Begin the tour

Join guest host Katy Hessel—an art historian, curator, and author known for the international bestseller The Story of Art Without Men and The Great Women Artists podcast—as she highlights women artists who have been excluded from art-historical narratives and provides contemporary perspectives on issues of inclusion in the Museum and art world at large.

In conversation with Met experts, Hessel examines stories of people who went against the grain despite the odds being against them. The tour aims to encourage as many people as possible, at all levels of art-historical knowledge, to seek out work by these artists in museums.

- 10 audio stops

- Audio runtime: 30 minutes total

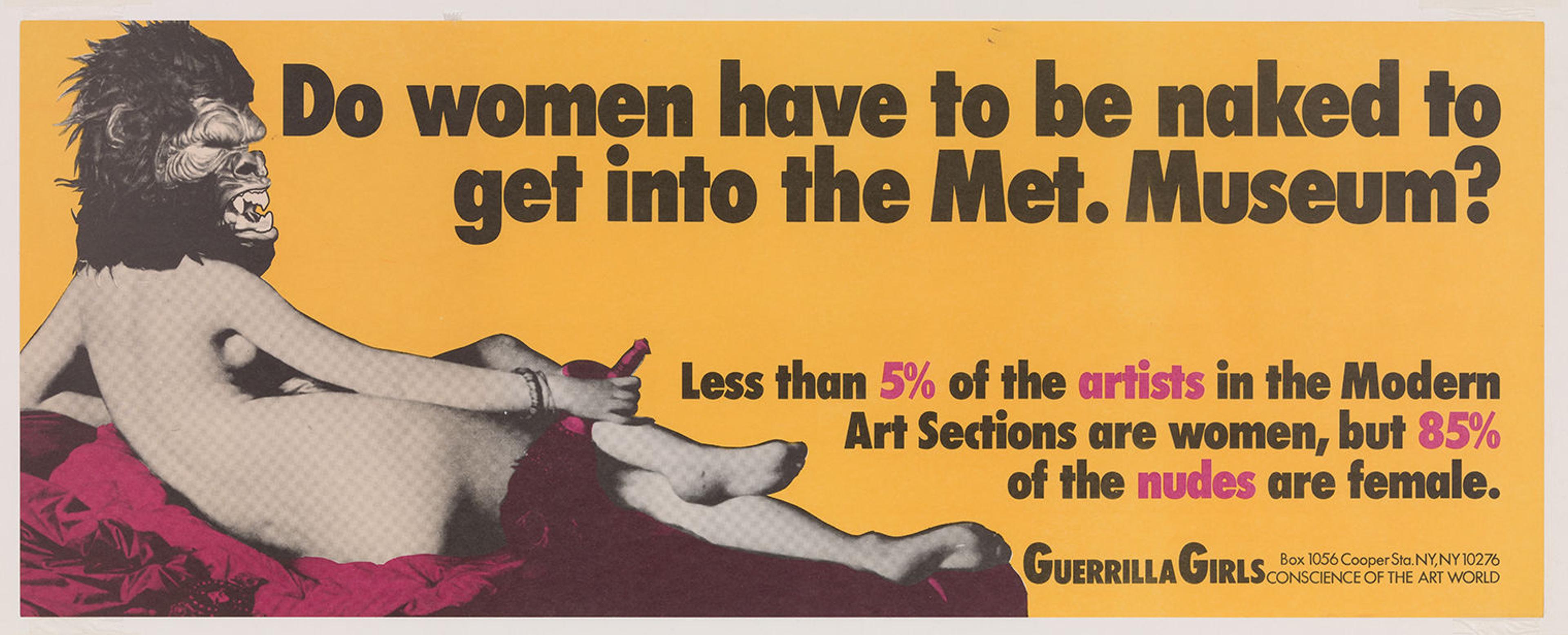

Guerrilla Girls’s Do Women Have To Be Naked To Get Into the Met. Museum?

Tour Introduction

Museums Without Men: Guerrilla Girls

Have you ever wandered the galleries at The Met and thought about the gender representation on display? In 1989, the Guerrilla Girls questioned this and famously found out that “Less than 5% of the artists in the Modern Art sections are women, but 85% of the nudes are female.” Katy Hessel and Met curator Allison Rudnick revisit this 20th-century art collective’s public bus campaign that challenges patriarchal assumptions about the legitimacy of artists.

