The sound of flutes paired with scenes of animated fountains introduces the film Metropolitan Overview: A Proposal for a Central Guide to the Collections of The Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Eames Office, spearheaded by husband-and-wife designers Charles and Ray Eames, produced it as part of their proposal for the Museum’s then-Director Thomas Hoving in 1975.

Still from Metropolitan Overview (1975). Courtesy of © Eames Office, LLC. All rights reserved.

Hoving commissioned this project at the beginning of “the Museum’s second century” with hopes of providing unconventional information access to the collection during an era in which computers were rarely present in museum settings. Submitted just after The Met opened the Robert Lehman Wing, Metropolitan Overview arrived when the Museum could focus more attention “not to growth, but to development.” There was an immense desire from the Eameses to illuminate the culturally dense, communicative landscape that was quickly flourishing in and outside the Museum.

The first component of the proposal was an intricately structured architectural model detailing a redesign of the Museum. The plan would transform the monumental collection by adding a new wing, updating the foyer, and adopting technology-laced educational elements. Metropolitan Overview, the film, was delivered in tandem with the model. It was a communication device intended for The Met’s staff, adding layers of visuals, rationale, and emotion to the voiceless architectural model. In the film, moving images of the plan’s model grazed past one-inch scale people frozen beneath miniature museum arches. These lifelike visitors admired films on small-scale screens in the galleries and researched artworks via computer terminals. In between the model and live-action scenes of museumgoers enjoying displays were periodic jumps to cherished artifacts—the objects that brought them to the Museum in the first place.

