Jan van Eyck (Netherlandish, ca. 1390–1441) and Workshop Assistant. The Crucifixion; The Last Judgment, ca. 1440–41. Oil on canvas, transferred from wood, each: 22 1/4 x 7 2/3 in. (56.5 x 19.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Fletcher Fund, 1933 (33.92ab)

From Maryan Ainsworth, curator in the Department of European Paintings:

Having recognized through technical examinations that the fragmentary texts discovered on the frames of Jan van Eyck's Crucifixion and Last Judgment were original, or at least added at extremely early stages of the work, we then had to decide how to proceed. Thorough discussions needed to take place to identify all of the options available to us for the next stages—not only of the full recovery of the text, but also of its ultimate presentation to our viewing audience. This week, paintings conservator Sophie Scully discusses the options for revealing the original inscriptions and how best to restore and present these compromised frames in the galleries.

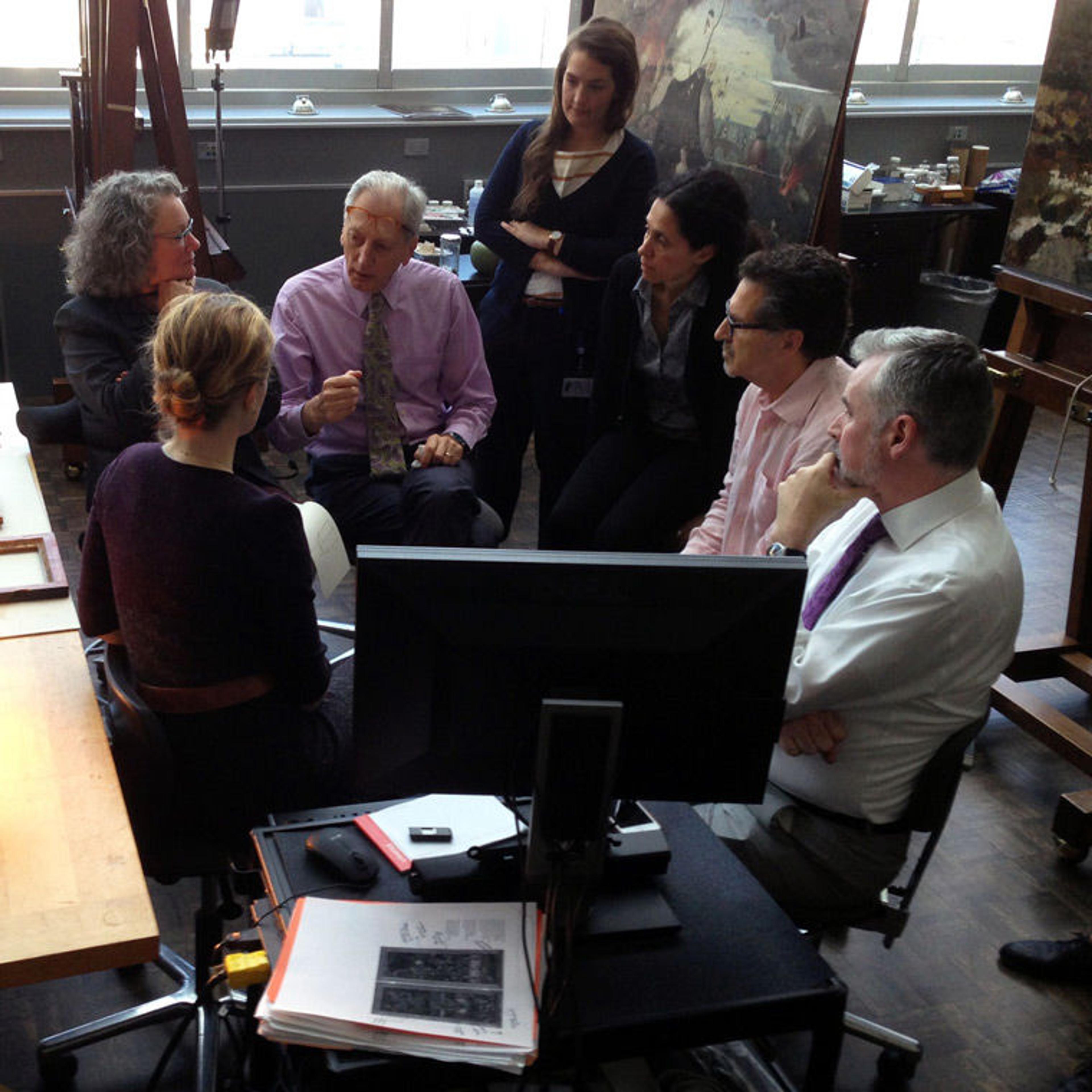

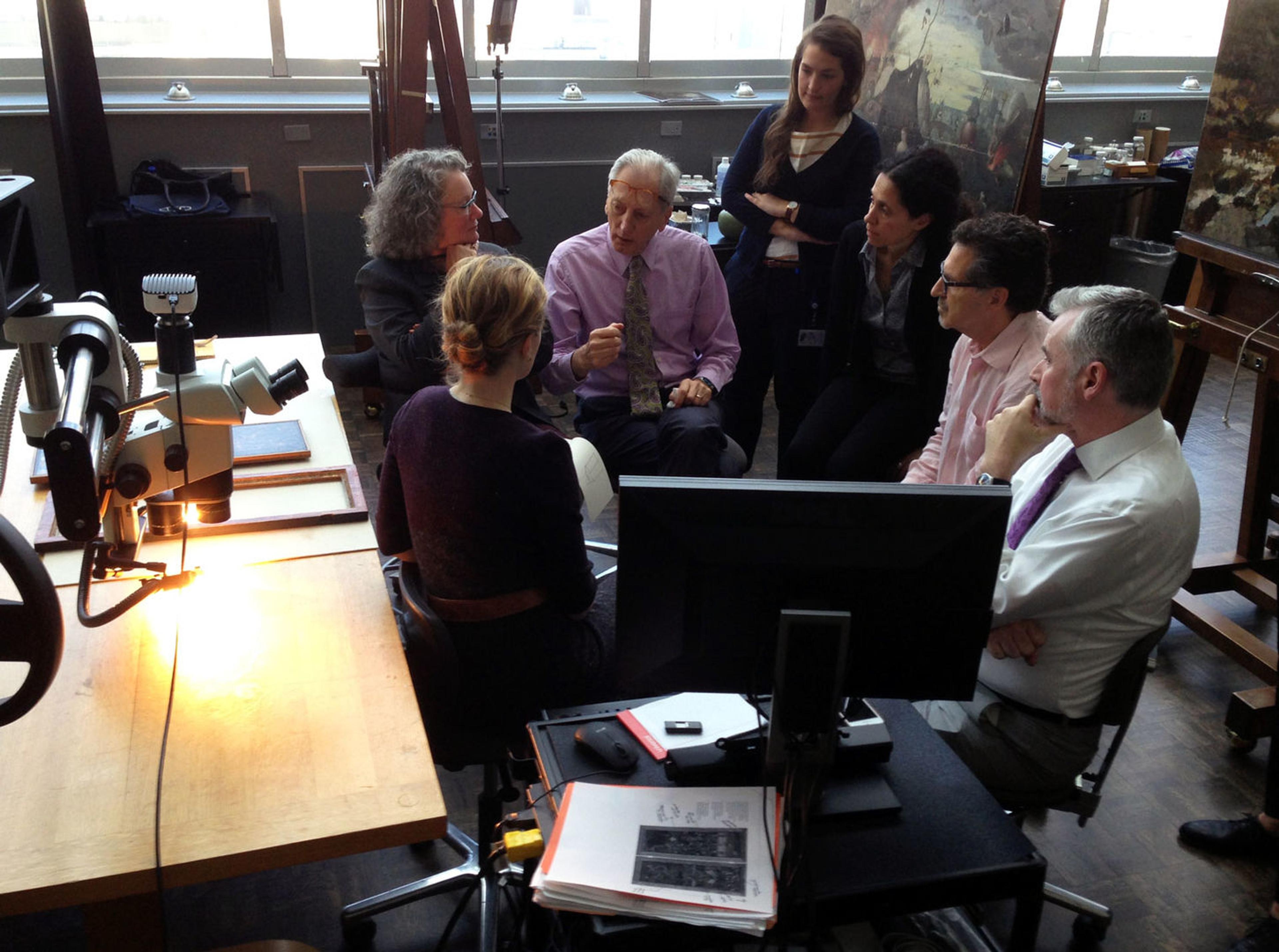

The discovery of original painted inscriptions on both frames led a group of Met curators, conservators, and scientists to consider removing the brass leaf and other later restorations in order to reveal the frames' original presentation. On the one hand, of course we wanted to see the original! But the decision to remove old restorations and repaint from a work of art is not so simple. What was the condition of the restoration and of the original? Would removing the restoration improve the appearance of the artwork? These questions were debated among many colleagues, and we arrived unanimously at the same decision.

