This GIF shows the before and after of a digital reconstruction: Margareta Haverman (Dutch, 1693–1722 or later). A Vase of Flowers (detail), 1716. Oil on walnut panel, 31 1/4 x 23 3/4 in. (79.4 x 60.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, 1871 (71.6)

In the course of conserving Margareta Haverman's stunning still life A Vase of Flowers, we found that an organic pigment—specifically, a yellow lake pigment—had faded in the centuries since the painting was made. (You can read more about the results of our conservation treatment and technical study of the painting in "Honoring a Legacy: The Conservation of Margareta Haverman's A Vase of Flowers.") This finding led us to make a digital reconstruction of the painting to better see how it would have appeared in 1716 when Haverman completed it.

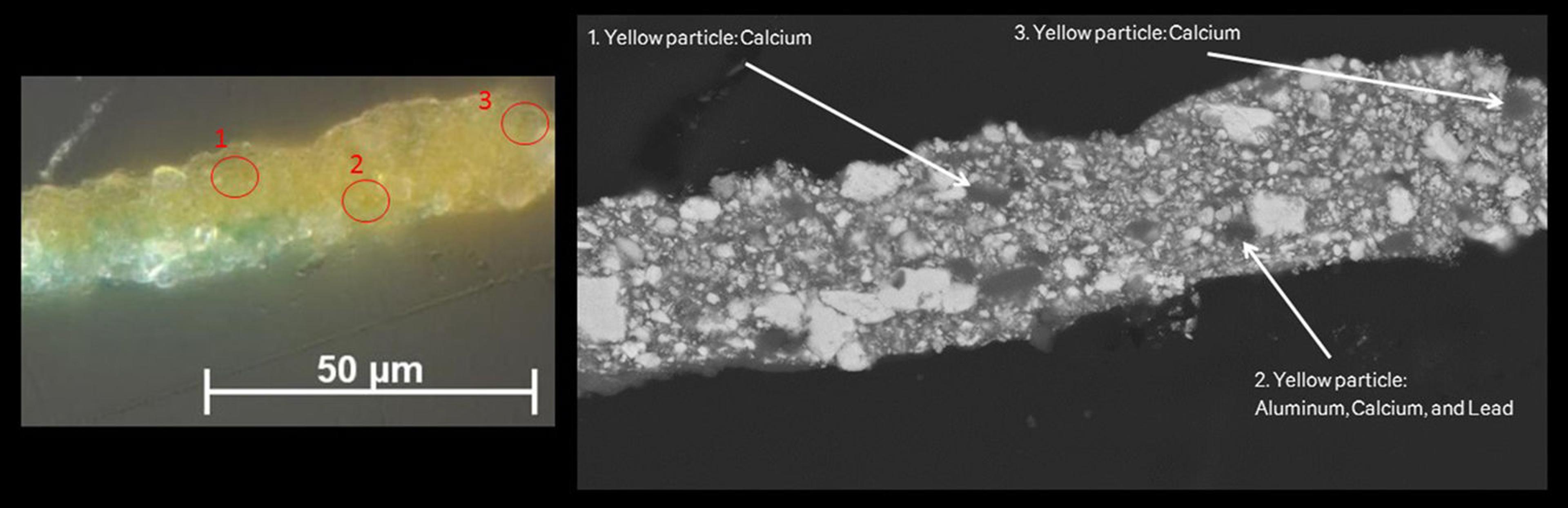

Digital reconstructions of paintings are complex undertakings, and this one required help from members of multiple departments in the Museum. To make our digital reconstruction, we first analyzed a sample of unfaded yellow lake pigment that had been protected from light by overlying paint layers. In the early eighteenth century, yellow lake pigments were made by combining yellow organic dyes, extracted from plants such as weld or from buckthorn berries, with an inorganic base, like alumina (aluminum oxide) or chalk (calcium carbonate). This converts the liquid dye to an insoluble powder that can be ground into oil and used as paint. When we looked at the sample with a scanning electron microscope (a device that can detect the elements found in individual pigment particles), we discovered that, for the most part, Haverman's yellow lake contains a calcium base.

Left: A few unfaded particles of yellow lake are visible in the paint sample, observed under the microscope at 400x magnification. Right: Analysis with a scanning electron microscope (SEM-BSE and EDS) shows that most of the yellow lake particles contain a calcium base.

