Met curator Denise Allen and clinical psychologist Jared O’Garro-Moore, PhD, discuss Spinario (ca. 1501) by Antico.

Facing Pain

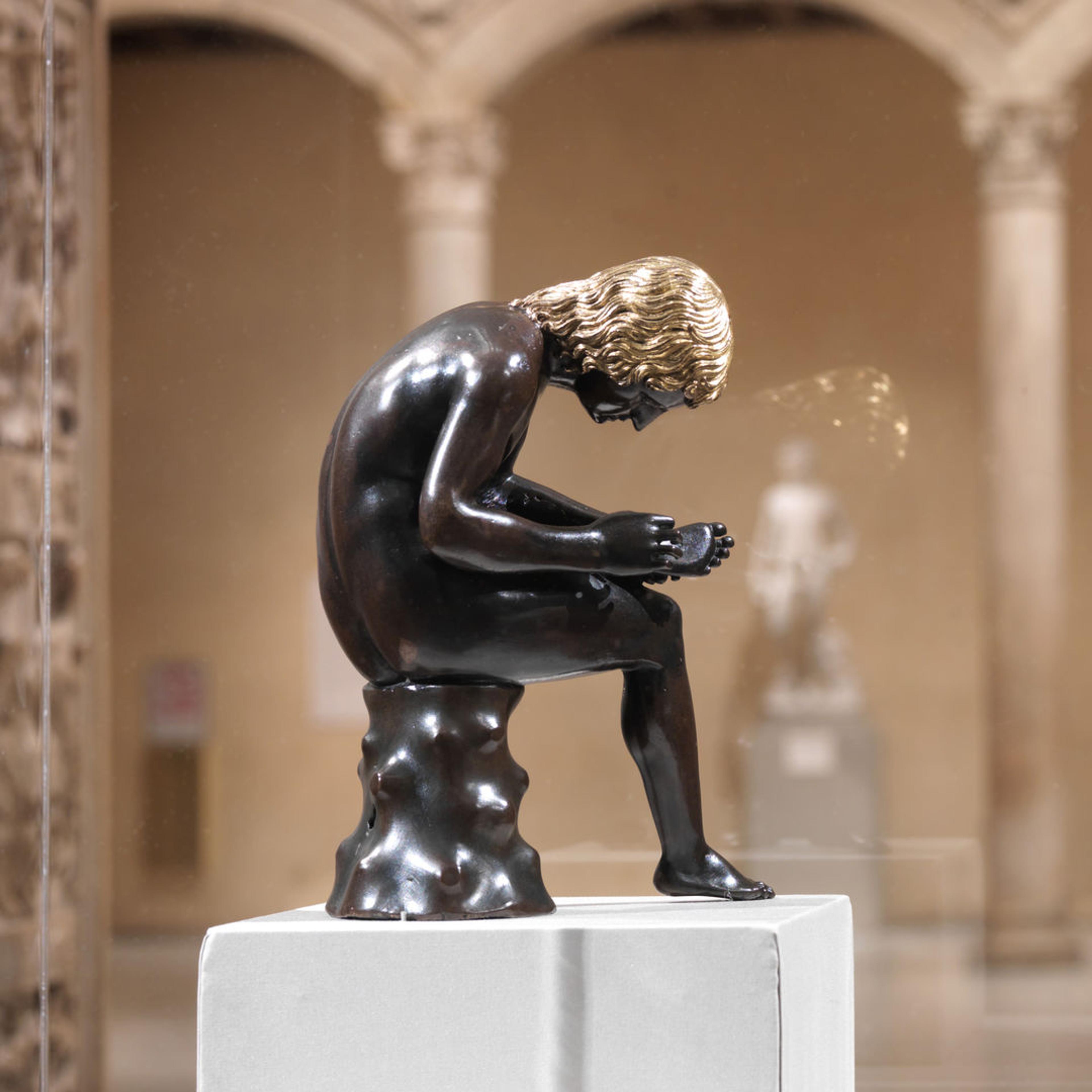

Spinario (Boy Pulling a Thorn from His Foot)

Listen to the conversation, learn more the artwork, and read the transcript below.

Antico (Pier Jacopo Alari Bonacolsi) (Italian, ca. 1460–1528). Spinario, (boy pulling a thorn from his foot), probably modeled by 1496, cast ca. 1501. Bronze, H. 7 3/4 in. (19.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Charles Wrightsman, 2012 (2012.157)

This statuette, which is only seven and a half inches tall, is a small version of a life-size, ancient, bronze sculpture of a boy pulling a thorn from his foot. It was made by the artist nicknamed L’Antico, which means “one of the ancients.” He made sculptures after well-known ancient Roman sculptures. He did them so well that he was thought to be equivalent to the masters of ancient Greece and Rome. The Spinario is one of his greatest works.

