In this period, Egypt confronts various internal and external threats. Artistic and architectural developments continue despite political and economic difficulties. Most important is the Portuguese domination of the Indian Ocean, which undermines Egypt’s pivotal role in world trade. When Mamluk rule is replaced with Ottoman rule and Egypt becomes a major province of a world empire, the arts in Cairo begin to reflect the imperial style set in Istanbul.

Egypt, 1400–1600 A.D.

Timeline

1400 A.D.

1450 A.D.

1450 A.D.

1500 A.D.

1500 A.D.

1550 A.D.

1550 A.D.

1600 A.D.

Overview

Key Events

-

1382–1517

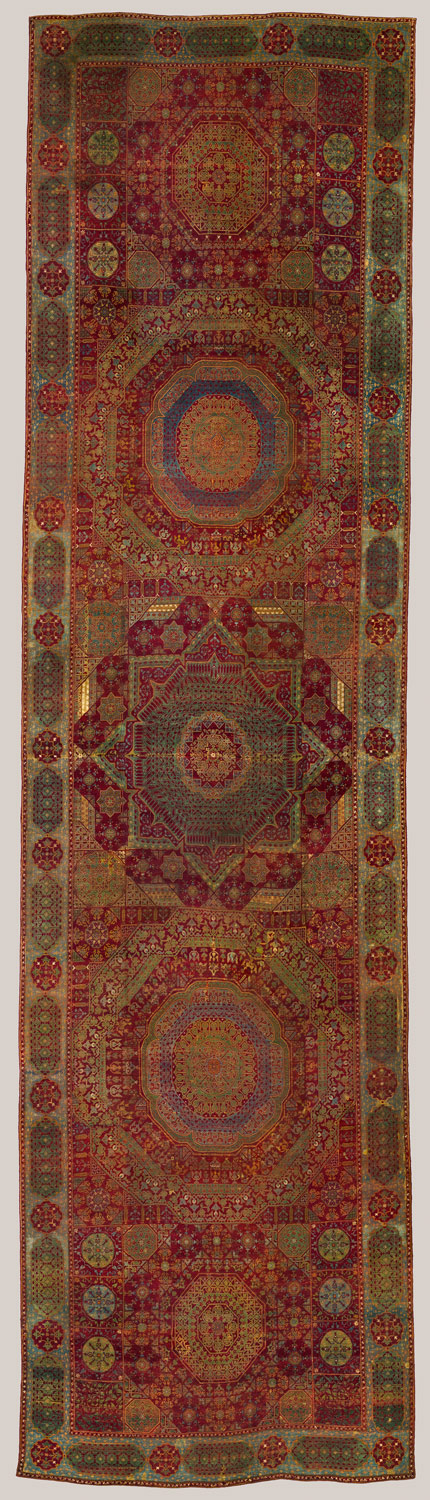

In the Mamluk sultanate, the Burji line of sultans, drawn from a military elite of professional slave soldiers of primarily Circassian origin, is in power. The Mamluk realm continues to benefit from the east-west trade in silks and spices. The arts, including enameled glass, inlaid metalwork, woodwork, and textiles, continue to flourish, and various religious and public monuments are built.

-

1400–1425

The Mamluk state suffers its greatest period of external and internal threats. Despite the devastation caused by the Central Asian conqueror Timur (Tamerlane; r. 1370–1405), as well as by famine, plague, and civil strife, arts and architecture continue to be produced. Mamluk architectural patronage focuses on public and pious foundations, which include commercial buildings, madrasas, mosques, and mausolea. Major architectural commissions from this period include the public and pious foundations by Faraj (r. 1399–1412), Mu’ayyad Shaikh (r. 1412–21), and Barsbay (r. 1422–37).

-

1468–1496

Reign of Qaitbay, the greatest of later Mamluk sultans. During his rule, Cairo and Alexandria are endowed with commercial buildings, bridges, canals, and religious foundations. Although the Mamluk realm is frequently at war with the Ottomans of Anatolia, architectural patronage continues. Qaitbay’s funerary complex in the Northern Cemetery is the most celebrated structure of this period (1472–74). Others include the madrasas at Qal‘at al-Kabsh (1475–76) and on Roda Island (1481–90), two caravanserais (1477–79), a water dispensary, and a Qur’an school (1479).

-

1498

Following Vasco da Gama’s voyage to India via the Cape of Good Hope, the Portuguese gain control of the Indian Ocean and bar Mamluks from the spice trade, their richest source of revenue. Egypt’s pivotal role in the east-west trade is weakened.

-

1501–1517

Under the last Mamluk sultan, Qansuh al-Ghawri, arts and architecture follow the style of Qaitbay. The critical financial situation of the sultanate is reflected in the construction methods of the period. The most important commission at this time is the funerary complex of the sultan, which includes a mosque, madrasa, mausoleum, convent, Qur’an school, and water dispensary and is supported by a caravanserai and commercial hotel (1503–5).

-

1516–1517

Ottoman armies under Selim (“the Grim,” r. 1512–20) conquer Syria and Egypt, bringing an end to the Mamluk sultanate.

-

1517–1805

Under Ottoman rule, Egypt is no longer the center of an independent state, but is an important regional center. Initially, the arts and architecture continue the styles set by the Mamluks. The Ottomans greatly admire the works of their predecessors and do not immediately impose the style set in Istanbul. However, with time, imperial Ottoman elements are integrated into the local vocabulary. Textiles and carpets are recognized in the international market. Along with Istanbul and Baghdad, Cairo is an important center for the arts of the book.

-

1520–1566

Often regarded as a “Golden Age,” the reign of Süleyman, popularly known as “the Magnificent” or “the Lawmaker,” is defined by geographic expansion, trade, economic growth, and tremendous cultural and artistic activity. During this period, Ottoman officials appointed to Cairo, the capital of the Ottoman province of Egypt, commission public and pious foundations. Noteworthy are the mosque and madrasa of Süleyman Pasha (1528, 1543) as well as the fountain of Khusraw Pasha (1535).

-

1571

Sinan Pasha commissions a mosque on the banks of the Nile that is inspired by an example from Istanbul.

-

1597

Work begins on the mosque of Safiye, wife of Murad III (r. 1574–95). Apart from being one of the few sixteenth-century monuments in Egypt with distinctly Ottoman imperial features, the mosque is also significant as an example of female patronage in an Ottoman provincial center.

Citation

“Egypt, 1400–1600 A.D.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/ht/?period=08®ion=afe (October 2002)