Guerrilla Girls (American, established 1985). Do Women Have To Be Naked To Get Into the Met. Museum?, 1989. Lithograph, 11 x 28 in. (27.9 x 71.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Scott, Lauren, and Lily Nussbaum, 2021 (2021.70). © Guerrilla Girls, courtesy guerrillagirls.com

Rosa Bonheur’s The Horse Fair

On view, Gallery 812

Museums Without Men: Rosa Bonheur

Katy Hessel visits one of her favorite works in The Met, painted in 19th-century Paris, when the Academy’s rigid hierarchies reigned supreme. At the time, paintings of the human figure were considered the most prestigious genre of artmaking—but women were barred from the life room, where they could paint from observation of live models. Rosa Bonheur was not deterred. Turning to images readily available to her, she painted The Horse Fair (1852–55), a monumental depiction of a horse market.

Rosa Bonheur (French, 1822–1899). The Horse Fair, 1852–55. Oil on canvas, 8 ft. 1/4 in x 192 ft. 7 1/2 in. (244.5 x 506.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Cornelius Vanderbilt, 1887 (87.25)

Marie Denise Villers’s Marie Joséphine Charlotte du Val d’Ognes

On view, Gallery 634

Museums Without Men: Marie Denise Villers

In 1917, The Met purchased this portrait of a young woman artist for $200,000. At the time, it was thought to be painted by the male Neoclassical artist, Jacques-Louis David. Art historian Kathryn Calley Galitz shares how the scholar Margaret Oppenheimer made a surprising discovery when she reevaluated that attribution more than half a century later.

Marie Denise Villers (French, 1774–1821). Marie Joséphine Charlotte du Val d’Ognes (1786–1868), 1801. Oil on canvas, 63 1/2 x 50 5/8 in. (161.3 x 128.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Mr. and Mrs. Isaac D. Fletcher Collection, Bequest of Isaac D. Fletcher, 1917 (17.120.204)

Edmonia Lewis’s Hiawatha & Minnehaha

On view, Gallery 759

Museums Without Men: Edmonia Lewis

These two sculptures of Native American figures, Minnehaha and Hiawatha, are chiseled with incredible skill and restraint by the Black and Native American sculptor, Edmonia Lewis. Art historian Lisa E. Farrington recounts how this talented artist and savvy businesswoman rose to prominence after the Civil War. Despite consistent backlash from the wealthy white elites of the art world, Lewis achieved great success.

Left: Edmonia Lewis (American, 1844–1907). Hiawatha, 1868. Marble, 13 3/4 x 7 3/4 x 5 1/2 in. (34.9 x 19.7 x 14 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Morris K. Jesup and Friends of the American Wing Funds, 2015 (2015.287.1). Right: Edmonia Lewis (American, 1844–1907). Minnehaha, 1868. Marble, 11 5/8 x 7 1/4 x 4 7/8 in. (29.5 x 18.4 x 12.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Morris K. Jesup and Friends of the American Wing Funds, 2015 (2015.287.2)

Mary Cassatt’s Young Mother Sewing

On view, Gallery 768

Museums Without Men at The Met: Mary Cassatt

Met curator Laura Corey considers the legacy of Mary Cassatt, an American Impressionist painter known for her sensitive portraits of motherhood who also played a critical role in influencing American collectors to purchase Impressionist paintings. Corey notes that some of the most significant works of Impressionist art at the Museum came from the donation of Louisine Havemeyer’s collection, which was assembled with Cassatt’s guidance.

Mary Cassatt (American, 1844–1926). Young Mother Sewing, 1900. Oil on canvas, 36 3/8 x 29 in. (92.4 x 73.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, H.O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs. H.O. Havemeyer, 1929 (29.100.48)

Leonora Carrington’s Self-Portrait

On view, Gallery 901

Museums Without Men: Leonora Carrington

“I didn’t have time to be anyone’s muse,” the artist and writer Leonora Carrington once said. “I was too busy rebelling against my family and learning to be an artist.” While viewing Carrington’s famous self-portrait, Katy Hessel rethinks the role of muses and reflects on the gap between how artists represent themselves and the narratives that eclipse their identities.

