Left: Models pose during a drawing marathon at The Met led by the author and inspired by the exhibition Court and Cosmos: The Great Age of the Seljuqs. Photo by the author. Right: Peter Hristoff. Untitled, 2016. Print on paper; 11 x 9 in.

«As my residency at The Met draws to a close, I find myself thinking about the objects, ideas, and memories that endure in our minds. Why do certain thoughts and artworks continue to hold our interest while others do not? A prolonged and intense involvement with a museum cultivates questions like this and gives us numerous examples and answers. As we all know, ideas about beauty and what makes something interesting are subjective, since cultural conditioning, education, and the media play a part in dictating what is important, relevant, beautiful, and fashionable. These are all ideas that have been pondered extensively since the beginning of the written word.»

The art of weaving has always captured my interest, particularly the knotted pile rugs of Anatolia. I find the repetitive nature of the process—the intensive labor of tying thousands of knots—reaffirms a sense of sincerity: the weaver's commitment to the craft translates into a kind of visual poetry in the finished product. Over the past several years I have become more and more involved with rug making, and I've realized that this labor-intensive, tedious, and difficult practice requires great discipline and patience. And while this is also characteristic of other types of art making, a woven work has an integrity that is very different from a painting or drawing, because it is meant to be a functional object: to be walked upon, to wrap things in, to be a divider of space. This quality in halis (rugs), combined with a traditional approach in their composition, makes me want to someday weave a rug that reads, "If it is woven, it must be true."

By "traditional approach to composition," I refer to the weaver's use of a language of symbols (which are socially and culturally relevant to themselves), often composed on a grid and then woven. The personal narrative—the expression of hopes, fears, dreams, and desires—is a tradition that is now practically lost, except in rare instances.

Most contemporary weavers in Anatolia copy existing rug designs and use patterns that are not necessarily regional, weaving compositions they themselves cannot "read" or understand. So for the last 10 years I have committed myself to creating rugs in this traditional manner and supporting such practices in Turkey. I have been fortunate to work on such a project with The Met high school interns this past year. The results of this project are rugs that display the interests of young Americans, as woven by Turkish women in a workshop in the Turkish-Aegean town of Camlik. These rugs, along with a short film documenting the weavers, HALI, are on display in the Ruth and Harold D. Uris Center for Education through August 15.

The author interviews the weavers at Can Carpet in Camlik, Turkey, about the rugs they are weaving based on the designs of The Met high school interns. A Peter Hristoff Production. Directed by Gül Ümit Erbil. View the transcript in MetMedia.

Left: Ja'lon Smith; Weaver: Eylem Ortac. Shared Root, 2016. Wool (warp weft pile); symmetrically knotted pile. Right: Paris Green; Weaver: Ayhan Ortac. Fight Like a Girl, 2016. Wool (warp weft pile); symmetrically knotted pile. Photos by the author

The interns created rugs that were inspired by works of art in the Museum, as well as personal symbols and their individual ideas and philosophies about life. Ja'lon Smith used the idea of "single source"—that all life comes from one place, no matter how different in appearance (a typical element in Islamic art)—as the inspiration for his rug about unity and equality; Aniah Bradley commented on "social constructs"; Gemmanna Gomez created a maze-like design to symbolize "the labyrinth that is our lives"; Bianca Troppman chose to combine a mixture of motifs from the place she calls home, along with a commentary on Sephardic culture and holding onto faith. Many of the students commented on ideas of empowerment and the ephemeral nature of life in their designs.

