From Don Undeen, Senior Manager of Media Lab:

In writing about art history and museum studies, we sometimes talk about the "aura" of an art object—the idea that a work of art carries with it its history, meaning, and authenticity. To further abuse Walter Benjamin's ideas, as expressed in his essay "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction," sometimes I even imagine that aura as an invisible cloud of data floating around the object. Augmented reality (AR) is a technology that gives us a sort of magic window through which we can view our everyday world overlaid with a fictive reality of our own creation. If AR could enable us to see an artwork's aura, what would it look like? Additionally, can we use AR to project our own auras onto an artwork? The Metaverses team at Brooklyn College's PIMA MFA program joined with the Westbeth Home to the Arts, in conversation with Met curators, to develop an AR experience in the Met galleries that was deeply personal, highly interactive, and informed by the history and authenticity of the objects themselves.

«We are four interdisciplinary artists pursuing Master of Fine Arts degrees at PIMA, Brooklyn College. From January through May 2014, we were in residence at the Met's Media Lab, working in collaboration with five artists over the age of sixty who live and work at the Westbeth Home to the Arts in New York City's West Village. Together we created "Metaverses"—an augmented-reality tour of some of the Museum's collection.»

Origins

Our project began through Justine's friendship with Erica, a longtime resident of the Westbeth, one of the oldest artist residencies in the United States.

The residency was hit hard by Hurricane Sandy in 2012 and the building was without regular power, heat, and water for two weeks. Erica spent much of her time shuttling up and down many flights of stairs to bring water, blankets, and supplies to the older residents. She met many of her neighbors for the first time—amazing artists with colorful stories and full careers—and saw that many had lost much of their life's work due to extensive flooding in the basement.

When the four of us at PIMA began a course asking us to identify a community in New York City with which to devise and execute a socially engaged art project, Erica proposed to Justine that we work with the older artists at the Westbeth. Justine was excited, as she had long been interested in artist communities and the question of how artists sustain their practice and quality of life, particularly in a city as challenging as New York.

Unrelated to this development, Jason and Justine met Don Undeen, senior manager of the Met's Media Lab, at a Volumetric Society presentation and learned about the Media Lab's interest in hosting artists and technologists. After meeting with Don to discuss our work both at PIMA and as professional artists, we wondered if we could we could combine the two projects. Thanks to Don, we were invited to find out.

Left: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photograph courtesy Justine Williams. Right: The Westbeth Home to the Arts. Photograph courtesy Vanessa Gilbert

What would it mean to create a media-based, technology-driven arts project with older adult artists? There is poetry in a group of emerging artists and technologists working within an antiquities collection and with older adults, but how could technology be used as a tool for collaboration and as a means of exploring new facets of the Met's objects? The Met's mission is to present the broadest spectrum and highest level of human achievement. What would it mean, then, to transpose elements of Westbeth to the Met, and vice versa? Could we create a meaningful experience for visitors that activated the Museum and told the story of this encounter?

Excited (and daunted) by these questions, we joined forces to explore "The Art of the Encounter": using technology to connect individuals to one another and to the objects and spaces in the Met in surprising and meaningful ways. Using Aurasma (a free application for creating augmented-reality experiences) as our central tech tool, we devised an artists' hack of the Met.

The Process

We began with group visits to the Westbeth artists' studios and homes, discussing and archiving their histories as working artists in the Westbeth and New York City communities. Our collaborators were Christina Maile, a printmaker; Stephen Hall, a painter; Nancy Gabor, a theatre director; Paul Binnerts, a playwright; and Penny Jones, a puppeteer.

The four of us from PIMA each paired with a Westbeth artist and continued a more personal dialogue about art, life, and New York City. We visited the Met with our partners and shared objects that moved us. We then chose the objects that sparked an idea for either a visual or audio response.

