Watson Library is celebrating Women's History Month this year by sharing a small selection of books by and about American women artists who were active during the early to mid-twentieth century. These books have been acquired recently or had their catalog records revisited by staff hired for the project, “Research and Outreach: Increasing Representation of Indigenous American, Hispanic American, Asian American and Pacific Islander artists in The Met’s Thomas J. Watson Library,” funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities.

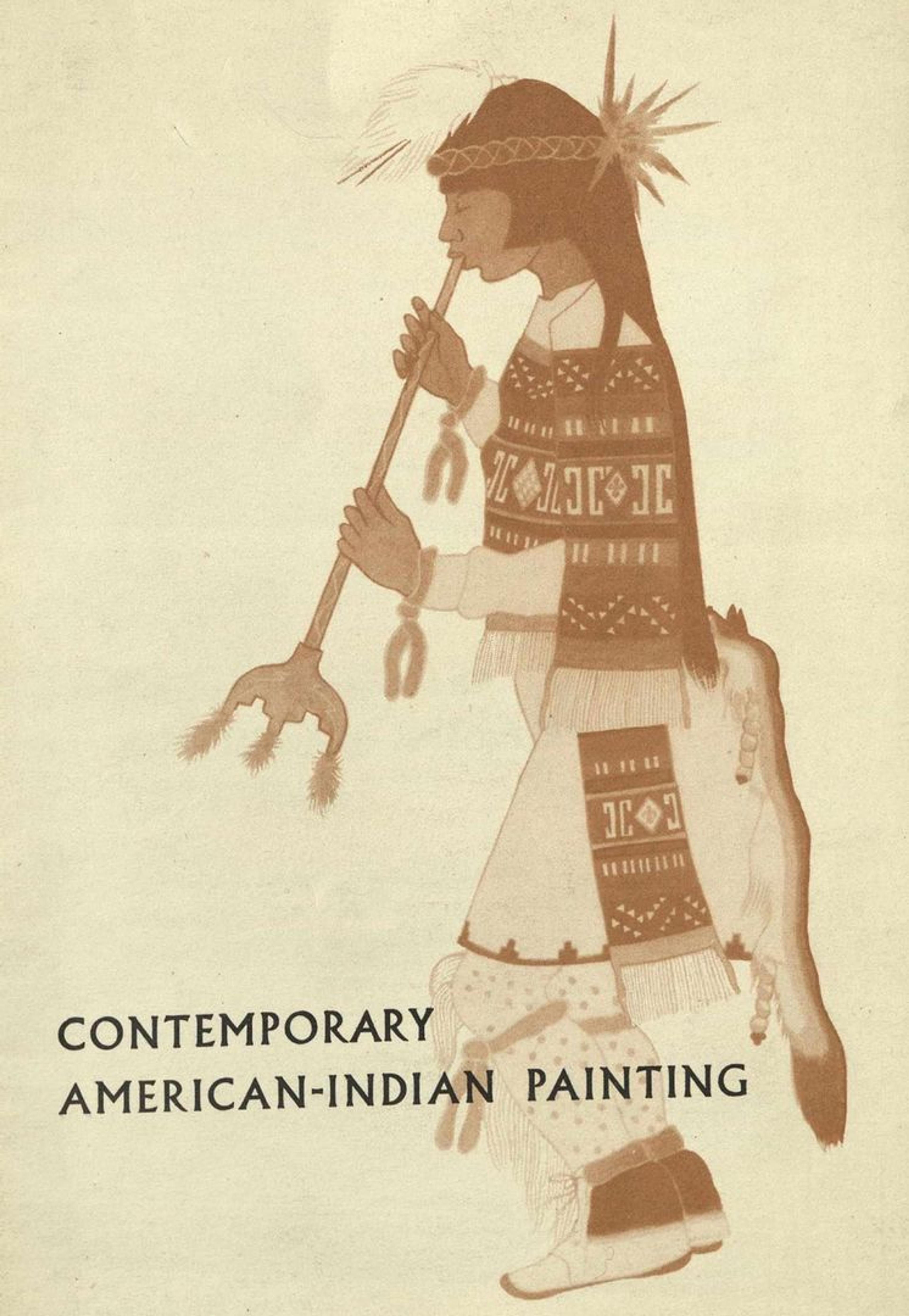

Contemporary American Indian Painting (Bradford, West Yorkshire, England: Regional College of Art Bradford, 1956)

