped by trade with Asia, as people and goods alike travelled thousands of miles along corridors of mercantile exchange. Contrary to the exclusionary logic of modern political borders that police the movement of people, cultural products move easily across borders.

Despite the West’s longstanding interest in the arts of Asia, racism and discrimination against Asian cultures were enshrined in several exclusionary immigration laws during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This specter of xenophobia still haunts Asian diasporic communities today. Consider, for instance, the eruption of violence and hate crimes against Asian Americans in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Growing racism, xenophobic discrimination, and violence against Asian diasporic communities call for an urgent reorientation of our understanding of Euro-American cultures and how these identities have been shaped. At a time when anti-Asian violence is on the rise in the United States, it’s all the more important to recognize that the contributions and influence of Asian and Pacific Islander cultures cannot be disentangled from American identity. The following transcultural objects from The Met collection highlight the impact of Asian artistic traditions on Western cultural practices, and assert the necessity of complicating the binary constructions of identity that exist today.

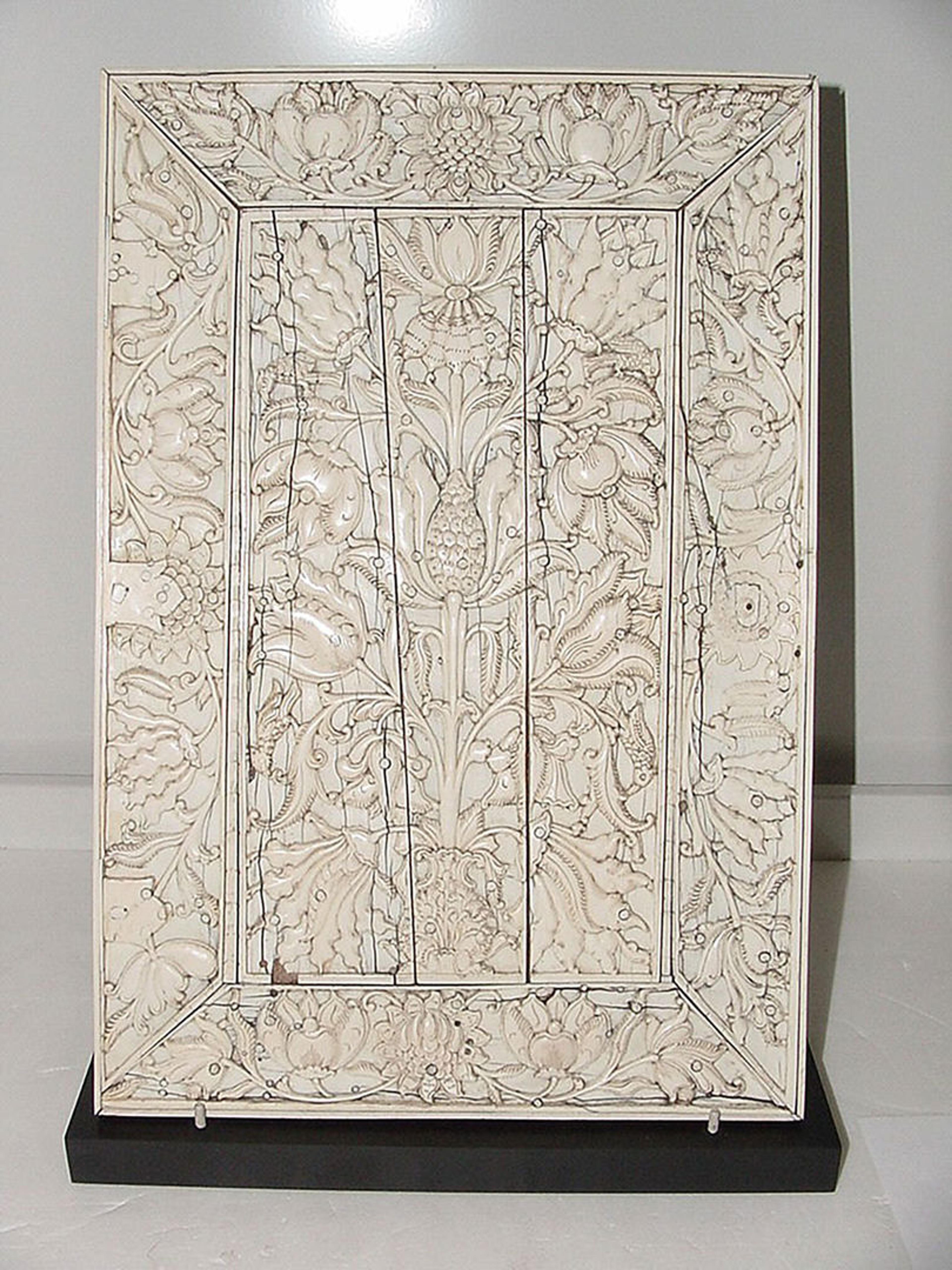

Ivory panel from a cabinet with flowers and birds, late 17th century. Attributed to India or Sri Lanka, Coromandel Coast. Ivory veneer over wood, 16 ¼ × 11 in. (41 × 27.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Cynthia Hazen Polsky and Leon B. Polsky Fund, 2006 (2006.259)

When European merchants settled in South and Southeast Asia during the seventeenth century, they often required furniture made from local materials since oak, walnut, and other European woods could not survive the humid climate. This ivory panel, likely created as an ornamental veneer, is carved with the dense floral and vegetal patterns that characterized the Southeastern Indian style. The veneer may have covered a cabinet used by Dutch settlers or been exported to the Netherlands, satisfying contemporaneous fascinations with South Asian ornamentation. These appropriations of foreign ornamental traditions compel us to reevaluate notions of European and American identity, which have long incorporated foreign cultures.

Katar, 17th century. India, Thanjavur; blade, European. Steel, 21 ¾ × 5 in. (55.2 × 12.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of George C. Stone, 1935 (36.25.1009)

Popular in southern India during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, katars were short daggers with handles perpendicular to the blades. Featuring the peacock Paravani, the sacred vehicle of the Hindu god Subrahmanya, this steel dagger celebrates the deity of war. While the hilt was cast and worked in South India, the blade was imported from northern Europe. This dagger, along with over one hundred other objects, was taken from the Thanjavur armory during a British raid in the nineteenth century. The transnational history of this object demonstrates that steel weaponry was crucial to forging connections between South Asia and Europe during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Plate, 1765–70. China, for export. Porcelain, 8 ½ in. (21.3 cm) diameter. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Mrs. Samuel Verplanck, 1942 (42.87.5)

