The United States has historically been affected by high water levels and floods. Due to the man-made global warming crisis, however, such natural disasters now occur more frequently.[1] A selection of artworks from the Drawings and Prints collection made between 1868 and 2021 illustrates flooding, showing homes submerged in water and those who suffered inundation.Other prints use metaphor to emphasize the destruction caused by natural disasters, displaying the collective and individual dimensions of tragic events. Some particularly poignant representations underscore the disproportionate impact of flooding—the most prevalent and costly type of natural disaster in the country—on Black communities in different regions.[2] Through the lens of art, we see the experiences of past disasters from some distance and reflect on possible ways of building a more sustainable and equitable present.

Two nineteenth-century, hand-colored lithographs by Frances Flora Bond Palmer (1812–1876) for Currier & Ives contrast different moments of the same landscape before and after flooding, illustrating how inundation affects differently and disproportionately specific sectors of the population. Currier & Ives, a prominent printmaking firm, published over thirty representations of the Mississippi River during the period.[3] These illustrations depicted the river as a grand navigation route for large steamboats, hinting at the rapid industrialization in the region. While living in New York in 1868, Palmer made two different representations of the river from the same perspective, featuring a startling difference related to the level of the water currents. In Low Water in the Mississippi (1868), two steamboats and a smaller boat cruise through surprisingly low river waters, allowing viewers to see parts of the streambed. The background depicts plantation lands, and the foreground features a group of Black women and men enthusiastically dancing to a banjo player. Overall, the idealized composition presents a peaceful afternoon in a southern landscape.

Frances Flora Bond Palmer (American (born England), Leicester 1812–1876 New York). "High Water" in the Mississippi, 1868. Hand-colored lithograph, 17 1/2 × 27 5/8 in. (44.5 × 70.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Adele S. Colgate, 1962 (63.550.43)

By contrast, Palmer’s High Water in the Mississippi (1868) renders the same plantation underwater. In this case, the same group of Black men, women, and children cling to the rooftop of a submerged house, desperately seeking safety. The visual dichotomy in the two artworks encapsulates post–Civil War socioeconomic hardships endured by Black people in the South as they faced natural disasters and systemic oppression. The image reflects the significant adversities these communities endured despite the end of slavery. The Mississippi River’s periodic flooding had devastating effects on the surrounding lowlands, which were the only property that many Black families could acquire at the time.[4] These floods led to the displacement of many, loss of property, and severe economic hardship that later affected the same communities during the Great Flood of the Mississippi River in 1927.