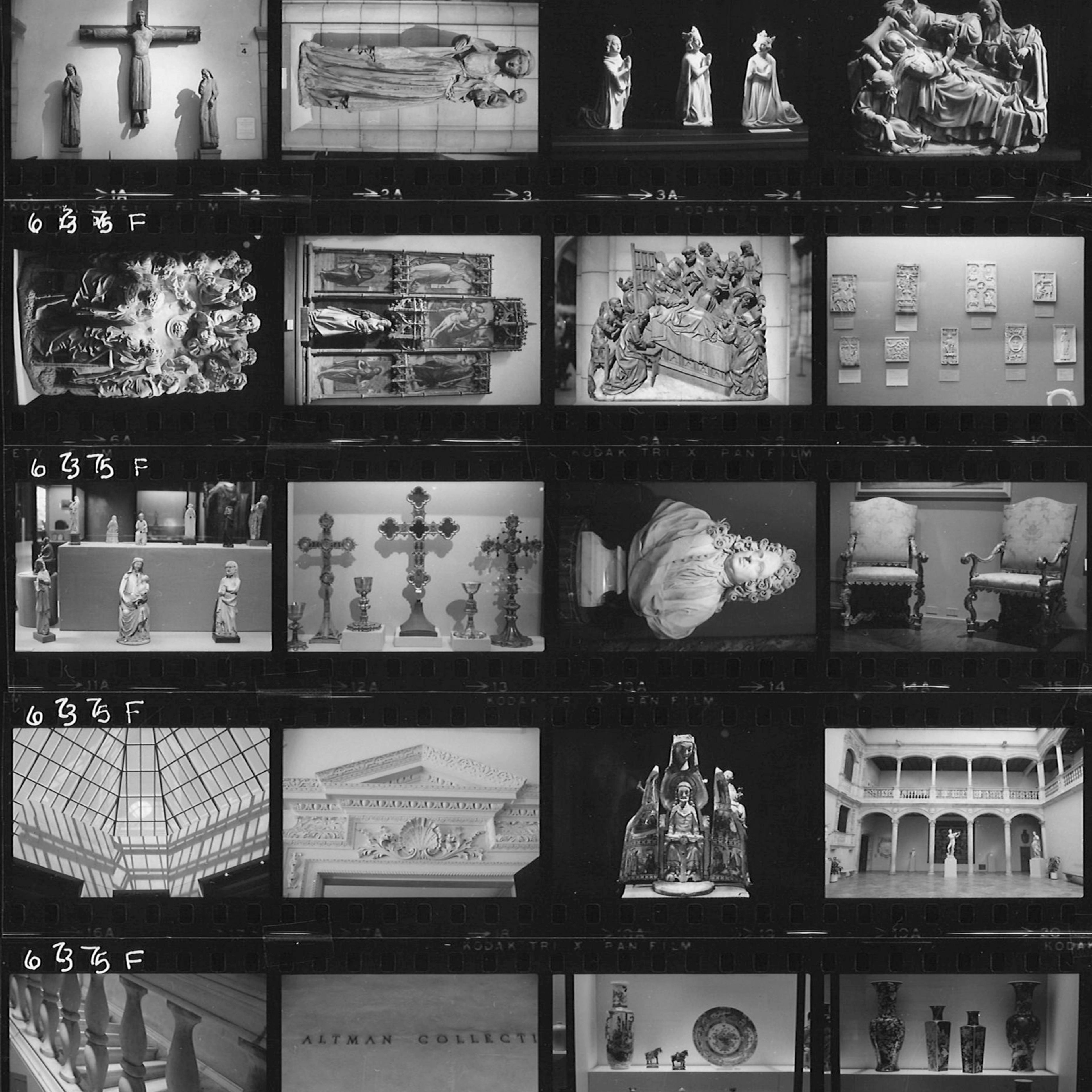

Various corners and objects of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, as photographed by Charles, Ray, and the Eames Office staff during the research and making of the film, 1975. © Eames Office, LLC. All rights reserved

The timing of this project coincided with the opening of a three-year, Eames-designed traveling exhibition celebrating the American Revolution Bicentennial. The World of Franklin and Jefferson (1975–77) toured internationally from Paris to Warsaw to London. Then, in March of 1976, the exhibition opened at The Met before continuing its North American travels.

Hindsight tells us that Charles passed away two Augusts later, making these Met-related projects among the final ones of his life and work partnership with Ray. As the two designers’ careers are a charted path of learnings, teachings, and experience, one can follow a thread to arrive succinctly at Metropolitan Overview. While doing so, it’s clear that the Eameses’ four decades of shared work made them infallible candidates for proposing the Museum’s renovation.

Charles and Ray in London during the tour of The World of Franklin and Jefferson exhibition, one month before its arrival at The Met for installation. Photograph by Ian Cook for Observer Magazine, October 1975. © Eames Office, LLC. All rights reserved

The Eames Office

Charles and Ray Eames and their design office in Venice, California, made their international mark with their furniture designs. Before designing chairs—and also during years of heavy furniture production—their curiosity turned fervently toward other media: filmmaking, photography, architecture and interior design, toys, lectures, World’s Fair presentations, and exhibition design. Their attention spanned far past four-legged seats; spinning tops caught their eye, as did wounded soldiers during WWII. Students were important, especially children, and play was a necessity, even for adults. There was a strong possibility that a visitor to the Eames Office could hear Ray speaking about mathematicians or find Charles admiring a wall of the office through the lens of a kaleidoscope.

