Read the show notes and illustrated transcript below.

Listen and subscribe to Immaterial on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, YouTube, Pandora, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Show Notes

Chisels and stones aside, for much of history, information was held in memory, shared orally through stories handed down from speaker to speaker. It wasn’t until the invention of paper—something we think of today as readily available—that communication and expression became easily recorded. First documented in China in the second century BCE, this new technology spread to India, the Middle East, and into Europe, allowing knowledge, thoughts and images to be transported throughout the globe and across time. But the history of paper was not nearly so democratic, because technology adoption never really is.

Paper holds meaning. It is a depository of so much that we value and cherish. For many of us, our first creative expressions were recorded with crayons on paper. This was long before we discovered the value of money, the significance of a marriage certificate, or the joy of getting lost in the pages of a book. With paper we can write, draw, paint, print, collage, rip, fold, bend, stack, pulp, photograph, communicate, mass-produce, and more.

Immaterial: Paper dives deep into The Met’s paper collection. In the Department of Drawings and Prints, we explore the significance of ephemera: baseball cards, diaries, and anything that the Museum collects which wasn’t originally intended to be a work of art. The Met’s ephemera curator Allison Rudnick explains why these treasures need to be preserved and tells us about some of her favorite objects in the collection. We meet writer, storyteller, and activist Tanzila “Taz” Ahmed, who tells us about the comic book collections she wishes her family could have brought with them when they immigrated to the United States from Bangladesh in the 1970s, and how she used paper ephemera to share her sense of humor with America’s Muslim community. Paper conservator Rachel Mustalish explains how she and her colleagues protect paper objects, from giving water baths to Dürer prints to halting the decay of a 1937 animation cel from Disney’s Snow White. Finally, ephemera historian and Met volunteer Nancy Rosin explains the real value of our messages of love, the valentine.

Paper is thin, it’s light, and—if it’s kept in the right conditions—it can last for a very, very long time. That’s important, because paper not only holds our memories of things past; the things we treasure enough to save reveal to us who we are. Listen for the whole story, and scroll through the gallery at the end of the page to take a closer look at the art mentioned in the episode.

Transcript

CAMILLE DUNGY: The Met has two million works of art, and one-and-a-half million of them are made of paper.