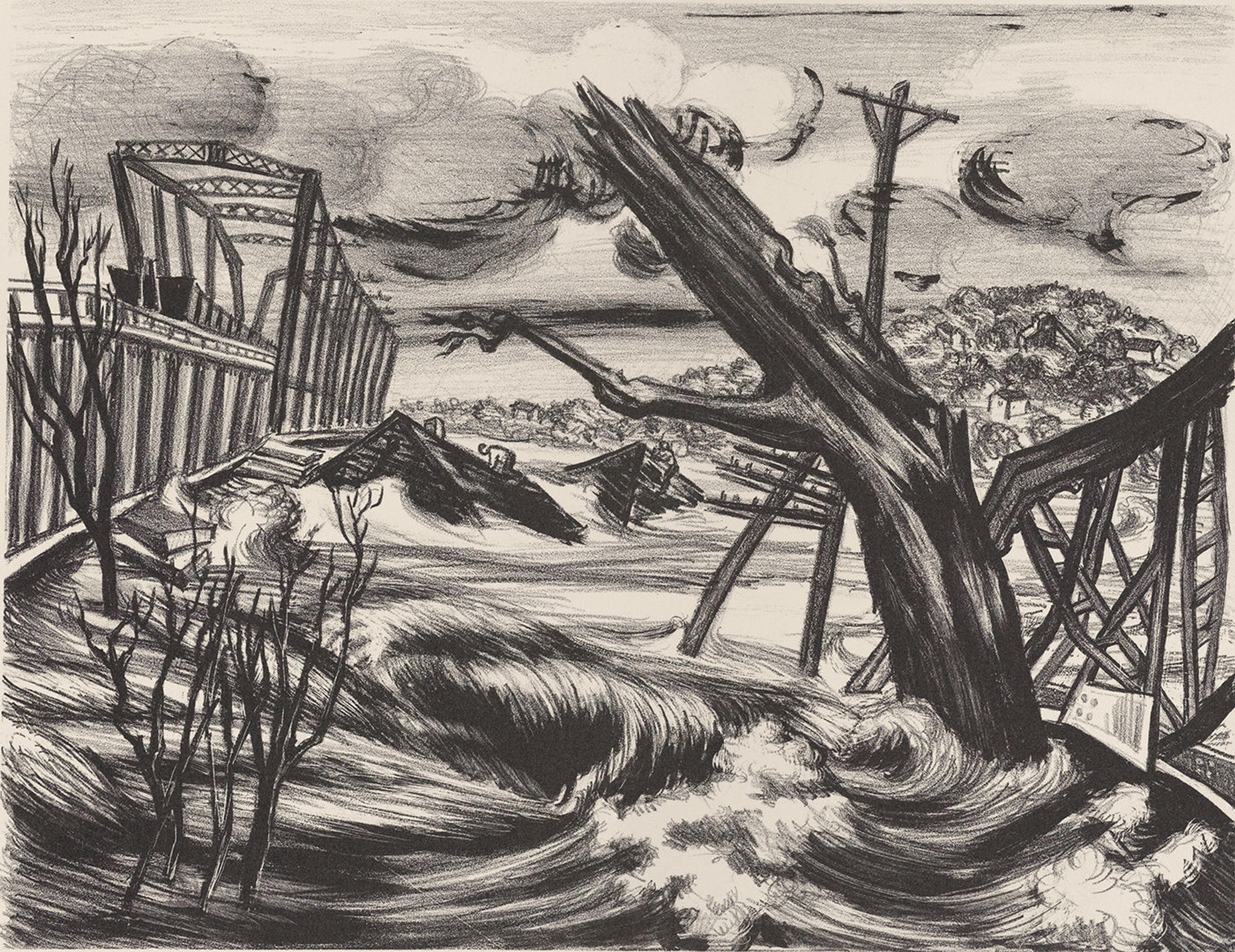

Jacob Kainen (American, Waterbury, Connecticut 1909–2001). Flood, 1937. Lithograph, 10 3/4 in. × 14 in. (27.3 × 35.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of New York City W. P. A., 1943 (43.33.395)

Between 1935 and 1943, artists engaged with the Works Progress Administration (WPA) also engaged with these disasters.[5] The Graphic Arts Division of the WPA employed more than two hundred printmakers, becoming a beacon of artistic production during the Great Depression. Jacob Kainen (1909–2001), a printmaker and art historian, illustrated the devastating floods in the Northeast in 1936. In the wake of the severe flooding in March of that year, cities like Hartford and Middletown in Connecticut lost electricity and telephone communication, and many inhabitants had to be rescued by boat.[6] Since these areas neighbored the artist’s native Waterbury, it is most likely that Kainen witnessed the tragedy and felt compelled to illustrate it. Made the following year, his lithograph Flood vividly portrays the violent overflow of river waters, sweeping away parts of a city’s infrastructure, with entire trees, utility poles, and rooftops carried away by the surging waters. At the same time, people cling to their homes’ roofs for survival. Kainen’s lithograph serves as a historical record and commentary on this catastrophe’s collective dimension and shared experience.

