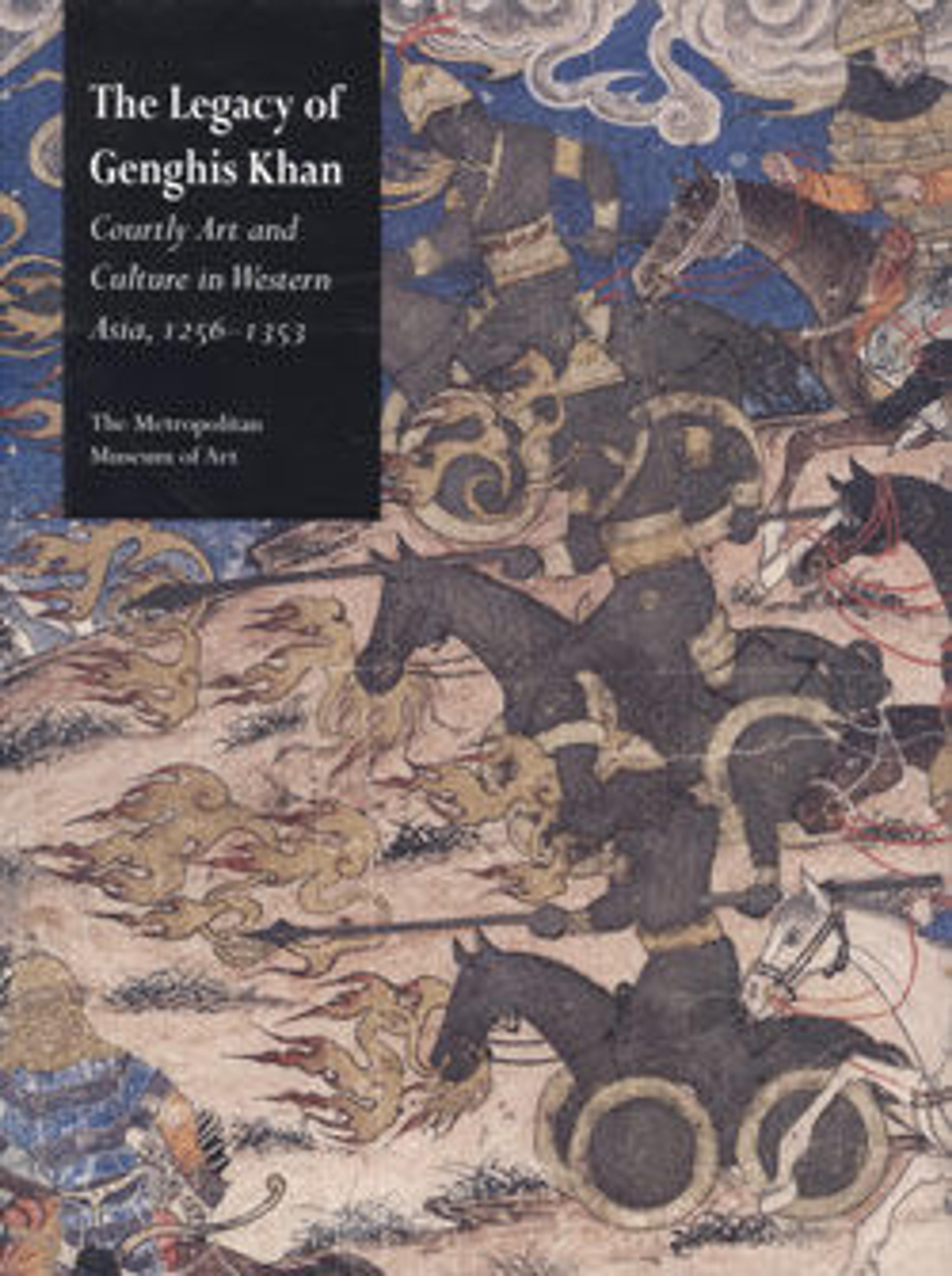

"Nushirvan Eating Food Brought by the Sons of Mahbud", Folio from a Shahnama (Book of Kings)

This page once formed part of a now-dispersed manuscript known as the Great Mongol Shahnama, believed to have been produced in the 1330s at Tabriz. A large-scale work, it would have once contained nearly 300 folios with almost 200 paintings. The subject of this beautifully painted folio is unclear as its imagery does not relate directly to its surrounding text, but it likely represents the king Nushirvan dining.

Artwork Details

- Title: "Nushirvan Eating Food Brought by the Sons of Mahbud", Folio from a Shahnama (Book of Kings)

- Author: Abu'l Qasim Firdausi (Iranian, Paj ca. 940/41–1020 Tus)

- Date: 1330s

- Geography: Attributed to Iran, Tabriz

- Medium: Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper

- Dimensions: Page: H. 20 3/4 in. (52.7 cm)

W. 15 1/8 in. (38.4 cm)

Painting: H. 8 1/8 in. (20.6 cm)

W. 9 1/8 in. (23.2 cm)

Mat: H. 22 in. (55.9 cm)

W. 16 in. (40.6 cm) - Classification: Codices

- Credit Line: Purchase, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, 1952

- Object Number: 52.20.2

- Curatorial Department: Islamic Art

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.