A new display of paintings and luxury objects in the Islamic galleries at The Met Fifth Avenue focuses on the centuries-long artistic exchange between India and Europe. Twelve important historical jewels from the Benjamin Zucker Family Collection, all of which contain Indian diamonds, join the Company School paintings (paintings from British India) on view in gallery 464. The jewels on display, which include a recent gift to the Museum, illustrate the international trade of diamonds from India and evolving tastes in fashion, as well as technological advances that facilitated innovative faceting techniques and styles.

Clockwise from top: View of the installation in gallery 464. Photo by Sumi Hansen. Rose-cut diamond brooch (detail), late 17th century. Netherlands. Benjamin Zucker Family Collection. Gold ring with octahedral diamonds, 11th- to 13th-century. Pakistan or Afghanistan. Benjamin Zucker Family Collection

History and Myth

Until diamonds were discovered in Brazil in the early eighteenth century, the vast majority of the world's diamonds were found in India. These precious Indian gemstones were mined primarily in alluvial deposits, such as rivers and other bodies of water, where they came to rest after pushing through the surface of the earth millions of years ago.

Indian diamonds were famously traded to other parts of the world, particularly the Middle East and Europe. Evidence of diamond trade to Greece is found as early as 315 BC in the Greek author Theophrastus, who mentions stones known as adamas, meaning invincible, or indivisible.

The difficulty of obtaining diamonds perhaps led to the best-known origin myth of these coveted stones, the legend of the Valley of the Diamonds. This myth was documented as early as the fourth century by Ephiphanius, Bishop of Constantia in Cyprus (ca. 315–403).