This finding was important because it could help us identify where else on the painting that pigment appears. We then scanned the painting using our x-ray fluorescence (XRF) scanner, which records the locations of different elements across the surface of the painting, and we used the resulting calcium map as a guide for where Haverman applied the now-faded yellow lake. However, because calcium is also found in other pigments, we had to make some edits to this map. For example, Haverman also used the calcium-containing pigment bone black in A Vase of Flowers. So, using a microscope to inspect the surface of the painting, we edited the calcium map to exclude areas that clearly contained bone black.

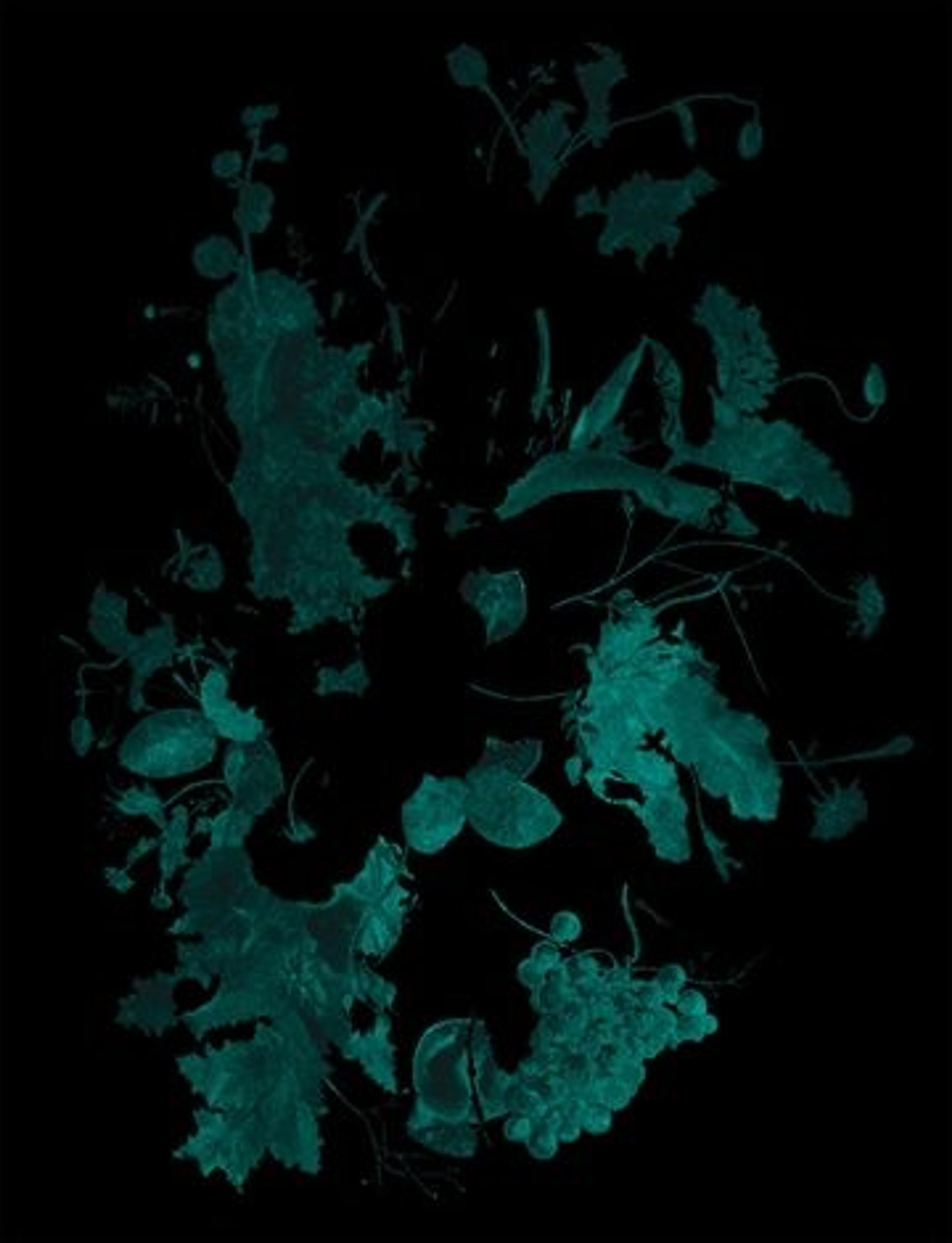

Left: This XRF scan showing the distribution of calcium in the painting was used to locate the presence of yellow lake pigment, and was edited in Photoshop to eliminate areas that corresponded to other calcium-containing pigments, such as bone black.

