In this striking picture, we witness the last moments of a man’s life.

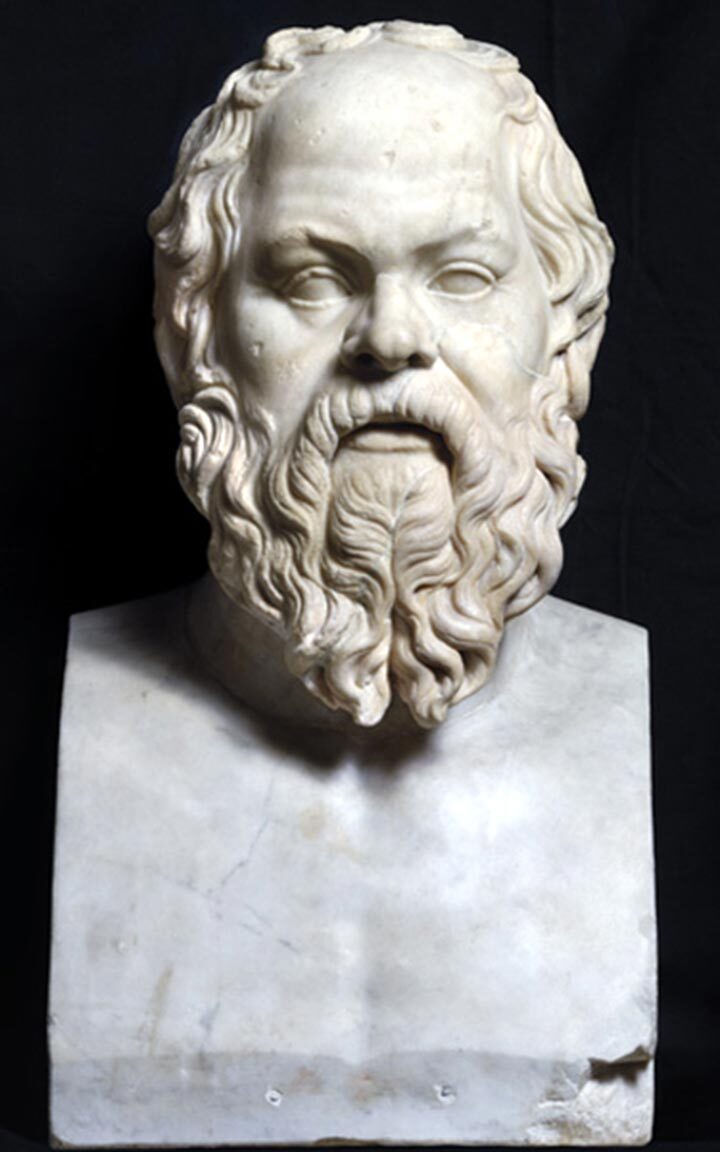

The man is the ancient Greek philosopher Socrates. Convicted by the Athenian courts of corrupting his followers with unorthodox teachings, he was offered the choice to renounce his beliefs or drink a cup of hemlock.

He chose the poison.

