How to Read Medieval Art by Wendy A. Stein features 141 full-color illustrations and is available at The Met Store and MetPublications.

«The intensely expressive art of the Middle Ages was created to inspire, educate, and connect the viewer to heaven. Its power reverberates to this day, even among the secular. However, understanding these works of art requires knowledge of the narratives depicted in them. I sat down with author Wendy Stein to learn some of the meaning behind these images and uncover the value of looking closely.»

Rachel High: There are many medieval works in The Met collection, but this book covers a selective group. Why did you choose these particular objects to teach readers how to understand other medieval objects in both The Met collection and in general?

Wendy Stein: Unlike other books in the How to Read series, this is really a book about the stories that are depicted in medieval art rather than the evolving styles. I was looking for objects that would be illustrative of the principal stories, so at first I was focusing more on the key narratives rather than the key objects. When I established those major stories, I looked for objects that best illustrated them while representing masterpieces in our collection. I also was specifically looking for single objects that had multiple scenes, which could tell a whole cycle of stories.

This reliquary shrine honors the Virgin Mary and includes depictions of scenes surrounding the birth of Jesus. Attributed to Jean de Touyl (French, died 1349/50). Reliquary shrine, ca. 1325–50. French, Paris. Gilt-silver, translucent enamel, paint, Overall (open): 10 x 16 x 3 5/8 in. (25.4 x 40.6 x 9.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1962 (62.96)

Rachel High: As you've alluded to, the book is made up of five sections addressing different themes of medieval art. How did you arrive at these categories?

Wendy Stein: I wanted there to be an arc from simply identifying the most basic stories that would have been well-known to all viewers in the Middle Ages to not just identifying a particular scene, but using the evolution of that scene to illustrate more subtle and intellectually rich historical, theological, and sociological concepts. The book starts with a chapter addressing foundation stories and goes into more detail from there, including secular imagery.

The Unicorn Tapestries are well-known examples of medieval secular art in The Met collection. The Unicorn in Captivity (from the Unicorn Tapestries), ca. 1495–1505. South Netherlandish. Wool warp with wool, silk, silver, and gilded wefts, Overall: 144 7/8 x 99 in. (368 x 251.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of John D. Rockefeller Jr., 1937 (37.80.6)