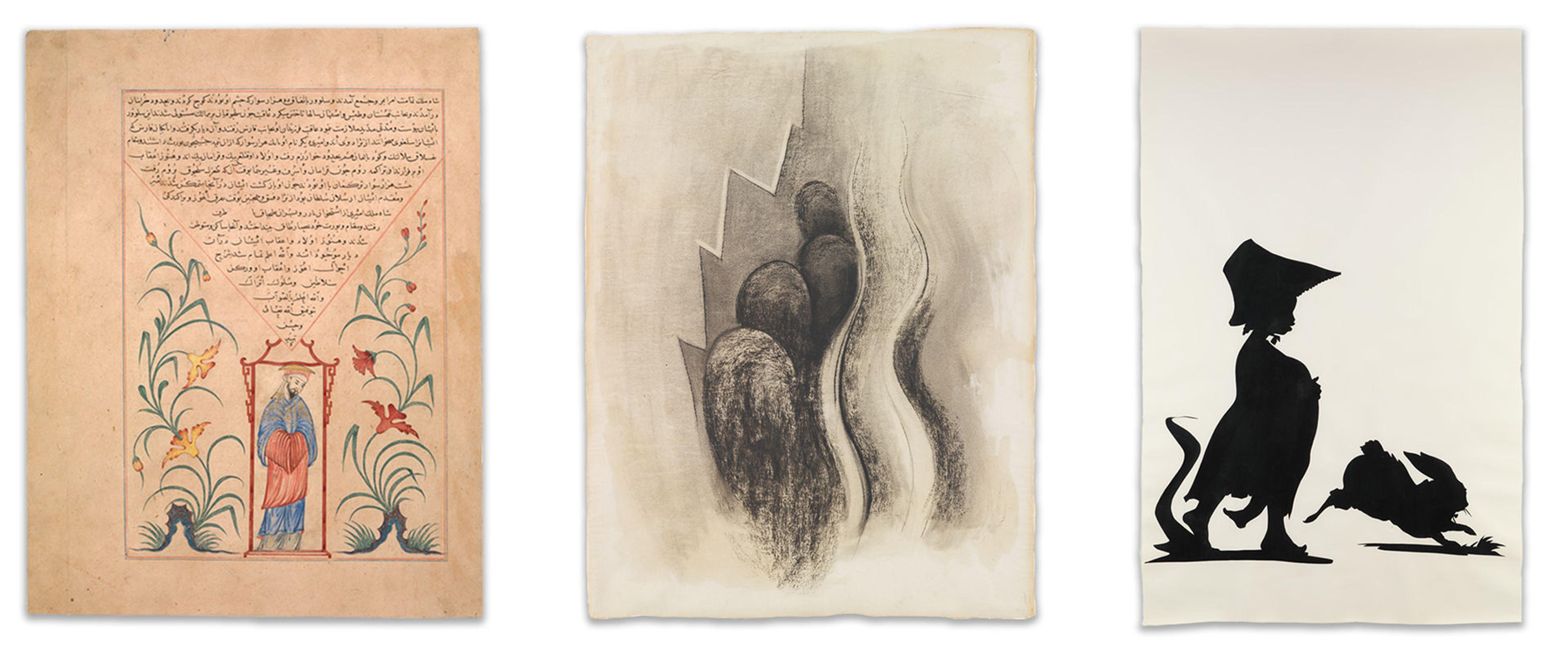

Few inventions have changed the world the way paper has. It’s been manipulated, colored, cut, bound into books, folded into origami, and more. From Persia’s fifteenth-century illuminated manuscripts to Andy Warhol’s famous screen prints, Georgia O’Keeffe’s expressive charcoal drawings, and Kara Walker’s cut-paper silhouettes—a walk through any of The Met’s galleries shows exactly how versatile paper really is.

From left to right: Hafiz-i Abru (Iranian, –1430). “Chinese Emperor Standing in Pavilion”, Folio from a Majma al-Tavarikh (Compendium of Histories) of Hafiz-i Abru, ca. 1425. Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper, Painting with Text Block: H.13 1/4 in. (33.7 cm); W. 9 in. (22.9 cm); Page: H. 16 1/2 in. (41.9 cm); W. 12 3/4 in. (32.4 cm); Mat: H. 19 1/4 in. (48.9 cm); W. 14 1/4 in. (36.2 cm); Frame: Ht. 21 1/4 in. (54 cm); W. 16 1/4 in. (41.3 cm); D. 1 1/2 in. (3.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of V. Everit Macy, 1929 (29.84); Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887–1986). Drawing XIII, 1915. Charcoal on paper, 24 3/8 x 18 1/2 in. (61.9 × 47 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1950 (50.236.2); Kara Walker (American, b. 1969). Fixin’, Pitted, Fished, Pitied, 1995. Cut and pasted painted paper on paper, 66 x 42 in. (167.6 x 106.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Francis Lathrop Fund, 2007 ( 2007.285a–d) © Kara Walker. Objects not to scale

DUNGY: But of all the different types of paper creations… I want to start with comic books.

TANZILA ‘TAZ’ AHMED: Every time I talk to a Bangladeshi, like everyone has stories about how their parents were into Archie comics.

DUNGY: Remember that redhead kid? He may be more familiar now from the television show Riverdale, but Archie’s innocent, small town adventures with Betty, Veronica, and Jughead started in 1941. The comic was beloved around the world... including by author, activist, and visual artist Taz Ahmed.

AHMED: They’re very halal. Just wholesome. Wholesome, good, non-problematic. There’s no, like, violence or sex happening in, like, these 1970s Archie comics. And there’s something so great about that.

DUNGY: Taz was a total bookworm as a kid. She grew up in Los Angeles and knew that visiting her mom’s family in Bangladesh meant she’d get to read Archie comics. It always felt like visiting old friends.

AHMED: I do remember my aunt’s collection. So she was still living with my Nana and Nani and she would keep all the stacks of the Archies, like, in a dresser. Probably had moth balls in it. And I had to pull them out. And Bangladesh is a very wet country. There’s monsoons every summer. All the pages... all the paper gets, like, moldy and gross and it’s really hard to preserve. Like, paper’s sacred in the country where it’s always wet and everything can, like, disintegrate.

DUNGY: Taz wondered why her mom didn’t have her own Archie collection in LA. Because it was clear that her mom loved the comics too.

