The Marriage Contract

Jean-Baptiste Greuze French

Not on view

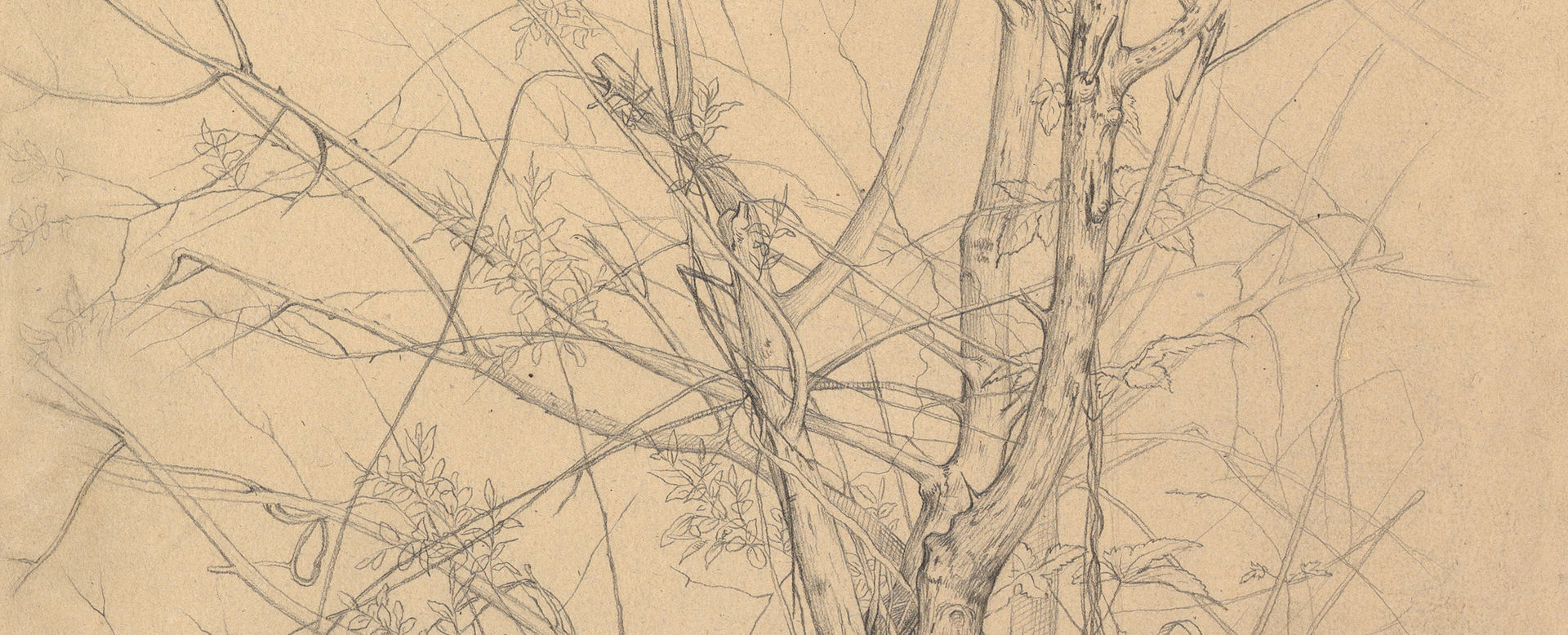

This colored compositional study is Greuze’s première pensée, or initial idea, for his famous painting, The Marriage Contract (L’Accordée de village), today in the Musée du Louvre, Paris. The painting, which depicts the signing of a marriage contract in a rural household, was commissioned by the marquis de Marigny (1727–81), the powerful director of the king’s buildings (Directeur des Bâtiments du Roi), from a young artist who was considered a rising star. After arriving three weeks late for the Salon of 1761, Greuze’s picture became one of the most discussed works on view. Denis Diderot was among the many critics who penned long appreciations exploring the psychological and social nuances of the family drama.

