I’d traveled to Italy to learn to weep. Standing before Piero della Francesca’s fresco of Saint Julian the Hospitaller, as I listened to the story of the saint, my face became overrun with the aftermath of a levee breaking. At first blush, the juvenile resembles a young aristocrat. The rich depth of his red cloak suggests wealth, the underside of his hat forming a golden halo. Yet, his look is as bewildered as any teenager that I've ever encountered in a cell. He might as well have been wearing handcuffs.

I wept as I listened to the young man’s story. He’d traveled many miles from his home to avoid a disaster. A stag had prophesied that Julian would murder his parents, and Julian had believed that distance would abate disaster. But many years later, his parents walked many miles to visit Julian and his wife. In the fields, Julian was unaware of his parents’ arrival. He did not know that his mother and father slept in the bed he’d left that morning for the fields and that his wife was working in the back garden. Saint Julian had imagined his wife engaged in adultery. Rage at betrayal deserted Julian when he discovered the bloodied bodies were not his wife and a lover, but his parents. After the killing, Julian and his wife would walk and walk and walk until building several hospitals on a riverbank.

He is the patron saint of those on a journey, those people who find themselves far from home, hoping for safe travel and a safe bed to rest in. I wept thinking of the many treks around prison rec yards I’d made with men whose crimes would never be forgiven, for whom freedom sometimes felt as unlikely as sainthood. And for men who found no reprieve on their journeys, no safety in the beds they slept.