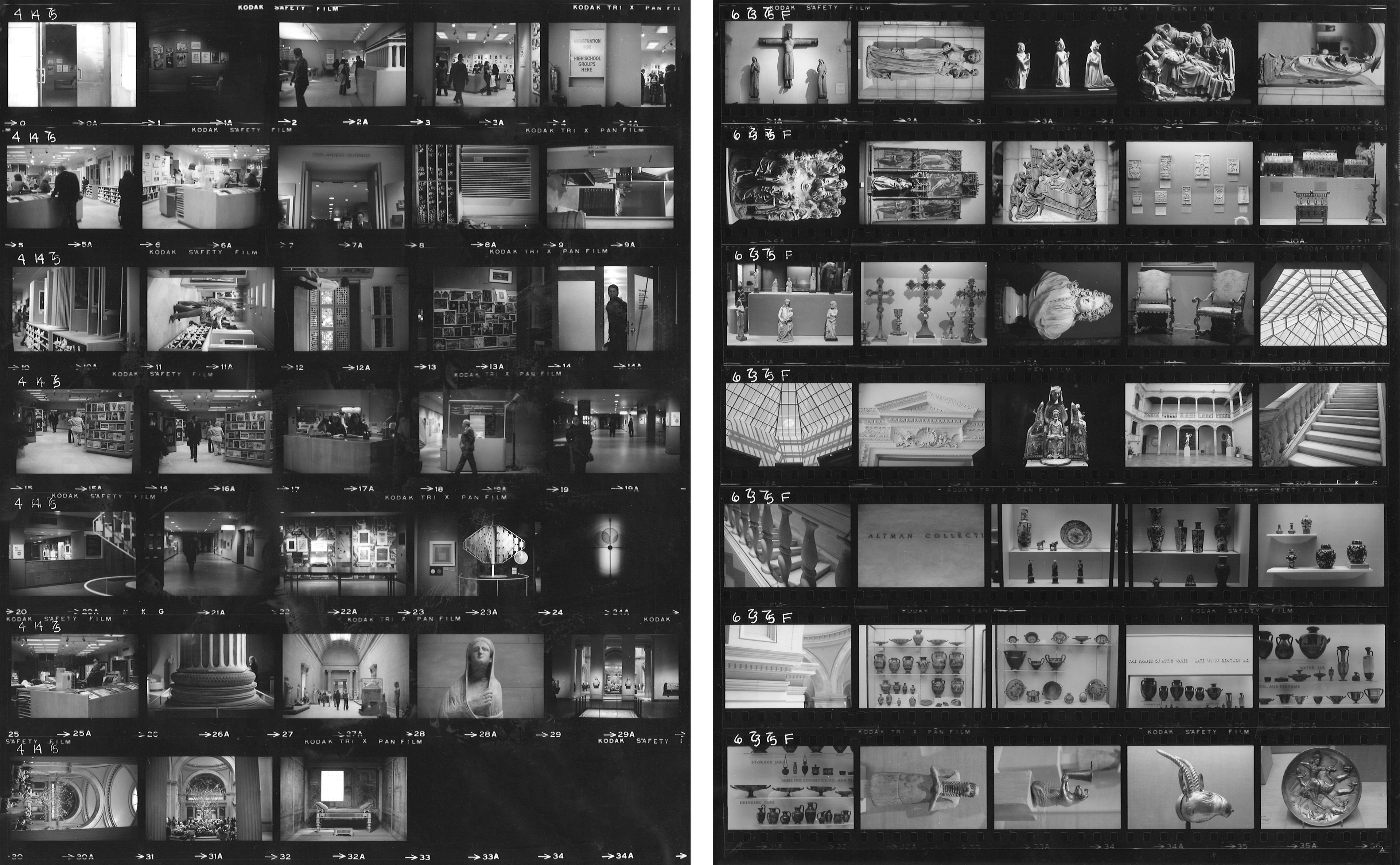

Four productive, colorful decades of design work existed inside the Eames Office in Venice, California. Charles and Ray share the Eames Lounge Chair and Ottoman while surrounded by their staff. Photograph taken for Vogue magazine, August 1959. © Eames Office, LLC. All rights reserved

The couple’s practice was expansive, and it was their philosophy to share it democratically. “Good design” meant catering to how people are similar to one another instead of addressing their idiosyncrasies. Successful education requires distilling the most complex ideas into their simplest parts. Good design equaled universal understanding.

On being a good host

“The Museum is set out to implement the comprehensive plan,” declares the narrator of Metropolitan Overview, proceeding to describe a scheme that “[organizes] its galleries and [presents] its exhibits in a way that will offer a new level of hospitality for the out-of-town visitor, the child growing up in the city, the citizen, and the scholar.” What feels starkly Eamesian about these words is the commitment to being “a good host anticipating the needs of his guest.” Charles and Ray extended this philosophy to all aspects of their life and work.

If you’re seated in an Eames chair, you are the guest of Charles and Ray.

