Red, black, and white chalk are naturally occurring minerals mined from the earth. Easy to use, they require no special preparation or complicated tools, and are suited to making both preparatory and highly finished drawings. Soft and compact, these materials can be sawed into narrow sticks or broken into small pieces. Artists often place chalk into holders to keep their hands clean and protect drawings from smudging.

Clockwise from top center: lumps of red chalk, bread crumbs, gum eraser, stumps, porte-crayons (chalk holders), fabricated chalks, white chalk, red chalk wash, black chalk (at center)

Inherently cohesive, yet powdery, chalk of all colors readily adheres to paper and produces marks with little pressure and minimal crumbling. When the chalk is dense and hard, it can make narrow lines and precise images. It can be used for simple compositions of parallel and crossed hatches, or worked using broad, overlapping, painterly marks. Michelangelo's drawing below demonstrates the medium's ability to describe both line and tone.

Michelangelo Buonarotti (Italian, 1475-1564). Studies for the Libyan Sibyl (recto) (detail), ca. 1510-11. Red chalk, with small accents of white chalk on the left shoulder of the figure in the main study (recto), 11 3/8 x 8 1/2 in. (28.9 x 21.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, 1924 (24.197.2)

Stumping is a technique in which artists use coils of paper (known as stumps), pieces of leather, or a finger to spread the chalk. This process produces diffuse, light areas in a drawing.

Combining powder scraped from a chalk stick with water produces a wash that, when applied with a brush, results in a semi-transparent effect.

Mattia Preti (Il Cavalier Calabrese) (Italian, 1613-1699). A Group of Saints and Angels (recto) (detail), 1613-99. Red chalk, brush and red wash, 6 x 7 1/8 in. (15.1 x 18.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1970 (1970.113.6)

Red chalk is an iron-oxide pigment that contains clay and other mineral compounds. It was highly regarded as a drawing material from the fifteenth through the eighteenth centuries, when it was attractive to draftsmen for the quality of its color and broad range of effects. Different trace elements in the mineral account for a variety of related colors that range from crimson to orangey red. Historically, artists purchased natural chalk in various hues from color merchants, sourced from quarries across the globe.

Antoine Watteau (French, 1684–1721). Standing Woman Holding a Spindle, and Head of a Woman in Profile to Right (detail), ca. 1714–18. Two shades of red chalk, 6 1/2 x 4 7/8 in. (16.4 x 12.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequeathed be Anne D. Thomson, 1923 (23.280.5)

