Book of the Gospels

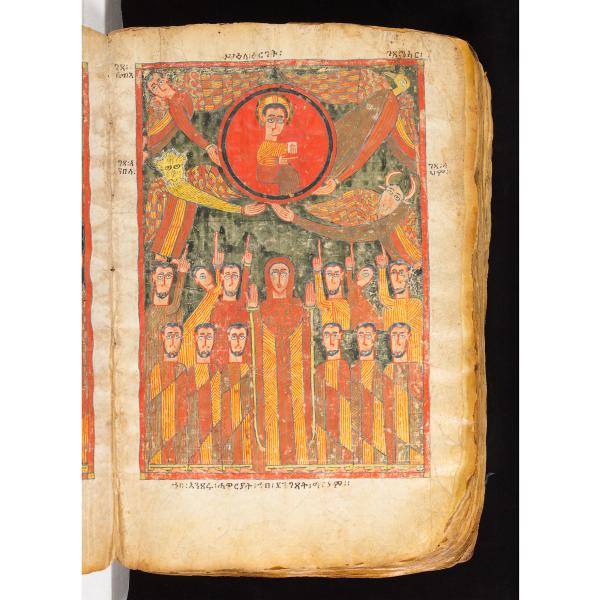

This work is evidence of sub-Saharan Africa's historically complex interrelationships with Arabia, Egypt, and the eastern Mediterranean. Early complex societies in the Highlands developed primarily through local processes beginning in the late second millennium B.C.E. Those societies attracted trade from across the Red Sea, Mediterranean, and Indian Ocean, which spurred migrations, religious exchanges, and greater concentrations of wealth. By the early first millennium C.E., the Kingdom of Aksum emerged as a powerful civilization that, at its height, extended from Ethiopia's Highlands in the South, to the Eastern Desert in the North, to southern Arabia in the East. Emperor Ezana (r. ca. 320s-360 C.E.) was the first monarch to convert to Christianity, and adopted it as the state religion. Subsequent kingdoms, including the Zagwe Dynasty (ca. 1137-1270 C.E.) and the Ethiopian Empire (1270-1974 C.E.) continued to embrace Christianity. Monasteries were founded as centers of learning responsible for disseminating knowledge and consolidating the power and influence of the ruling elite. In the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, the text of the Gospels was considered the most important holy writing; the miniatures at the beginning of this manuscript were intended to be viewed during liturgical processions. Such works were frequently presented to churches by distinguished patrons; they reflected both the prestige of royal benefactors and the erudition of the monastic scriptoria in which they were created. Recent research suggests that a member of Ethiopia's ruling elite may have commissioned this manuscript at Dabra Hayg Estifanos monastery for presentation to his or her favored church or monastery. Brief notations indicate that the church in question was dedicated to the Archangel Michael.

Artwork Details

- Title: Book of the Gospels

- Artist: Northern Highlands artist

- Date: late 14th–early 15th century

- Geography: Ethiopia, Lake Tana region

- Medium: Parchment (vellum), acacia wood, tempera, ink

- Dimensions: H. 16 1/2 x W. 11 1/4 x D. 4 in. (41.9 x 28.6 x 10.2 cm)

- Classification: Hide-Documents

- Credit Line: Rogers Fund, 1998

- Object Number: 1998.66

- Curatorial Department: The Michael C. Rockefeller Wing

Audio

1525. Book of the Gospels, Northern Highlands artists

Maaza Mengiste

MAAZA MENGISTE: When I see this book, what I see is a centuries-old relationship between the written word and religion. These religious texts were the primary expression of writers in Ethiopia until more modern times.

My name is Maaza Mengiste. I was born in Ethiopia, and I am an Ethiopian/American writer.

Ethiopia has had a deep history of literature, of writings. It has been steeped in the written word as a way to preserve the memories of different empires, of different rulers.

ANGELIQUE KIDJO (NARRATOR): In the sixth century, Ethiopians started translating the gospel into Geʽez—one of the oldest written languages in the world, and which remain the language of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church.

MAAZA MENGISTE: This has been the way that religion was passed down. Priests could read this and could then provide interpretations of the Bible to their congregations. Writing in Ethiopia has been deeply, intricately connected with its religions, whether it's Arabic or whether it’s Geʽez or Amharic.

ANGELIQUE KIDJO: The tradition of illuminating, or artistically rendering the people and narratives from a religious text, also points to something beyond words.

MAAZA MENGISTE: When I see the drawings next to the writings, it tells me that there is another layer that’s happening here. These drawings are seeking to affirm something that is outside of language. It’s a connection that has no real words, and I think that the intricateness of these drawings, the richness of the colors, the golds, the reds, they are, in a sense, trying to reflect visually what it might mean to have an epiphany.

Listen to more about this artwork

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.