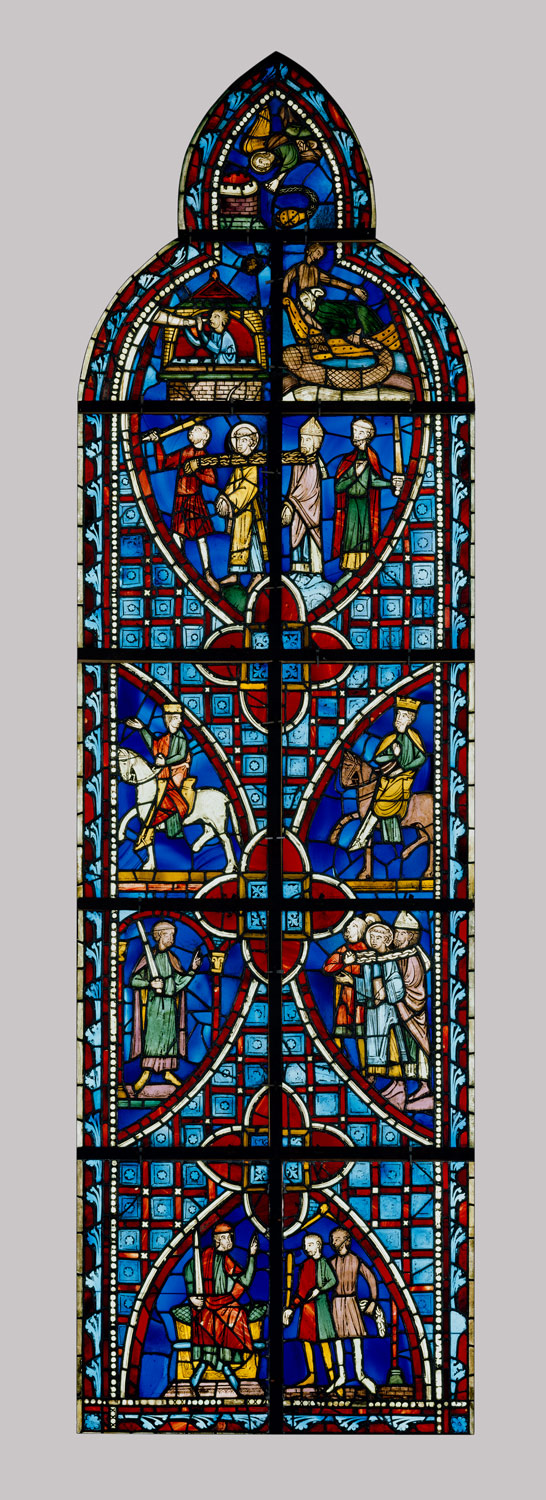

Between 1000 and 1400, the kingdoms of the Franks, divided among many leaders, become the kingdom of France, which emerges under the Capetian dynasty as one of the most prosperous, powerful, and prestigious in Christendom. Three kings stand out: Philip II (Philip Augustus, r. 1180–1223), Louis IX (Saint Louis, r. 1226–70), and Philip IV (Philip the Fair, r. 1285–1314). Each expands his political and territorial authority well beyond the capital at Paris, wresting lands from the English and attaching southern territories to his domain. Each establishes a centralized administration, a hierarchical judicial system, and an efficient system of taxation.

