The sculptor Nairy Baghramian sees the formidable niches in The Met’s facade as a kind of membrane, neither inside nor outside, but mediating between the carefully curated institution and the unpredictable space of the street. If the collections inside the Museum’s walls carry the weight of official history—arranged chronologically, sealed under glass, and guarded for safekeeping—then the niches, left unfinished without their intended figures, remind us of history’s open-endedness, of the many plans that never came to fruition, and the other possible futures that might have been. As a public space of chance encounter, the niches become part of the dynamic charge of city life.

I encountered Baghramian’s facade commission, Scratching the Back (2023), a few weeks before the one-year anniversary of the Women, Life, Freedom movement in Iran, where Baghramian was born and lived until she became a refugee in Germany at age thirteen. I was immersed in preparations for several events commemorating and analyzing Iran’s unprecedented revolutionary feminist uprising, which still felt like a shock from which we—in Iran and in the diaspora—had not recovered. In fact, many of us did not want to recover: we wanted to pause and reflect on the magnitude of what had happened, the unthinkable that had yet to be fully theorized, a crack in history that had opened onto the unknown.

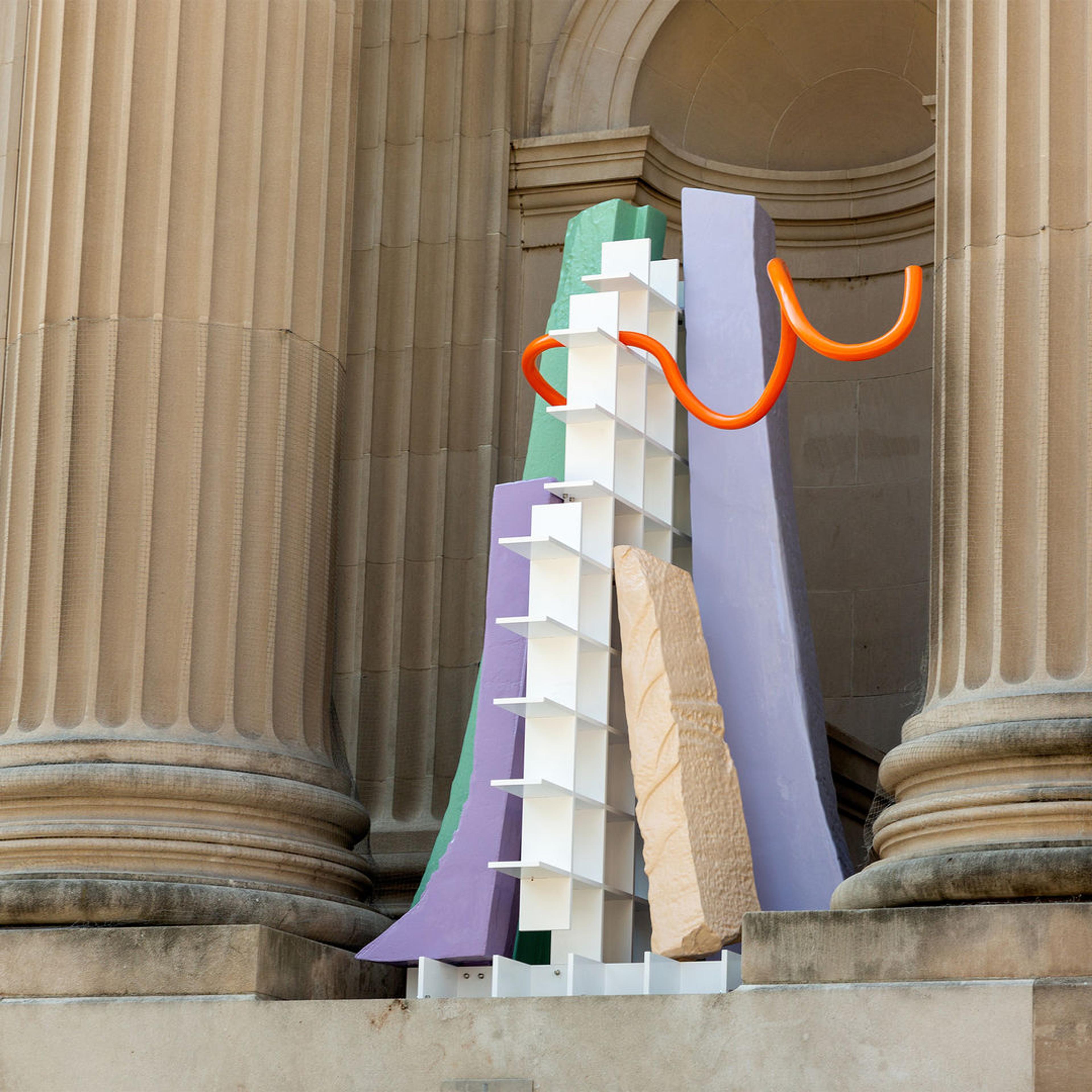

All four sculptures comprising Nairy Baghramian’s facade commission, Scratching the Back (2023), seen from Fifth Avenue

Although the four sculptural works that make up this commission were not conceived in response to the women-led uprising, they were imagined and crafted during the same year of its unfolding. It had been a year of defiance when many categories congealed by official histories were thrown into the air and a mass movement insisted on redefining the meaning of freedom beyond state sovereignty. The tragic death of a young Kurdish woman, Jina (Mahsa) Amini, at the hands of the notorious “morality police,” who had arrested her for improperly wearing her mandatory headscarf, unleashed a revolt led by women and girls, led from the marginalized and oppressed classes of Iranian society— from the Kurdish and Baloch provinces, from the queer and trans communities, from the youth who more than any other demographic recognized that to accept the status quo was to embrace despair. There has been an overwhelming proliferation of Iranian artistic production inspired by the Women, Life, Freedom movement. Within the first year, exhibitions were organized outside Iran, sometimes igniting