As a cataloger on the NEH project, one of the most intriguing items I have encountered so far is a small pamphlet, Contemporary American Indian Painting. This publication documents one stop on a traveling exhibition organized by the College of Fine Arts of the University of Oklahoma under the auspices of the United States Information Service. The exhibition was sent to several European cities from 1955 to 1956 and this particular iteration was held at the Regional College of Art Bradford in England (now the Bradford School of Art at Bradford College) during February 1956. Of the thirty-seven artists represented, five were women, a figure that seemed surprisingly high to me for that time. Also unusual was that the text for this catalogue was written by a woman, Dorothy Dunn (1903–1992). Dunn established the Studio School at the Santa Fe Indian School in 1932, which she managed until 1937.

Another thematic inspiration for this post was the source of funding for our project: the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021. The ARP legislation can in some ways be seen as a contemporary version of the Relief Appropriation Act of 1935, which funded the ambitious and sweeping Depression-era public works program that included the Works Progress Administration (WPA). The WPA directly supported artists through the Federal Art Project, as well as through documentation projects similar to ours through the Historical Records Survey. I decided to highlight the careers of women artists who worked on WPA projects for this post. This selection process proved to be challenging since fewer women artists were employed than men, and even fewer have been the subject of monographs or included in catalogues of group exhibitions.