Met staff discuss the treatment options available for the Van Eyck frames. Pictured here, from left to right: author Sophie Scully (facing away); curator Maryan Ainsworth; Keith Christiansen, John Pope-Hennessy Chairman of European Paintings; Linda Müller, former Slifka Foundation Interdisciplinary Fellow; research scientist Silvia A. Centeno; conservator George Bisacca; and Michael Gallagher, Sherman Fairchild Chairman of Paintings Conservation. Photo by Charlotte Hale

We knew that the original inscriptions were fragmentary and the decoration quite damaged, so we considered simply documenting our findings and leaving the frames as they had been. However, the overly bright brass leaf was not sympathetic to the paintings, and the irregular, lumpy surface was itself distracting. Even a highly damaged original would be preferable. Additionally, the opportunity to learn more about how these frames originally appeared was of immense value. So we made the decision to thoroughly document the previous restorations and remove them.

The author removes previous restorations from one of the frames. Photo by Keith Christiansen

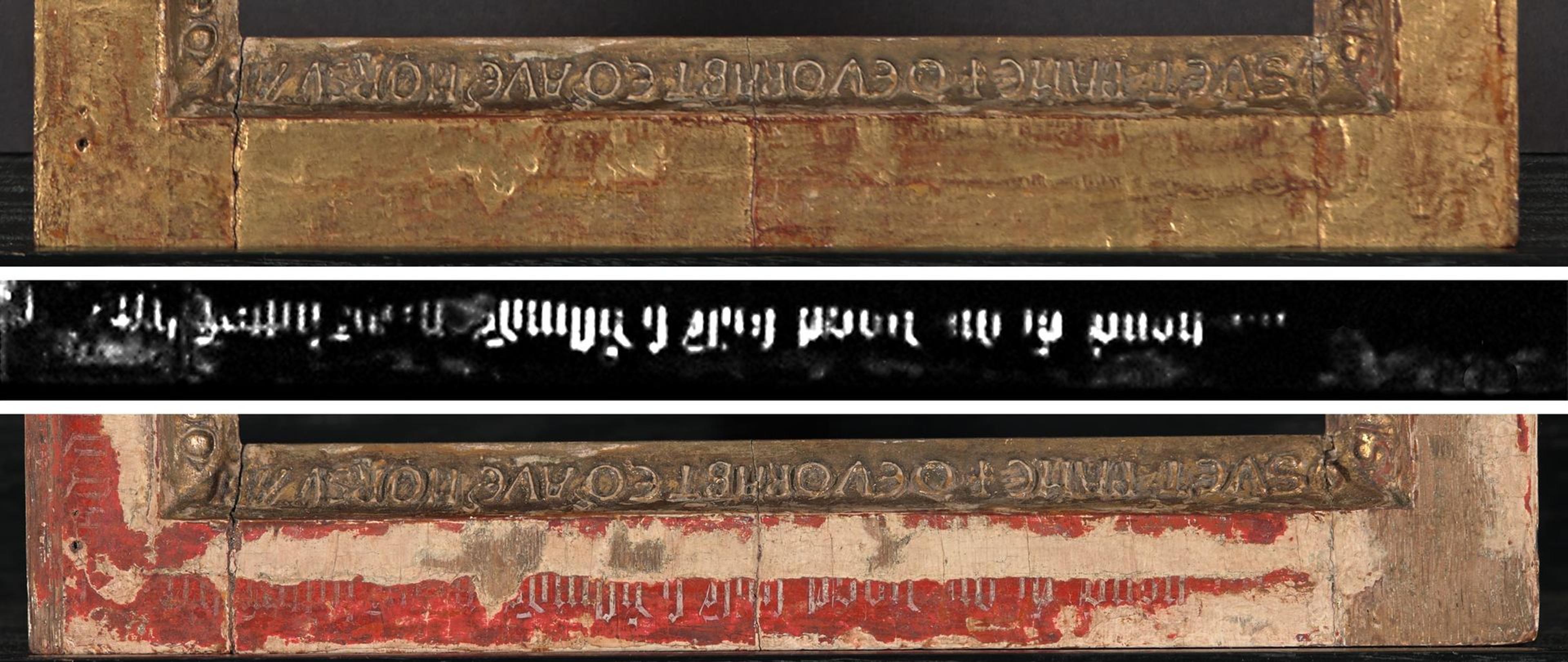

Carefully removing the many layers of restoration without harming the original was a painstaking process to say the least—one that I carried out using surgical tools under a microscope over the course of a few months. The first discovery I made upon removing the restorations was that the white and black inscriptions were painted in a highly delicate and calligraphic manner. These tiny fragments of paint, which appeared as blobs in the XRF maps, could now be deciphered as parts of letters.