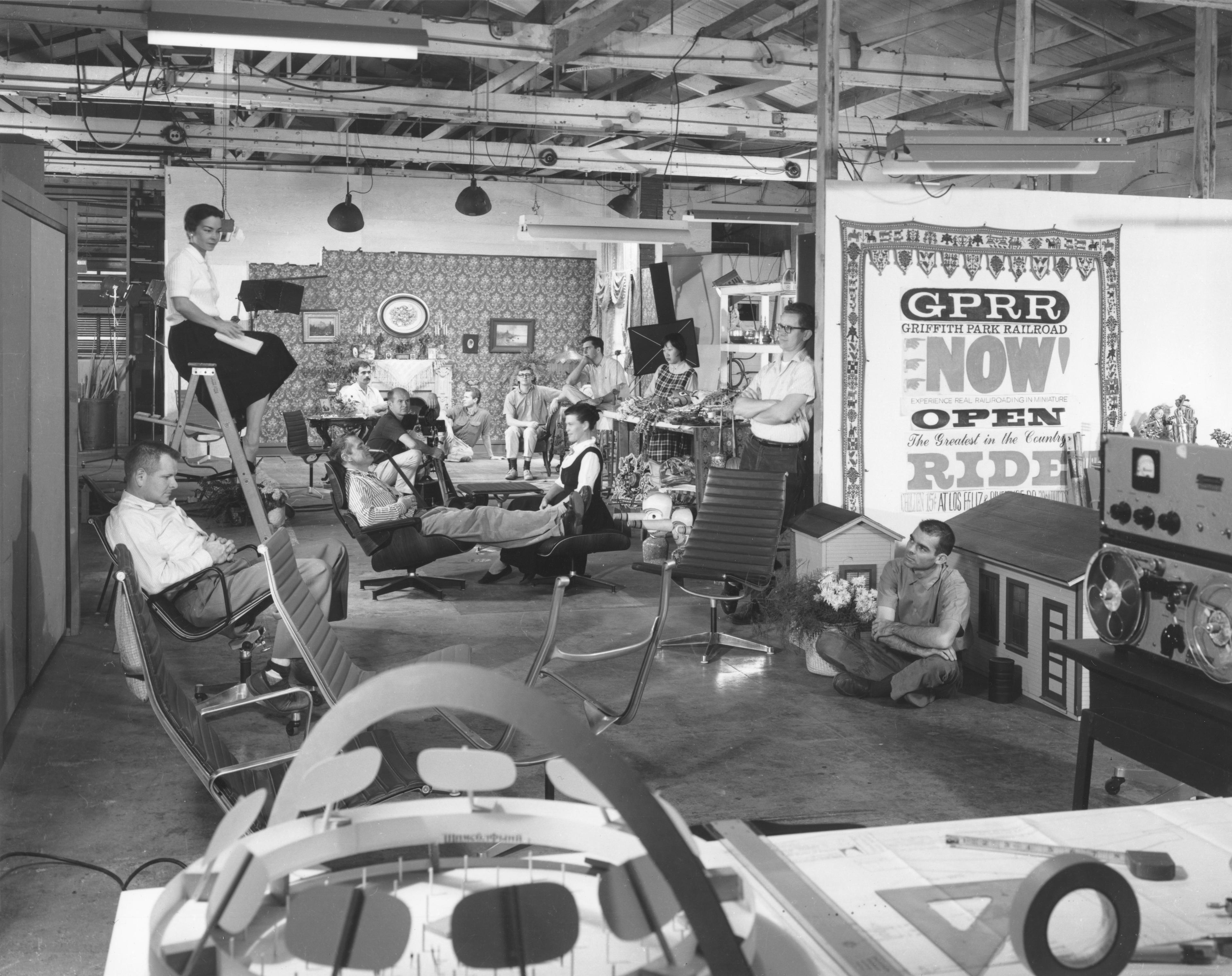

Those visiting the Eames Office and Eames House were gifted the ultimate level of care and attention. Guests were often presented with layered patterned table linens; candles burned purposefully to desired heights; delicate flowers were arranged peculiarly; and every condiment, jam, and flower was nestled in its own vessel. Theatergoers watching an Eames film, such as visitors to the American National Exhibition in Moscow in 1959, were their guests for twelve minutes. Eames Demetrios, one of the duo’s grandchildren and today Director of the Eames Office, calls attention to another form of hosting: “If you’re seated in an Eames chair, you are the guest of Charles and Ray.”