Left: artist Vanessa Gilbert (left), with Westbeth residents Paul Binnerts (background) and Nancy Gabor (right). Photograph courtesy Jason Schuler. Right: Westbeth resident Christina Maile (left) and artist Justine Williams together in the studio. Photograph courtesy Vanessa Gilbert

We also met with Met curators from the Arms and Armor, Medieval Art and The Cloisters, and Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas departments. We were uniformly met with interest and curiosity, along with a genuine desire to assist us in getting Museum patrons to look more closely at the objects in the collection. The curators made themselves very accessible and we learned some wonderful secrets about the Museum (but that's another post altogether).

In total, we chose sixteen objects and spaces and began to imagine and create a range of interactive, media-based art pieces that responded in dynamic ways. Some of the pieces provide the viewer with a deeper sense of the object's cultural significance and time of origin. In other cases, the object was a springboard for creating a contemporary response. Some pieces were "meeting points" where an artist's voice or work combined with an object or space, creating a third object or space—a hybrid metaverse. And finally, some objects were used to facilitate interactions between tour participants, activating their experience of one another.

We were interested in the alchemy between viewer and object and between the two people, an idea drawn from language in the Met's mission, which refers to "kindred subjects" ("advancing the general knowledge of kindred subjects"). What happens when a viewer meets an object from another time and place, or when two people from different times and places come together?

To create our tour, we projected the Met's current map onto a wall, marked our chosen stations, and did a virtual dry run.

After a few weeks we met to prepare a map and to determine an order for our tour. We concluded that one of the most special parts of our project was the fact that we visited the Museum in pairs, and we wanted our audience to experience the same kind of exchange. Therefore, we decided we would pair our visitors in an intergenerational way.

To create these intergenerational pairs, we enlisted the collaboration of Older Adult Technology Services (OATS), a nonprofit organization that empowers seniors through access to technology. They run a technology "clubhouse" called Senior Planet, where we led a workshop called Creativity on the iPad. This enabled us to talk to seniors about our project at the Met and to allow them to feel comfortable with Aurasma.

The Tour

On May 16, 2014, we beta tested our tour on one of the rainiest days of the year. Our invited guests included Media Lab staff, Met curators, fellow students from Brooklyn College, members of OATS, and select friends and family, including the participating artists from the Westbeth. (Roughly forty people participated over four hours.)

When everyone arrived, we paired up our participants, with an ideal pair being strangers with a significant age difference. We then gave them everything they needed: an iPad to read the augmented-reality content; a headphone splitter; two pairs of headphones; and a specially designed tour map into which Patrícia ingeniously incorporated the visual artwork of both Christina Maile and Stephen Hall. (Thanks to OATS for the generous loan of iPads, and Brooklyn College for supporting us.)

Participants on the tour. Photographs courtesy Justine Williams

When they were ready, participants clicked on an introductory sound file that taught them how to use the Aurasma software. With that simple introduction, we sent the intrepid pairs off to the first stops in the Greek and Roman galleries and looked forward to their eventual return.

The stations on the tour each incorporated an interactive element, not all of which were based in augmented reality. One stop, the Cubiculum (bedroom) from the Villa of P. Fannius Synistor at Boscoreale, requested that the participants play an audio file of puppeteer Penny Jones describing her Westbeth apartment. This created a dissonant experience with the view of one space and the sound of another.

We could describe each stop of the tour, but we hope that you're now inspired to take the tour yourself.

Ludonarrative

Ludonarrative, something of great interest to the four of us, is a compound of ludology (game play) and narrative (story), and refers to when a player of a video game is able to control the story, rather than playing a fixed narrative.

In constructing Metaverses, there were two major considerations with regard to ludonarratives: bringing visitors closer to an object with technology, and the nature of the interactivity itself. It was important to us to create a sense of interactivity throughout the tour. Artifacts in the Museum are immobile, untouchable, and often separated from the visitor by glass, giving a sense of stasis. This can make Museums objects' stories feel fixed, at least historically, to visitors. Generally, though, their histories lend a far deeper significance.

The alchemy of game play and narrative that we created may be best represented by the tour's interaction with Oricale figure (Kafigeledjo), a figure that lives in the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas collection. The oracle, "he who speaks the truth," was at one time a tool for divination between the elders of the Senufo peoples and the general community.

