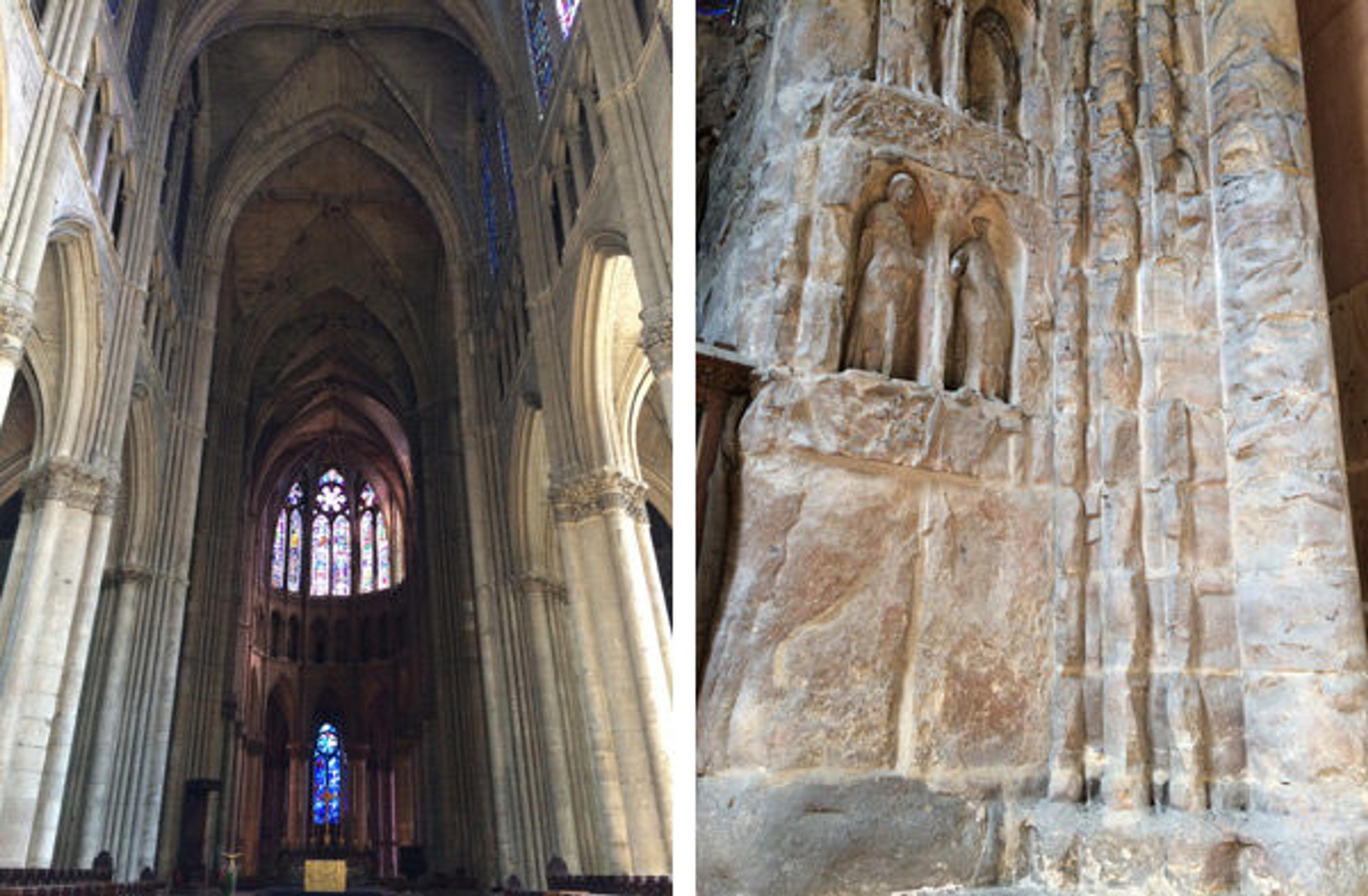

Left: Reims Cathedral, interior, looking toward the choir. Right: Reims Cathedral, interior of west facade, showing fire damage from World War I. All photographs courtesy of the author

«In recent weeks, my colleagues have shared tales from their summer travels. My trip took me to Paris, where I made excursions to several medieval monuments that are experiencing ongoing restoration work, which provides unusual access to see them up close. (Scaffolds are a good thing!) The most exciting visit was to Notre-Dame de Reims, or Reims Cathedral, in the heart of the Champagne region. Not only is it one of the canonic Gothic cathedrals of the thirteenth century, but it is also the subject of the dissertation that I completed some years ago.»

This magnificent structure—whose construction began in 1211—was the cathedral where French kings were crowned and anointed until 1825. The cathedral is often featured in movies about Joan of Arc, the maiden heroine during the Hundred Years' War who famously accompanied Charles VII, in 1429, to Reims Cathedral for his coronation. Its symbolism in the French national memory is one reason why it suffered extensive damage during World War I, the evidence of which is still visible today.

