“Can you hear what we’ve learned throughout the years?” croons violinist, record producer, and 2024 MacArthur Fellow Johnny Gandelsman in composer Marika Hughes’s nouveau-folk song “With Love From J,” his singing voice hushed and gravelly. He channels the weary defiance of Pete Seeger with languid guitar strums, a far cry from his native instrument. “That love, sweet love, reminds us what to listen for…”

At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, in the wake of George Floyd’s murder and amid increasingly divisive rhetoric surrounding the 2020 election, Johnny Gandelsman commissioned twenty-five U.S.-born and -resident composers to respond to their current experiences in the fraught United States. The open-ended prompt gave way to an anthology entitled This Is America, which charted the wild range of emotions and sentiments during those complex times. Some composers, like Hughes, conveyed their fervent resistance against the status quo; others found unexpected joys in the uncertainty surrounding isolation.

Johnny Gandelsman in performance at The Met Cloisters, May 2023. Image © Stephanie Berger Photography, Inc.

Four years after the monumental project took its first steps, and following his sold-out marathon Bach series at The Met Cloisters, Gandelsman brings the full This Is America anthology to the American Wing’s galleries. The timing is doubly apropos: The violinist will help to herald the wing’s hundredth anniversary on November 8 and 9, just a few days after U.S. citizens cast votes for their forty-seventh president.

Gandelsman had just returned from a lengthy tour with his string quartet, Brooklyn Rider, when we chatted a few weeks ago. At home in New Paltz, New York, his Zoom background showed tokens of daily life: drawings from his children, a multiplication-tables cheat sheet. We discussed This Is America’s origins and how its themes echo in the current moment and beyond. Our conversation has been edited and condensed for publication.

Emery Kerekes:

Tell me about the genesis of This Is America. At what stage of 2020 did you decide that this project needed to exist?

Johnny Gandelsman:

New York City was closing down in mid-March 2020. My partner and I were living in Brooklyn at the time, and she was the one who said, “We have to get out of here.” So we packed up our car and took our kids to New Hampshire. At the time, nobody knew what was happening or how long it would last. We thought we were going for a couple of weeks, and we ended up staying for six months. We were living in this beautiful, safe place. There was snow on the ground. My kids didn't have to wear a mask for months, because there was nobody around. But it was really strange to be there, scared, away from our friends and our families.

In the very beginning, everybody was mounting online performances. There was a Facebook or Instagram Live event almost every day. As performers, our natural first response is to perform music for those who need it. But at the same time, all of our live performances were getting canceled, one by one.

Then George Floyd happened, and the election cycle started to ramp up. At that point, I was just trying to figure out how not to feel totally hopeless. It’s one thing if you can gather with friends—but what can we do when we’re totally isolated and removed? So I had this thought of asking composers to write new works, just reflecting on what’s happening. I didn’t know it was going to be an anthology.