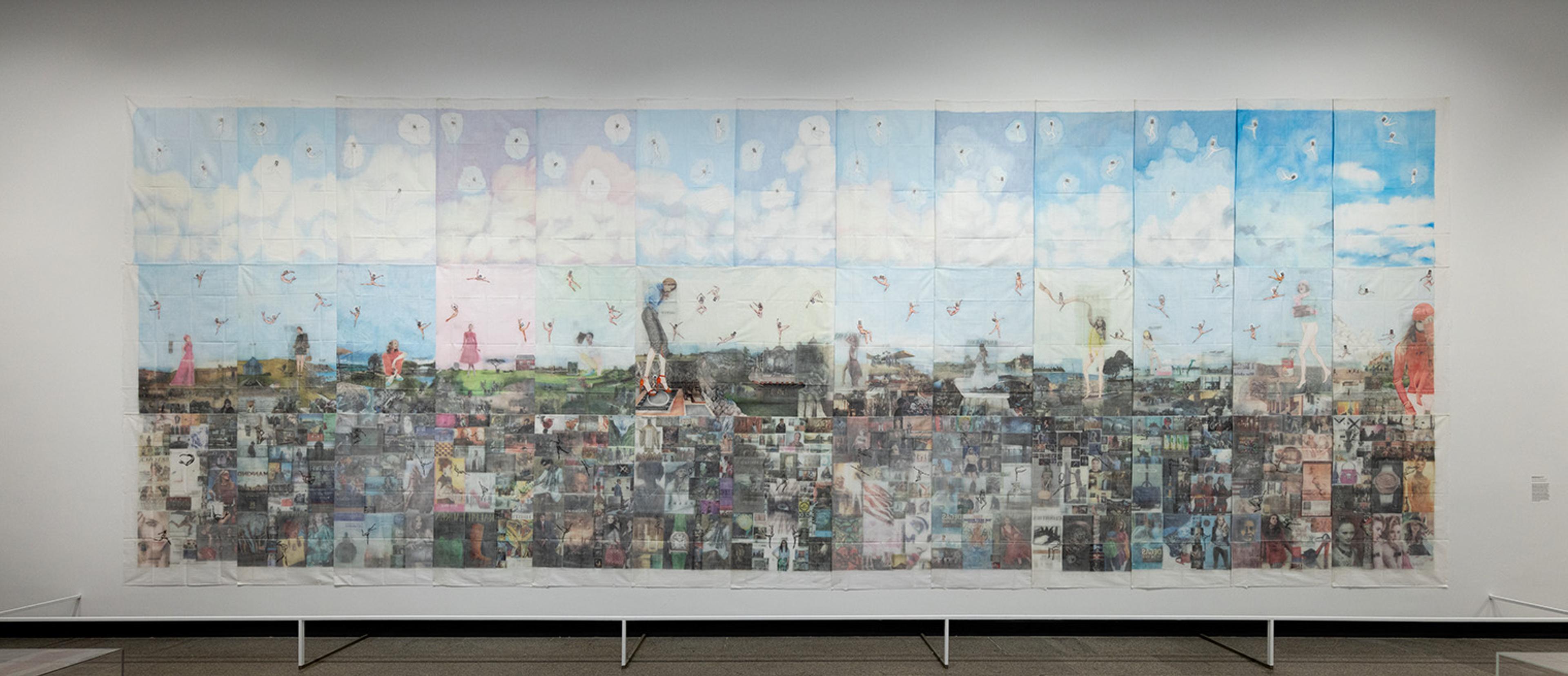

Left: Fresco fragment of Saint Julian the Hospitaller (1454–1458). Right: Jesse Krimes (American, born 1982). Apokaluptein:16389067, 2010–13. Cotton sheets, ink, gouache, colored pencil, hair gel, Overall: 15ft. (457.3 cm) x 40ft. (1219.5 cm). Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery (JK.02.a–mm)

Jesse Krimes is an ex-con, a felon, formerly incarcerated. All suggest he knows the sound of a cell door closing with him on the wrong side. And he knows the rumor: little good comes out of prison, and even less good is produced from inside the harrowing walls that reveal all the ways we run from justice in this country. And yet, as if to call a lie to the rumor, those inside have named the letters they write and receive kites, as if words alone can give a man wings—and what is more worthy of celebrating than all the ways we fly despite the burdens.

Krimes’s epic mural Apokaluptein:16389067 (2010–13) stretches fifteen feet high and forty feet wide. Each scene is crafted on half a bedsheet, using a process invented by Krimes, where he implemented hair gel to transfer images from The New York Times onto ripped squares made of half a sheet, transforming the sheets into kites, mailing one at a time from prison, almost as letters, reminding the world of our fractured existence.

Jesse Krimes (American, born 1982). Apokaluptein:16389067, 2010–13. Cotton sheets, ink, gouache, colored pencil, hair gel, Overall: 15ft. (457.3 cm) x 40ft. (1219.5 cm). Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery (JK.02.a–mm)

All these images that escape the lives of men and women serving time in the bing. I knew a cat inside who taught himself how to transform a Walkman into a tattoo gun, how to read schematics and repair anything broken in a prison cell, and how to make himself indispensable to men who lacked the money to purchase anything twice. Krimes’s ingenuity matches. Krimes was already an artist with a college degree when he arrived at FCI Fairton on a drug case, spent twelve hours a day for three years creating his funky rendition of calisthenics. With hair gel and a spoon—and with the patience of a man with a release date years away—he painstakingly transferred images from the magazines he collected onto the sheets in a makeshift monoprinting process, all the while imagining a landscape he couldn’t see, in the same way that he and those around him were imagining a freedom that on some nights felt out of reach.

The cosmology Krimes creates is like the meal made in prison. From state to state, the dish that is a smorgasbord of everything you can put your hands on that you find worthy is called a different name. We called it a swoll, and it might contain tuna, noodles, cheese crackers, and whatever we could pilfer from the kitchen. In the process, the layers would become less defined and more organic. An iconography of wild and absurd juxtapositions characterizes the layers of Krimes’s landscape as well: angels, pop figures, large red shoes, a smiling, suited, and pre-presidential Donald Trump, and so many dancing figures. It is the smashup of heaven and hell, saints alongside cartoons. And if there is a heaven in the layer, the flying figures must become a kind of kite, a touchstone to what might be possible amidst it all.

Installation images of Apokaluptein:16389067 at Eastern Correctional Center in 2014

Once released in 2014, Krimes showed the piece for the first time in America’s first prison, Eastern Correctional Center. For viewers, he wanted to take them into what it felt like to be in his cell for those years, living with Apokaluptein in his head. He created a cell within a cell, using wooden beams, drywall, plaster, and facsimile bricks. Then, he transferred the original images onto the wall, creating his own fresco of Apokaluptein, draped on the walls and ceiling of the cell he’d fashioned—his own Sistine Chapel, a replica of all that travels through a person’s mind desiring to leave prison as something other than as he’d walked in. The decision says something about Krimes’s vision, but also echoes how prison will not let some of us go.

