A landmark of neoclassical portraiture and a cornerstone of The Met collection, Jacques Louis David’s Antoine Laurent Lavoisier (1743–1794) and Marie Anne Lavoisier (Marie Anne Pierrette Paulze, 1758–1836)presents a modern, scientifically minded couple in fashionable but simple dress, their bodies casually intertwined. Antoine Laurent Lavoisier is often referred to as the “father of modern chemistry” and Marie Anne Lavoisier is known as a key collaborator in his experiments—aspects of the couple’s personality that have been well served by this famous image.

Left: Jacques-Louis David (French, Paris 1748–1825 Brussels). Antoine-Laurent and Marie-Anne Pierrette Paulze Lavoisier, 1788. Oil on canvas. 102 1/4 x 76 5/8 in. (259.7 x 194.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Mr. and Mrs. Charles Wrightsman Gift, in honor of Everett Fahy, 1977 (1977.10). Center: Infrared reflectogram (IRR) of David’s portrait of the Lavoisiers. Vague indications of changes to painted passages are visible as slightly dark shapes, such as the mysterious form across Marie Anne Lavoisier’s hair. Photo credit: Department of Paintings Conservation, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Originally published by S.A. Centeno, D. Mahon, F. Carò and D. Pullins, Heritage Science (Springer Open), 2021. Right: Combined elemental distribution map of lead (shown in white) and mercury (red) obtained by macro X-ray fluorescence (MA-XRF). This MA-XRF provides a detailed map of the hidden paints, with red areas corresponding to the red pigment vermilion and white to lead white. Photo credit: Department of Scientific Research and Department of Paintings Conservation, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Originally published by S.A. Centeno, D. Mahon, F. Carò and D. Pullins, Heritage Science (Springer Open), 2021.

Since entering the collection in 1977, when Charles and Jayne Wrightsman purchased this painting for the Museum, it has remained on constant display in the galleries. Its pristine condition kept it out of the Museum’s Department of Paintings Conservation until 2019, when curator emerita Katharine Baetjer suggested the removal of a degraded synthetic varnish on the painting’s surface. Initial observations by conservator Dorothy Mahon prompted an extended campaign of technical and art-historical analysis in dialogue with research scientist Silvia A. Centeno and associate curator David Pullins.

At nearly nine feet high by six feet wide, any treatment of this portrait represents a significant commitment. After arriving in Conservation in March 2019, Dorothy spent nearly ten months carefully removing the varnish. One challenge was determining a solvent mixture that was not only safe for the painting but also nontoxic for the conservator. It was in the course of this intimate, daily relationship of poring over the surface that certain irregularities became apparent: points of red paint protruding from beneath the surface above Madame Lavoisier’s head; red paint showing through the cracks of the blue ribbons and bows of her dress; and, finally, a series of minute drying cracks suggesting that something was concealed beneath the red tablecloth in the foreground.

Conservator Dorothy Mahon performs conservation treatment on David’s portrait of the Lavoisiers in The Met’s Paintings Conservation studio. Photo credit: Eddie Knox © Oxford Films, 2020

Much of the technology at the heart of this project did not exist when this painting first arrived at the Museum; until recently, many key findings would have been impossible. A combination of non-invasive infrared reflectography (IRR) and macro X-ray fluorescence mapping (MA-XRF) were employed to image and analyze the work. IRR imaging uses infrared light to penetrate the upper layers of paint to reveal changes to the composition. MA-XRF reveals the distribution of elements composing the pigments in the paints, including those below the surface, thereby providing detailed maps allowing for indications of underlying paints. Because the canvas is so large, sections were chosen and studied before comprehending the whole. In acquiring the IRR images, we sought the assistance of Evan Read, Manager of Technical Documentation, who used a specialized camera to record the entire painting. MA-XRF mapping produces a set of data that can only be visualized when processed and interpreted by specially trained conservation scientists.