AHMED: I think Jughead was my mom’s favorite character. Jughead being the rebellious one that you see eat all the time. And then I don’t know why, but I identified with that. I liked his crown. So I kind of felt like, ‘oh, if it’s mom’s favorite character, then it’s, like, my favorite character, too.’

DUNGY: So one day when Taz was around ten years old, she asked her mom, ‘where’s your Archie collection?’

AHMED: ‘Can I read them?’ And she said that she didn’t have them because she had to leave them behind. When I was that young, I didn’t realize that what she was saying was, ‘I left behind things cause we were in a civil war.’

DUNGY: In 1971, when the Bangladesh Liberation War began, many Bangladeshi nationals, like Taz’s mom and her family, were living in Pakistan.

AHMED: And so when things started escalating between east Pakistanis... so the west Pakistanis, all the Bengalis in Pakistan were being persecuted or being, you know, treated differently and they rounded up all the men and they sent them to a concentration camp.

DUNGY: Taz’s grandfather was one of these men.

AHMED: He wasn’t allowed to communicate with his family members. There’s a bunch of male... Bengali men there, think he was there for six months. He was able to send messages to my Nani through this cook that used to work for him. So now the cook was also working at the camp, so he was able to let my Nani know that he was okay.

He was there for like six months when he was released. Like the whole family had to get on a plane with everything they could carry and, like, go back to Bangladesh.

DUNGY: Everything they could carry… passports, clothing, whatever they could fit in a suitcase. And everything they couldn’t?

AHMED: They had to leave it behind. It’s just like this whole concept of, like, leaving with what you can pack in your bag. And, I think as a ten-year-old, I didn’t understand the weight of what it meant to leave things behind.

DUNGY: They left everything... including the Archie comics. Paper’s a funny thing. For most of us, it’s all too easy to accumulate. But at the same time it can be heartbreaking to let go.

AHMED: Paper’s like the first thing that you leave behind. Like, books are the first thing you leave. It’s too heavy to carry. Now It’s just kind of like, ‘wow that’s so intense, like, people having to flee their homes.’

I believe in Bangladesh, a million people died in that conflict. And it’s just such a great number. And I—when I was collecting stories of family in 2010, when I went by myself, there was just like all these stories that were coming up. And it’s just like, like really crazy to me that these were all connected to, like, me asking my mom about her Archie books.

But she was just so casual about it. She’s just like, ‘oh, I left it behind with my friends.’ I’m just like, well, let’s go back and get it. And she couldn’t really explain to me why she couldn’t go back and get it.

DUNGY: For something the wind could blow away, we ask paper to carry a heavy load. Marriage certificates record our unions; diaries keep our secrets; money makes the world go round. Paper holds our memories, our stories, our fears, and our desires.

But who makes the decision whether or not something made of paper is valuable enough to preserve?

Long term, paper is kind of a diva: light-sensitive, and fragile when exposed to the elements. Yet strong enough to hold iconic works like The Met’s massive woodcut print Arch of Honor by Albrecht Dürer and Hokusai’s “The Great Wave,” which have survived for centuries.

Value is in the eye of the beholder, and paper so often seems worth holding onto because it’s a vessel that carries the meaning we put on it.

From The Metropolitan Museum of Art: I’m Camille Dungy, and this is Immaterial, where we look at materials commonly used in making art and explore what the materials themselves can tell us.

[An ethereal shimmering sound fills the scene. We hear the words spoken distantly by an unfamiliar voice: “When I’m feeling them. What the sound and he texture and the way it rattles tells me is how the paper is, how short-fibered the paper is, and how the paper is going to, you know, behave.”]

—

DUNGY: I had an uncle who sent me greeting cards for nearly every occasion: Halloween, Thanksgiving, Christmas, Valentine’s Day, Easter, my birthday. For the few years he was alive after I had my daughter, I got cards from him on Mother’s Day, too. I keep all of these in a shoebox that I sometimes open just to see his signature on the brightly colored cards. Evidence of the care he took on each generic holiday to choose a message that somehow seemed perfectly suited to me. In a way, the paper we hold onto says a lot about us.