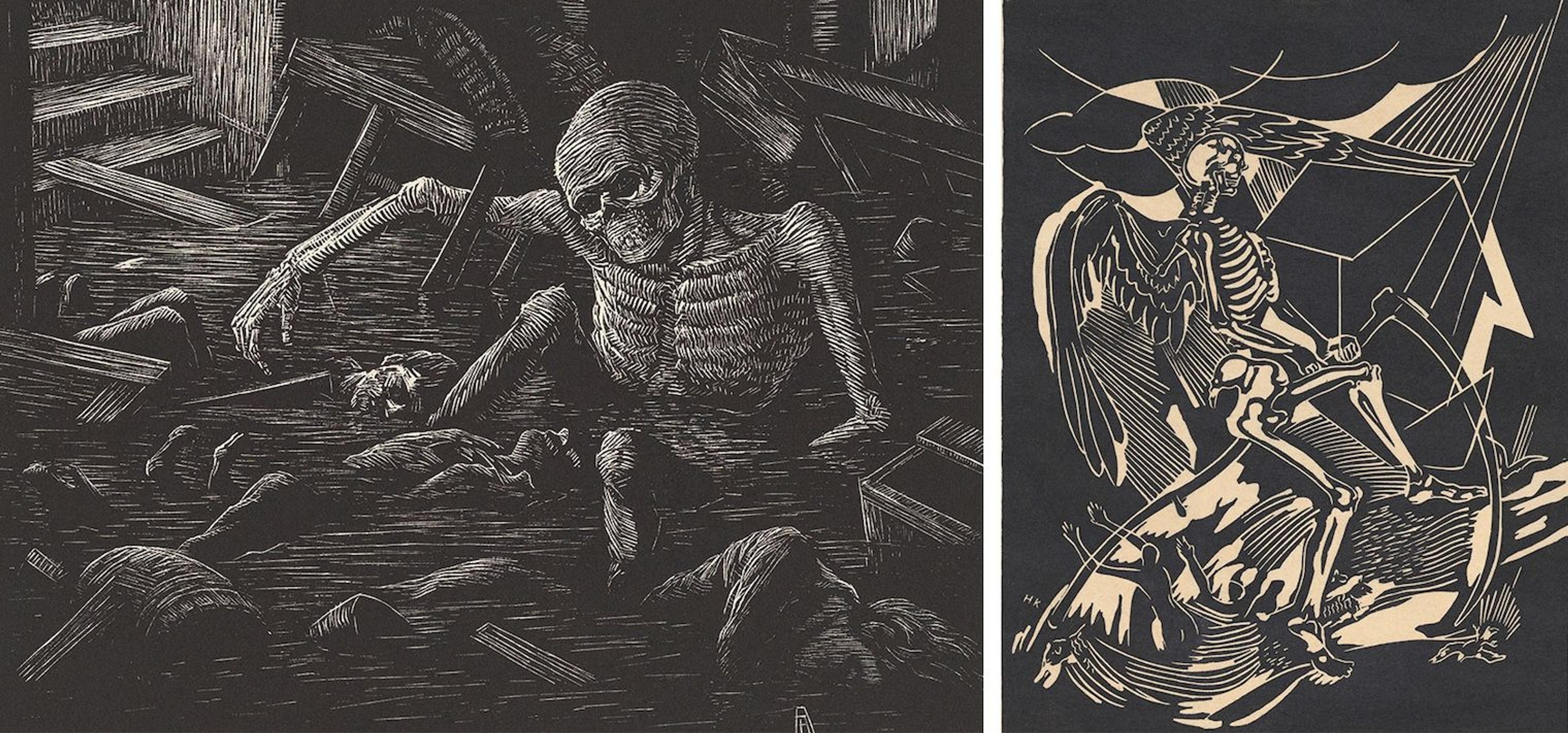

Left: Albert Abramovitz (American, 1879–1963).Flood, ca. 1938. Wood engraving, 4 1/2 x 6 in. (11.4 x 15.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of New York City W. P. A., 1943 (43.33.138) Right: Hilda Katz (American, Bronx, New York 1909–1997). The Flood, 15 × 11 1/2 in. (38.1 × 29.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Hilda Katz, in memory of Lina and Max Katz, 1965 (65.698.22)