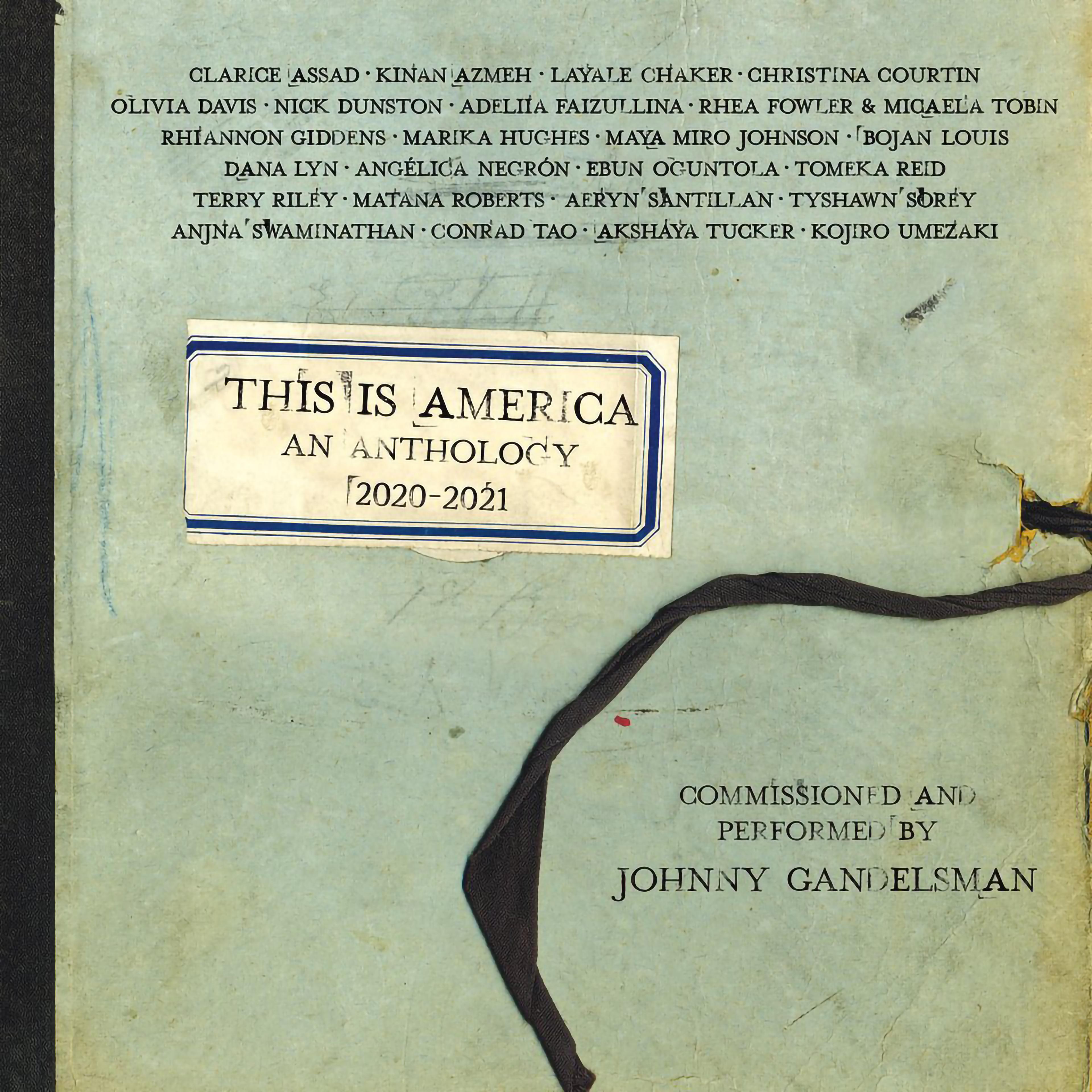

Cover art for This is America. Image courtesy of In a Circle Records

Kerekes:

That’s a pretty open prompt—just react.

Gandelsman:

Yeah, it was, and I think the prompt resonated with composers and with presenters. I asked the Hopkins Center at Dartmouth first, and once they were on board, the project started to grow. In the end, twenty or so presenters all around the country were involved.

There was plenty of interest from big presenters, but I was touched that there were also a lot of small companies who hopped aboard, even though they were struggling. When they expressed interest, that's when I thought that there's meaning and importance to this—not just for me and for composers, but for our community at large.

Kerekes:

I feel like that’s a crisis a lot of artists encountered during the pandemic: As the world crumbles around us, how do we make our art matter? What importance does it have?

Gandelsman:

And that’s constantly on my mind—what should the artist’s role be? My dear friend composer and clarinetist Kinan Azmeh always says: Objectively, music can’t stop a bullet. But it can open someone’s mind or heart, or make someone consider a different point of view, or learn something, or overcome a fear of the unknown. I’ve spent my life playing the music of Mozart and Bach—elevating their voice. And likewise, I feel it’s just as important to elevate the voices of people who are alive today.

I’ve spent my life playing the music of Mozart and Bach—elevating their voice. And likewise, I feel it’s just as important to elevate the voices of people who are alive today.

Kerekes:

One of the amazing things about this project is that it draws on so many lived experiences. As the performer, how do you take such diverse points of view and interpret them through your own perspective?

Gandelsman:

I don’t know that it’s so different from how one would approach Beethoven, except that there’s an opportunity to connect with the composer directly—a path to overcome any discomfort or unfamiliarity. They guide you through their thought process and what they’re looking for.

When I was working with Silkroad Ensemble, that was a big takeaway. How to deal with that constant interaction with the unfamiliar, and how to find your way out of the fear of the unknown and into something that’s honest and respectful, where you can feel like a full participant. Those experiences inform any time I commission new music.

Kerekes:

What were some of the new skills you had to learn for this project? For instance, do you sing? Or play guitar?

Gandelsman:

[shaking head vigorously] Nope. I mean, I don’t think Marika Hughes intended for me to play guitar. I think she thought I’d just play it on violin. But when she sent her sample recording, it was just so beautiful. I couldn’t imitate the guitar’s resonance and immediacy. A dear friend helped me out, but my guitar playing certainly isn’t good—and I’m not a singer either, as my kids will attest. But I wanted to try as best I could.

There were a few pieces that were improvisatory in nature. I wouldn’t call myself an improviser, and that freaked me out at first. I had no idea how to interpret them, and my first reaction was panic and rejection, putting a value judgment on the piece itself, just because I was terrified.