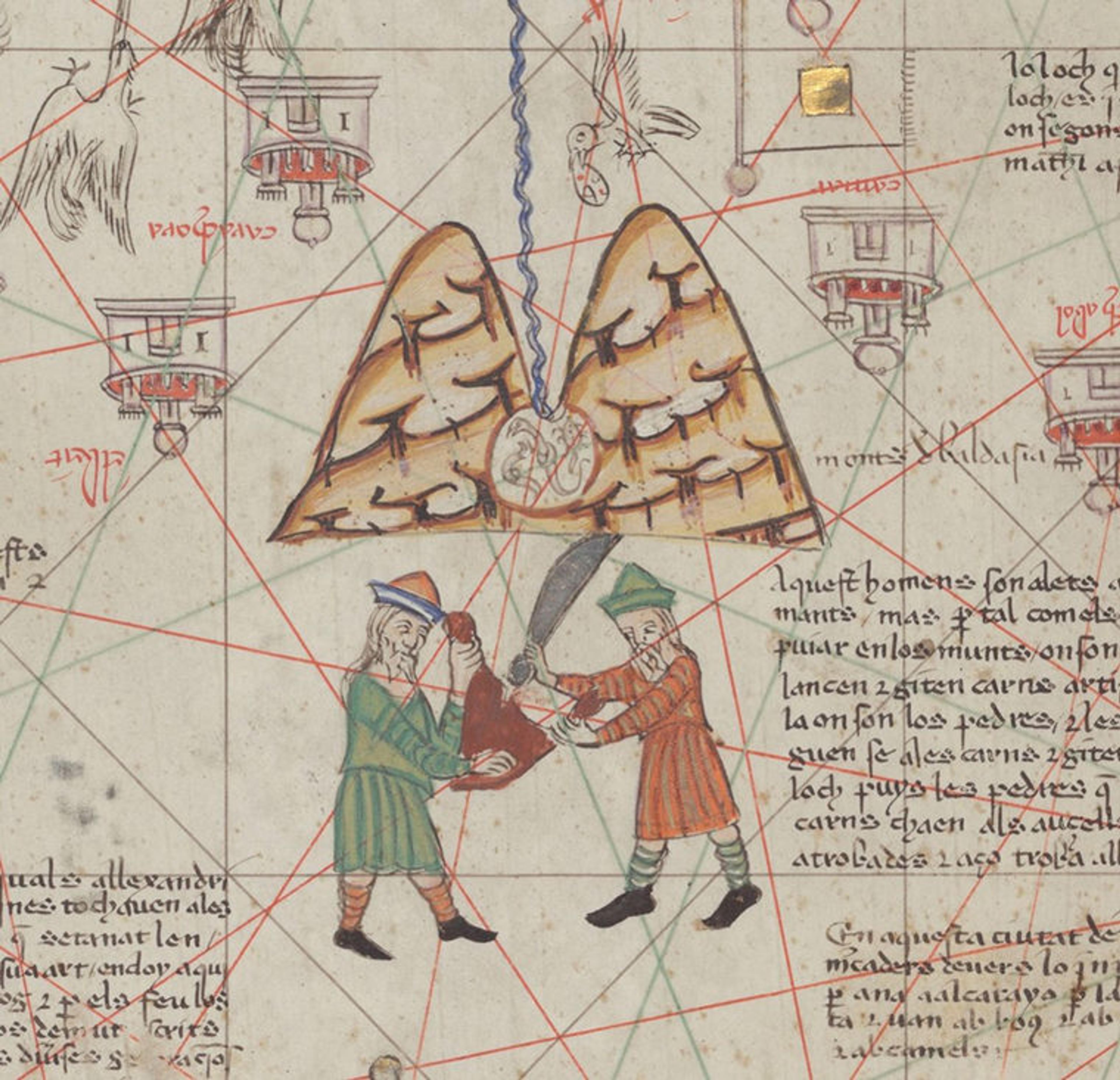

Detail from view 12 of the Atlas of Nautical Charts(Catalan Atlas) by Abraham Cresques, ca. 1370–80. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Département des Manuscrits. Espagnol 30. Source: gallica.bnf.fr

The bishop describes a deep, dangerous, and inaccessible valley, full of precious gemstones. In order to obtain these valuable treasures, miners throw chunks of fresh meat into the valley so that they are pierced by the sharp gemstones lying at the bottom of the gorge. Attracted by the scent, eagles swoop down to retrieve the flesh. Relocating the flesh to more accessible terrain, they separate out the gemstones as they consume the meat.

This myth can be found in diverse sources, from Chinese Tang (618–907) and Song Dynasty (960–1279) histories, to Persian and Arabic medieval sources, to the adventures of Marco Polo (1254–1324) and Niccolò de' Conti (c. 1395–1469). With each retelling, certain details evolve, such as the specific location of the valley and the presence or absence of poisonous serpents guarding the gemstones. In some cases the tale is associated with Alexander the Great (336–323 BC), who is sometimes reported to have discovered the valley.

A fourteenth-century atlas made in Mallorca (above), which illustrates the Valley of the Diamonds, identifies the region as India. The crevasse is full of snakes, and two figures nearby slice red flesh to attract a vulture flying overhead. The mythical geography of the Valley of the Diamonds was also used to represent the region of India in several illustrated texts reaching as far as the Ottoman Empire, as seen in a sixteenth-century world history, the Maṭāli˓ al-sa˓āda wa manābi˓ al-siyāda.

Octahedral Diamonds

Rough octahedral diamonds in an eleventh- to thireenth-century ring from Pakistan or Afghanistan. Benjamin Zucker Family Collection

How were Indian diamonds cut and worn? The extreme hardness of diamond makes it exceptionally difficult to cut, and early jewelry featuring this stone incorporates uncut crystals in their most common natural form, the octahedron.

The earliest jewel in our display, a gold ring that may date as early as the twelfth century, is set with three incredibly limpid octahedral diamonds (above). This ring has been attributed to the treasury of Mu'izz al-din Muhammad bin Sam (r. 1173–1206), a ruler of the Afghani-based Ghurid dynasty (early eleventh century to 1215). In their late twelfth-century expansion, the Ghurids entered northern India and took control of the Panna diamond mines in modern-day Madhya Pradesh. The Ghurid treasury was reported to have contained hundreds of pounds of diamonds, all of which came from Indian mines.