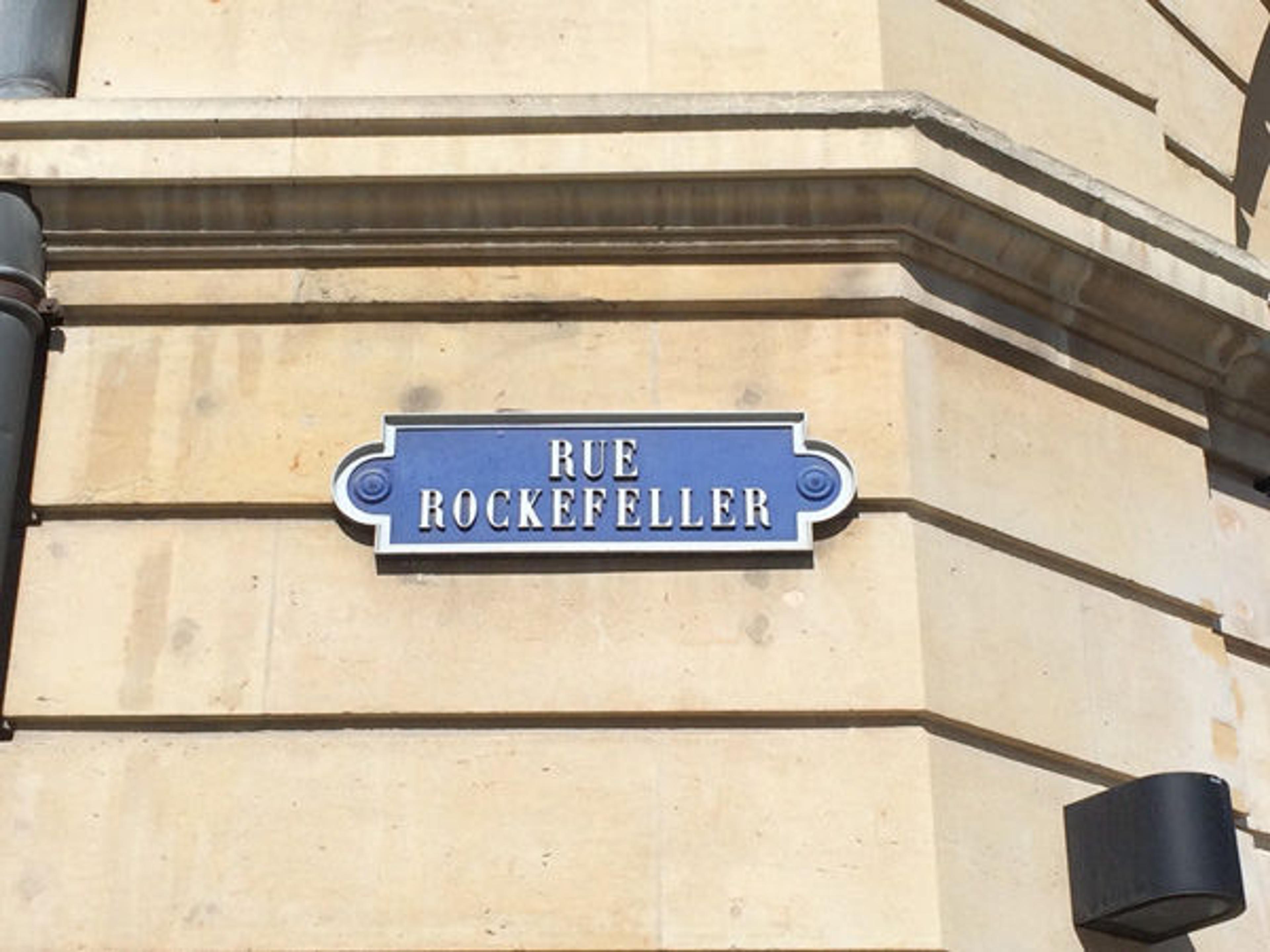

A sign for "Rockefeller Street" across the plaza from the cathedral

The historic center of the city of Reims was subjected to constant shelling during World War I, which caused numerous fires and massive destruction. The municipal library near the cathedral, for example, was rebuilt after the war with money from Andrew Carnegie, and thus renamed "Bibliothèque Carnegie." The cathedral's completely destroyed roof was replaced with the help of a generous donation from John D. Rockefeller, Jr., the benefactor of The Cloisters, and as a result, a street facing the cathedral's west facade is named after this American philanthropist.