European and colonial American demand for East Asian porcelain reached new heights in the eighteenth century. During this time, potters and merchants in porcelain-producing regions across China and Japan exported dishes, plates, and vases to eager buyers in Europe and the Americas.

This plate, which features red and pink floral motifs common in export porcelain, travelled to colonial New York during the second half of the eighteenth century. It was part of a large service that was passed down for generations, illustrating the sustained history of exchange between the United States and East Asia.

High chest of drawers. American, 1750–60. Maple, birch, white pine, 86 1/2 x 40 x 21 1/2 in. (219.7 x 101.6 x 54.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, 1940 (40.37.1)

By the mid-eighteenth century, a flourishing global trade between the United States, Europe, and Asia fueled middle-class and elite Americans’ desires to own fashionable luxury goods, such as Indian textiles and East Asian lacquerwork. New artistic techniques like “Japanning,” or the use of paint and gilded gesso, were developed to imitate the visual qualities of lacquer. This artistic innovation became particularly popular in coastal cities like Boston and Salem, which were closely aligned with the fashionable tastes of continental Europe.

This high chest of drawers uses Japanning to translate a popular form from colonial Massachusetts into the cosmopolitan visual language of Anglo-American Salem. It was passed down for generations in the Pickman family.

Palampore Tree of Life quilt, ca. 1815. United States, New England. Cotton, 8 ft. 6 in. × 8 ft. 6 in. (259.1 × 259.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Anonymous Gift and Friends of the American Wing Fund, 2014 (2014.263)

The above quilt incorporating a palampore is one example of the luxury commodities that were considered fashionable in the United States at the time. Palampores are a type of colorful hand-painted bed cover made in India specifically for export during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. This striking quilt brings together fabrics from both India (the center panel and inner borders) and Europe (the outer floral chintz borders). The center panel features a stylized “Tree of Life” design. The fabric’s T-shape is characteristic of New England quilts designed to fit around bedposts.

The circulation and consumption of objects from Asia were fundamental to the construction of a cosmopolitan American identity and, indeed, the ethos of modern American culture. These transcultural objects thus reveal a long, entangled history of the West’s relationship with the regions, cultures, and people of Asia.