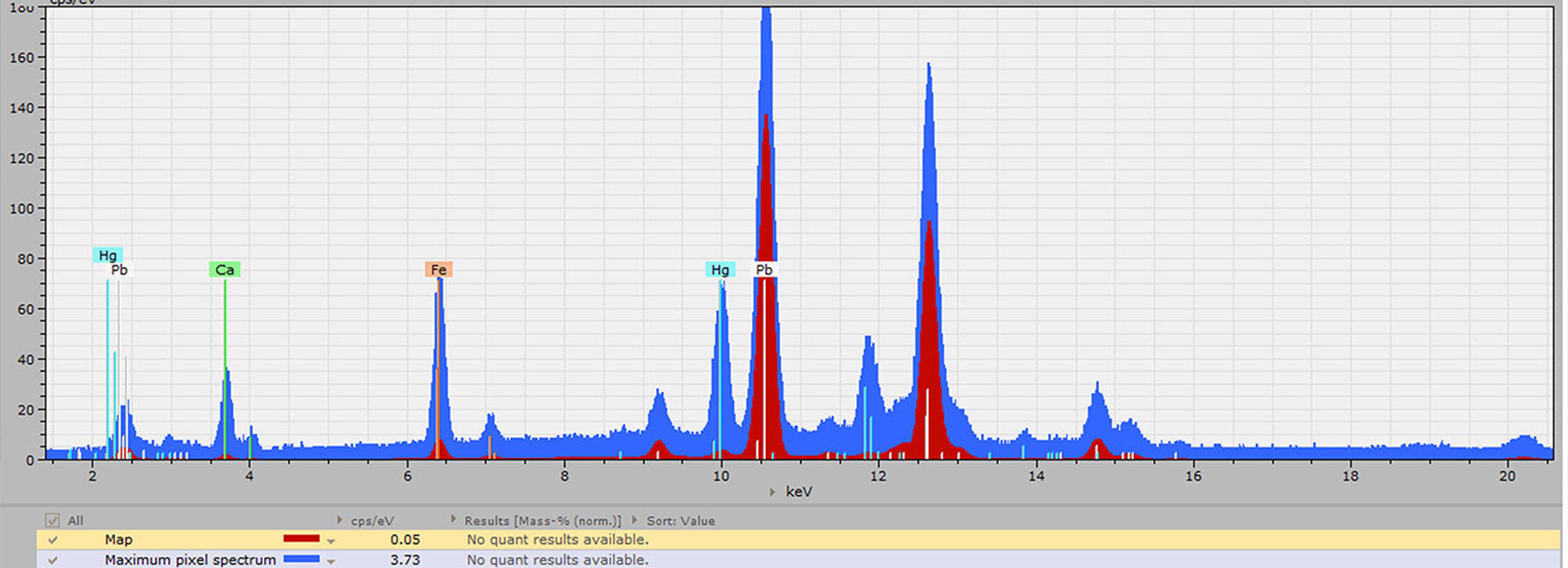

X-ray fluorescence spectra acquired in an area above Madame Lavoisier’s head, showing peaks characteristic of elements composing the pigments in the visible paints and in the early composition hidden below the surface. Calculating and plotting the information contained in these spectra results in elemental distribution maps. Originally published by S.A. Centeno, D. Mahon, F. Carò and D. Pullins, Heritage Science (Springer Open), 2021.

Following some 270 hours during which the surface was scanned, Silvia’s expertise made it possible to transform raw data into meaningful images and identify various elements in the paint layers. The colors assigned to the MA-XRF maps are arbitrary but chosen to represent the various elements found in given pigments, thereby revealing a sense of the colors of the underlying paints. Dorothy and Silvia used these images, together with the observation and chemical analysis of a very small number of microscopic paint samples, to further interpret the elemental maps and assess the characteristics and color of the paint hiding below the surface. In this task, the expertise of research scientist Federico Carò in chemical analyses using a scanning electron microscope (SEM) was crucial.

Research scientist Silvia A. Centeno acquiring X-ray fluorescence maps of David’s portrait of the Lavoisiers. Photo credit: Dorothy Mahon, 2019

Once a clearer picture of the underlying composition emerged, David began to contextualize and study the newly discovered first version as if it were a whole new painting, a lost work come to light. What would it have meant if this were that image that had come down to us rather than the portrait known today? How did the two relate? What decisions had been made, and when? Just as a good doctor will comprehend an X-radiograph and notice things a less experienced eye might miss, so, too, was a significant degree of knowledge required for a proper interpretation by The Met’s team. Working in tandem, Conservation, Scientific Research, and several curatorial departments united expertise in the material aspects of eighteenth-century painting, the limits of data produced by available technology, and the socio-artistic context of late 1780s France.

Reinstallation of David’s portrait in The Met’s European Paintings galleries in 2020, following conservation treatment and technical analysis. Photo credit: Eddie Knox © Oxford Films, 2020

Among the most spectacular findings was that, beneath the austere background, Madame Lavoisier had first been depicted wearing an enormous hat decorated with ribbons and artificial flowers. The red tablecloth was once draped over a desk decorated in gilt bronze and, perhaps most surprisingly, the scientific instruments that announce the couple’s place at the birth of modern chemistry—and so define the portrait today—were all the result of a later campaign that reworked how the Lavoisiers were presented.