I thought about this after we asked people to share some of the things they couldn’t give up:

VARIOUS ANONYMOUS SPEAKERS: I collect paper dolls... Book pages... I collect postcards... Letters I received from girlfriends when I was a teenager... Invitations to weddings... World War II ration coupons... Little notes from my grandmother... There was a happy birthday note written on some toilet paper from my ex roommate. It made me particularly happy... I also have a box that has movie stubs from like Harry Potter and, like, Star Wars movies... The paper that I collect is basically a record of my life... And it also has a patina and age and tells a story... And those are like some of my most cherished things... a tremendous sense of connection with the past... I do it for me because I am so forgetful... And this small box of letters reminds me of how many people I’ve touched, how many people have touched me. Also, some people I really don’t want to talk to again.

DUNGY: It’s probably no surprise that a museum curator would have a bunch of collections of her own.

ALLISON RUDNICK: Oh, okay. I was a little old to be doing this, and I can’t believe I’m saying this out loud, but I did collect Pokémon cards. Stuffed animals, Beanie Babies, all the trends of the nineties. I’m a classic millennial.

DUNGY: Allison Rudnick is the ephemera curator in The Met’s Drawings and Prints Department. She’s speaking to us from the department’s study room, which is half academic library, half your eccentric grandfather’s home office…

RUDNICK: I could do this for months [laughs] [volume fades]

DUNGY: … green carpets, dark stained shelves, double-height carts stuffed with books, and albums on every table.

RUDNICK: You know, I remember people saying with Beanie Babies, for example, ‘these will be worth something one day, keep the tags on.’ And so of course there’s the aspect of, you know, monetary value tied to these things. But I definitely had an interest in having masses and groups of things in volume that I can’t really explain.

DUNGY: By definition, museums are interested in collecting groups of things to reveal, and sometimes increase, their value. But some museum holdings are more unexpected than others.

RUDNICK: From the museum standpoint, ephemera constitutes any object that was not intended to be a work of art. And in The Met’s collection, ephemera includes all sorts of printed material, typically on paper. And examples include trade cards, silhouettes, postcards, and oftentimes advertising materials included in the category, as well.

ADWOA GYIMAH-BREMPONG: OK, what am I looking at here?

RUDNICK: We are looking at a collection of postcards. We have thousands and thousands of postcards in The Met’s collection… [volume fades]

DUNGY: The Met’s Drawing and Prints collection contains more than 180,000 works. And ephemera makes up roughly thirty percent of it.

RUDNICK: It’s curious and really surprising to a lot of people that we have an enormous section devoted to objects that were not intended to be art. I could probably speak about this for days, but in short the value of these objects is that they provide a glimpse into the lives of people that oftentimes more traditional art objects do not.

DUNGY: Part of what draws us to ephemera is that it has quite literally touched us.

RUDNICK: There’s an intimate quality to a lot of these objects. So many of the objects that we have in the ephemera collection can fit in one’s hand, can be—and were—folded up and placed in someone’s pocket, were placed into albums. And so there is a relationship, I think, to one’s body because of these attributes that distinguishes ephemera from other typically more large-scale and less portable objects.

DUNGY: From era to era, paper reveals a lot about who we have been and how we have lived. One collection at The Met holds more than thirty thousand baseball cards, objects we’re very familiar with now but which have evolved considerably since their late-nineteenth-century beginnings.

RUDNICK: We have, for example, albums in Photographs from that period during the 1880s of players staged in a photography studio, about to catch a ball, and you can see the string from which the ball hangs. And I think I like that almost tentative aspect to these cards, because it’s the beginning of something that becomes very big. And I find them almost tender in a way.

DUNGY: Allison says that these printed paper objects were like an early form of social media.

RUDNICK: Before the age of the internet and television, even before radio, people communicated through paper. Because it was often inexpensive and accessible, it provided a means for people to forge relationships in all sorts of ways.

DUNGY: One of those relationships that people were forging was with the idea of celebrity. Those early portraits of athletes pretending to hit balls on strings would eventually morph into baseball cards that served as an incredibly successful marketing tool for tobacco and, later, gum and candy manufacturers. Initially, the stiff cards provided protection for the cigarettes inside a soft-sided pack, but people soon started buying the products so they could collect the images of the athletes and actresses. The cards were a way to connect with a broad audience. And one woman was unparalleled at using the medium. Her name was Omene.

RUDNICK: So Omene was a celebrity in her day. She was a belly dancer, and her entire biography was self-constructed. She claimed to have been from Istanbul. She said that her mother was a professional dancer. She claimed that she was forced to marry an Englishman when she was twelve years old, they had a child together and her husband left her and her daughter to fend for themselves.