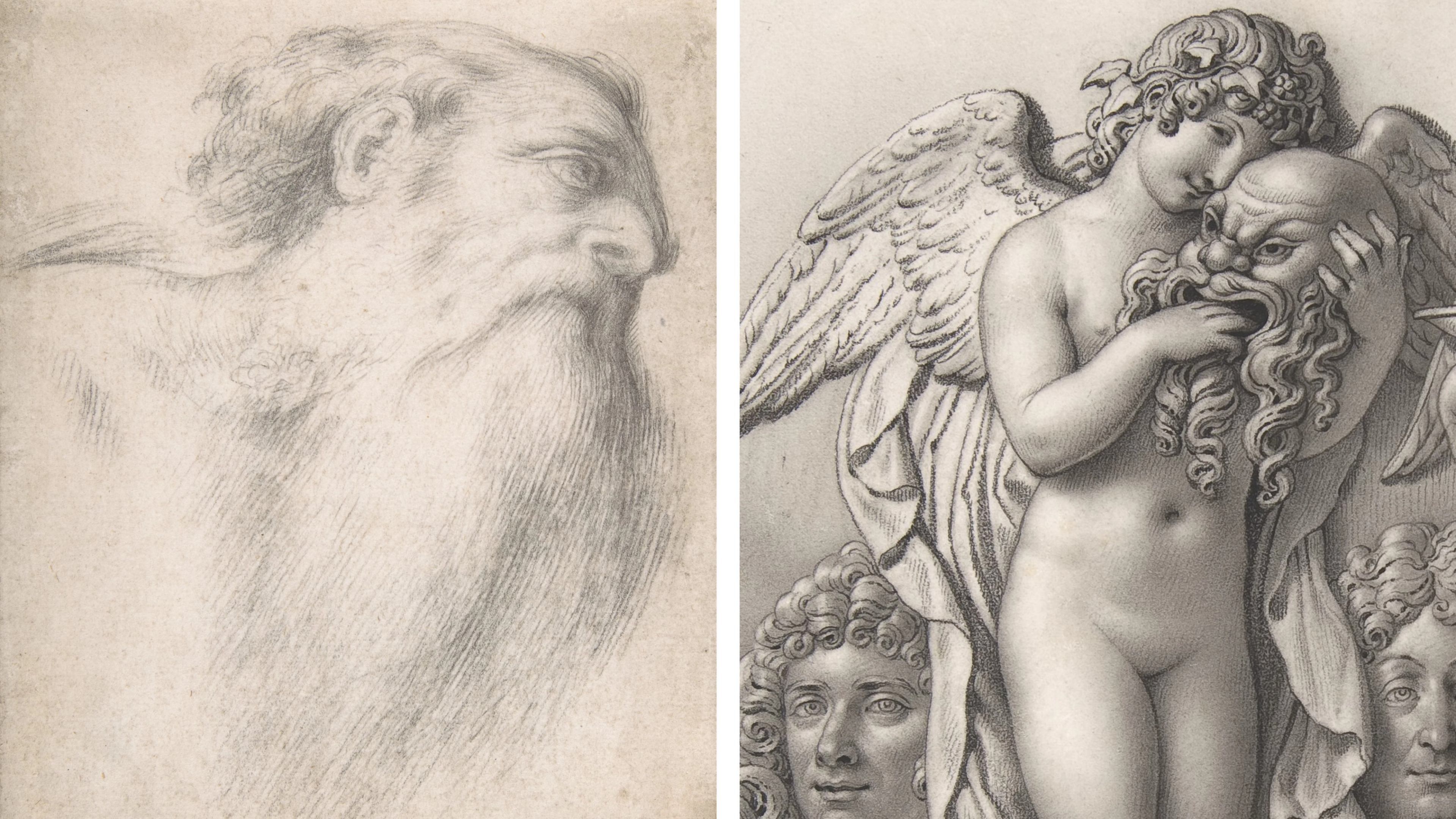

Black chalk is made from shale or schist, minerals that contain carbon. It is capable of producing varying shades of black. Chalk suited to drawing is both homogenous in texture and relatively soft and yielding. Popular as a medium since the Renaissance, its uses range from preparatory drawings to highly finished compositions.

Left: Lorenzo Lotto (Italian, ca. 1480–1556). Head of a Bearded Man (detail), 1516–17. Black chalk on paper, 6 5/8 x 5 1/4 in. (16.9 x 13.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Florence B. Seldon Bequest, 1996 (1996.413). Right: Anne Louis Girodet-Trioson (French, 1766–1824). Comedy and Tragedy (detail), 1814. Black chalk and stumping, 9 1/4 x 12 1/2 in. (23.5 x 31.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Karen B. Cohen Fund, 2003 (2003.5)

In a technique referred to as "heightening," draftsmen enhanced their work with touches of white chalk. Employed since antiquity, white chalk is made of the mineral calcite, a type of limestone formed from shells beneath the seabed. This medium is especially effective when applied to toned or colored sheets of paper.

The combination of two or three colors of chalk, a technique known by the French terms deux or trois crayons, was particularly popular in the eighteenth century.

Jean-Baptiste Lemoyne the Younger (French, 1704–1778). Portrait of Étienne Maurice Falconet (1716-1791) (detail), 1741. Black, red, and white chalk, with stumping, 16 3/4 x 13 1/2 in. (42.6 x 34.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, The Morris and Alma Schapiro Fund Gift, 2012 (2012.415)

Powdered and mixed with water or gum size, red chalk was also used to create brilliant colored grounds.

Wolfgang Huber (German, ca. 1485/90–1553). Bust of a Man (detail), 1522. Black and white chalk on red prepared paper, 11 5/8 x 7 7/8 in. (29.4 × 20 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1950 (50.202)

Drawing with chalk can be particularly challenging as it requires careful attention to avoid smudging. Making corrections is difficult, as well: once chalk is embedded between the fibers of paper, its fine particles are difficult to remove. For this reason, it was an ideal tool for the disciplined instruction of drawing in eighteenth-century academies. In the past, artists rubbed off unwanted chalk with breadcrumbs or scraped it off with pumice, or a penknife. Today's artists can use these tools and various types of rubber erasers.

Fabricated red and black chalks have now replaced the pure, raw forms: mined supplies grew scarce and manufactured sticks offered consistency of color and texture. White chalk remains naturally abundant and is fabricated, as well.

See a selection of chalk drawings in The Met collection.