But the composers were kind and thoughtful guides into their worlds. It’s partially that all the composers I commissioned are also performers, and there’s a performer-to-performer empathy which helps with that process. It’s this ethos of, “Here, let me show you—but make it feel right for yourself.”

Kerekes:

Tell me a bit about the collaboration process for this project. Some of the composers you commissioned were old friends, and some were newer connections. What's it like to forge those new connections when you can’t be in the same space?

Gandelsman:

People work in very different ways. Some composers were very collaborative, and some didn’t need to be. Like, Tyshawn Sorey just delivered me a finished piece! And there’s no right or wrong, they’re equally valid—but it was cool to interact with both ends of the spectrum, and I learned a lot about myself and how to approach new, unfamiliar things going forward. And how to manage expectations.

So, for example, I’d never met composer Terry Riley, who moved to Japan at the beginning of the pandemic, but I’ve worked plenty with his son Gyan—that’s how we first established contact. Terry and I had some Zoom meetings to talk through ideas. Then he’d send me a sketch, I’d record it with my phone, send him the voice memo, and he’d approve or tweak. His note for the piece, “Barbary Coast 1955,” is hilarious—and also, shows exactly how the piece came to be!

And I’m still just now meeting the people I commissioned for the first time in person. The youngest composer on This Is America, Èbùn Oguntola, was in high school at the time of commission, just sixteen years old. Èbùn and I waved at each other during the “premiere” of her piece, which was videotaped in an empty concert hall, but we finally met when she joined my recent residency in Worcester, Massachusetts. You forget how isolated everything was until you’re sitting in a room talking without a mask.

Kerekes:

You’re bringing this to the American Wing’s one-hundredth anniversary on an incredibly auspicious weekend. What do you think it means to be presenting this performance in the American Wing, which displays so many facets of this country’s history?

Gandelsman:

The idea came up in conversation with [Lulu C. and Anthony W. Wang General Manager of Live Arts] Limor Tomer. We didn’t originally plan to present the entire anthology, but Limor and I can both be maximalists, and it made sense because of the occasion.

Music is part of the American experience. All of the composers I commissioned are American or work primarily in the U.S. This was their response, in their own very unique ways, to the experiences of living here during that time. So it makes perfect sense to be in the American Wing of The Met.

View of The Charles Engelhard Court (Gallery 700) in the American Wing. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. May 2011

I also like that this is a museum with fixed, unmoving art. I get to animate those stationary works in a visceral way. I won’t know how that feels until I’m in the moment, doing it.

Kerekes:

You’re presenting this performance for free with museum admission, which means the audience will cycle in and out, happening on the performances organically. What sort of impact do you hope to have on those spectators for whom this is a small part of their Museum experience?

Gandelsman:

I hope they will find something interesting or memorable, that will make them want to stay for the whole performance, or at least wonder why it’s there. I’m hoping that for some people, regardless of what happens on election Tuesday, hearing live music in community with other listeners will feel good.

Kerekes:

How does this project reflect what you’re feeling at this moment?

Gandelsman:

When George Floyd was killed, people would put black squares on their social media accounts. The conversation was front and center in our community, and people were vocal with their frustrations as organizations made statements for the sake of public image without any meaningful change. It was a very intense time, and I don’t actually know what we’ve gotten out of it.

That’s why it’s been interesting to come back to these pieces. I premiered and recorded them over 2021 and 2022, and returning to them this season, I realize that things haven’t changed all that much. Part of it is that we’re back in an election cycle, and it’s just as horrible, if not worse than it was in 2020. And add to that the wars and the natural disasters.

I feel like there’s even more need for hearing and lifting up other people’s voices. The conversations are still so binary—if you’re for this, you’re against this. It’s so easy to sit in your safe home and comment on other peoples’ lives thousands of miles away, but it’s also easy to forget that people are actually living those lives.

Honestly, it’s hard to feel very positive about things right now, but I do get a lot of joy out of participating in this kind of work. There are so many wonderful musicians and composers, and that’s where one can find reasons to keep doing what they’re doing. Music has a way of communicating things that are really hard to say. I feel that through sound…well, I don’t know if it provides an answer or more questions, but it can at least move the brain or heart a little bit.

Kerekes:

It gets back to that question of “Does this matter?” We can talk about music’s impact on the greater world all we want—but the impact on the individual is as important, if not more so.

Gandelsman:

Music has a way of introducing people to the unknown. If we’re all in our silos of safety and reject everything that we don’t know, nothing good comes of it. This Is America provides an opportunity to face things that can be challenging, but there’s a lot of reward in that.

I don’t expect everybody to like everything. In fact, I expect people to be surprised or uncomfortable with some of the material. But I would say, in this small way, what musicians do can make a little difference. And if I ever get to a point where I feel like it can’t, then I probably won’t play another note—there would be no point.