DUNGY: Omene left England and came to the United States, where belly dancing had been introduced to the public via the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair.

RUDNICK: And so many people found it totally scandalous. But belly dancing did become, after that point, a mainstay of burlesque shows and carnivals. And Omene was really the best known practitioner of that dance form. What’s so fascinating about her story is in addition to constructing this autobiography, she was really expert at creating a[n] image that captivated the public. Her name was in the press all the time, not just for her dances, but her personal life was an object of fascination for people.

We need to look a little more closely [volume fades]

DUNGY: Here’s Allison describing one of Omene’s paper cigarette card images.

RUDNICK: She is completely shrouded in what looks like a cape that is covering her entire body, including her head. And the image is really small. So it’s a little difficult to make out all the details, but it does look like she’s wearing a veil over her face and she has some sort of headpiece on.

DUNGY: Omene intended to entice her audience.

RUDNICK: The costume is, I would say, kind of a generalized quote ‘exotic’ costume. Something that, in the minds of Americans in the late nineteenth century, probably just connoted this very kind of general sense of foreignness. And that’s something that people really responded to.

DUNGY: There are police reports that record Omene’s name as Nadine Osborne, or Madge Hargreaves. They have different records of her place of birth, and her lovers’ nationalities, all of which are more mundane than the image she projected. We may never know the truth of her story. But on those cards, Omene tapped into people’s interest in parts of the world they would likely never see. They could carry the adventures she offered in their own pockets.

RUDNICK: I think voyeurism is a big part of this story. I can think of some examples of postcards that we have that, you know, were inscribed on the back. We have valentines, greeting cards that are inscribed, as well. The valentines can be very intimate. There’s something that distinguishes ephemera from other objects that has to do with this glimpse into someone’s life on a very intimate, deep level.

DUNGY: That deep intimacy means that we can often see our own lives and experiences in the ephemera of others. Perhaps you had an elder who sent you greeting cards, too. If you ran across my shoebox and felt a connection to the cards inside, you wouldn’t need to know my uncle’s name, or even mine.

RUDNICK: Oftentimes—I would say the vast majority of the time—the owners of these objects, even the makers of these objects are anonymous. We know nothing about them. And so I think there is a tendency to fill in the blanks with one’s imagination about the lives of these people, too. So there’s a relationship that begs for, using your imagination and really putting yourself in the shoes of these people that we know very little about. But what we do know about them are the relationships they had. And to an extent the values they had, too.

DUNGY: We each have our own individual history with paper. But when you’ve devoted your life to conserving it, the plot thickens.

RACHEL MUSTALISH: When you’re working with paper to either repair or to preserve it, you do have a... talk about an intimate relationship. I mean, they almost become like your children.

DUNGY: More on that, after the break.

[Music. Sounds of paper tearing, then the sounds of pencils writing on paper]

—

DUNGY: When I think about paper, I think about revision. I’m a poet. So for me, paper is what I use to draft. I’m drafting and drafting and trying and trying to create something. I feel like I have to go through those drafts to get to what it is that I am really trying to say.

It’s the opposite of the age-old idea of putting something to paper: making something legally-binding, official, paper as a contract. For me, it can be fleeting. The beginning of the process. And like any new thing, it’s fragile.

MUSTALISH: Paper, like all natural materials, is moving toward decay. That is entropy in the universe. And so you’re trying to slow it down.

DUNGY: Rachel Mustalish is a paper conservator at The Met, who works on drawings and prints across the collection. She’s fighting the good fight against the agents of decay: stains, moisture, flaking, acids, glue. The paper conservation lab is well lit and modern, with long tables that hold all kinds of things: microscopes, woodworking and pottery tools, even dental implements (It turns out that the cotton picks used in root canals are great for adding tiny bits of adhesive).

Spread out on those tables are everything from medieval illuminated manuscripts to a 1937 celluloid image of Disney’s Snow White. Paper is so ever-present as to be forgettable. It’s in our hands, in our homes, clogging our mailboxes.

MUSTALISH: There’s always been this desire to be able to exchange information, to exchange technology, and to do it in a way that’s portable. And paper was the answer. It wasn’t going to be chiseled into a stone because you couldn’t bring that halfway across Asia to sort of share the... share the word, share the knowledge, share the images. If you think about what has done for the world, it’s impressive.

DUNGY: Paper is a technology that’s always kept pace with the desire to broadcast our thoughts.