Left: Entertaining IBM management, including I. Bernard Cohen, at the Eames House, 1973. Photograph by Ray. Right: Glimpses of the U.S.A. at the American National Exhibition in Moscow, 1959. © Eames Office, LLC. All rights reserved

It’s interesting for the Eameses to view this guest-host relationship with New York at the center, looking closely at the Museum hosting the city’s people. When designing their own home—a process that began in 1944—they described the house’s surrounding sea and eucalyptus meadow as a “re-orienter and shock-absorber” of the stresses of modern life. In Metropolitan Overview, the museum promises an emotional cushioning from the hectic, noisy life of the urban landscape beyond its walls.

Films and technologies as devices for learning

Films, the finesse of machinery, and fine art were at an intersection in the minds of Charles and Ray. New York’s Museum of Modern Art was one of the first locations to debut Eames furniture in 1946; the Eameses illustrated the history of the Smithsonian Institution in moving images; and they directed individual short films exploring the art of Cézanne, Degas, and Picasso. At the heart of these projects was the idea that technology—the camera, furniture tooling, or the computer—could be perfectly entwined with art and design education. Metropolitan Overview was presented alongside an architectural model, exactly mirroring the relationship between technological elements and the Museum’s physicality. Unfamiliar technological features would not replace handmade histories but bolster them instead.

The Eameses produced Degas in the Metropolitan to highlight a 1978 exhibition of the artist’s paintings, sculptures, and drawings. To create the film, Charles and Ray recorded 35mm slides using “a new computer-managed motion-control system.” © Eames Office, LLC. All rights reserved

Within the new "Information Hall" of The Met would be a series of activities that seem ordinary by today’s standards. Guests would use computers to search the Museum’s catalog, while other terminals printed customizable tour pamphlets. Screens in the gallery space would display citywide events and breaking news in the art and archaeological communities. Public versus private space was also at work inside the hall: glass kiosks served as miniature film screening rooms for smaller groups of people because, as the narration notes, “There are some ideas which can best be presented on film to an isolated viewer who is willing to be held for a few minutes by a single topic.” Through these activities, visitors could gravitate to what interests them best, leading to a stronger personal connection with the collection.

Related to this portion of the renovation, the film described the “scale and richness of the Museum” and its ability to create “an immediate experience for the seasoned museumgoer and others.” This was an opportunity for The Met to share the importance of art with the masses by embracing the strengths of computer technology and filmmaking.