In the 1930s, the United States experienced several other catastrophic floods, such as the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 and the Los Angeles Flood of 1938. Deluges occupied residents’ minds nationwide, and some artists focused on metaphorical ways of representing the sorrow and loss during these years. Albert Abramovitz (1879–1963), who migrated from Russia and had lived and worked between New York State and California during the 1930s, witnessed these disasters and dedicated more than one artwork to the subject.[7] The artist, known for his stark social commentary, frequently used skeletons and skulls to symbolize the prevalence of death and destruction. His wood engraving titled Flood (ca. 1938) shows the waterlogged interior of a home. Amidst the floating furniture and debris, three lifeless bodies drift in the water—including a prominent skeletal figure in the foreground. Years later, in 1949, Hilda Katz (1909–1999) made her linocut, The Flood, also using a prominent skeleton as a compositional element to symbolize the sorrow of the natural disaster. Katz reinforced this morbid theme by depicting an angel of death holding a scythe in his left hand. The emptiness of the background, adorned solely with a house in the shape of a barn, suggests a rural setting, possibly alluding to the 1949 New Year’s Flood in the Northeastern United States.[8] Katz’s work blends religious symbolism with the harsh realities of natural disasters, highlighting the existential threat floods pose to rural communities.

Edgar Imler (American, Clairsville, Pennsylvania 1896–1973 Altoona, Pennsylvania). Flood, ca. 1937. Wood engraving, 6 × 8 in. (15.2 × 20.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of New York City W. P. A., 1943 (43.33.98)

The sense of victimhood and the collective experience of these natural disasters were represented by other artists such as Edgar Imler (1896–1973), a painter and engraver who created a wood engraving called Flood (1937) based on the St. Patrick’s Day Flood of March 1936 in Pennsylvania.[9] Imler’s depiction focuses on a family’s frantic escape from their flooded home. The somber scene features a woman handing a child to another woman for safety while a man paddles furiously to steer a fragile driftwood. This engraving captures the desperation of individuals trying to save their loved ones amidst rising waters. The engraving’s detailed rendering of the floodwaters and debris further enhances the sense of peril and urgency.