Oracle figure (Kafigeledjo), 19th–mid-20th century. Côte d'Ivoire. Wood, iron, bone, porcupine quills, feathers, commercially woven fiber, organic material; H. 32 7/16 (82.5 cm) x W. 13 (33 cm) x D. 4 1/2 in (11.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Raymond Wielgus, 1964 (1978.412.488)

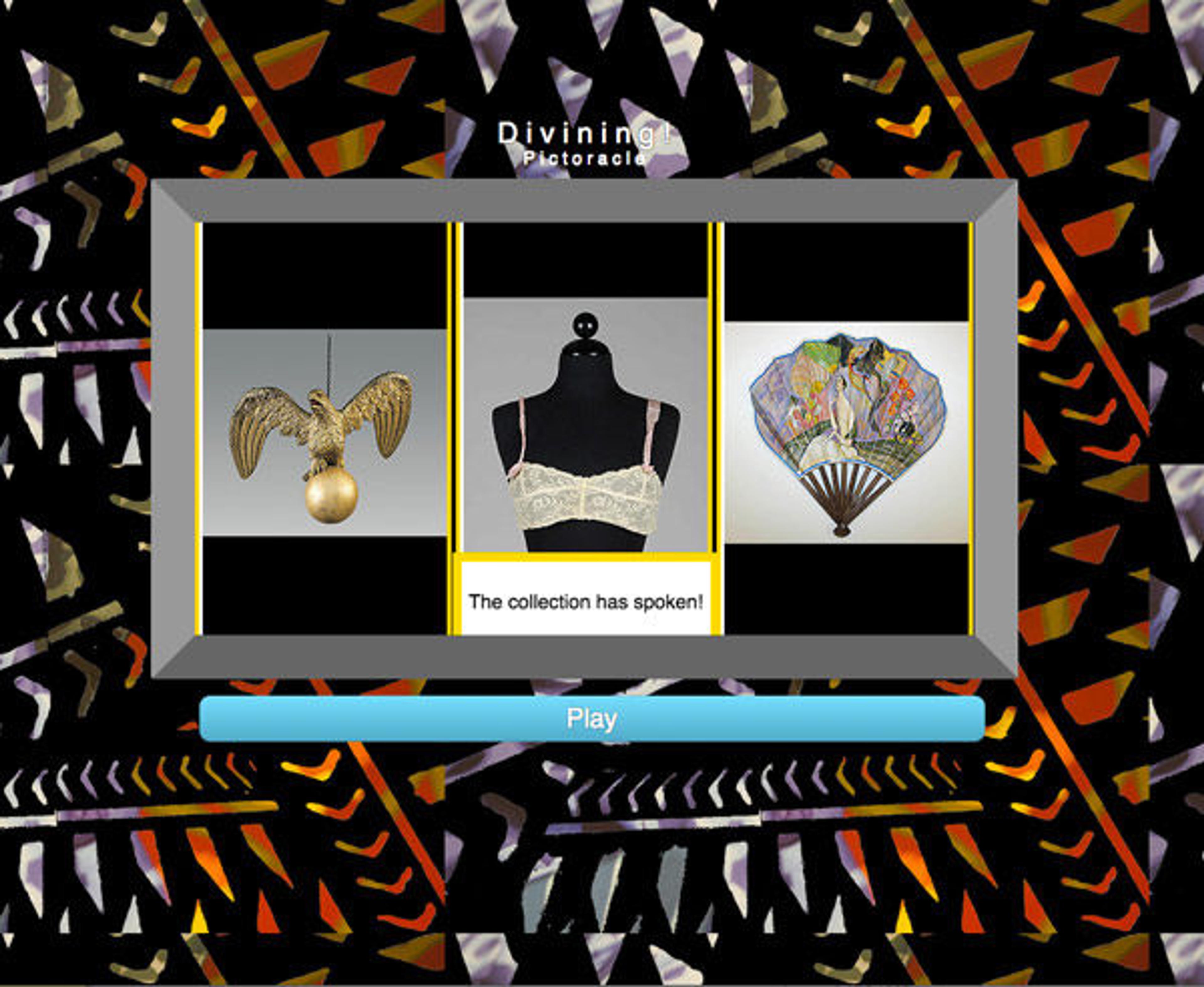

Justine, inspired by the figure and visits to the Museum with Christina Maile, created a modern-day "PictOracle"—an interactive divining interface that randomly chooses three images from a selection of the Met's collection of thirty thousand displayed artifacts.