protest from Iranian diasporic artists who objected to the repetition of familiar tropes of Muslim women’s oppression and abjection. Art historians and critics have attempted to contextualize Iranian protest art within a representational landscape that is shaped by the forces of contemporary geopolitics and older colonial legacies. Familiar dichotomies of veiled and unveiled women, for example, reify notions of civilizational clash: West vs. East, secular vs. Muslim, liberated Western women vs. oppressed Muslim women. These binaries have constrained our political and aesthetic horizons for too long, to the detriment of both the political and the cultural spheres of imagination.

Women burn hijab at a protest in Bandar Abbas over the death of Jina (Mahsa) Amini, October 2022

When Iranian women took off their government-mandated veils, spun them in the air, and set them on fire, dancing in the streets, they interjected new political subjectivities and demands into the realm of the possible, embodying a vision of freedom and sovereignty that is neither westernized nor policed by state-centered definitions of cultural authenticity. This energy, this joy, this assertion of life against death, this collective reorientation toward the feminized and marginalized as agents of revolutionary transformation, is difficult to sustain on the streets and to represent through visual cultural production. Artistic engagements with death, torture, grief, and martyrdom, which call attention to the tremendous violence meted out by the Iranian state against protesters and also build on religious and aesthetic tropes woven through hundreds of years of Iranian visual culture, have featured prominently in exhibitions such as Anonymously, Iran (2023), while comparatively little artistic energy has gone toward interpreting the revolutionary imagination that has inspired and buoyed the movement.

In this context, Baghramian’s Scratching the Back struck me as a refreshing exploration of unruliness—a rebellion of form, shape, and color against pre-existing spatial and aesthetic parameters. Rather than take their places obediently within the allotted confines of the niche, each sculpture appears to burst forth, to provoke and transgress. This brazen combination of organic shapes, rocky surfaces, grid-like constructions, and rippling lines appears to defy the rules of gravity. At first, it is disorienting. What is one looking at? How does one look when there is no single focal point? But then the possibilities bubble up, overflowing from the space, the form, and the moment, to suggest a multitude of meanings.