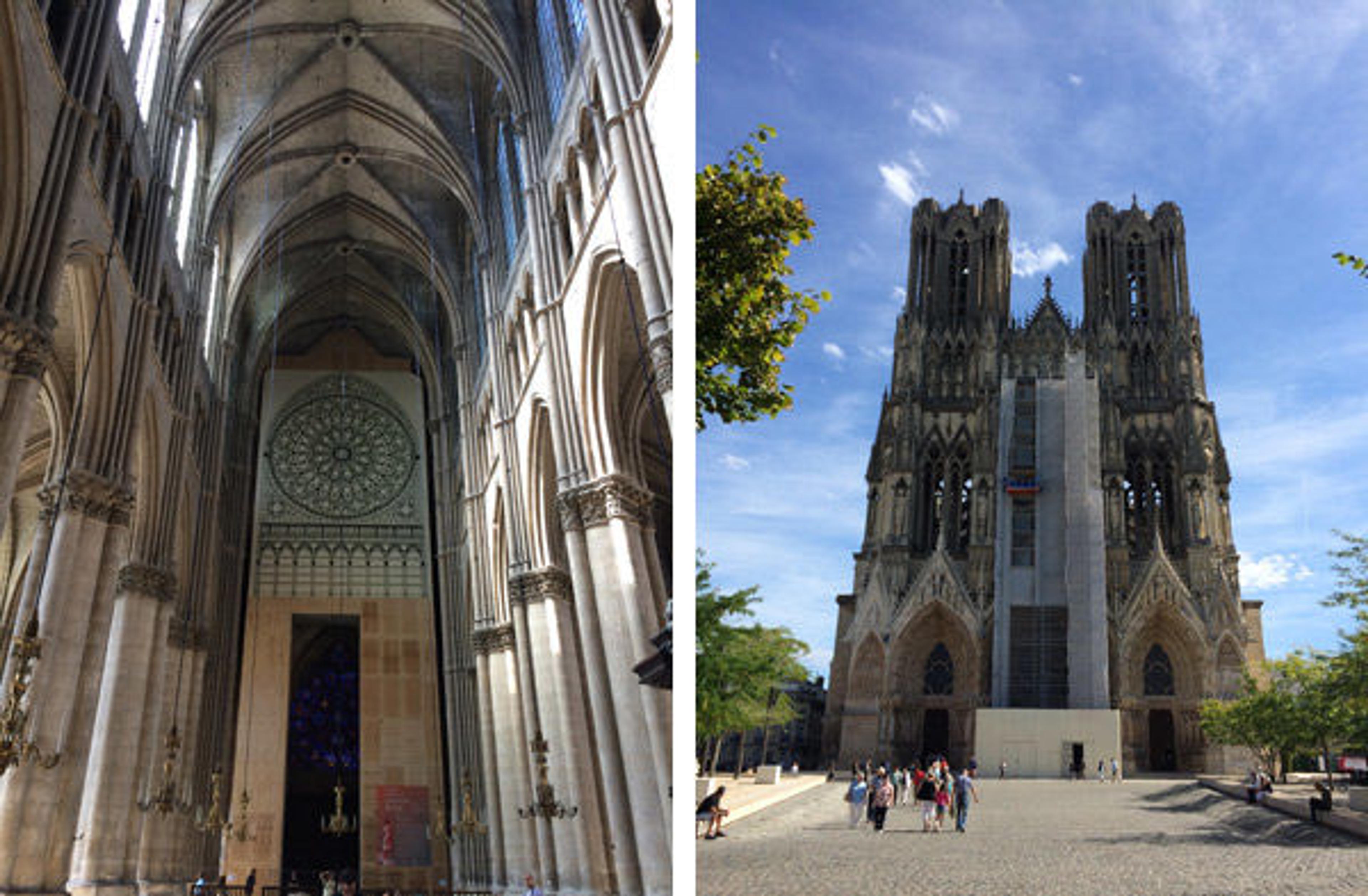

Left: Reims Cathedral, interior of west facade, with scaffold hidden behind plywood protection. Right: Reims Cathedral, exterior of west facade, with scaffold against the central bay. The construction elevator is visible at the level of the rose window's apex.

The primary purpose—and excitement—of my visit was to get on the scaffold now covering the interior and exterior of the west facade, which was erected for an extensive restoration of its magnificent and enormous rose window. I received permission to enter the work site through a French colleague, so I put on a hard hat and rode the elevator to just about the level shown in the above right photograph.

While all the stained glass had been removed for cleaning and restoration, there was much to see about the metal armature used to secure the stained glass to the rose window. The masonry surrounding the window has suffered various degrees of damage and is being repaired, replaced, and meticulously documented.

The center portion of the rose window's exterior, with masonry arms radiating outward to form the gigantic circular window that dominates the west facade

Each level of the scaffold is more than two meters high. When viewing from the ground, as we normally do when visiting a building, it is simply impossible to appreciate the enormity of the window, the thickness of the masonry, the elaborate network of metal armature, and the exquisite carving that is so many meters above us.