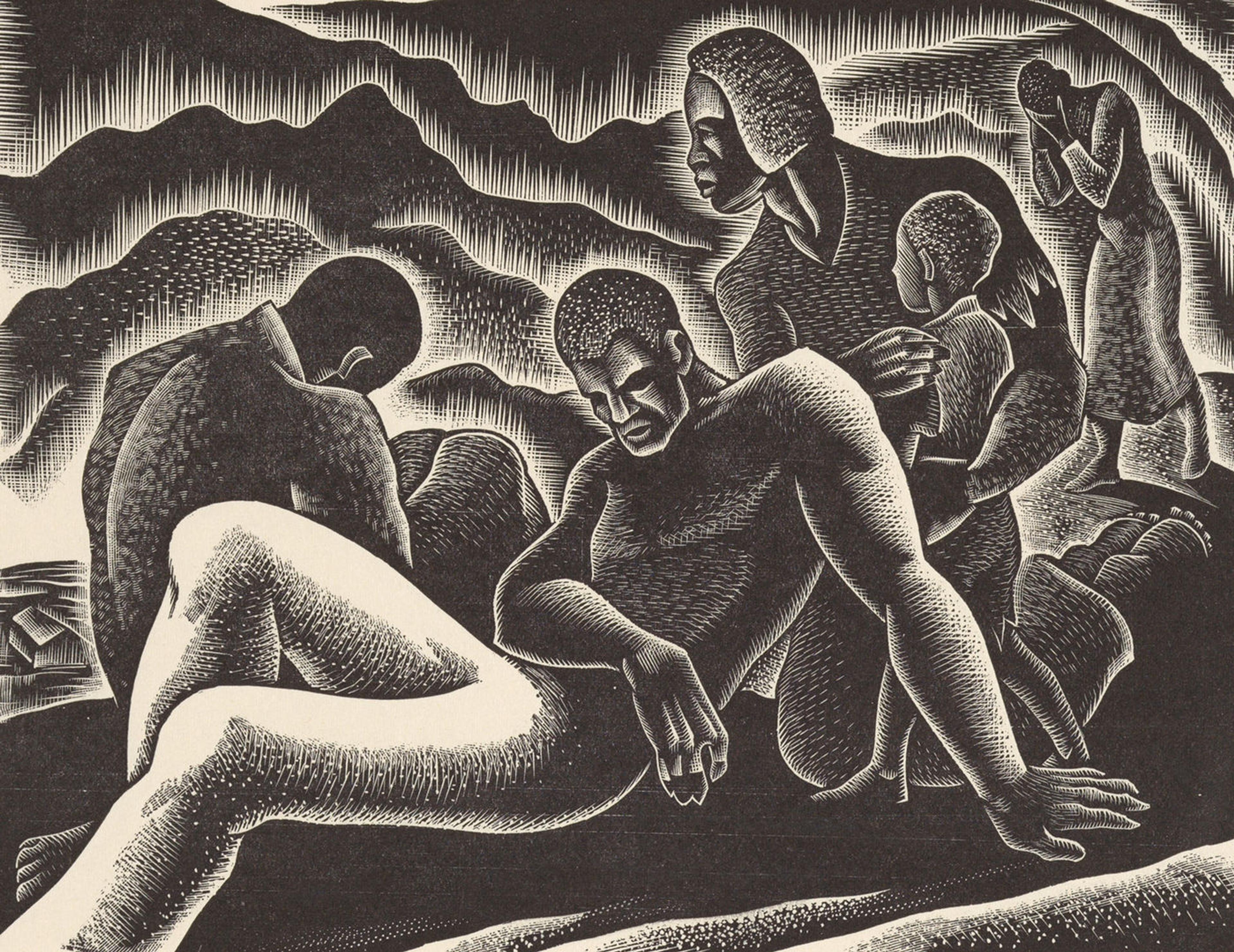

Donato Rico (American, Rochester, New York 1912–1985 Hollywood, California). Flood Victims, ca. 1938. Wood engraving, 4 3/4 x 6 1/4 in. (12.1 x 15.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of New York City W. P. A., 1943 (43.33.3)

Dan Rico (1912–1985), a versatile artist and caricaturist known for his work under various pen names, created a wood engraving titled Flood Victims in 1938 that depicts a group of Black flood survivors. Unlike other dramatic portrayals of natural disasters, Rico’s piece focuses on the quiet aftermath. The image shows a family fleeing the inundated landscape in the background, with hints of the event’s devastation visible on the lower left side of the composition. The sorrowful facial expressions of the male and female figures at the center reflect the dire consequences of the flood. The survivors lie exhausted on the ground, their demeanor conveying sorrow and fatigue. This engraving, made a decade after the Great Flood of the Mississippi River in 1927, is notable for its subdued and contemplative tone. That flood had a particularly devastating impact on Black communities in the Mississippi Delta, where many were left destitute and without shelter, and their representation here as victims of such disasters emphasizes the systemic inequalities that exacerbate their suffering.