MUSTALISH: In Rome, in the... I believe it was the eighteenth century, there were some political movements and they would print their ideas and slogans on these small pieces of paper, and then go sort of post them on a very public sculpture or monument or side of a church or side of a wall, and run off. It was like having a quick portable tweet, or that you would post a quick social media bit and run away, so you didn’t get arrested.

DUNGY: Paper was first documented in China, in the second century BC. Technically speaking, paper is a kind of felt. Plants are processed until they release their cellulose fibers, and these fibers are then processed into mats. Once the fibers in the mats have joined up, they are forever chemically changed.

MUSTALISH: And then as that technology evolved and then moved geographically—particularly as it went through India, the Middle East, and into Europe—the technology then became to find a source of cellulose that was more suited to the local available product, and so it became something that got made out of clothing.

DUNGY: Soon people figured out they could use plant-based textiles as the starting material for paper. Cotton fabrics, such as denim, were often made of very pure cellulose.

MUSTALISH: So for instance, in places with a lot of ship trade, there was a lot of hemp rope. And that, as it became no longer useful for ships, was still a source of cellulose that could be incorporated into paper.

DUNGY: This shortcut is logical, because papermaking was labor intensive.

MUSTALISH: And through all these early days, this was made by hand. Every single sheet was made by hand. And that’s sort of a mind-boggling thing to think about. It’s always, I think, a push-pull between available materials, technology changes, and economics that drive a lot of the industry of papermaking.

DUNGY: But paper isn’t all technology and economics. It’s also a powerful link between the person who worked on it and the person who’s holding it now.

MUSTALISH: When you do look at works of art that close, you can almost see the sort of hand that made them. When you look at drawings, you are looking at a direct line that goes, you know, from the artist’s brain into the work of art. I mean, that is an amazingly close connection. And to be able to hold that, own that, hold it in your hand, is incredibly moving.

DUNGY: But in order for you to experience that connection, a work has to be preserved well enough to get to you. That’s where Rachel comes in, doing everything from water baths of Dürer prints to the kind of microscopic repairs that make it look like she was never there at all.

MUSTALISH: As odd as this is going to sound, I really do like stain removal. I like the challenge of removing spots, disfiguring stains, things that have accidentally, over history, landed on a work of art that shouldn’t be there. Something we, um, call fly specks, which is basically poop and, um, you know, trying to remove these—

GYIMAH-BREMPONG: Wait, what? Fly poop?

MUSTALISH: Mm hmm. It’s called a fly speck.

GYIMAH-BREMPONG: [laughs]

DUNGY: That was producer Adwoa Gyimah-Brempong.

GYIMAH-BREMPONG: Carry on.

MUSTALISH: That’s the... that’s the euphemism. Yes. And it stains the paper. A little black dot.

DUNGY: There are bugs all over. There must be a lot of fly poop to worry about. How does The Met decide which drawings, photographs, or prints to save from fly specks and other indignities, before they deteriorate beyond hope of repair? How does something go from everyday ephemera to art worth the attention of someone like Rachel? Does something become important simply because it landed in an important place like a museum? Every person we asked had slightly different answers, but Rachel takes a long view. She says those aren’t decisions we can make with today’s eyes.

MUSTALISH: Once something comes into a public collection, I feel like it is the duty of the custodians to have it preserved, not just for who looks at it, thinks it’s important right now. But where it may, you know, fall into the future in terms of scarcity, rarity, also just knowledge. And you think about that a lot. There are things that were produced and there are meant to be a thousand of them, and there’s one left. Because things do get lost, burnt, stolen, degraded. And so it’s an interesting way of thinking about the long distance forever.

DUNGY: In and of itself, paper is not a particularly durable material. It’s not gold, or glass, or stone. But even if the material itself isn’t always made to last, paper’s hold on us definitely is.

MUSTALISH: Many important things happen on paper or have happened through paper, it can hold so much important information from love and death and marriage and money. And I think for those reasons, paper has an incredible amount of power.

DUNGY: That power shows no sign of slowing, even in our current digital age.

MUSTALISH: Despite its commonness sometimes—maybe even banality—it is one of the most amazing materials on planet Earth. From chemistry to its variety, to what you can use it for; what it looks like, what it smells like, what it feels like. I think that it is a magical substance that has changed the world.