Collaged storytelling

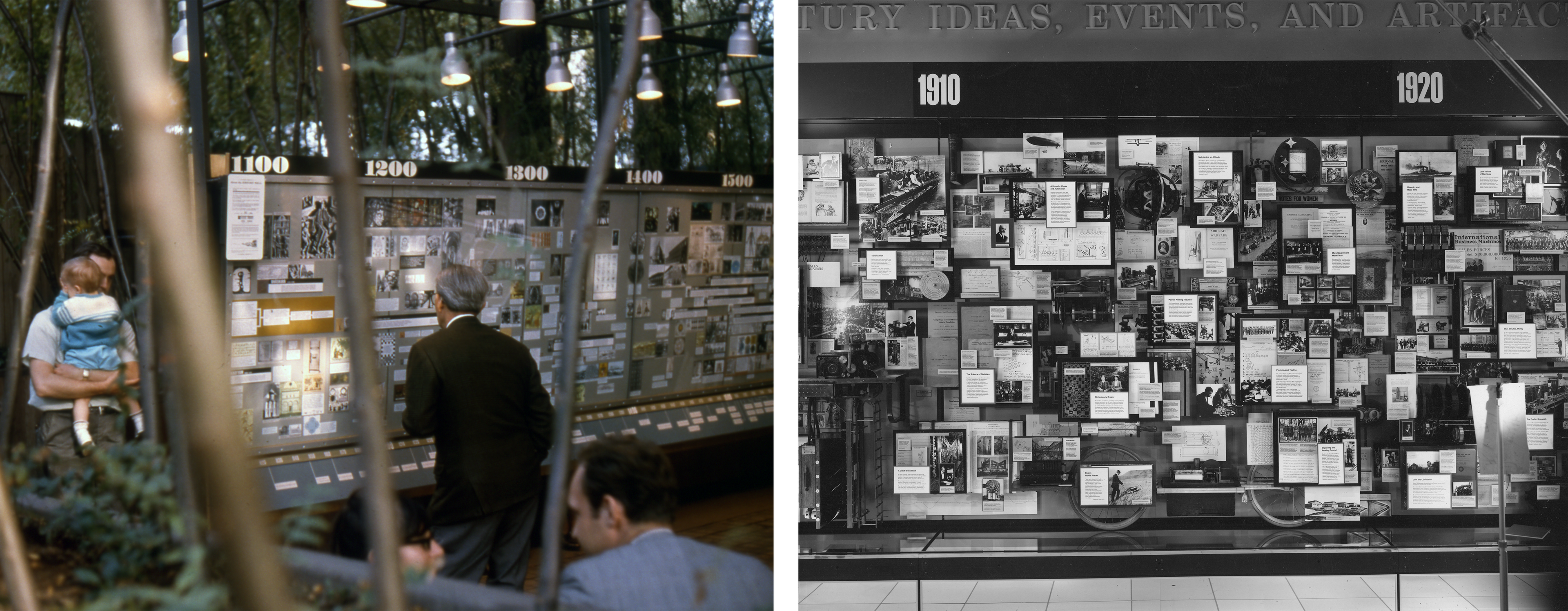

Timelines were a fundamental part of Eames exhibition designs and were often enormously scaled to cover complex histories. Metropolitan Overview weaves viewers around a three-dimensional timeline that guests could walk through. Objects long kept in storage were intended to be scattered throughout the timeline, paired with imagery, stories, and “patches of information” about the collection.

This timeline was a crucial component of the Museum’s Information Hall, proving to visitors that “the treasures of the Museum are more than just one precious thing after another.” Instead, the displays would showcase objects from “successive and overlapping civilizations,” pieced together much like a collage.

In 1961, the Eameses revealed the exhibition Mathematica: A World of Numbers…and Beyond at the California Museum of Science. Several duplicates were created, including a site-tailored display for the Eames and Eero Saarinen–designed IBM Pavilion at the 1964-65 New York World’s Fair. Each iteration of Mathematica’s anchor was The History Wall timeline, a fifty-foot information-dense collage that acted as a storytelling element. Charles explained this exhibition trick in Ameryka magazine in 1971: “We expect [The History Wall] to be meaningful at almost any level. A schoolchild can look at the wall and see that the history of computers comes from getting on with the processes of life. Specialists will find inside jokes and rare memorabilia that only they will recognize. In between, of course, there is the great lay public.”

Left: An iteration of Mathematica’s timeline at the IBM Pavilion of the New York World’s Fair, 1964. Right: A dense, three-dimensional Eames timeline at the exhibition A Computer Perspective, sponsored by IBM in 1971. © Eames Office, LLC. All rights reserved

An Eames-designed collage of physical materials, visuals, and text aimed to give the feeling of fantastical immersion in the subject matter. The visual display at The Met was primed for all types of visitors to understand the relationships between time, place, culture, and artistic value. Once again, the spectator is a welcomed guest of the host institution.

Architectural models as “the sum of a culture”

Among the Eames Office’s talents were elaborate model-making and a tedious iterative process for solving an institution’s innate problems. During a question-and-answer session after a 1954 Eames lecture at the University of California, Berkeley, Ray addressed a crowd of students, adding her commentary to Charles’s lesson. “Things happen in making a model that never happen in any other way and never happen in the drawings or sketches,” she said. “In the making of a model you experience the third dimension.” Seeing the layers of reality in miniature first allowed the Eameses to envision spaces comprehensively, and it undoubtedly deepened the lived experience of their film screenings and exhibitions.

A section of the intricate model for a proposed national aquarium, 1967. © Eames Office, LLC. All rights reserved

Another monumental Eames Office architectural project was the design proposal for a national aquarium in 1967. A precursor to Metropolitan Overview, the commission involved a highly detailed model of the aquarium and a film to present it. Friend and scientist I. Bernard Cohen, after having seen the Eameses’ film, directed a taxi to the enticing National Fisheries Center and Aquarium. To his surprise, it didn’t exist. The convincingly life-like project was halted due to a lack of government funding, but its ideas were believable. Much like the aquarium model, The Met’s architectural sample was elaborate and reasonable enough to be made a reality. Hoving and his staff would bear witness to this thanks to the scenes and narration of Metropolitan Overview.