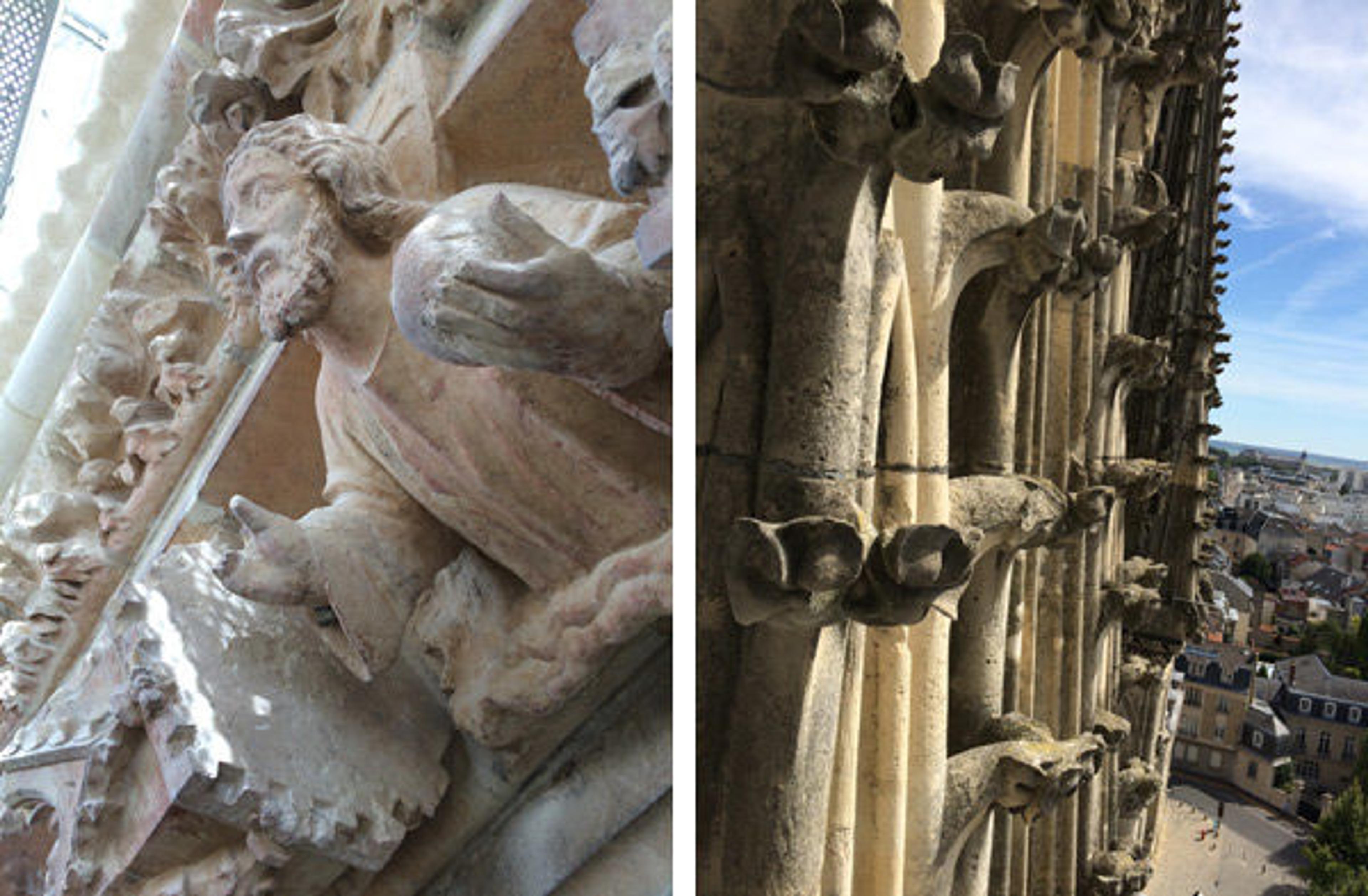

Left: Christ figure at the apex of the rose window. Right: Crocket decorations of the exterior

It is difficult to adequately describe the admiration I have for the sculptors of the thirteenth century when looking at this Christ figure at the apex of the rose window; nor is it possible to describe the awe I experienced when I was within touching distance of the facade gables. By necessity, we study historical architecture from images shown in classrooms, now often in 360-degree panoramic views, but nothing compares to the sensation—one which is one hundred percent visceral—of being in a building site and experiencing the scale, texture, and even the light coming in through the windows.

Similarly, no reproduction can replace the thrill of standing in front of an object in a museum, where one experiences the object's perfections and flaws all at once, and when an intimate dialogue between the viewer and the object takes place.