At this point, we had determined the locations of faded yellow pigment, but we still needed to know the original shade of the yellow lake as it appeared in 1716. Using the same paint sample that we examined under the microscope, we obtained a precise color value by using state-of-the-art color-measurement software. We also took color measurements of the painting itself, using a spectrophotometer to double-check the color accuracy of our digital photograph, ensuring that the image we were starting with would be as close to the painting's true color as possible.

Now armed with a roadmap of the faded pigment and a precise color value of the unfaded pigment, our final task was to use Photoshop on the digital image of the painting to reintroduce the yellow hue where it had faded. After our rigorous technical study, you might think this process would be straightforward, but this was not the case! In our first draft, the painting looked flat and the yellows appeared sickly. Certainly, the leaves and stems of the flowers looked much greener than before (they'd turned blue as the yellow faded over time), but we could not believe that Haverman, whose tremendous abilities as a flower painter are evident in this painting, would have been happy with this outcome.

Right: This detail shows the copper-based glazes on the large opium poppy leaf at the bottom left. There is no consensus among scholars on exactly what these glazes are intended to represent.

To make sure the image didn't appear flat, we adjusted the way Photoshop integrated the yellow into the composition, ensuring it wouldn't interfere with Haverman's dynamic shadows and highlights. We increased the intensity of the yellow in certain areas, such as the hollyhocks, and lessened its effect in others, such as the green grapes. Eventually we thought we had the yellows just right. But then, the red roses appeared too pale in comparison, and parts of the copper-based glazes on some leaves appeared somewhat brown. To address these issues, we took a color measurement of the red lake, another organic pigment that can fade just as readily as yellow lakes, and adjusted the hue of the roses. For the copper-based glaze (which is notorious for discoloring to brown over time), we dialed back the warmth of the most discolored-looking brown spots, restoring them closer to their original hue.

These glazes continue to pose some questions for scholars, as there is no consensus either inside or outside of the Museum regarding what they are supposed to depict. Could the brown tones represent decay, as leaves begin to wilt and die? Or could they represent a lighting effect—a warm glow either shining through or reflecting off that area of the leaf? Without a definitive answer, we made only minimal interventions in these areas.

In the end, after much research and deliberation, we arrived at this:

Use the slider to compare and contrast a photograph (left) and digital reconstruction (right) of Haverman's still life.

You might understandably wonder if the small adjustments we made are too subjective for a project that has its roots in objective, scientific measurements. We, too, grappled with this feeling at each stage of the editing process. But it is important to point out that although the equipment we use is sophisticated, it cannot provide answers to every question. Moreover, trying to force a beautifully observed and carefully painted work of art to align with objective data points will always leave something to be desired. Just as poetry cannot be reduced to the individual words on the page, a painting is far more than the sum of its individual pigment particles.

The results of our work certainly do much to improve our understanding of the painting's original appearance. For instance, we can see that the added yellow and red provide a degree of warmth to the painting, which nicely counters the cool blues in the hyacinths and passionflower. Digitally restoring the yellow in the foliage also allows it to recede in the shaded areas, enhancing the three-dimensionality of the bouquet and positioning it in space even better than before. In the end, this digital reconstruction, based on the results of our technical study, was an iterative process that brings us closer to understanding how Haverman's painting might have originally appeared just over three hundred years ago.

Thanks to everyone who helped, or gave advice, including: Adam Eaker, Charlotte Hale, Michael Gallagher, Dorothy Mahon, Silvia Centeno, Federico Carò, Chris Heins, Scott Geffert, Evan Read, Nouchka de Keyser, Paul Taylor, Arie Wallert, Marika Spring, Jo Kirby-Atkinson, and Tessa Huxley.

Related Content

Margareta Haverman's A Vase of Flowers is included in the exhibition In Praise of Painting: Dutch Masterpieces at The Met.

Read more about the exhibition in an article by curator Adam Eaker, "In Praise of Painting: Rethinking Art of the Dutch Golden Age at The Met."

Read more about the Haverman conservation in the article "Honoring a Legacy: The Conservation of Margareta Haverman's A Vase of Flowers."