“In the end,” Charles said at the conclusion of a 1977 lecture, “models are what you hand on to the next generation. The ‘culture’ of a time is the sum of its models.” With this in mind, it’s easy to dream up the culture of The Met in 1975. One can also be curious about what elements of the proposal are relevant for The Metropolitan Museum of Art to adopt in the coming generations.

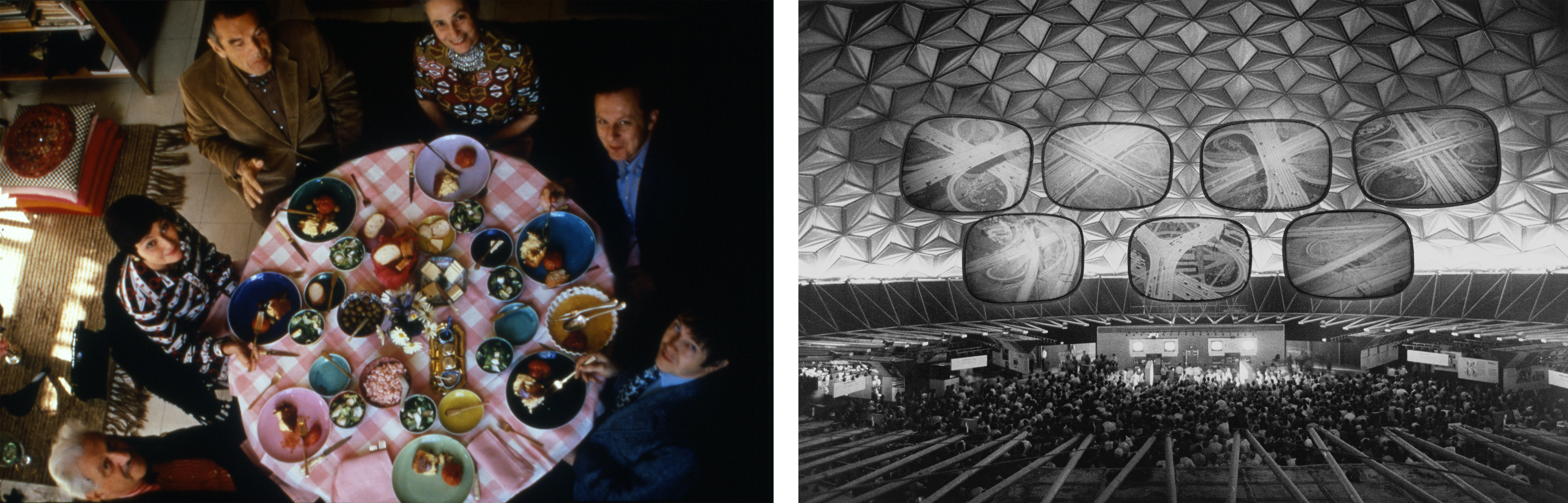

Researching for this proposal involved examining The Met in 1975 from all angles, whether physically or philosophically. © Eames Office, LLC. All rights reserved

Charles and Ray Eames collaborated tirelessly to build themselves into exhibition designers, message-bearers through film, art connoisseurs, teachers who distill complex information, and experts of comfort in public spaces. Above all, the Eames Office sculpted a people-centered approach to design. It’s felt most in the film’s punctuating sentences: “[The new Museum] can be a conclusion or an invitation—to help the visitor grasp what is here, to help him know his way about, and if need be, to remind him of his own footing in relation to the things themselves. To remind him: his own knowledge of life and of things, his own loves, his own curiosity… they’re all he needs to begin.”

To the Eameses, The Met's reconfigured floors and collaged displays would have been a wondrous envelope for a warm, technologically aided space for reorienting oneself around art. A design proposal of this scale can suggest the beginning of an enhanced museum, a refined city, and a better life.