Leonora Carrington (Mexican [born England], 1917–2011). Self-Portrait, ca. 1937–38. Oil on canvas, 25 5/8 x 32 in. (65 x 81.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Pierre and Maria-Gaetana Matisse Collection, 2002 (2002.456.1). Image © 2021 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Firelei Báez’s Olamina

On view, Gallery 915

Museums Without Men: Firelei Báez

Firelei Báez explains how her painting is an ode to Lauren Olamina, the protagonist of Octavia Butler’s Earthseed series. Set in a dystopian near-future United States, the novels imagine a world on the brink of political and environmental collapse. Against this backdrop, Olamina establishes a new religion to envision a future liberated from the unrelenting demands of industrialization—one that centers moments of rest and reflection.

Firelei Báez (Dominican, b. 1981). Olamina (How do we learn to love each other while we are embattled), 2022. Oil and acrylic on inkjet on canvas, 86 1/2 in. x 9 ft. 6 1/2 in. x 1 1/2 in. (219.7 x 290.8 x 3.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Purchase, Civic Practice Partnership Artist Residency, Anonymous, and Lila Acheson Wallace Gifts, 2023 (2023.355). © Firelei Báez

Discover more works by great women artists in The Met collection online

There are countless works by women artists in the collection that reside out of sight in storage facilities. In many cases, this invisibility is a symptom of the materials used to create artworks. Works on paper and textiles are extremely sensitive to light, temperature, and humidity. To ensure that these works are preserved, they can only be on view for short periods of time.

In this next section of the tour, we highlight some of these incredible works not currently on view. Though they may be out of sight, curators and artists attest to their wide-reaching influence and advocate for sharing the stories of these works beyond the walls of the Museum.

Wangechi Mutu’s The Seated I

Online only

Museums Without Men: Wangechi Mutu

In 2019, the Kenyan American artist Wangechi Mutu was invited to make sculptures for The Met’s inaugural facade commission. In this episode, she describes how she began her process by examining the Museum’s Beaux-Arts architecture, focusing on a very curious type of architectural feature called caryatids. Met curator Brinda Kumar discusses the ways Mutu’s work both represents and subverts traditional structures and the narratives they upheld.

Wangechi Mutu (Kenyan, b. 1972). The Seated I, 2019. Bronze, 79 1/8 x 33 1/2 x 44 1/2 in., 842 lb. (201 x 85.1 x 113 cm). Purchase, Hazen Polsky Foundation Fund and Cynthia Hazen Polsky Gift, in celebration of the Museum's 150th Anniversary, 2020 (2020.119). © Wangechi Mutu. Courtesy of the Artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels

Emma Civey Stahl’s Woman’s Rights Quilt

Online only

Museums Without Men: Emma Civey Stahl

When you imagine a truly “great” work of art, what comes to mind? Perhaps a massive oil painting in a gilded frame, or a carefully chiseled marble bust. Met curator Amelia Peck shares that before most women had the resources to pursue sculpting or painting, they channeled their creative energies into an art form they could pursue in their own homes: quiltmaking.

Emma Civey Stahl (American). Woman’s Rights Quilt, ca. 1875. Cotton, 70 x 69 1/2 in. (177.8 x 176.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Funds from various donors, 2011 (2011.538)

Mrinalini Mukherjee’s Aranyani

Online only

Museums Without Men: Mrinalini Mukherjee

In 2019, The Met held the first U.S. retrospective of Indian artist Mrinalini Mukherjee. The exhibition included Aranyani (1996), a towering sculpture made of knotted colorful rope that was placed directly on the gallery floor. Through exploring Mukherjee’s work and career trajectory, Met curator Brinda Kumar reflects on how museums may work to more proactively shine a light on women artists.

Mrinalini Mukherjee (Indian, 1949–2015). Aranyani, 1996. 55 7/8 x 50 x 41 in. (142 x 127 x 104 cm). Gift of the Estate of Mrinalini Mukherjee, in celebration of the Museum's 150th Anniversary, 2020 (2020.211.2) © Mrinalini Mukherjee Foundation

This audio tour is one in a series of tours called Museums Without Men produced by Katy Hessel in collaboration with institutions across the globe, such as the Fine Arts Museum San Francisco, the Hepworth Wakefield, the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, and Tate Britain. The series encourages museum visitors to seek out work by great women and gender non-conforming artists in these institutions who, simply by virtue of their gender, were often overlooked and underrepresented.