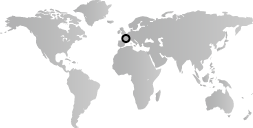

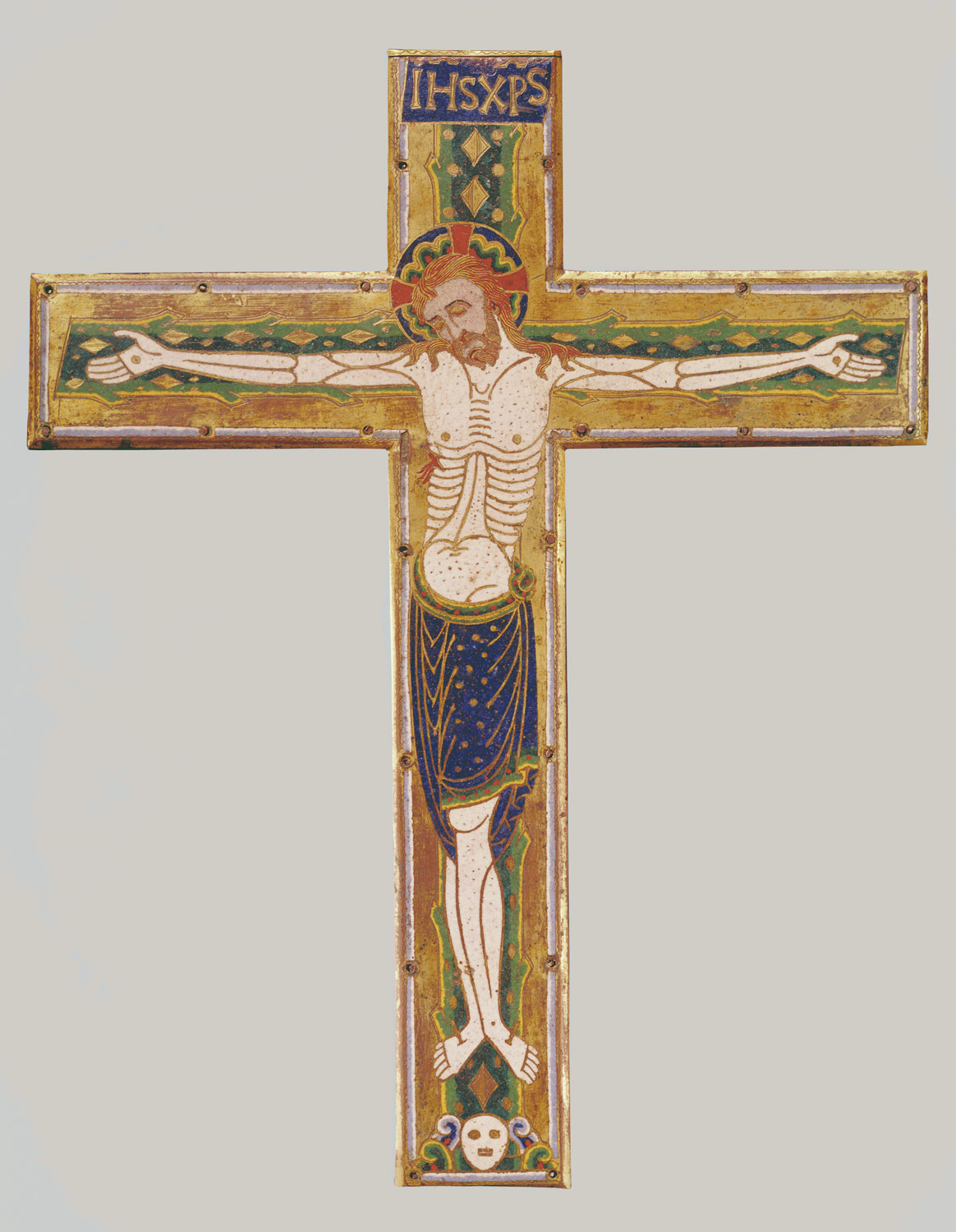

The Capetians earn much prestige on the religious front: they surround themselves with clerics as advisors and in return confer privileges and gifts on churches and abbeys. The most famous of these “ministers” is Abbot Suger of Saint-Denis, counselor to Louis VI and Louis VII, and regent during the Second Crusade until his death in 1151. Participation in the Crusades and pilgrimages, and, especially, the concept that the king’s authority derives from God (monarchie de droit divin), give the Capetians the title of “very Christian kings” (rois très chrétiens). The Crusades waged in the East, alongside constant battles with the English, generate a sense of French identity.

The expansion of royal authority is halted in the fourteenth century by an economic crisis, the loss of a third of the population to the plague, and, from 1337, constant military conflict with the English, who hold large territories in France. The fourteenth century also sees the establishment of the papacy in Avignon, under pontiffs who are natives of the Limousin region of central France.