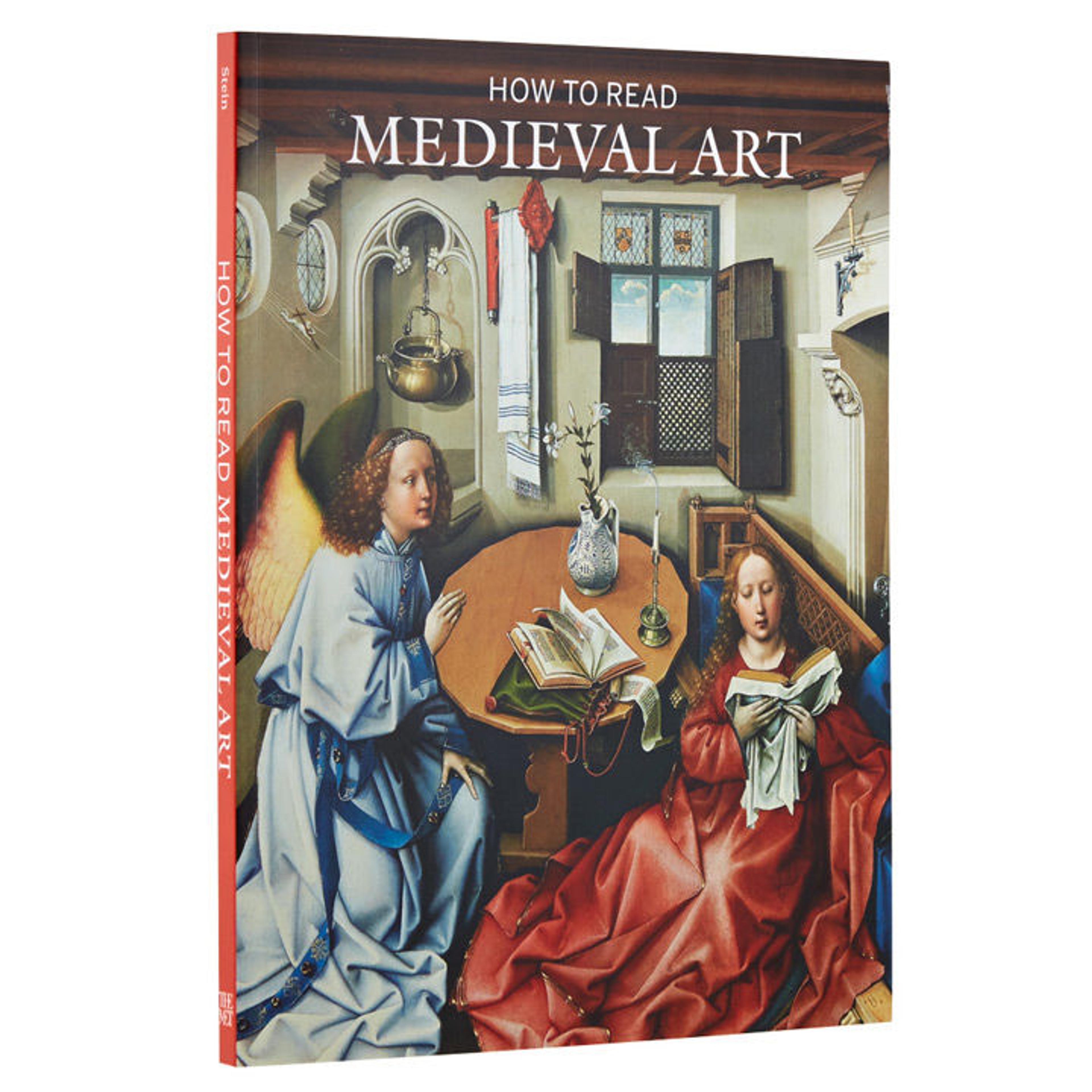

Rachel High: The How to Read series is an appropriate format for this topic since so much of medieval art focuses on symbolic objects or poses that communicated certain details to the medieval viewer. Could you give a reading of the detail of the central panel of the Merode Altarpiece that is shown on the cover of the book?

The Merode Altarpiece is a masterpiece of The Met collection and is on view at The Met Cloisters. A detail of the central panel is the cover of How to Read Medieval Art. Workshop of Robert Campin (Netherlandish, ca. 1375–1444). Annunciation Triptych (Merode Altarpiece), ca. 1427–32. South Netherlandish, Tournai (present-day Belgium). Oil on oak, central panel 25 1/4 x 24 7/8 in. (64.1 x 63.2 cm), each wing 25 3/8 x 10 3/4 in. (64.5 x 27.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1956 (56.70a–c)

Wendy Stein: This image is a very typical representation of the Annunciation: the moment when the archangel Gabriel comes to tell the Virgin Mary that she will bear Jesus. The angel is making a speaking gesture and the Virgin is listening, but this picture has so much more going on. For example, the humility of the Virgin is emphasized by her being seated on the floor. The scene is represented as a domestic interior that would have been very familiar to anyone of the time. The furniture, the brass basin, the jug on the table, the candlestick, the windows and their shutters, the beams of the ceiling—all of these elements would be very typical in a Flemish household of the period. The artist causes the viewer to identify with this incredibly fundamental theme of Christian history and theology by setting it in an environment that is familiar to him or herself.