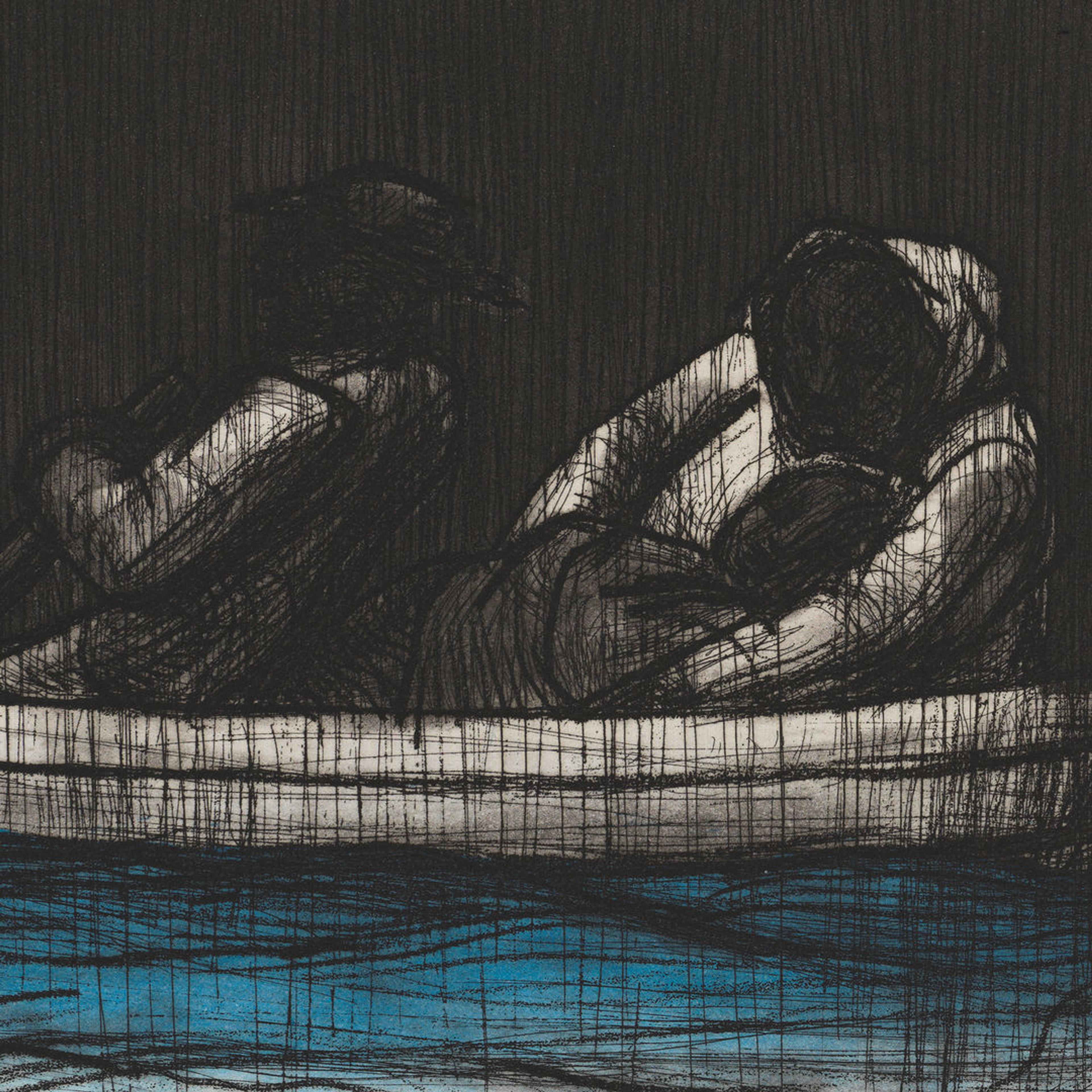

John Wilson (American, Roxbury, Massachusetts 1922–2015 Brookline, Massachusetts). Journey of the Mann Family, from "The Richard Wright Suite", 2001. Etching with aquatint, 12 × 16 in. (30.5 × 40.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 2023, (2023.264a). Courtesy of the Estate of John Wilson

In more contemporary representations, artists like John Wilson (1922–2015) have approached flooding using intaglio printmaking techniques—such as etching or aquatint—to achieve a grim ambiance in specific artworks. The influential African American novelist and poet Richard Wright (1908–1960) was an essential source of inspiration for the artist. Growing up in Natchez, Mississippi, Wright had firsthand experience with the contentious racial relations in the South under the Jim Crow laws and expressed such hardships through his stories. Wright’s collection of short stories titled Uncle Tom’s Children (1938) made Wilson feel a sense of “brotherhood” for the struggles of Black people in the South.[10] In 2001, the artist illustrated the short story “Down by the Riverside,” compelled by “Wright’s vivid dramatic setting.” This story, which juxtaposes the dangers of natural disasters and violent racist actions, follows the misfortunes of an African American family escaping the Great Flood of the Mississippi River while trying to get medical attention to a pregnant woman. The first illustration, titled Journey of the Mann Family, encapsulates the story’s premise by showing Brother Mann and Lulu, along with two other characters, on a boat amid a harsh downpour, rushing to the hospital as Lulu is about to give birth. The black ink that Wilson used to color the storm’s dark atmosphere echoes the characters’ fragility and solitude as they face the calamity. Wilson thought profoundly about the relation between technique and subject matter for this series: “Etching techniques like aquatint and spit biting were ideal to interpret the dark brooding, murky atmosphere. Above all, the river with its powerful currents and its violent energy lends itself to aquatint.”[11]

Nina Jordan (American, born 1964).Untitled, Flooded Home V, 2021. Color woodcut, 11 1/2 in. × 18 in. (29.2 × 45.7 cm). Gift of Katherine Beinecke Michel, 2023 (2023.176.2) © 2021 Nina Jordan