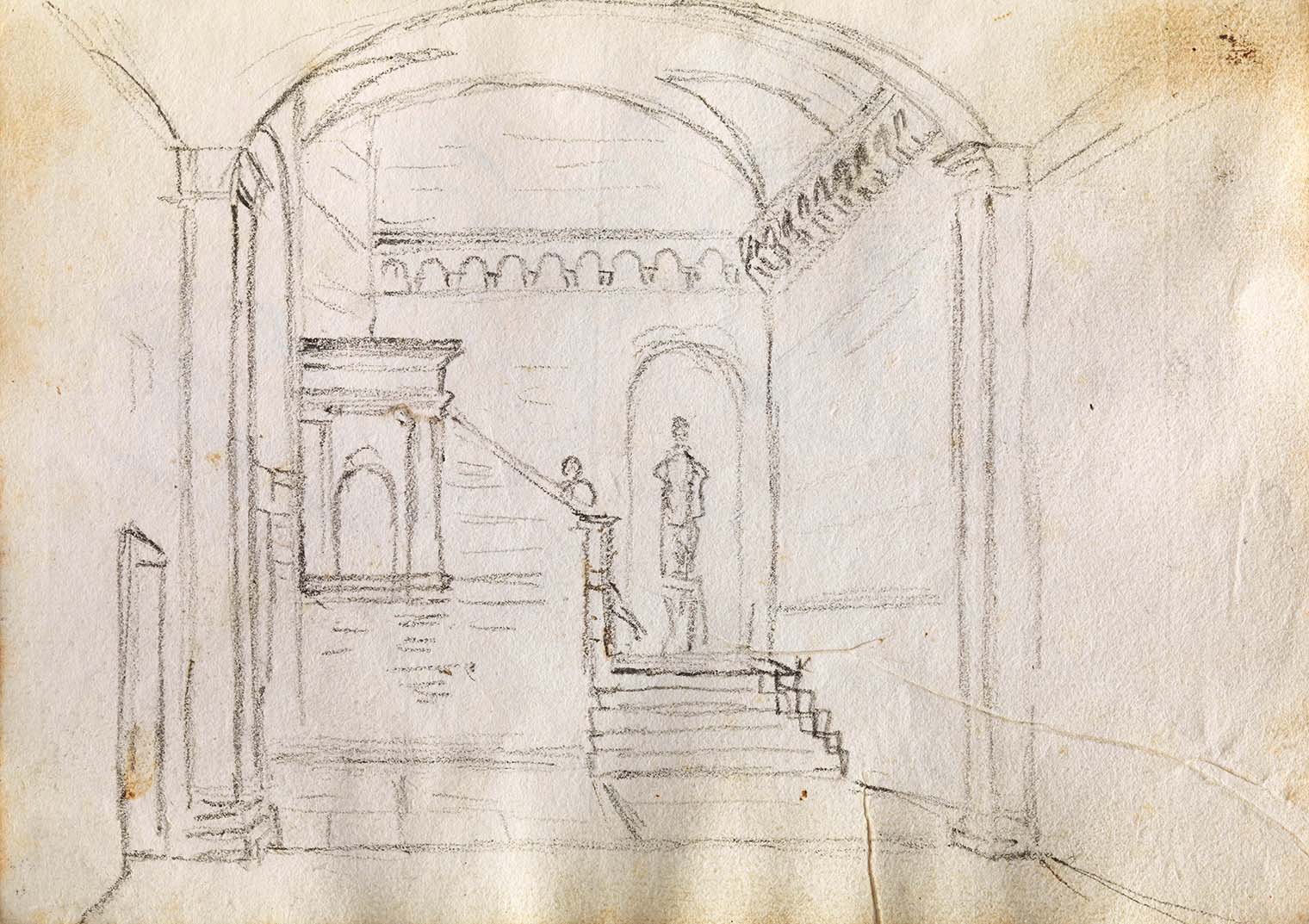

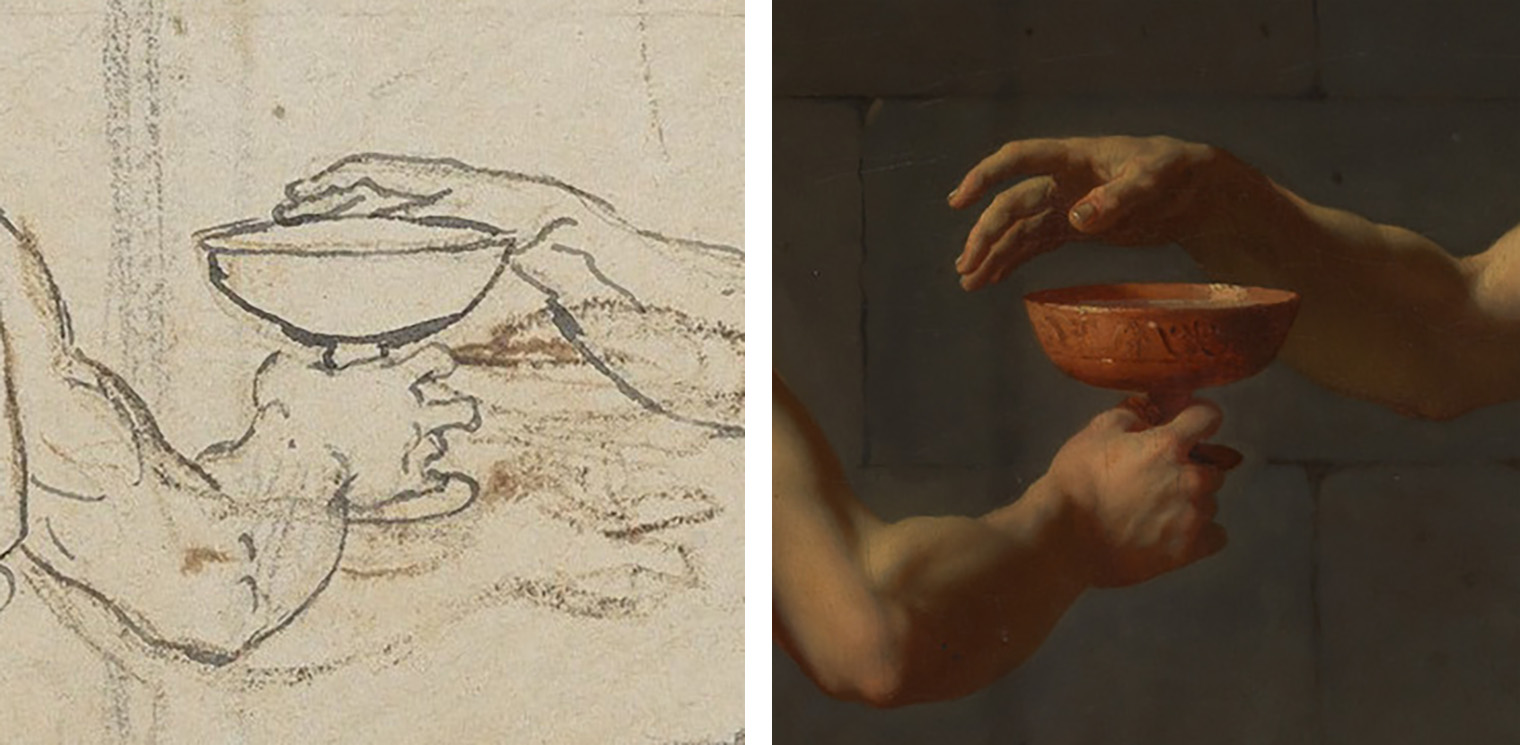

This painting by Jacques-Louis David (1748–1825), titled The Death of Socrates (1787), envisions the moment Socrates paused to address his disciples before drinking from the deadly cup. Completed on the eve of the French Revolution, it exemplifies David’s ability to address—and even galvanize—public sentiment through well-chosen episodes of ancient history.

David presents this wrenching tableau with perfect legibility, the fleeting moment frozen for the viewer’s unhurried contemplation.

Sunlight from an unseen source bathes the scene. The barred windows and cold stone walls identify the setting as a prison cell.

An open metal cuff rests on the stone floor.

In a visceral evocation of physical pain, Socrates’ ankle bears faint touches of red paint, as if the philosopher was just released from his shackles.

His expression, by contrast, is calm and full of resolve.

He gestures upward as he expounds, according to ancient texts, on his belief in the immortality of the soul.

Despite Socrates’ attempt to offer solace, the expressions of the men around him run the gamut.

Some of his followers listen attentively, while others appear gripped by anguish and despair.

A bearded figure sits by Socrates’ side and grasps his thigh, as if imploring him to reconsider.

The young man charged with handing Socrates the goblet of poison cannot bear to face him.

One figure seems to exist outside the drama: seated at the foot of the bed and facing away, his head bent and his hands folded in his lap.

He represents Socrates’ student Plato, who would have been in his 20s at the time of his teacher’s death and not present in the prison cell.

However, David here depicts Plato as an old man, the age he would have been when he described the scene in Phaedo, one of his “Dialogues.”

Plato’s role as storyteller is indicated by the writing implements David has placed at his feet: a scroll, a pen, and an inkwell.

David—who, as a painter of ancient history and legend, was another type of storyteller—credits his own role more subtly, by adding his initials to the stone block.

David’s close reading of Plato’s Phaedo is evident in the painting’s details.

The lyre on the bed, for instance—an unexpected object to find in prison—refers to a passage in which Socrates and his students debate whether the instrument and its music constitute an appropriate analogy for the human body and soul.

Though not an uncommon subject at the time, the determination with which David researched the story, delving deep into its complexity and nuance, gave his depiction a unique resonance.

In fact, long before he would raise brush to canvas, and even before he received this commission, David experimented on paper with ideas for staging the subject of Socrates’ death.