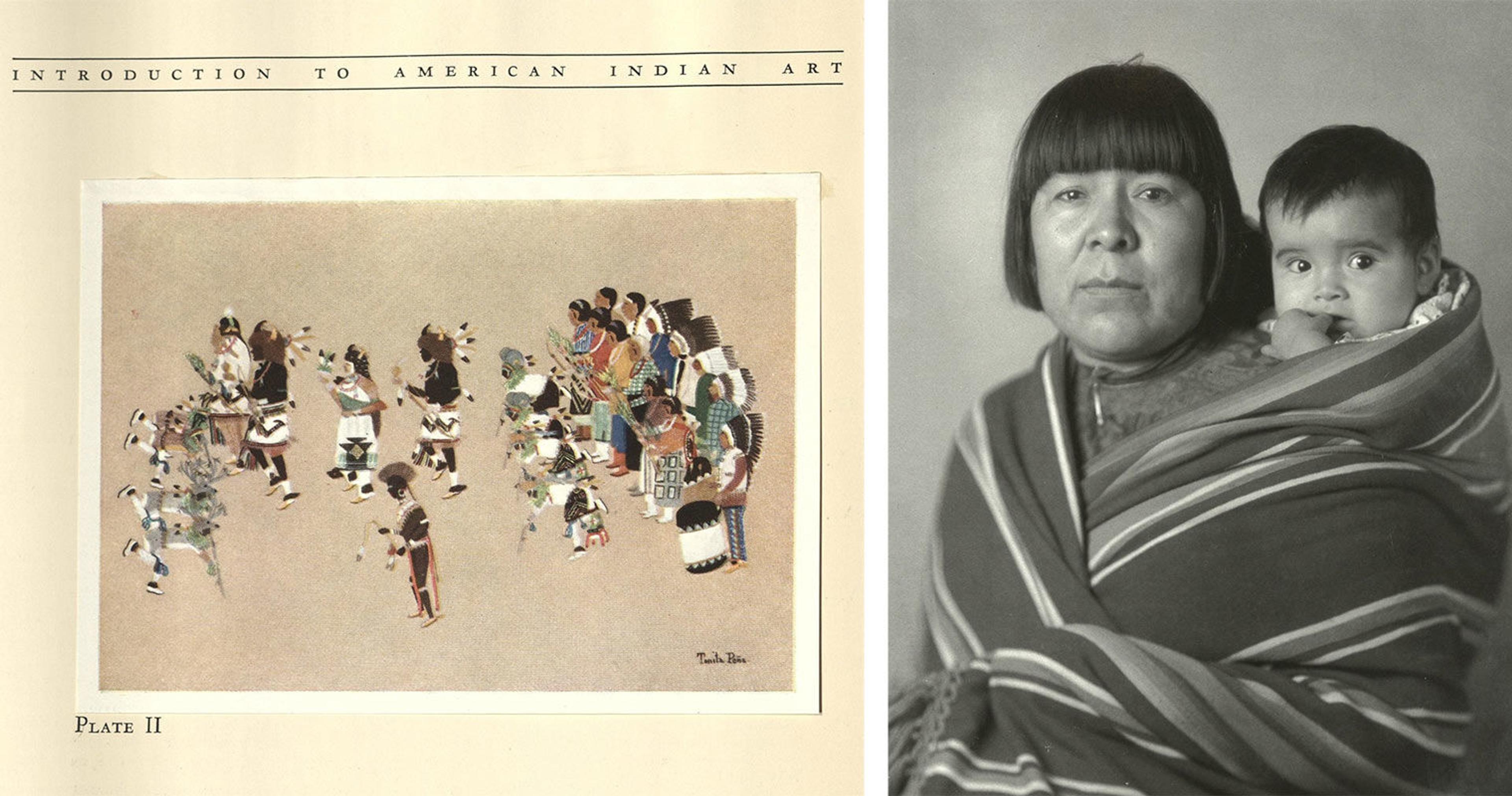

Left: Color reproduction of Hunting Dance, watercolor painting by Tonita Peña from first volume of exhibition catalogue Introduction to American Indian Art (New York: The Exposition of Indian Tribal Arts, Inc., 1931). Right: Reproduction of T. Harmon Pankhurst photograph of Tonita Peña and her infant son, Joe Hilario Herrera, from Jackson Rushing III, Generations in Modern Pueblo Painting: The Art of Tonita Peña and Joe Herrera (Norman, Oklahoma: Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art, 2018)

Tonita Peña (1893–1949), who was born Quah Ah at Tewa-speaking San Ildefonso Pueblo (in Tewa: Pʼohwhogeh Ówîngeh), helped to forge a path for other Native American women to become recognized as professional artists. Her grandmother, Toña Peña Vigil, had been a well-respected San Ildefonso Pueblo potter. After the death of her mother, Peña was sent to be raised by her aunt, Martina Vigil, and uncle, Florentino Montoya, also prominent pottery artists, but in the Cochiti Pueblo tradition. Peña had learned to paint and draw with Western materials at the San Ildefonso Public Day School. Her studies were cut short for marriages arranged by her aunt and uncle; by 1920, Peña had been widowed twice and become the mother of three children—including her son, Joe Hilario Herrera (1921–2001), who would go on to become a painter himself. She was left to support the family for a time primarily through the sale of her paintings to white patrons.

Peña was the only female Pueblo watercolorist included in the landmark Exposition of Indian Tribal Arts held at the Grand Central Art Galleries in New York in 1931. Her Eagle Dance was often reproduced in reviews and other publications about the show. Watson has copies of the two-part exhibition catalogue, Introduction to American-Indian Art, which includes plates of Peña’s Hunting Dance and Eagle Dance. Watson also holds copies of books about Peña and her family: Tonita Peña: Quah Ah, 1893–1949 and Generations in Modern Pueblo Painting: The Art of Tonita Peña and Joe Herrera.

During the 1930s, Peña taught at the Santa Fe Indian School, which received funding from the Public Works of Art Project, a short-lived predecessor to the WPA, where one of her students was Pablita Velarde.

