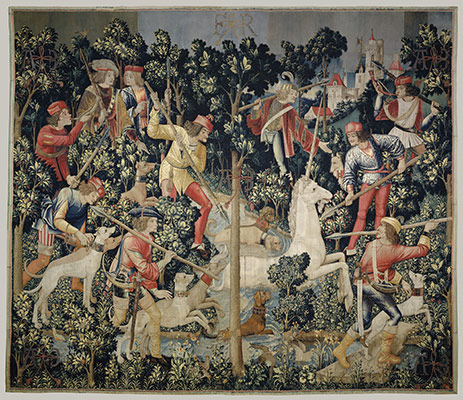

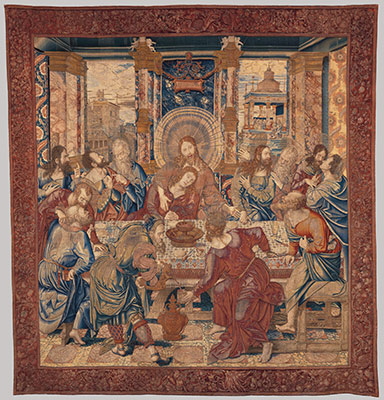

The greater part of this period is marked by economic prosperity, the growth of cities, and prodigious artistic innovation in the Low Countries. The dukes of Burgundy, who rule there until 1477, are great patrons of the arts; foremost among them is Philip the Good (r. 1419–67), who around 1420 moves his court from Dijon to Lille and then Bruges. Up to this time, metalwork, illuminated manuscripts, and tapestries dominate as the most highly prized art forms, but the early fifteenth century witnesses the emergence of a new art form that is quickly recognized as one of the most remarkable achievements of the period: panel painting. Founded by Robert Campin (1378/79–1444), Jan van Eyck (1390/1400–1441), and Rogier van der Weyden (ca. 1399–1464), Netherlandish painting is praised throughout Europe for its keen observation of detail and its enamel-like surface achieved by built-up layers, or glazes, of oil paint.

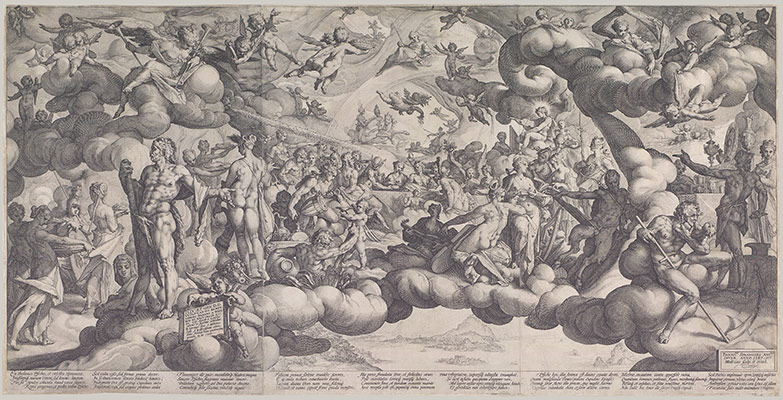

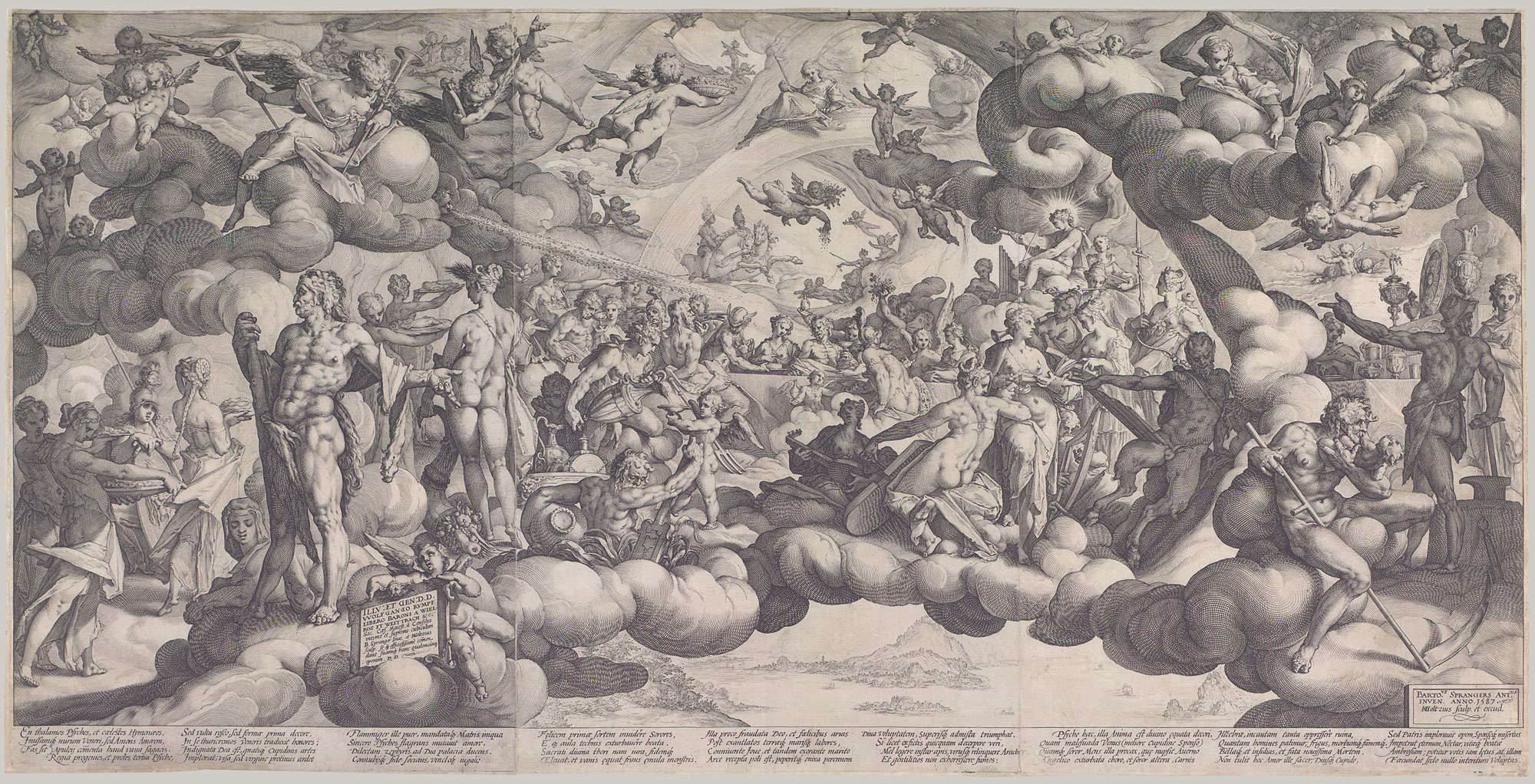

Arts in all media flourish: while the church is still a key patron, members of the affluent middle class and prosperous corporate bodies commission tapestries and stained glass, often designed by painters, as well as metalwork, sculpture, and furniture. Printmaking becomes an important art form after 1500; among its greatest practitioners are Lucas van Leyden (1489/94–1533), Maarten van Heemskerck (1498–1574), and Hendrick Goltzius (1558–1617). In the latter years of the sixteenth century, however, countless works of art are destroyed as the Low Countries engage in a series of bloody conflicts with Spanish Habsburg rulers. In 1581, the northern provinces become an independent state, known as the States General or the Dutch Republic.