The Indian preference for uncut stones is emphasized in ancient Sanskrit texts as early as the Arthashastra, from the fourth century BC. For this reason, some of the oldest jewels with Indian diamonds feature well-formed, uncut stones. Symmetrical, colorless, and very limpid octahedral crystals, such as the ones seen in this ring, were thought to be the best type. For centuries, stones in this form were traded to Greece, France, and Italy, where too they were set uncut in jewelry and jeweled objects.

Point-Cut Diamonds

By the fourteenth century, lapidaries in Europe were using diamond powder to polish gemstones. By grinding a diamond against a lead plate covered with diamond dust, they could eliminate surface imperfections and shape the octahedral faces. This manipulation led to "point-cut" diamonds. Point cuts maintain the silhouette of an octahedron but enhance the faces of the diamond into smooth, even surfaces. Lapidaries at this time were likely aware of the unique directional variations in the material's strength. Parallel to the octahedral faces is the cleaving direction, a "grain" in which the gemstone can split relatively easily and evenly. Cleaving the faces of the gem could remove flaws on or near the surface of the stone, and shape it into a flawless form.

Left: Point-cut diamond ring, 16th century. Venice. Benjamin Zucker Family Collection. Right: Fragment of a textile with Medici emblems, including a point-cut diamond ring, ca. 1492. Italian. Silk, metal thread, 13 1/2 x 12 5/8 in. (34.3 x 32.1 cm), including fringe. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Fletcher Fund, 1946 (46.156.70)

By the fourteenth century, a ring set with a single point-cut diamond became a popular piece of jewelry in Europe. Around this time, the iconic single-diamond form became a known emblem found in family crests, including that of the influential Florentine Medici family (above right). The hardness and durability of diamond has long been recognized as a symbol of fortitude, endurance, and valor—characteristics many powerful individuals wished to be identified with. An exquisite sixteenth-century Venetian ring (above left) from the Zucker collection is a variation on this style, with five point-cut diamonds.

Table-Cut Diamonds (and More)

Ring with seven table-cut diamonds. England, 17th century. Benjamin Zucker Family Collection

Like point-cut diamonds, table-cut diamonds were known by the end of the fourteenth century. The table cut is a modification of the octahedron, with the top of the pyramid evenly removed to create a large facet on the top of the stone, known as its "table." This cut, shown in the ring above, facilitates even more light refraction and reflection, thereby increasing the brilliance and luster of the stone.

Left: Rose-cut diamond brooch (detail), late 17th century. Netherlands. Benjamin Zucker Family Collection. Right: Nell Gwynne bodkin with brilliant-cut diamonds (detail), 17th century. England. Benjamin Zucker Family Collection

In the late fifteenth to early sixteenth century, technological advances in cutting techniques—namely, the introduction of a spinning wheel known as a scaife—industrialized the faceting of gemstones. From that moment on, new cuts, such as the rose cut and brilliant cut (see above), came to be known in European jewelry.

The Journey of the Stones

The diamonds on view in this small display tell an important story of the trade from Indian mines to Europe. Records indicate that from the eighth to sixteenth century, the gemstone trade routed rough Indian stones by land and sea through Venice, Lisbon, and the Netherlands. In the seventeenth century, as the presence of the British in India increased, the East India Company began to dominate the export of diamonds from India. Rough diamonds were routed through London and circulated from there to other cities, such as Amsterdam, Antwerp, and Paris, all of which were cutting centers that specialized in faceting gemstones into table, rose, brilliant, and other cuts. By adding more facets, lapidaries were able to unlock even more brilliance and "fire" (the rainbow of spectral hues) within the gemstone.

While today diamonds are a traditional part of engagement and other fine jewelry, we hope that this small display may reveal to visitors the long and complex journey of diamonds in the pre-modern period. From the center of the earth, where they were formed of pure carbon, to the alluvial deposits of the Indian subcontinent, the markets of London, and the cutting centers and jewelers of Europe, these remarkably hard and tenacious gemstones reveal the truth behind the brilliant De Beers advertising slogan, "a diamond is forever."