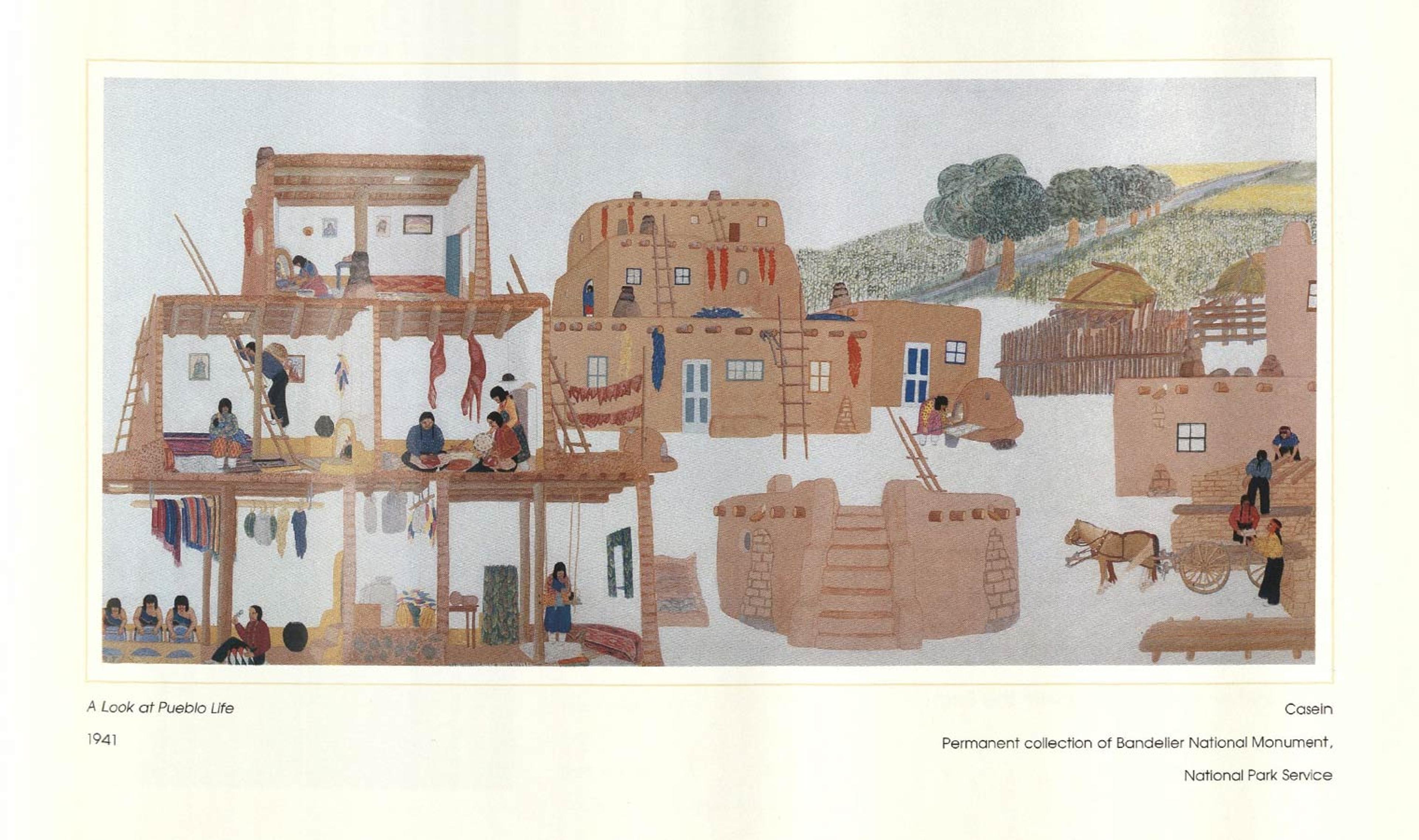

One of Velarde’s paintings, "A Look at Pueblo Life," for Bandelier National Monument, reproduced in Marcella J. Ruch, Pablita Velarde: Painting Her People (Santa Fe: New Mexico Magazine, 2001)

Pablita Velarde (1918–2006) was born Tse Tsan at Santa Clara Pueblo (in Tewa: Khaʼpʼoe Ówîngeh). After the death of their mother, Velarde and her sisters were sent to St. Catherine's Indian School in Santa Fe. At the age of fourteen, she became one of the first female students at the Studio School. Mentored by both Dorothy Dunn and Tonita Peña, she quickly became an accomplished painter. One of Velarde’s most important early commissions came from the National Parks Service, funded by a grant from the WPA. From 1937 to 1943, she produced an extensive series of murals for the Bandelier National Monument.

Velarde was among the artists (along with Tonita Peña and Joe Herrera) included in the catalogue for the James T. Bialac Native American Art Collection donated to the University of Oklahoma in 2010, The James T. Bialac Native American Art Collection: Selected Works. Both Velarde’s daughter, Helen Hardin (1943–1984), and granddaughter, Margarete Bagshaw (1964–2015) also became noted artists.

Watson also has other books about Velarde, including Pablita Velarde: Painting Her People (2001). As part of the project, Watson also recently acquired an autographed first edition of a book she wrote and illustrated, Old Father: The Story Teller (1960).