[Music]

DUNGY: We can see the power of paper at play around the fourteenth of February, when valentines are handed out in school rooms all over the country. When I was a kid, there was a rule that if you gave a valentine to any child you had to give one to every child in the class. But nothing said I couldn’t make certain cards extra special to let a person know they were particularly important to me. An extra ‘XO’ here, a slightly bigger section of laced paper doily glued there. I still remember the smell and feel of all those cut-out paper hearts.

[Sound of cutting paper]

I always hoped the people I gave those special valentines to could tell the difference. But when it comes to deciphering the messages of love, Nancy Rosin is the expert.

NANCY ROSIN: The story of Valentine’s is really a story of people. Of how love was expressed over the ages, from the first little flower or a shell or a feather that might’ve been given. It was the person who was the Valentine, and over the years, it evolved to be the gift.

DUNGY: Nancy is a volunteer cataloger in The Met’s Department of Drawings and Prints, and her specialty is valentines. Back in the basement study room, she lays out an array of The Met’s extensive collection…

ROSIN: And they were really very beautiful … elaborately decorated with sequins… some had poetry...

DUNGY: ... Moving paper valentines called cobwebs, elaborately folded puzzle purses, and even a German map…

ROSIN: ... a map of matrimony, and this is very unusual…

DUNGY: … that illustrates the lands of lust, love, and divorce. These things are fun, and pretty. No wonder people love them.

ROSIN: Everyone could enjoy Valentine’s Day, whether it was just a little handwritten note. It was a time for love. It was a time to express your emotions: secret passion, desire, some, you know, some magic, some fantasy.

DUNGY: The desire to express desire seems to be a constant, though valentine styles varied widely across geography and cultural or economic station.

ROSIN: ... It’s all hand done...

DUNGY: And though lots of people made their own, there are those who made selling valentines into a profitable business.

ROSIN: This is a magical one because it’s so many layers...

DUNGY: Take, for instance, Esther Howland. Nancy calls her ‘the mother of the American Valentine.’

ROSIN: She graduated from Mount Holyoke Female Seminary in 1847, and they were not allowed to celebrate Valentine’s. Although Emily Dickinson was there at the same time, and she was writing Valentines. But they had a headmistress who told her graduates when they leave: ‘Go where no one else will go. Do what no one else will do.’ And I think Esther Howland felt that.

Her father was a stationer in Worcester, Massachusetts, and he received some valentines from England. And when she saw them, she thought, ‘I can do those. I can do better. I’m going to try it.’ So she got some supplies through her father and she made some samples, convinced her brother to take them on a sales trip, which he was not happy to do, but he did it anyway. She was hoping, I think for $200 worth of orders. We’re talking about 1847. And he came back with $5,000 worth of orders.

DUNGY: That would be the equivalent of about $170,000 today.

ROSIN: How was she to fill them? So she got her friends to create this assembly line.

DUNGY: It’s a wonderful story of American ingenuity and female entrepreneurship. It’s also a story of capitalism.

ROSIN: We can’t forget that, you know, the commercial people depended upon the passionate lovers to, you know, enrich their pocketbooks.

DUNGY: As is still true today, money considerations shaped almost every aspect of the cottage industry of love.

ROSIN: A woman might receive many valentines that were unsigned, and she would probably have to guess who sent it. And in fact, before there was a universal postal system, the recipient had to pay for the valentine by the number of miles it traveled, how many layers of paper. That’s why we didn’t use envelopes. They would be folded. But it’s written that some fathers refused, because their daughters received so many valentines. They wouldn’t accept them any longer because it cost too much money. They say that a very elaborate—and this one is one we attribute to Esther Howland because. none of her big ones are signed—an elaborate one might cost $50 back in the day. You could buy a horse and buggy for that much money.

DUNGY: It would be easy to become cynical about this, to see valentines as just a pretty paper way to commodify desire. Easy, but too simple. Nancy is The Met’s valentine lady, but she also built up quite a collection of her own. And that’s a story of love, too, because Nancy and her husband bonded over being collectors.

ROSIN: It was a wonderful marriage, almost fifty years. And we did it together. We empowered one another. And it was always a quest to find the earlier and find the history. Each one has a story.

DUNGY: Valentines can be a beautiful way to commemorate your love. But February fourteenth can be a rough day if the sentiments behind those cards never felt like they were meant to be for you.

