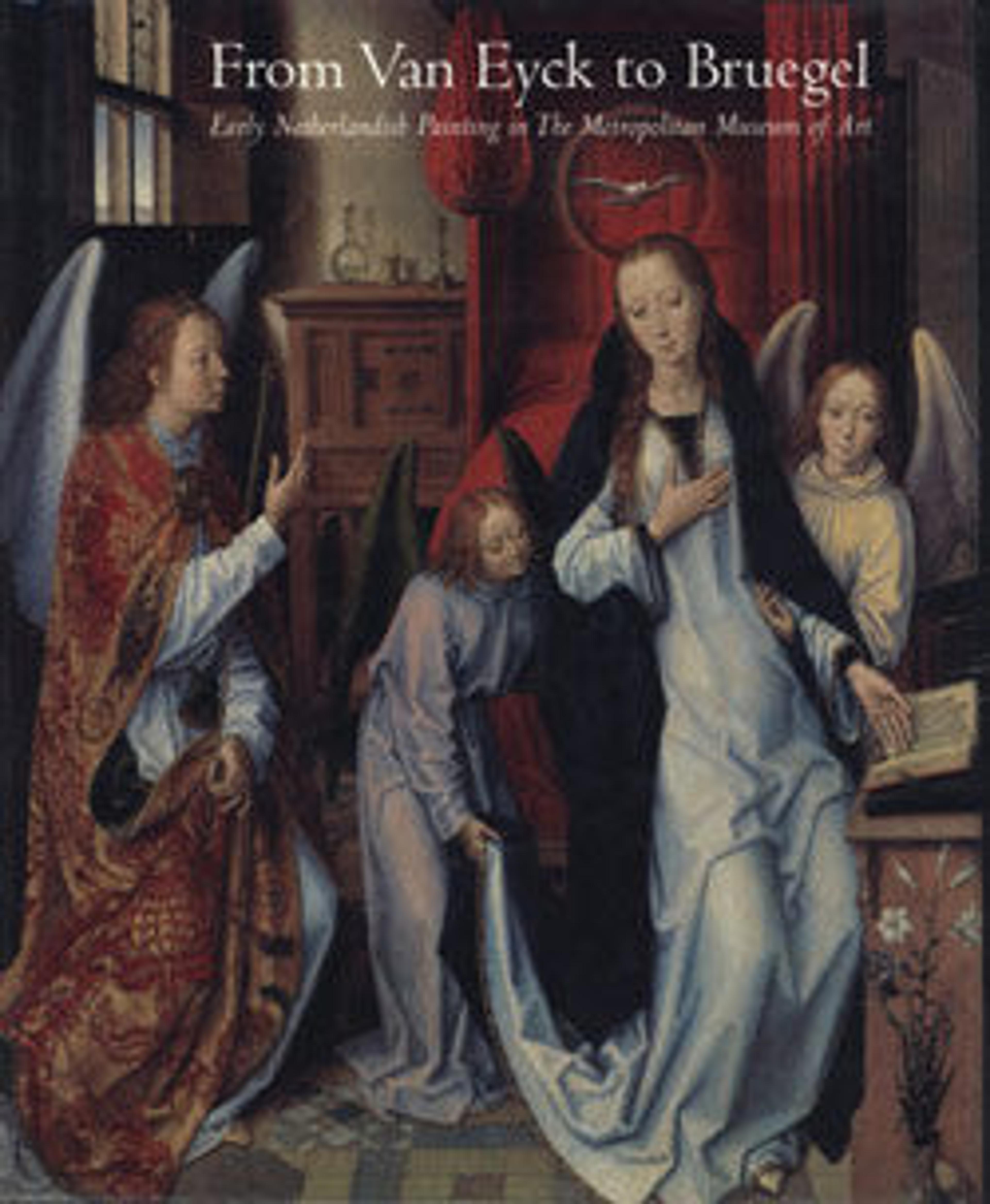

The Adoration of the Magi

This painting is a very rare surviving example of distemper, a water-based medium, on canvas. The artist was active both in his native Ghent, in modern Belgium, and at the refined court of Urbino in Italy. Three Black figures in the composition—the African king, the servant handing him his gift, and an observer in the crowd—reflect the increasing presence of Black individuals in western Europe, but their strikingly similar appearance raises the question of whether they derive from a single model or were based on an idealized type.

Artwork Details

- Title: The Adoration of the Magi

- Artist: Joos van Wassenhove (Netherlandish, active by 1460–died ca. 1480)

- Date: 1472–74

- Medium: Distemper on canvas

- Dimensions: 43 x 63 in. (109.2 x 160 cm)

- Classification: Paintings

- Credit Line: Bequest of George Blumenthal, 1941

- Object Number: 41.190.21

- Curatorial Department: European Paintings

Audio

2618. The Adoration of the Magi

0:00

0:00

We're sorry, the transcript for this audio track is not available at this time. Please email info@metmuseum.org to request a transcript for this track.

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.