The Parisian fashion press was so active, and trends so rapid, that the invention of a particular hat or dress can often be dated to within a few months. In conversation with The Costume Institute’s Jessica Regan, David reviewed a range of periodicals from the period and found that the distinctive red-and-black hat would have been known as a chapeau à la Tarare, named after operas by Pierre Beaumarchais, that emerged in the late summer and fall of 1787.

Left: Detail of plate 2, by A.-B. Duhamel Jean-Florent Defraine. From La Magasin des Modes Nouvelles, no. 36 (10 November 1787). Hand-colored engraving, 7 x 7 4/5 in. (17.9 x 19.9 cm). Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. Right: Detail of hat revealed through the combined elemental distribution map of lead (shown in white) and mercury (shown in red) obtained by macro x-ray fluorescence (MA-XRF) in Jacques-Louis David’s Antoine Laurent Lavoisier (1743–1794) and Marie Anne Lavoisier (Marie Anne Pierrette Paulze, 1758–1836) (1788). Photo credit: Department of Scientific Research, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Originally published by S.A. Centeno, D. Mahon, F. Carò and D. Pullins, Heritage Science (Springer Open), 2021

While we have little documentation about the commission, this starting date made perfect sense since the Lavoisiers paid the artist for completed work in December 1788. The red paint observed through the craquelure of the blue ribbons—and corroborated by the MA-XRF and the analysis of paint samples revealing vermilion—was a logical complement to the hat. Other fashion plates indicate that belts and ribbons typically coordinated with the hat set against the simple linen of the dress, known as a chemise à la reine.

Examination of the Lavoisiers’ inventories allowed David to posit objects that may have been represented in the painting. For example, the desk was of such a specific neoclassical form that it seemed likely to be the sitters’ own. Discussion with Daniëlle Kisluk-Grosheide, Henry R. Kravis Curator in the Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts, as well as furniture specialists outside the Museum, narrowed the range of potential furniture makers and dates.

Contextualizing the painting within fashionable portraiture of the 1780s, it was possible to identify a range of close comparisons that were surely familiar to the artist and likely inspired or informed how he worked. Even the most revolutionary painters do not exist in a vacuum, and this highly successful artist was certainly attuned to what spelt success at the Paris Salon. Most strikingly, the first version clearly evinced knowledge of new forms of portraiture pioneered by women painters in the period. Two artists well represented at The Met, Adelaïde Labille-Guiard and Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, painted multiple works that were likely on the minds of both the artist and his sitters.

Left: Adélaïde Labille-Guiard (French, 1749–1803). Self-Portrait with Two Pupils, Marie Gabrielle Capet (1761–1818) and Marie Marguerite Carreaux de Rosemond (died 1788), 1785. Oil on canvas, 83 × 59 ½ in. (210.8 × 151.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Julia A. Berwind, 1953 (53.225.5) Right: Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun (French, 1749–1803). Comtesse de la Châtre (Marie Charlotte Louise Perrette Aglaé Bontemps, 1762–1848), 1789. Oil on canvas, 45 x 34 1/2 in. (114.3 x 87.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Jessie Woolworth Donahue, 1954 (54.182)

In addition to modifications of existing formats and poses popular in 1780s portraiture, the overall development of the Lavoisiers’ portrait moved away from foregrounding their identity as tax collectors (the source of their fortune that allowed for such a luxurious commission) and toward underscoring their scientific work. It is, of course, the latter identity that is so clearly defined today and has helped perpetuate their fame both in art history and the history of science. But another identity has been quite literally concealed in the present portrait, and its revelation offers an alternate lens for apprehending Lavoisier not for his contributions to science but simply a wealthy tax collector who could afford the whims of fashionable dress and portraiture that sent him to the guillotine in 1794.

Encompassing nearly three years of ongoing cross-departmental collaboration that brought together distinct fields of expertise and training, the results of our analysis and research attest to the very active lives led by objects long after they enter the Museum’s collection. In late 2020, with technical work on the painting complete for now, the restoration of the painting was finished. Dorothy retouched small losses and the surface was revarnished. With the help of our expert team of art handlers, the painting returned to its frame and found its place on the wall, an anchor of The Met’s exceptionally rich neoclassical paintings galleries.

Learn more about the team’s findings in Heritage Science and The Burlington Magazine.