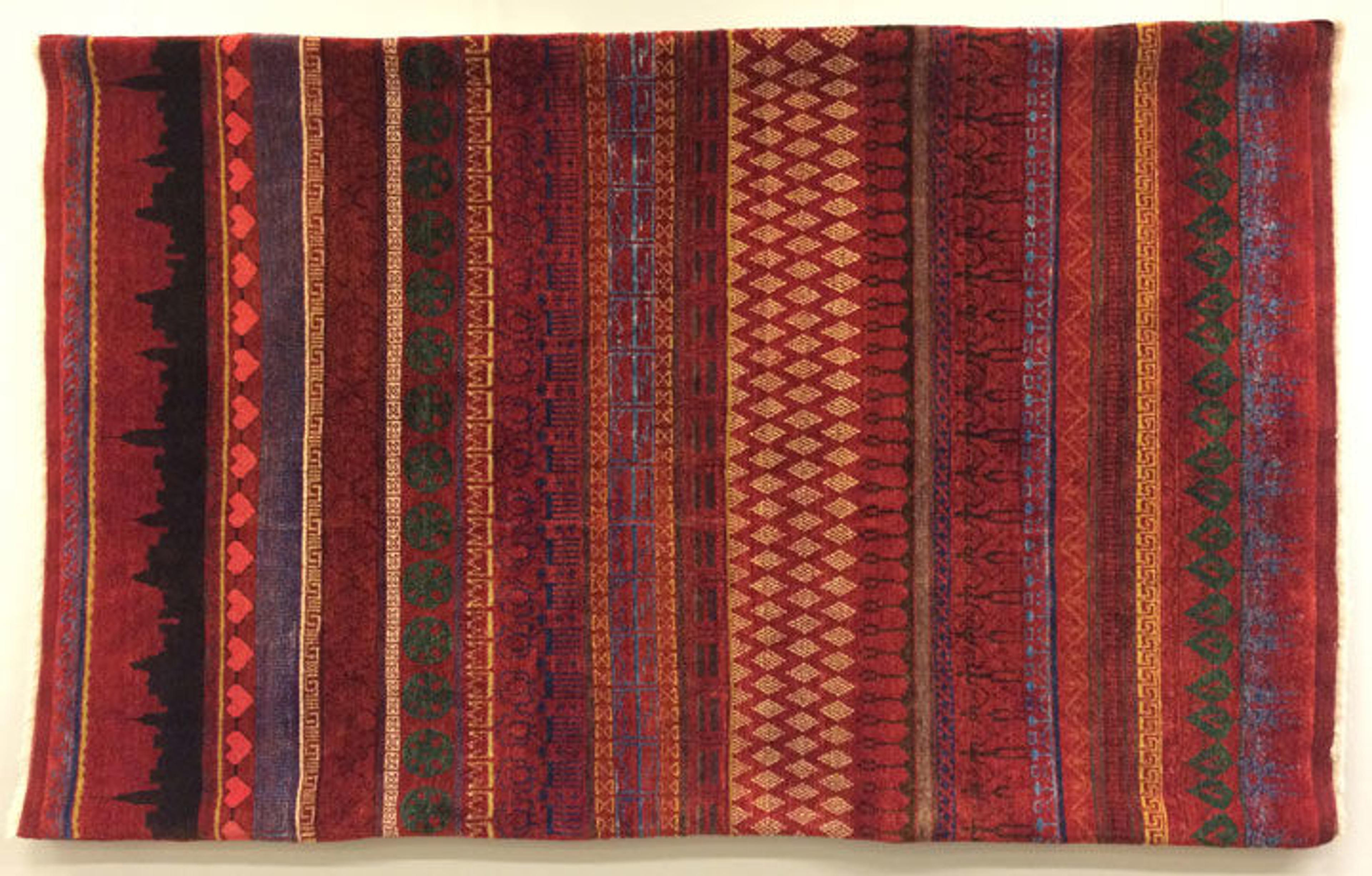

Peter Hristoff (using motifs by The Met high school interns and Education Department team). Weaver: Filiz İrgi. Untitled, 2016. Wool (warp, weft, and pile); symmetrically knotted pile

The rug shown above was composed of motifs appearing in the "minders" (small rugs) designed by The Met's 2015–2016 high school interns and the Museum's Education Department team, and a single signature motif from my own rug designs. This approach, combining motifs from various sources within a community (in this case the people involved in this project) exemplifies the tradition mentioned above—how the rug is as much about community as it is about the individual. It is this tradition of borrowing, interpreting, and integrating previously existing motifs from various sources that keeps the art of Anatolian weaving vital and of enduring interest.

My residency at The Met has, in part, been about which objects and artworks drew me in and which have stood the test of time. Which are the ones that the "untrained eye," the child and the adult, the dilettante and the connoisseur, can agree upon? Which are the artworks that may not have a common denominator with all viewers but cast a magical spell on all nonetheless?

Over the course of my residency, I came upon numerous works at the Museum—from objects in the Cypriot galleries to ceramics from Korea—that I believe have this quality. The incredible bis poles of the Asmat people seem to take everyone's breath away, but why is that? The many aspects of works in The Met collection—the colors of a Van Gogh, the glow of a Rembrandt, the ferocious beauty of power figures from the Congo—convert the Museum into a house of mirrors, a place that reveals what we know and suspect about ourselves. Our reflection can either be distorted or crystal clear, but is always us.

Many thanks to The Metropolitan Museum of Art for allowing me to gaze into so many mirrors and then asking me what I saw.

Related Links

Exploring What Matters: Art by The Met High School Interns, on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through August 14, 2016

Read all blog posts related to Peter Hristoff's residency at The Met.