Firelei Báez explains how her painting is an ode to Lauren Olamina, the protagonist of Octavia Butler’s Earthseed series.

Set in a dystopian near-future United States, the novels imagine a world on the brink of political and environmental collapse. Against this backdrop, Olamina establishes a new religion to envision a future liberated from the unrelenting demands of industrialization—one that centers moments of rest and reflection.

Museums Without Men: Firelei Báez

Listen to the conversation, or read the full transcript below.

Transcript

FIRELEI BÁEZ: I’m Firelei Báez. An artist, painter, sculptor, you name it.

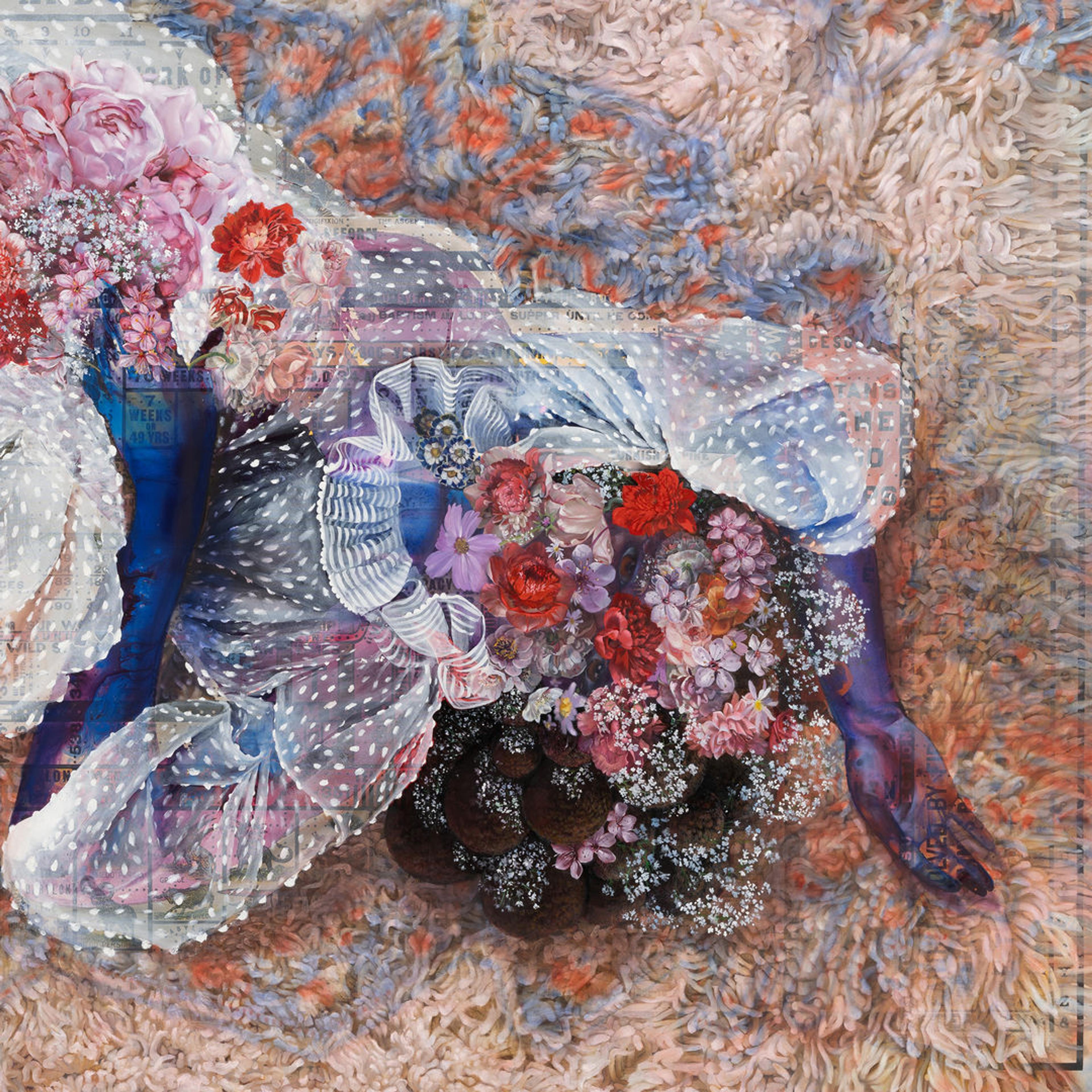

KATY HESSEL: Báez is standing in The Met’s Modern and Contemporary Wing in front of her painting. Its surface is dense with lavish textures and colors, and if you look closely, beneath it all, there lies a woman.

Firelei Báez (Dominican, b. 1981). Olamina (How do we learn to love each other while we are embattled), 2022. Oil and acrylic on inkjet on canvas, 86 1/2 in. x 9 ft. 6 1/2 in. x 1 1/2 in. (219.7 x 290.8 x 3.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Purchase, Civic Practice Partnership Artist Residency, Anonymous, and Lila Acheson Wallace Gifts, 2023 (2023.355). © Firelei Báez

BÁEZ: So this person having a moment of rest on this very soft rug, enveloped by all these fragrant, beautiful flowers.

The title of the piece is Olamina (How do we learn to love each other while we are embattled?)—and that is meant to have many different reads to it. First being that it is an ode to Lauren Olamina, the protagonist of the Earthseed series from Octavia Butler. And in those novels, the world is eerily similar to many of the things we were going through in the world, specifically in the United States—political chaos, environmental distress, policing the body, especially the female body.

HESSEL: The main character of the series, Lauren, is a young Black woman who establishes a new religion and envisions a better future while navigating a present moment teeming with corporate greed and violent politicians.

BÁEZ: And when you’re reading through the story, if you read through it very quickly, you’re like, “Oh my goodness. This is a world in collapse.” And then you read through again and you realize at every point of crisis, she centers a moment of rest.

Before any major battle, she says we cannot address it until we are whole. If we don’t rest at this point, we can win the battle, but we won’t win the war. I kind of get all—sorry—worked up about it, but it’s just incredible that she would have the vision to show both the truth of the crises, and ways out of it.

This idea of having to fix the system—to teach how to change racism, to teach how to end industrialization—the onus of fixing it and teaching is on specific bodies, specific communities.

I wanted to acknowledge that history. And still give a moment of rest, like collectively, we cannot face all that until we are whole. And so that’s why she’s in this moment of repose.

HESSEL: Rest, or rather a lack of rest, is something Báez contends with in her own life and painting practice as well

BÁEZ: Coming into the art world without any financial support meant that I had to, for this thing I love and that makes me feel alive, I had to sacrifice being close to my family. I many times had to have five jobs at once. So creature comforts became secondary, and they shouldn’t have. As a young woman, to then have the space to again rest or bring rest to other people has been almost impossible.

Even when there were extraordinary women painting historically, the fact that their works were either subsumed or had to be extremely exceptional to ever be noted was something I was aware of.

And so, what was I adding to that canon? How was I opening it? How was I making room for others?

Because as much as we think of our ancestors, how do we become better ancestors for other people moving forward?

HESSEL: Listen on to hear more incredible stories about great women artists at The Met.

###

This audio tour is one in a series of tours called Museums Without Men produced by Katy Hessel in collaboration with institutions across the globe, such as the Fine Arts Museum San Francisco, the Hepworth Wakefield, the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, and Tate Britain. The series encourages museum visitors to seek out work by great women and gender non-conforming artists in these institutions who, simply by virtue of their gender, were often overlooked and underrepresented.