Lower member of the Last Judgment frame shown: before treatment (top); in a lead distribution map acquired by XRF scanning (center); and after cleaning (bottom)

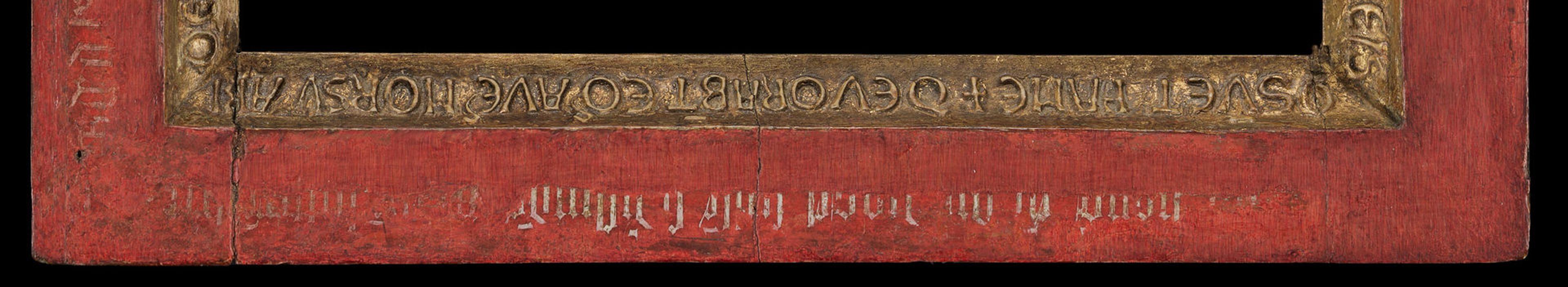

Even the pattern of damage on the red outer border was illuminating. It became clear that the original decoration had been deliberately scraped down to the bare wood, with the curving marks of a blade evident in a few spots.

The Crucifixion (left) and Last Judgment (right) frames after previous restorations were removed

This devastating damage most likely occurred when the paintings were reframed in an Italian-style tabernacle frame while housed in Naples in the seventeenth century. At that point the columns of the tabernacle would have been adhered to the vertical members of the frames with a pediment at its peak.

Line drawing of the tabernacle frame that likely held the Van Eyck paintings in the seventeenth century. Drawing by Dan Kershaw

The final question that remained was how to display the frames in the gallery. It became clear that we could not put the paintings back in their frames in this stripped state, as the damage distracted from these exquisitely executed paintings. They were also no longer fulfilling their basic function: to frame the paintings. So we decided to restore the red color but not the original inscription. Since we didn't entirely know what it was or how it was painted, a reconstruction would have required too much guesswork.

Hitting on just the right red was a challenge. Although originally painted a solid red, the upper layer had turned a darker, grayish red in places, most likely a result of the degradation of vermilion, the red pigment used. Where the paint had been scraped, bits of brighter red peeked through.

It wasn't a matter of simply inpainting the same red everywhere, as there wasn't a single consistent red to work with! I first added shallow white fills to the damaged areas, and then retouched with a bright red paint similar to the lightest red found in the original. Unfortunately, this was far too bright and projected forward optically, overwhelming the original, so I then gradually added some darker red with fine vertical brushstrokes, thinking of this darker color almost as a patina.

The Crucifixion (left) and Last Judgment (right) frames, after treatment

Detail of the lower member of the Last Judgment frame, after treatment

The goal was that viewers would have a sense of the original effect of old, worn red frames from a distance, but would be able to easily distinguish the original areas from the restored ones upon closer viewing. The true test was putting the frames back on the paintings. To our delight, everything came together harmoniously, and the new appearance of the frames set off and complemented the paintings. To judge for yourself, please visit the paintings in gallery 641!

The Crucifixion and Last Judgment reinstalled in their newly conserved frames in gallery 641

Now that the inscriptions were visible once again, we were curious to learn as much about these tiny fragments of letters as possible. Could the text be deciphered? And could reading the inscriptions tell us more about when and where the inscriptions were made? Could they date to Van Eyck himself or were they a later addition? Next week, paleographer Marc Smith writes about his investigation of the mysterious texts.

The Crucifixion and The Last Judgment are on view at The Met Fifth Avenue in gallery 641.

Related Content

Explore all of the articles in this blog series.

Read a selection of essays on the Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History that discuss topics related to this article: "Early Netherlandish Painting"; "Jan van Eyck (ca. 1390–1441)"; "Painting in Oil in the Low Countries and Its Spread to Southern Europe."

What's going on in The Met's Old Master galleries? View the web feature Met Masterpieces in a New Light to learn about the European Paintings Skylights Project, in which the skylights that admit natural overhead light into the galleries for optimal viewing of the collection will be replaced, in order to update and improve the quality of light in the galleries and resolve basic maintenance issues.