The screen interface of the PictOracle. The collection has spoken!

The images are displayed like a casino slot machine for the elder member to interpret, and like tarot cards for the younger member who has asked an undisclosed, but significant question. The ludonarrative builds on the combined meaning of objects and facilitates the development of personal connections to objects that visitors might then choose to seek out on their journey.

Building Content with Aurasma

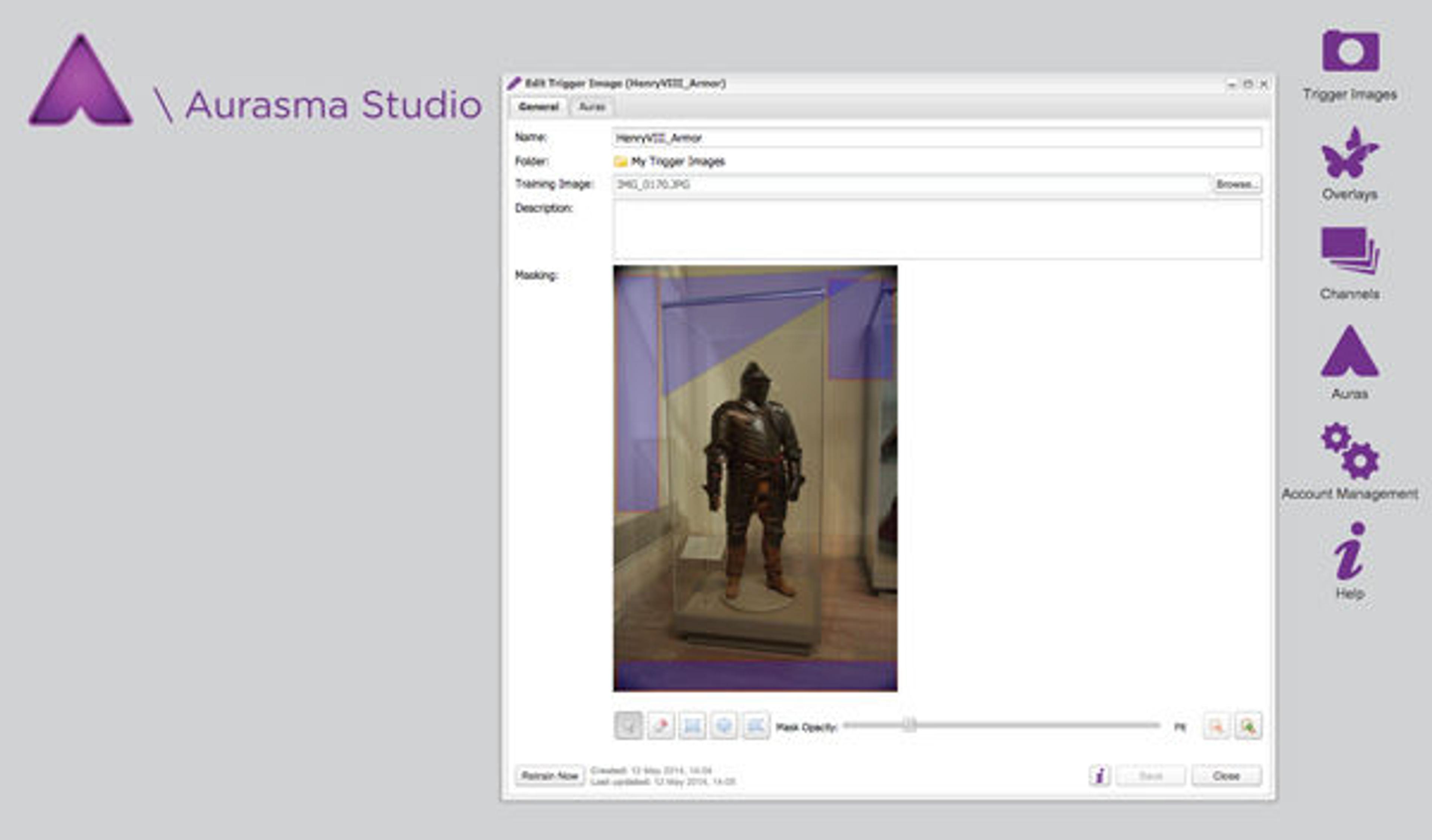

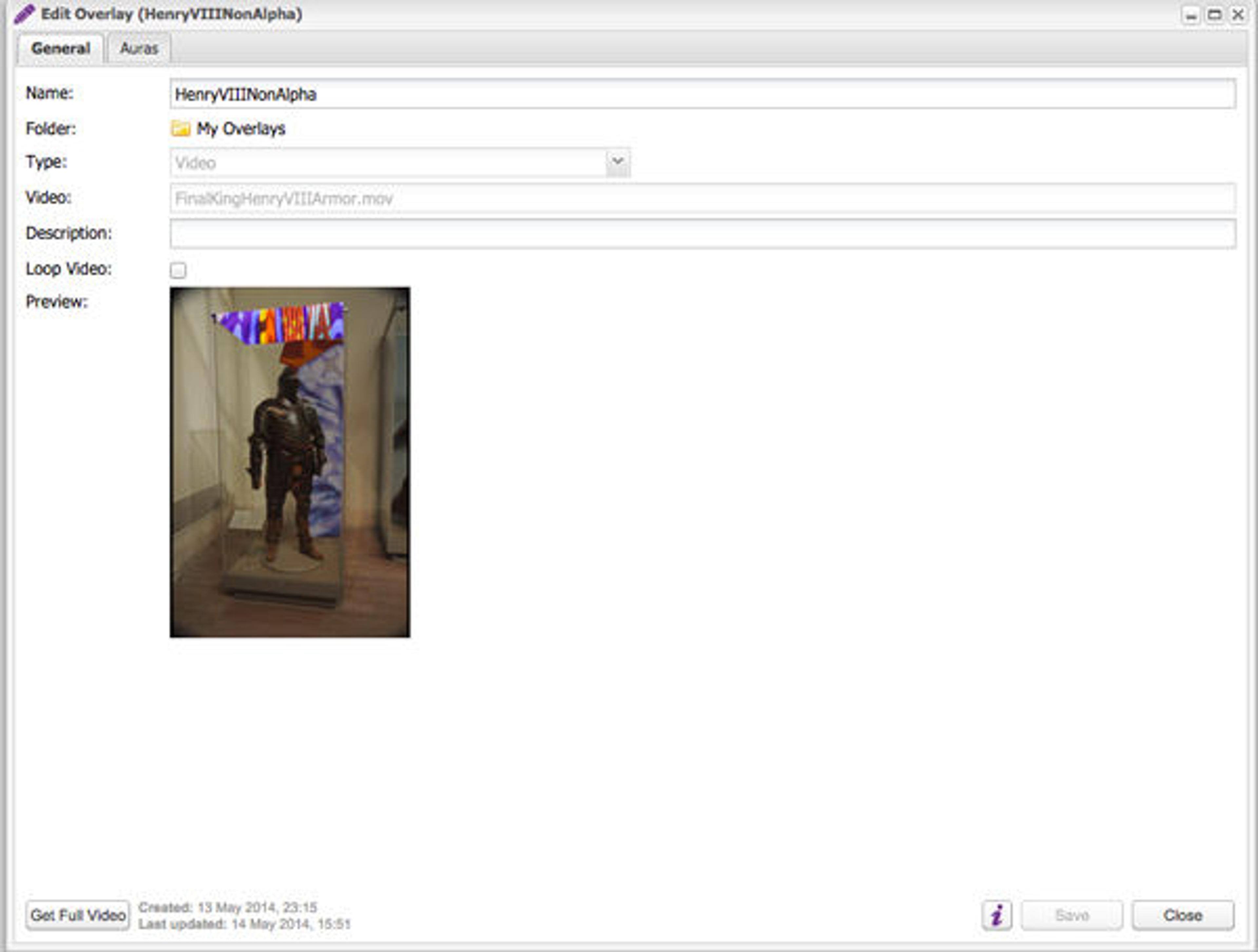

Aurasma is a free and easy-to-use application for mobile devices that allows you to create AR. We used it in different ways with different outcomes, often to showcase the work of our partnered artists. Vanessa took on the role of aura-maker-in-chief for our group. She combined objects from the Met, known as our trigger images, with our original content. With Aurasma on your tablet, you can also use one of the app's premade "overlays" (content that appears on the screen when your device's camera recognizes the trigger image) to create your very own aura to upload and share.

We created short videos, made and edited in Apple's Final Cut or Adobe's Premiere and After Effects programs, to overlay our trigger images. This sequence of images shows how Vanessa put together the aura for the field armor of Henry VIII in which Patricia overlaid patterns from Stephen Hall's paintings.

The Aurasma Studio workspace: editing and masking a trigger image

Editing an aura on to the trigger image in Aurasma

