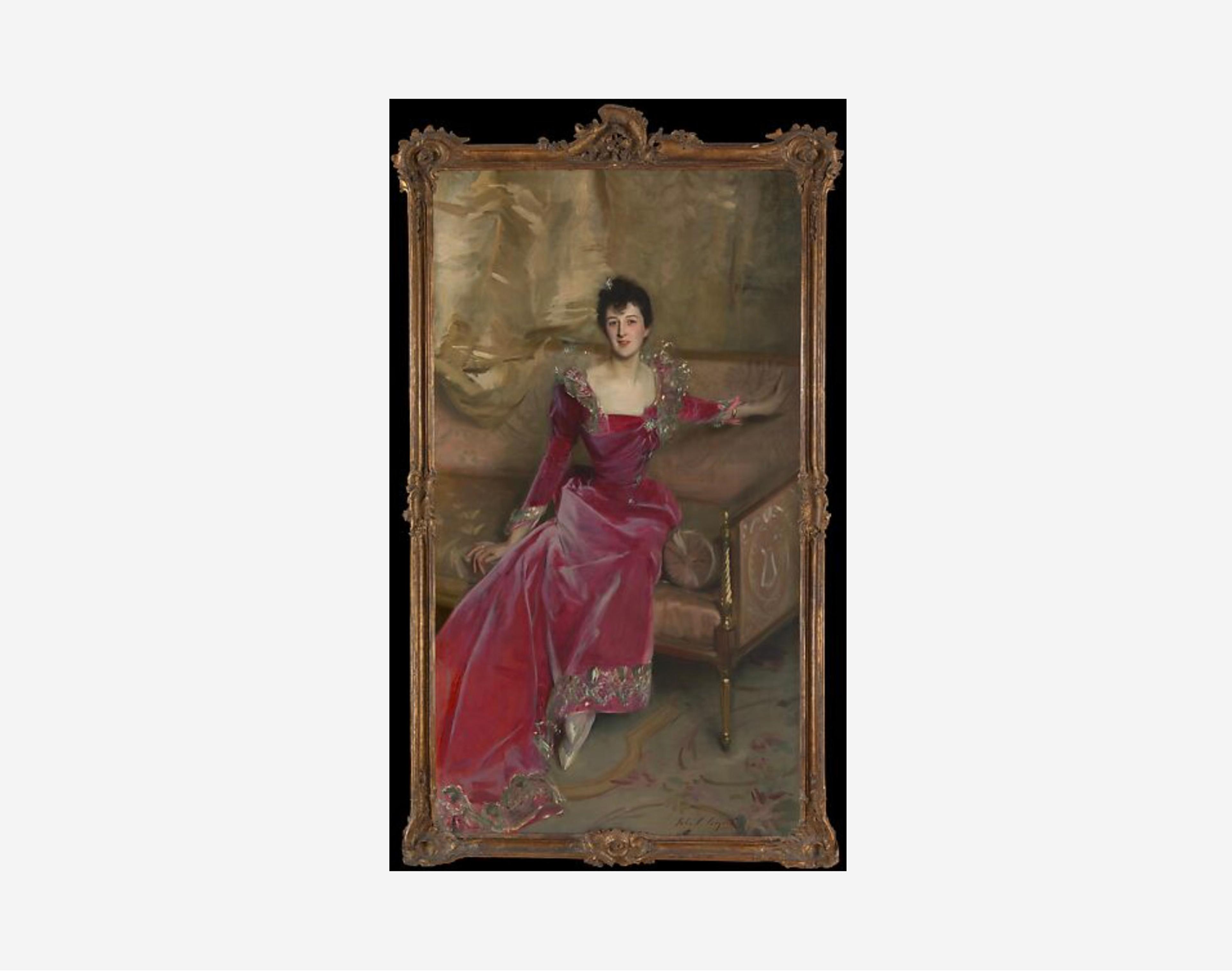

John Singer Sargent (American, Florence 1856–1925 London). Mrs. Hugh Hammersley, 1892. Oil on canvas, 81 x 45 1/2in. (205.7 x 115.6cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Douglass Campbell, in memory of Mrs. Richard E. Danielson, 1998 (1998.365)

The volume's turned up too high on so much of this stuff, to the point where we can almost recognize the absurdity of it.

My name is Kehinde Wiley.

I make paintings—portraits, primarily—of young African-American men and women. My work and Sargent’s intersect with some of the problematics surrounding class. In his day he was commissioned to make portraits by some of the most celebrated families in the world.

I’m a young black man trying to deal with the ways in which colonialism and empire are all in these pictures, but they’re fabulous! It’s a guilty pleasure. The seduction is there. Sargent is probably one of the best painters I know because he’s able to make it look so effortless. Look at that table: the masterstroke of the highlight. What’s little known is that Sargent would make that masterstroke and if it wasn’t just quite right he’d wipe it off.

Let’s not doubt that these are high-priced luxury goods for wealthy consumers. You look at these amazing sisters in the foreground, but what we also see in the background is a family portrait that points back to the history. And so it’s about painting convincing us about our undeniable place in the world.

There’s a power relationship here. You’re standing in front of this gorgeous woman at this insanely large scale. Where would you be if you were in that room? You’re on your knees.

All of these paintings were incredibly important social occasions. And so you get the best gowns made, you have your hair done to the nines. The powdered faces and pearls and all of that regalia becomes part of this grand show. These people have been preparing their entire lives for this moment, and here it is.

If you look at the eyes, there’s a desire to please the artist himself. As opposed to correcting for that, Sargent paints the performance. The volume’s turned up too high on so much of this stuff, to the point where we can almost recognize the absurdity of it.

Generally I enjoy painting the powerless much more than the powerful. My relationship with the art-industrial complex is a very troubled one. Many of the people who are in my paintings can’t afford my paintings. There’s a conundrum there.

I try to establish a kind of cold neutrality. The cruel indifference of history itself has to be echoed in the enterprise of painting, the strange history in which so many people who are black and brown don’t happen to people the great museums throughout the world.

My work is not about opining; it’s not about looking at the past and longing for that to be something different. I’m interested in using the past in order to break open into the present day.

So many people will look at a simple portrait like this and they'll say, “You’re making so much out of nothing.” And I disagree. I think that there is a universe being pointed to here. It’s something that you can see if you’re interested in looking that way.