The fame of the picture added to the desirability of the studies, and this sketch found a prominent home in the collection of Jean de Jullienne (1686–1766), the pioneering collector and promoter of the French school. The taste for colored sketches, in oil or gouache, was widespread among connoisseurs of the period, who considered their freedom and broad handling to reveal the genius or ‘fire’ of an artist. Jullienne's admiration for Greuze's study is evident in the fact that he kept it not in a portfolio but framed under glass.

Greuze’s innovation was to treat everyday subjects (called genre scenes) with the scale and gravity of subjects drawn from ancient history. In a working process that paralleled that of a history painter, he prepared his major genre scenes with a great number of studies – of compositions, figures and heads. At the beginning of the process was the première pensée, which represented the artist’s initial flash of inspiration, where the kernel of his idea first took form. Next, the artist executed more detailed studies of individual figures and heads. In the case of The Marriage Contract, once he had established the poses and expressions of each of the major figures in the composition, Greuze made a second compositional study (Musée du Petit Palais, Paris), presumably as a modello to present to his patron, the marquis de Marigny.

Situated at the beginning of the creative process, the Met’s sketch is perhaps best described as a hybrid object, begun as a drawing and finished as a colored sketch. The urgency of its creation is embodied in its fluid handling, as seen in its looping swirls of brushwork and animated dabbing and blending of color. Greuze began by laying down his first thoughts for the composition very broadly in red chalk, most clearly seen in the pentimenti: the head of the bridegroom was initially conceived as tilted to the left, towards the bride; the father’s right hand was higher; and the entire structure of the end of the wall and the diagonal stair banister was first positioned several inches to the right. He then used a brush with dark grey wash to articulate the figures and their clothing. In some areas (the bride’s bodice) he used the fine-tipped point of the brush, while in others (the hanging coat of the notary) he applied a broader line. His fluid, almost calligraphic, handling of wash is characteristic of his draftsmanship for compositional studies early in the design process. What is unusual was his decision to work up the composition using a mixture of gouache and watercolor washes. Opaque in some areas and translucent in others, these colored washes allowed the artist to explore the overall color scheme and the details of each figure’s dress and to articulate the facial expressions.

Beyond the addition of two figures (a female servant at left and a male figure ascending the stairs), there are many changes between the première pensée and the final canvas, which can be grouped into categories. Some were apparently the result of formal considerations, most notable of which is the extension of the wall behind the family group. Thus, the column, which in the sketch aligns with the bride’s head, is shifted in the painting so that she is seen against a less distracting backdrop. Similarly, the position of the seated notary was rotated inwards and away from the viewer, reinforcing the diagonal movement from lower right to the apex of the figural grouping. This pyramidal structure, borrowed from the conventions of history painting, is visually reinforced by the diagonal line of the banister at left and by the shadow on the wall at right.

Other changes were made in order to reveal the emotional states of the characters. The most important of these was the rethinking of the father’s gestures. Instead of grasping the bridegroom’s arm with his right hand, in the painting his hand is at the very center of the canvas, palm towards the viewer, in a rhetorical gesture, as if to make the point to the young man, and more importantly, to the painting’s audience, that the real treasure is not the dowry in the clutched bag, but his virtuous daughter. The gestures and expression of the bride were also refined by Greuze to enhance our perception of both her physical allure and her appealing modesty. Her posture, straight in the sketch, in the painting takes on a slight S-shaped curve to accommodate on her shoulder the resting head of her weepy younger sister as well as the outward bend of her arm which she lightly slips around the arm of her betrothed, her fingertips only grazing his hand, expressing a restrained tenderness that was much praised by contemporary critics. Further accentuating the demure character of the bride in the painting are her downward cast eyes. In the sketch, her gaze is clearly directed to her left, at the transaction between men that governs her future.

Changes in the color of certain areas also serve to reinforce the psychological characterizations of the figures. While the sketch’s overall palette of pastels blended with grays is retained in the painting, many individual elements have changed: the mother’s dress has gone from blue to brick-hued, the bridegroom’s breeches from blue to mauve. Most significant, however, is the change in the bride’s dress, which in the panting is given a filmy whiteness, a paleness which sets her off from the more saturated colors of the other figures, accentuating her purity.

(Perrin Stein, July 2017, extracted from Burlington Magazine, March 2013, pp.162-66)

Due to rights restrictions, this image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.