Transcript

DENISE ALLEN: I’m Denise Allen, curator of Renaissance and Baroque sculpture at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

JARED O’GARRO-MOORE: And my name is Dr. Jared O’Garro-Moore. I’m assistant professor of clinical psychology in the psychiatry department of the Columbia University Irving Medical Center.

—

ALLEN: I think many of you listening will be wondering why a little, bronze figure of a boy pulling a thorn from his foot is an arresting object today. So I think that’s how we can open our conversation.

O’GARRO-MOORE: Yeah, thanks Denise. As a psychologist, I’m all about being able to embrace pain and embrace difficulties as they come up in life. And so when I look at this sculpture, what I’m seeing is this person who is really embracing this notion of acceptance, right? He’s really intently looking at this thorn in his foot. And so there is this acceptance that in order to move forward he has to actually take care of this painful thing in his life currently.

ALLEN: It’s the anticipation of the act that makes this work so powerful. His hand is poised above his heels and his toes are spread in anticipation, but his face is impassive. He looks very calm.

O’GARRO-MOORE: Our minds are very powerful things. When we go to the future, we’re able to kind of plan for different things. We’re able to come up with contingencies. It’s a very like unique skill that we as humans have. The problem, though, is when we stay there for too long is that we also can think about catastrophe. You can also kind of get lost in the ways in which things can go wrong. And anxiety tends to come from that. And similarly, being able to think about past events and think about what happened when, come up with cause and effect. But if we kind of stay back there, in the past, things like guilt, things like shame, tend to come up, right? So I think the important piece here about being able to kind of pull your mind back to the current moment, it’s such a strong and useful skill and it is like the basis of mindfulness, right? Being able to pay attention on purpose.

ALLEN: One of the other beautiful things about the Spinario is that he seems to suspend time. And for me, that’s calming. Does that relate in any way to how one deals with, with pain or with any kind of anxiety or distress?

O’GARRO-MOORE: In terms of mindfulness and pain, we know clinically is that when we get people to try to focus in on their pain, but come from it from a place of acceptance and willingness, and being able to just be curious about it, rather than trying to fight against it or trying to solve it, then they find that their pain kind of can fluctuate up and down.

They allow it to be able to yes, get a little worse at times, but also, decrease. And so what we ask people to do is actually okay, like really like, look at that pain, what are you noticing about it? Instead of taking that stance of, “I have to get rid of it, this is something I need to problem-solve right away.” And in some ways the Spinario is kind of a metaphor for that, right? Because it is really just, in some ways a calm, kind of curious, look at this thing that is painful.

ALLEN: Yeah, you can’t be curious if you’re not on some level accepting. And that really does also, I think add another dimension to understanding the power of this figure of the Spinario. If one commits to facing one’s pain, as does the Spinario, if one settles into that, at that moment, does it make one vulnerable? Is that part of the Spinario’s message?

O’GARRO-MOORE: Possibly, I mean, here you have a sculpture in which this person has committed to letting that bad feeling come up, and letting it be. And I absolutely think there's a vulnerability there. And, I don't know, I think in some ways there is a lesson to be learned.

ALLEN: That brings me to the question, you know. When people face pain, I know it’s important to have help, but is it something that one must do, in a sense, alone?

O’GARRO-MOORE: I think one can make a case for both sides of that, right? I mean, your pain is your pain. And as the audience, we’re also looking at this and there’s something to being able to empathize, right, with pain, because we all do know what that feeling is like.

ALLEN: Yeah. The other thing is, as someone who is, you know, an art historian, dealing with a lot of sculpture all the time, one tends to interact with the figures and sometimes a figurative sculpture will address its audience. The figure will look at you or gesture towards you. And one of the things that I find so compelling about the Spinario is that the audience is utterly irrelevant. He is aware of what he needs to do and that is pull the thorn from his heel. But he’s not doing it for anybody but himself. He’s completely contained within that moment.

O’GARRO-MOORE: And for you, when you look at this sculpture and you see, like, this person is really riveted to the now, right? There’s nothing else. This person is doing one thing at a time, is being very intentional. And do you think that relates to how distracted we can become so easily?

ALLEN: Yeah. I mean, I’m a true believer that multitasking is not exactly natural to human beings. And what the Spinario and works of art, you know, really give to me is that in order to appreciate them, to understand them, I need to slow down. I can’t just walk by. I just can’t flick my gaze at the Spinario and get anything from it. Works of art give back, when they are given time. And that is the only way they give back. And that goes from, you know, the cave paintings of Lascaux all the way up to the most contemporary works of today.

###