Thankfully the process of creating auras was easy enough, and we mocked up a test of our tour a week before sending viewers through. That mock-up taught us a lot about how tricky getting the right trigger image can be. According to the Aurasma website: "The best trigger images have a good amount of detail. Try to use a digital image, or a photo taken from head on. Avoid anything reflective, or anything that moves or isn't flat." Since many of the objects that we chose for our tour were sculptures, which had depth or were behind flat, reflective glass, we experienced some difficulty procuring effective trigger images.

One statue, the marble statue of Eirene (the personification of peace), proved especially problematic. The idea was that when your device trained on Eirene, a short film of Justine's collage work representing the seven chakras would be triggered. The problem was, nobody could get the film to trigger. We attempted several fixes, including using the Met's website image of the sculpture and taking multiple photos of it in situ, but it still rarely worked.

We wondered if the Museum patrons filing by made triggering more difficult. Did this activity, combined with the fact the sculpture isn't flat, mean it couldn't work as a trigger image? Attempts to mask parts of Eirene's trigger image (a process in the app by which you block off sections to ignore) were not successful at all. Finally, by including the vaulted ceiling in the trigger, the overlay finally loaded.

Our attempts at a trigger image for Eirene. Left: Marble statue of Eirene (the personification of peace), ca. A.D. 14–68. Roman copy of Greek original by Kephisodotos. Marble, Pentelic (?); H. without plinth 69 3/4 in. (177.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1906 (06.311)

The other auras were successful, but perhaps the one that created the biggest wow factor was the short film that Jason made to accompany the armor of Infante Luis, Prince of Asturias (1707–1724). The trigger image is the empty suit of armor and it unlocks a video of a young actor filling out the armor and telling the viewer a short history of his life, including the circumstances of his death at age seventeen.

Left: The trigger image. Right: An aura image from the short film created to accompany the armor. Armor of Infante Luis, Prince of Asturias (1707–1724), dated 1712. French, Paris. Steel, blued and gilt; gilt brass, silk, cotton, metallic yarn, paper; H. overall 28 in. (71.12 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Armand Hammer, Occidental Petroleum Corporation Gift, 1989 (1989.3)

While the concept and execution are notable, what was most exciting was that we were able to create a transparent aura, which meant viewers saw our actor in the background of the object's case. The steps to make this happen require that the movie be saved as an .FLV file of approximately thirty seconds or fewer, for a more efficient load time. We were able to push the time limit to around forty-five seconds, however, as we were supported by the Met's prevalent Wi-fi.

Final Thoughts

The process of building the Metaverses tour sparked our imaginations and strengthened our connections to the Met, the Westbeth Home, and our participating Westbeth artists. Our conversations about the Met's collection, about technology as a collaborative and creative tool, and about what it means to make a life as an artist in New York City have only just begun. We hope to engage in similar projects with other museums, to employ augmented reality as a means to bring new and critical perspectives into museum spaces, and to enable visitors to look more closely at the art around them.

The content for the Metaverses augmented reality experience can be accessed on the project's website.