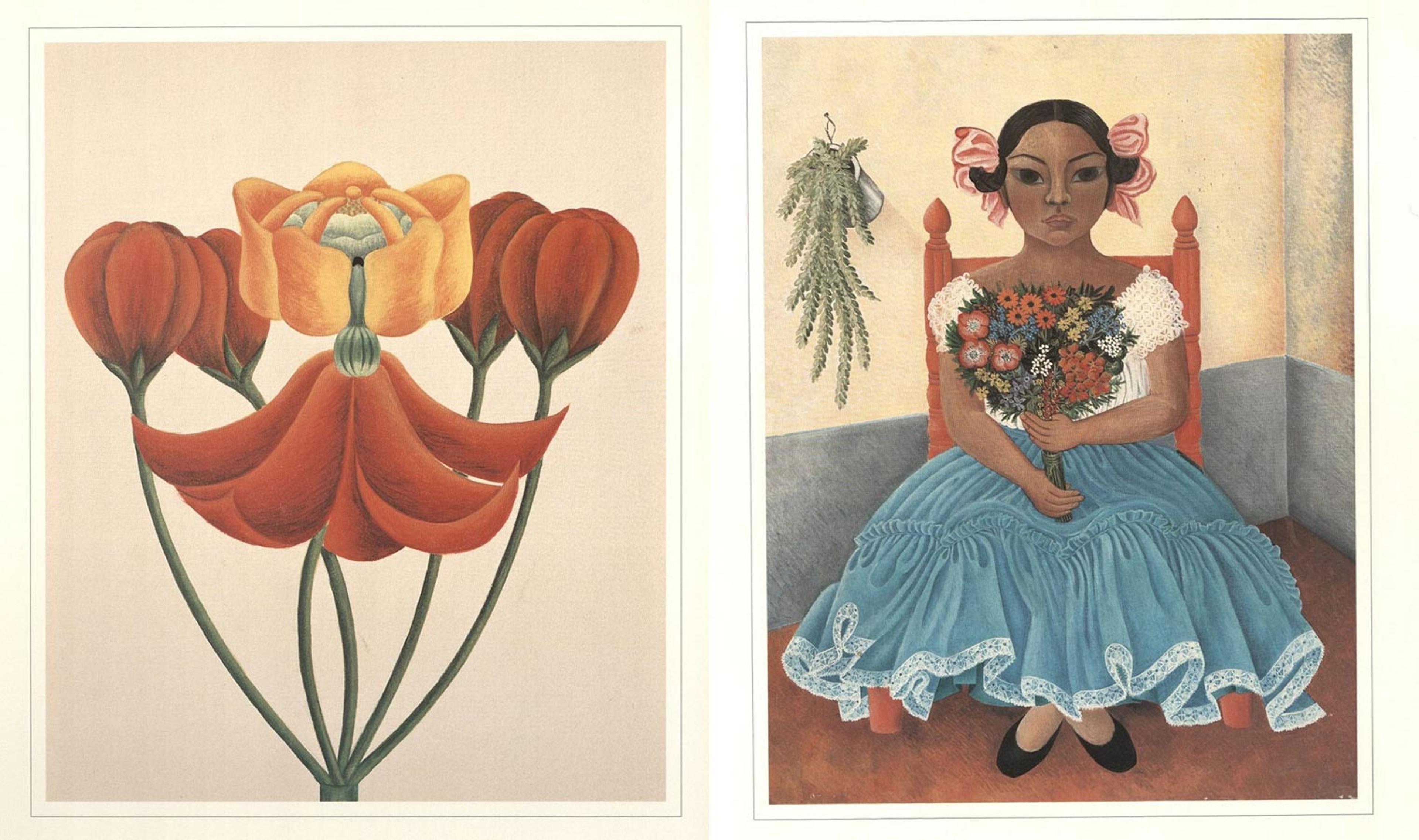

Two undated paintings by Rosa Rolanda, reproduced in Carlos Monsiváis. Rosa Covarrubias: Una Americana Que Amó México (Puebla, México: Universidad de las Américas Puebla, 2007)

Rosa Rolanda (1895–1970) was an American multidisciplinary artist who later settled in Mexico with her husband, Miguel Covarrubias (1904–1957). Although the couple collaborated on many projects, Rolanda’s own artistic output as a choreographer, dancer, designer, photographer, and painter has been overshadowed, until fairly recently, by that of her more famous husband.