I first saw the piece months later at an exhibition at Rutgers University. Recently, seeing it again, I began to wonder if the point of prison, of talking about prison, wasn’t as much about perseverating on what won’t let you go, as much as finding a new word to explain the nuance of prison’s lingering. Years ago, reading Letters from Canto Mundo, I discovered the word petrichor. As a child, the one moment that truly enchanted me, like José Arcadio Buendía discovering ice for the first time with his father, was one of those summer rains, when a step took you out of a downpour and into the sunshine. Petrichor is that pungent, earthy smell you get when walking into the aftermath of the rain. And it’s the thing that you have to notice, and noticing it cannot exist without first experiencing the rain. In the work of Jesse Krimes, the rain that prompts the majesty and discovery that follows it is incarceration. But the thing that follows is whole cloth a new invention, like ice or petrichor. The work becomes a way to both evaluate what was known before it and to discover something distinctly new.

Installation of Apokaluptein:16389067 (2010–13) and Naxos (2023–24)

This year at The Met, I saw Krimes’s Apokaluptein for the second time, juxtaposed with Naxos (2023–24). The latter is different, Krimes working at scale on a wildly distinctive level. It’s a piece that is less the landscaped, fractured narrative of Apokaluptein and more the abstraction of a Buddhist stone garden. I went to prison at sixteen, and I only mention it now because during those years, I never stood on a riverbank and skipped a rock, nor paused to pick up a stone as I walked as many miles around gravel as Saint Julian did on his way to becoming the Hospitaller. Krimes’s work reminds me of Piero della Francesca’s fresco because it is always the story of someone seeking to outpace their past. The production of Apokaluptein, even, is its own kind of labor—the work of an artist turned into the labor of redemption? On some level, it seems a hokey proposition: art, no matter how beautiful, is in no way comparable to Julian building his first hospital atop the stones on the edge of a riverbank. Yet perhaps the purpose is that Krimes’s work invites you to think of prison as less homogeneous and more complexly fractured, disjointed, and capacious than previously noticed.

Jesse Krimes (American, born 1982). Purgatory, 2009. Soap, ink, and playing cards [offset lithography], Variable; Image (Soap): approximately 1 1/2 in. × 1 in. (3.8 × 2.5 cm), each Playing cards: approximately 3 1/2 in. x 2 1/2 in. (8.9 x 6.4 cm), each. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Vital Projects Fund Inc. Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, and Alfred Stieglitz Society Gifts, (2024.327.1–.291)

Naxos demands a different kind of attention than any of Krimes’s earlier work. In The Met’s display, you see Krimes moving through different levels of scale, from the soap cast portraits in playing cards of Purgatory (2009) to Apokaluptein, but it is in Naxos where the scale shifts the narrative. With ten thousand small stones, each chosen by a person currently incarcerated and suspended by just as many threads of string as thin and nearly translucent, a viewer experiences something visceral, a metaphor for being incapable of holding the entire story of the penitentiary in any single narrative. Elizabeth Alexander writes that Black people are not one or one thousand things, and here Krimes says the same of the thousands of people who paced a prison yard searching for the singular pebble to represent themselves in his art.

Jesse Krimes (American, born 1982). Naxos, 2024. Mixed media (including pebbles, thread, and pins), Overall: 14 × 39 ft. (426.7 × 1188.7 cm) [with the 39 panels installed in 3 rows of 13]. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery (JK.04)

To stand before Naxos is to experience what proximity requires. To see the whole is not a matter of vision or eyesight, but impossibility. You are too close, literally, no matter where you stand. Standing before the epic, the only stones you will see are those clusters that do not exceed your periphery. This is the argument for how proximity to those who suffer and experience joy in prison actually happens, not by contemplating the whole but by realizing that the whole is an accumulation of more individual narratives than can ever be named. Naxos’s abstraction tells the story of so many men and women I weep for, whose lives have become the homogenous depiction of incarceration, whether at the hands of those who strip us of our individualism through their calls for abolition or those who condemn us with their calls for three strikes. This painstakingly conceived work—the more than ten thousand stones collected from men whose names we do not know—says that we cannot ever imagine the treks around a gravel path these men and women have paced to become Saint Julian, and how often the penitentiary allows for the penitence, but maybe does not allow enough for the possibility that a person whose known violence might become a saint.