Rather than take their places obediently within the allotted confines of the niche, each sculpture appears to burst forth, to provoke and transgress.

Baghramian has long been obsessed with the backs of things, curious about what is obscured or overlooked by the privileged forward-facing presentations of three-dimensional objects. As a child, she would stare into shop windows and then go home and draw what she imagined the objects in the window looked like from the back. This exercise, and the artistic practice that emerged later, render the back as a site for imagining the unknown. What happens when we pay attention to that which is normally hidden from view? By refusing to privilege the front of an object as the vantage point of comprehension, Scratching the Back manifests a refusal of dominant ways of seeing and knowing.

This non-normative approach to visual culture exemplifies what Gayatri Gopinath has called the “aesthetic practices of queer diaspora,” ways of seeing that “suggest alternative understandings of time, space and relationality that are obscured within dominant history.”[1] As Baghramian put it quite succinctly in a 2022 interview, “Modernity is heterosexual.” Sustaining it requires the rationalization of time, space, and human behavior, subordinating all to the forward march of progress. Within and against this overarching structural logic, Baghramian has long played with queer modes of disrupting straight lines, smooth surfaces, spatial expectations, and linear temporality. For example, in her Misfits series (2021), the playful scattering of objects appears as an homage to what modernity has discarded as unproductive, that which cannot assist the relentless drive toward ever-greater accumulation.