Born Rosemonde Cowan in Azusa, California, to parents of Scottish and Mexican ancestry, she displayed an aptitude for the arts early on. She was a member of the Marion Morgan Dancers before striking out on her own. Adopting the surname Rolanda for her stage name, she became a featured dancer in a number of musicals and revues on Broadway, including the first Music Box Revue (1921). Rolanda helped Covarrubias to get the commission to design sets for the “Rancho Mexicano” number in the Garrick Gaieties (1925), which she choreographed.

Miguel and Rosa were married in 1930, at which point she changed her name to Rosa (sometimes Rose) Covarrubias. The couple traveled extensively both before and after they were married and went to Bali for their honeymoon. Initially spending nine months on the island, they immersed themselves in Balinese culture. They later published a book, The Island of Bali (1937), written by Miguel and featuring an album of Rolanda’s photographs. Her work was also represented in issues four and five (“Ameridinian Number”) of the journal DYN, published in 1943. Rolanda’s images also were used in Miguel’s Mexico South: Isthmus of Tehuantepec (1946).

On a trip to Mexico, Rolanda studied photography with Edward Weston and Tina Modotti. She also experimented with photograms during the 1920s and ’30s. The Davis Museum at Wellesley College has a sizable collection of Rosa’s works from this period, some of which were included in the 2019 exhibition, Art_Latin_America: Against the Survey. Although not directly funded by the WPA, Miguel received a commission to create a mural cycle, “Pageant of the Pacific,” for the Golden Gate International Exposition held on Treasure Island, a site developed by the Public Works Administration and WPA. Publicity photographs show Rolanda applying paint to one of the panels alongside Miguel.

By 1935, the couple had settled in Mexico City, where their home became an artistic and intellectual hub. Miguel and other Mexican artists, including Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, encouraged Rolanda to paint. Several of her paintings are in the Colección Blaisten in Mexico City. In 1952, Rolanda had a solo exhibition of her paintings at the Galería de Antonio Souza in Mexico City.

Watson Library also holds a biography of Miguel and Rolanda by Adriana Williams, Covarrubias (1994), as well as Rosa Covarrubias: Una Americana Que Amó México, a lavishly illustrated volume with many photographs from the Archivo Miguel Covarrubias, which are now held by the Universidad de las Américas Puebla (UDLAP).

Greg Robinson and Elena Tajima Creef, editors. Miné Okubo: Following Her Own Road (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2008)

Miné Okubo (1912–2001) was an American Nisei artist and writer whose promising career as a painter was disrupted by the events of World War II. Showing great resilience, she documented her experiences as a prisoner in Japanese American incarceration camps in her groundbreaking graphic memoir, Citizen 13660 (1946).

Born in Riverside, California, Okubo received a scholarship to study art at the University of California, Berkeley, where she earned a BA in art and an MA in art and anthropology. In 1938, she was awarded the Bertha Taussig Traveling Art Fellowship, which enabled her to visit Europe to continue her studies. She spent several months abroad, but after France and Great Britain declared war on Germany in 1939, Okubo was forced to return to the United States before the conclusion of her fellowship. Okubo found employment with the California Federal Art Project, working on printmaking and mural projects, which included demonstrating fresco technique for visitors to the Golden Gate International Exposition while Diego Rivera worked on a scaffold above, executing his final mural, Pan American Unity.

Following the issuing of Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942, Okubo and her family were forced to leave their homes. She and her youngest brother initially were sent to the Tanforan Assembly Center in San Bruno, California, but later were moved to the even more desolate Topaz Relocation Center in Delta, Utah. Demonstrating great resilience and courage, Okubo documented life in the camp through over two thousand sketches, organized an art school, and worked on two publications by and for the inmates of Topaz, the Topaz Times and the literary journal, Trek.

After her release from Topaz, Okubo moved to New York City, where she continued her career as a commercial artist for several years before returning to painting in 1951. She became an activist in the movement for restitution to Japanese American citizens unjustly incarcerated during the war, testifying before the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Citizens. A new edition of Citizen 13660 was published by the University of Washington Press in 1983 and won the American Book Award in 1984. Her work on Citizen 13660 is the subject of a current exhibition at the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles organized in honor of the seventy-fifth anniversary of its publication.

In addition to having copies of the first edition and reissue of Citizen 13660, Watson has the catalogue for a retrospective exhibition of her work, Miné Okubo: An American Experience, as well as a collection of essays about her work and life, Miné Okubo: Following Her Own Road, published by the University of Washington Press in 2008.