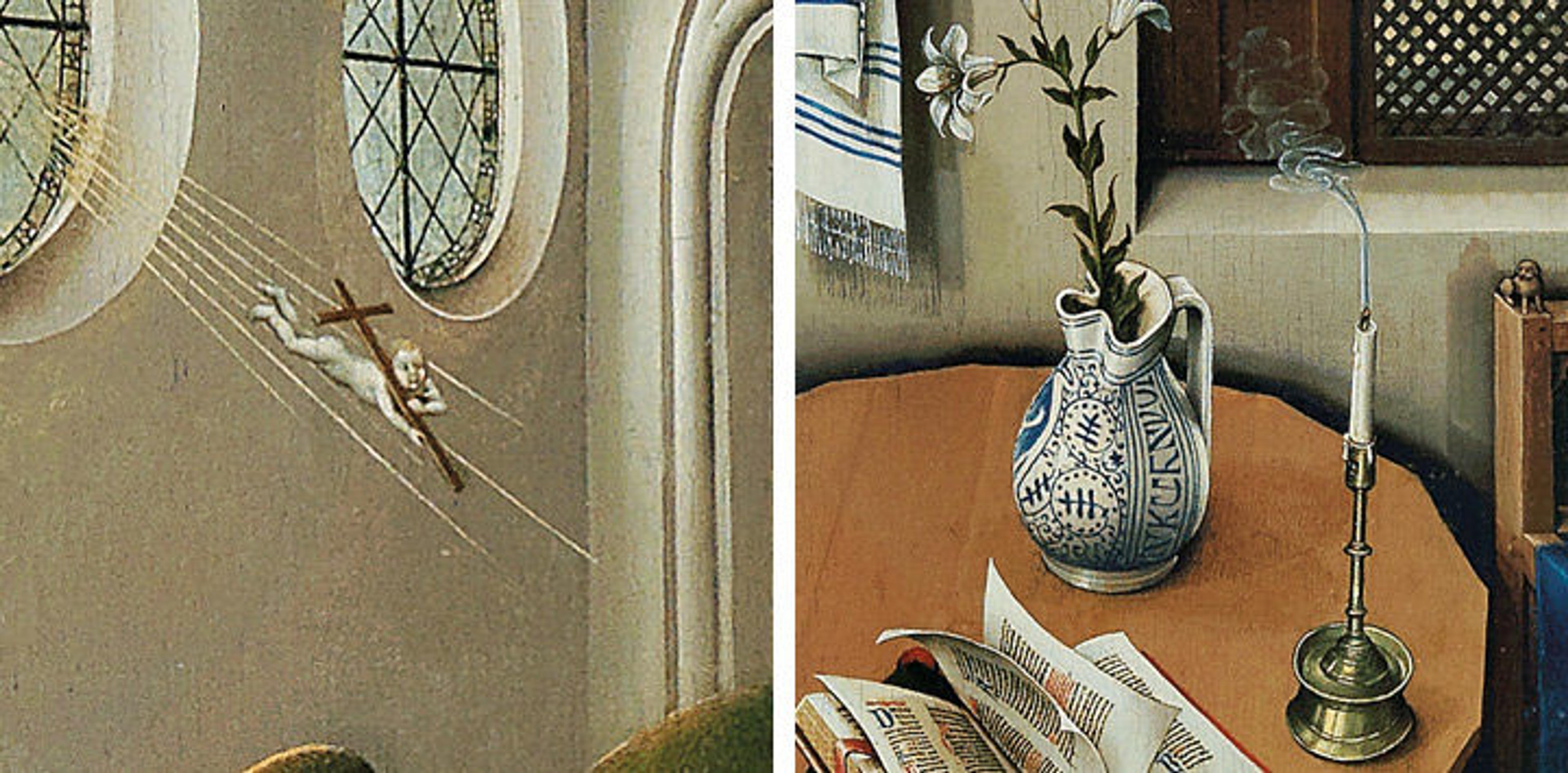

This is one of The Met's great masterpieces, but many people who have seen this work never notice this particular detail that I just love pointing out to them: a tiny image of an infant carrying a cross and riding into the room on golden beams. This baby represents the infant Jesus at the moment of the incarnation and is shown here instead of the dove of the Holy Spirit, which is more traditionally depicted in Annunciation scenes. This figure also represents divine light, and since divine light is coming into the scene at that moment—poof—the earthly light of the candle on the table goes out and you just see smoke.

Details of the Annunciation Triptych (Merode Altarpiece)

Rachel High: A lot of art historical conventions and iconography originate in the medieval period. Do you think learning how to read medieval art enriches one's understanding of art, perhaps even into the present day? If so, how?

Wendy Stein: There's no question that learning how to read medieval art hugely enhances one's reading of later art. I think that the answer to this question goes back to something much more basic, which is taking time to look at works of art and to know the story that is being depicted. Just taking time is fundamental to enjoying any art. I think that all of the How to Read series show that the experience of looking at art will be enhanced by taking the time to really read it—to think of looking at a work of art as a journey through an object and not just a passing glance.

Related Event

How to Read Medieval Art Talk + Signing

Friday, December 16, 6:30–7:30 pm

The Met Fifth Avenue - The Met Store

Free with Museum admission