AHMED: People love Valentine’s Day. I think for me it was a little bit opposite growing up. I felt like I was, like, the weird kid, so I never got, like, as many cool Valentine’s Day cards as everyone else did.

DUNGY: That’s Taz Ahmed again, whose Bangladeshi family shared a love of Archie comics across multiple generations and continents. Valentines, though… didn’t translate.

AHMED: I think one of my first memories was preschool, asking my mom for cards. She didn’t believe it, cause we’re immigrants, we’re brown. This whole idea of giving out like Valentine’s Day cards wasn’t a thing. So I think I remember getting, you know, like the blue cookie tins which had the little light paper in it, like the little tissue paper. I was like, ‘okay, this is the paper I’m going to use.’ I don’t even know if I was, like, allowed scissors, but I do remember using that, that was my paper. Like using found objects and like turning it into cards, because Mom wouldn’t let me buy anything.

DUNGY: Like Esther Howland, Taz found a way to make valentines even when she was told she shouldn’t. As she grew up, she ran into some troubling stereotypes about who those little paper hearts are for.

AHMED: The reason why I started the cards was cause I was in the book Love, InshAllah: The Secret Love Lives of American Muslim Women. And I was writing about love and you know, I love rom-coms, and people were asking me, ‘Oh, so do Muslim women fall in love?’ And I was like, ‘This is such a stupid question.’

DUNGY: So Taz started making Muslim valentines her friends could send to one another, with messages like ‘Heavy Vetting’ and ‘I’m Hal-ALL In.’

AHMED: Like, I had a card that said “I have a ji-hard-on for you.” And then I just, like, reflect it based on whatever’s happening in the moment. Like, it has to be political. Every card is political intentionally, because I want people to feel uncomfortable. I want people to feel uncomfortable and then I want them to laugh. I want them to laugh because they’re, like, uncomfortable. I think there’s a political power in that.

DUNGY: It’s not all political, though. The love in the valentines shines through.

AHMED: I went to a Muslim comedian’s show a couple months ago, and someone said that they got married because of my cards. They said, like, ‘I gave this card to this person, and she… you know, like, when I was courting this person, I gave her one of your cards, and then she liked me afterwards!’ And they just had a baby and I was just like, ‘oh, like, my cards are making babies!’ And I think that part is kind of cool.

DUNGY: One of the things that interests me about Taz’s story is the way her valentines write into silences. They create spaces for communication where such spaces had not existed before.

AHMED: When my mom went to Bangladesh when my grandmother was sick, you would just... like there was just silence on the phone. Like when you’re dealing with phone cards, and each call was worth like five dollars, you couldn’t afford silence.

And like, even with letters, right? The idea of having blank pages, that’s a waste of money, right? Like waste of space, right? Silence is space. The space to be silent is a luxury.

DUNGY: Even in its silence: paper speaks. Whether it’s a valentine’s card one person can hand to another, a provocative image accompanying a pack of smokes, or an old Archie comic book, paper carries with it the essence of who we are. It is an ephemeral vessel for art in its own right. And every day—whether hanging on a gallery wall or tucked into our pockets—it continues to change the world.

[Sounds of tearing paper]

—

DUNGY: I’m Camille Dungy, and this is Immaterial.

[Music]

Immaterial is produced by The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Magnificent Noise.

[Sounds of folding and ripping paper]

This episode was produced by Adwoa Gyimah-Brempong and Eleanor Kagan.

Our production staff also includes Jesse Baker, Eric Nuzum, and Elyse Blennerhassett.

And from The Metropolitan Museum—Sofie Andersen, Sarah Wambold, Benjamin Korman and Rachel Smith.

Sound design by Ariana Martinez. Mixing by Ariana Martinez and Kristen Mueller. This episode includes original music composed by Austin Fisher.

Fact-checking by Christine Baird.

The podcast is made possible by Dasha Zhukova Niarchos.

Additional support is provided by Bloomberg Philanthropies.

This episode would not have been possible without Mindell Dubansky, Head of the Sherman Fairchild Center for Book Conservation at The Met’s Watson Library; Nadine Orenstein, Drue Heinz Curator in Charge of the Department of Drawings and Prints; Conservator Rachel Mustalish; and Associate Curator Allison Rudnick.

To see the artworks featured in the episode and to learn more about this series, visit The Met’s website at metmuseum.org.

I’m Camille Dungy.

[Music. Sound of folding paper]

###