Two men kiss at the foot of Azadi Tower in Tehran, November 2022

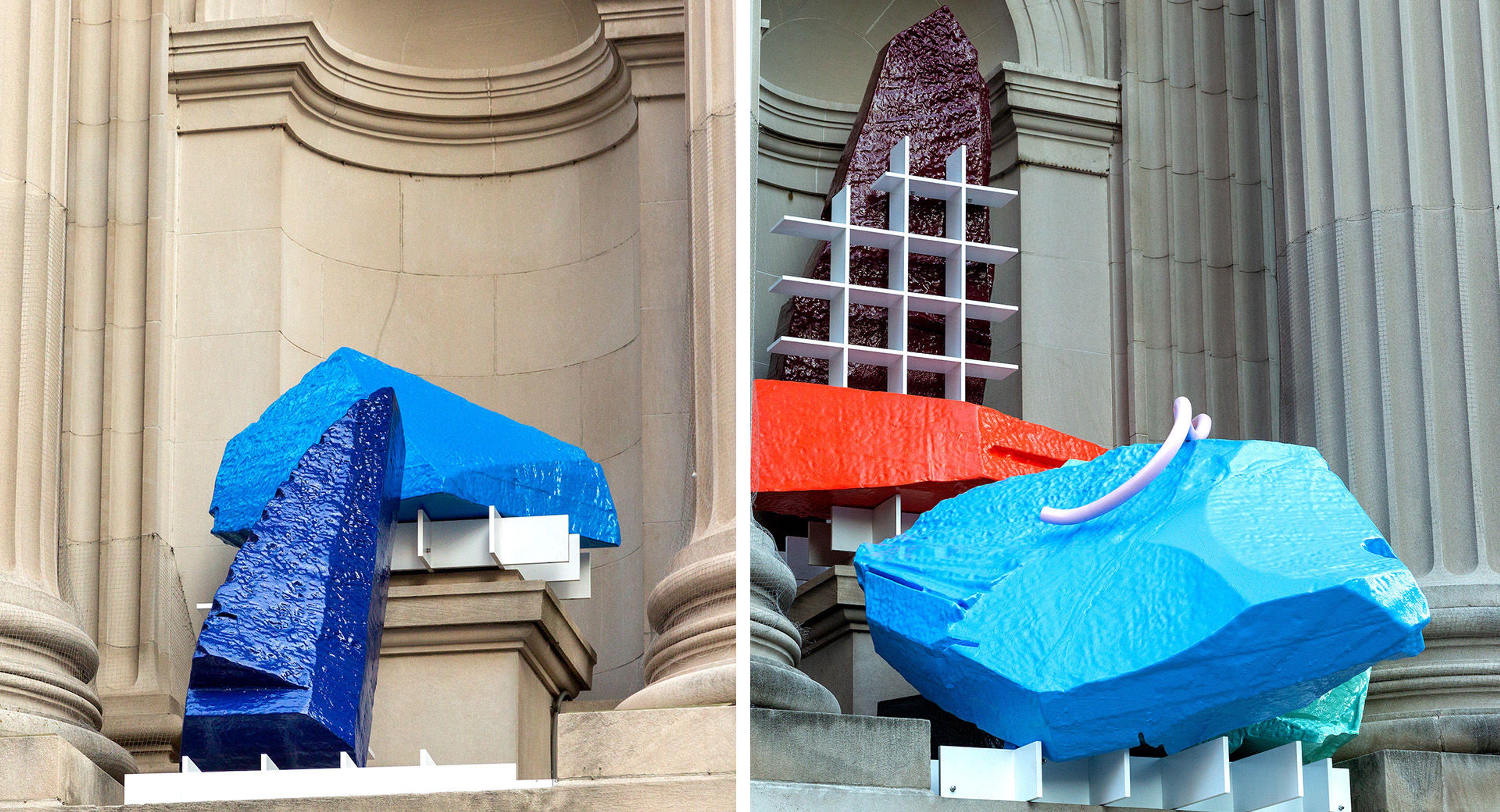

The four sculptures that make up Scratching the Back are similarly playful and irreverent, sharing affective resonances with iconic scenes from the Women, Life, Freedom movement: women dancing in public when it is forbidden, college students defying gender segregation to eat lunch together on campus, a same-sex couple kissing in the street. Baghramian’s sculptures invite us to consider what we might glean from objects that enact a queering of spatial orientation by refusing the front-back binary. In Scratching the Back: Drift (Pink Ribbon), to the immediate right of The Met’s main entrance, we see three boulder-like constructions assembled as if they have fallen off the grid that towers over them. If this is the detritus that crumbles from the edifice of modernity, then it resists a tragic reading. The brightness of the red, the blue, and the green coloration is irresistibly joyful, a cacophonous palette that jars the senses into a heightened state of liveliness. The pink ribbon seems to emerge from the rubble, curling and unfurling with an indomitable creative will that might be whimsical if not for the alarming wall of red looming behind the grid. This composition suggests that the structural violence of modernity and the desire to flourish and thrive coexist, the latter rising up in often unexpected ways.

Nairy Baghramian’s Scratching the Back: Drift (Without Ribbon) at left, and Scratching the Back: Drift (Pink Ribbon) at right

This transgressive approach to color, form, and space is carried through each of the four installations, three with ribbon and one without. Scratching the Back: Drift (Without Ribbon) is the quietest of the sculptures, though the stunning boldness of deep blue juxtaposed against turquoise sustains the mood of the commission as a whole. Here the stark rock-like forms rest against one another as if offering solace for modernity’s irreparable losses, and the shades of blue invoke an ocean of grief that threatens to overtake us all. Baghramian is interested in the “flotsam and jetsam” of modern life, in the waves of migration that generate unpredictable encounters between objects, ideas, and aesthetic forms. Her work makes space for history’s misfits to play among the ruins, to gesture toward other ways of seeing and moving in our precarious times. And perhaps this is the most we can ask of our artists, that their work opens, in Baghramian’s words, “a little door to the future.”

Notes

[1] Gayatri Gopinath, Unruly Visions: Aesthetic Practices of Queer Diasporas (Durham: Duke University Press, 2018), 5. Return