During this period, central Europe is a seat of religious upheaval, intellectual activity, and technical innovation. Holy Roman Emperors struggle with increasing difficulty to control their territorial holdings—the boundaries of which continue to expand until the late sixteenth century—in the face of opposition from local princes and foreign threats, especially France and the Ottoman Turks. By the sixteenth century, humanist ideas from Italy—chiefly a renewed interest in classical scholarship—take root in central Europe, where they are promoted at centers of learning such as the University of Wittenberg, founded in 1505. It is here that professor of theology Martin Luther sets in motion the events leading to the Protestant Reformation, rejecting the authority of a corrupt clergy and asserting that of the Scriptures themselves.

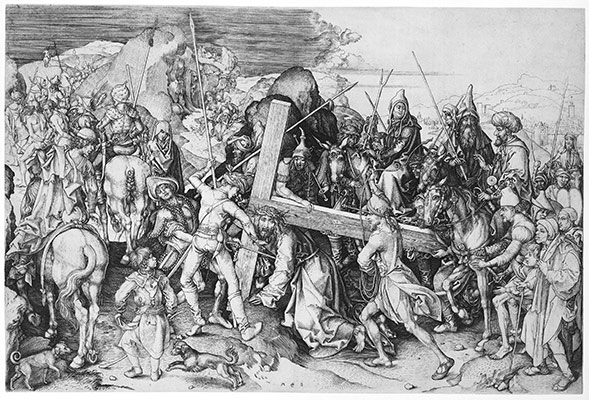

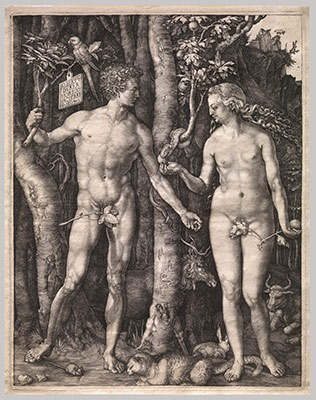

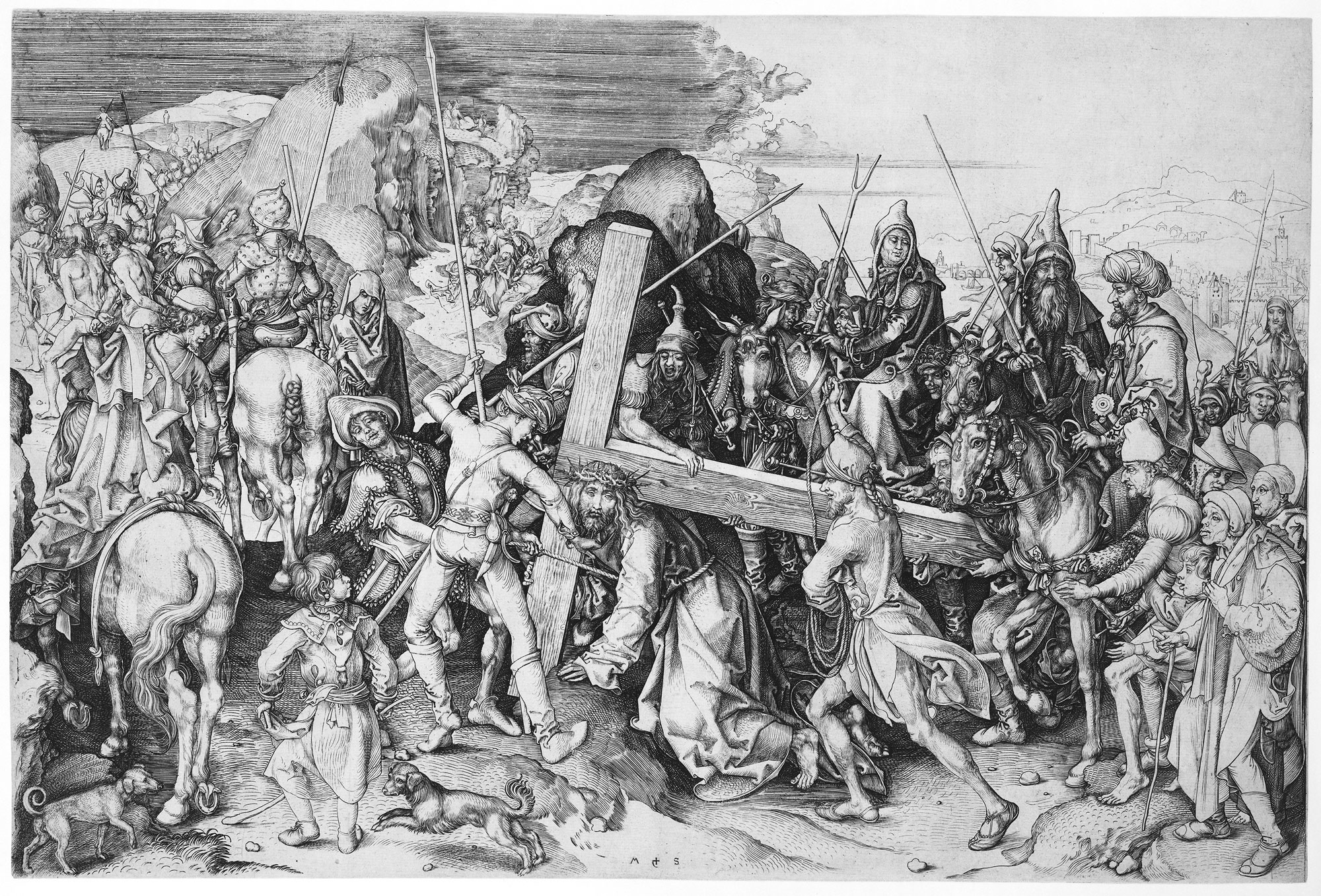

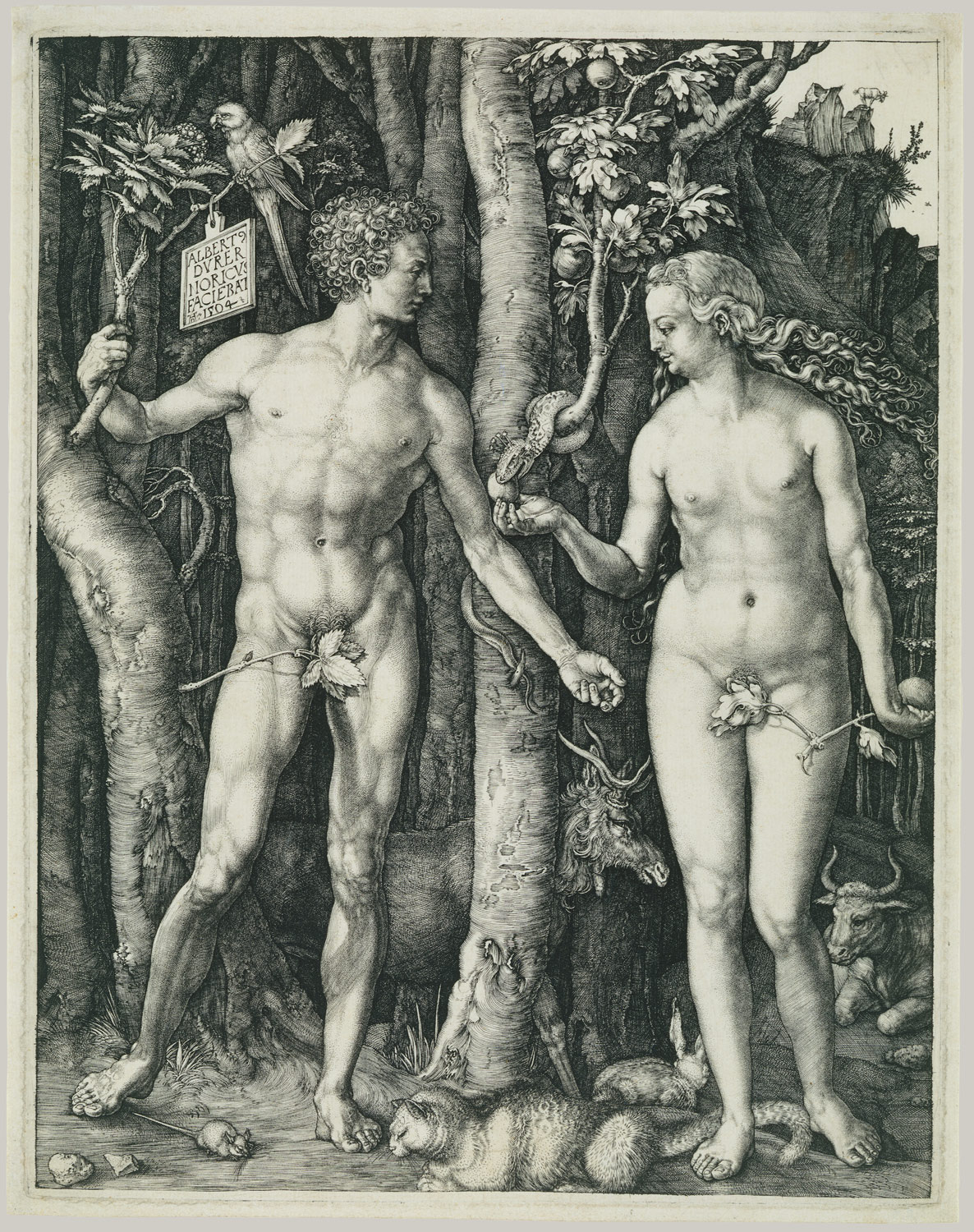

Of great importance is the rise of printmaking in the fifteenth century, of which the works of Martin Schongauer (1445–1491) and Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) are the crowning achievements. An unprecedented demand for sculpture in all materials leads to radical innovations in southern Germany. Easel painting flourishes throughout the period; the iconoclastic movement that accompanies the Reformation is a significant setback for religious painting, whereas secular subject matter rises in popularity.