Using a different approach, Nina Jordan (b. 1964)—a Brooklyn-based painter and printmaker—has dedicated her career to exploring themes of shelter and safety in contemporary life through woodcut prints. The artist portrays homes and their socioeconomic implications, mainly focusing on individual access to housing and emotional attachments to living spaces. In this sense, Jordan makes the struggle to secure housing in the United States visible. Over the years, her work has evolved to address the impacts of climate crises, specifically through a series of color woodcuts that render houses submerged in floodwaters. These images, sourced from various news outlets, portray the potential for disaster across the United States and highlight the individual losses associated with such events. Interestingly, Jordan’s depictions often show empty houses, prompting viewers to consider the aftermath of natural disasters and the power of water to displace individuals and communities.

The artist’s creative process involves using found timber as the matrix for her woodcuts that evoke foundational housing material.[12] This method underscores the broader ecological and socioeconomic implications of climate-related disasters, raising critical questions about shelter in the context of global warming and climate change. Jordan’s interest in the subject was also sparked by the impact of these events on animals, which she added in some of her compositions to emphasize the disruption of ecological balance further. Her work ultimately connects the physicality of constructing a house with the found timber used in her woodcut matrices, creating a profound commentary on the intersection of materiality, shelter, and survival in contemporary society.

The artworks made by these printmakers provide a vivid tapestry of the impact of flooding in the United States, highlighting the intersections between natural disasters and systemic inequalities from the end of the Civil War to the present. These representations serve as historical documentation and social commentary, urging us to address the underlying issues that exacerbate the vulnerability of specific populations to flooding and, by extension, other natural disasters. Some of the illustrations serve as invitations to revisit stories and narratives about flooding, providing examples of some of the systemic problems in the history of the United States. As we face the ongoing and worsening threat of climate-induced disasters, it is essential to address the underlying issues that contribute to the vulnerability of marginalized communities and work toward a more equitable and resilient future for all.

Notes

[1] Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation, “Extreme Weather and Coastal Flooding: What Is Happening Now, What Is the Future Risk, and What Can We Do about It? Field Hearing before the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation, U.S. Senate, One Hundred Fifteenth Congress, First Session, April 10, 2017. - New York University - New York” (U.S. Government Publishing Office, April 10, 2017).

[2] NOAA National Severe Storms Laboratory. “Flood Basics.” Text. Accessed July 14, 2024. https://www.nssl.noaa.gov/education/svrwx101/floods/.

[3] Charlotte Streifer Rubinstein, Fanny Palmer: The Life and Works of a Currier & Ives Artist, First edition. (Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press, 2018), 144–45.

[4] John M. Barry, Rising Tide: The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 and How It Changed America, A Touchstone Book (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1997).

[5] As part of the New Deal (1933–38) enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the Works Projects Administration (WPA) was created as an agency to employ millions of people to execute public projects related to infrastructure, housing and the development of the arts. O’Connor, Francis V., ed. The New Deal Art Projects; an Anthology of Memoirs (Washington: Smithsonian Institution, 1972), 12.

[6] NOAA US Department of Commerce, “Historic Flood March 1936” (NOAA’s National Weather Service), accessed June 28, 2024, https://www.weather.gov/nerfc/hf_march_1936.

[7] Albert Abramovitz was born in Riga, Latvia in 1879 and started his artistic career studying Fine Arts in Odessa. He worked for a while in Odessa and migrated to the United States in 1916. After traveling on the West Coast, he settled in New York and was an active member of the WPA Graphic Arts Division in the 1930s.

[8] NOAA U.S. Department of Commerce, “Historic Flood January 1949” (NOAA’s National Weather Service), accessed June 28, 2024, https://www.weather.gov/nerfc/hf_january_1949.

[9] Bernadette A. Lear, “Pensylvannia Public Libraries and the Great Flood of 1936,” Pennsylvania Libraries: Research and Practice Vol. 2, no. No. 2 (Fall 2014): 113–28.

[10] Richard Wright, Down by the Riverside (New York: The Limited Editions Club, 2001).

[11] Afterword, Wright.

[12] Zoom conversation with the artist Nina Jordan on April 16, 2024.