In January 2024, The Metropolitan Museum of Art began exhibiting a large collection of Early Cycladic marble figures, which joined a smaller group already on display in the Belfer Court in the Greek and Roman Galleries. Lovely in form and mysterious in meaning, these works are perhaps most compelling as windows into a world populated by people living in an archipelago of small islands scattered between the Peloponnese and the coast of Turkey some 4,000 to 5,000 years ago. It was a time before language had been squeezed into a system of durable writing, when individuals expressed stories and identities in the form of oral history and art. Works made of stone and clay may have survived, but countless other forms of expression, such as dance, storytelling, music, and religious practices, remain locked mysteries. It is critical to remember that archaeological evidence is just a tiny fraction of past cultures and their creative expressions. The Cycladic figures we quietly observe in glass cases were not experienced that way by their makers. Rather, they were part of the indigenous life of some of the Cycladic islanders, likely active in the dramas of their days, possibly even dressed, helping to connect individuals to their communities present, past, and future.[1]

View of gallery 151 showing Cycladic marble figures from the Leonard N. Stern Collection

One of the most tantalizing features of these marble figures is the painted motifs applied to their surfaces many millennia ago. Dramatically expressive eyes, impressive coiffures, and mystifying markings on various body parts were painted with at least two different colors. One is a vibrant blue pigment made of azurite, and the other is a dense, rich red pigment made of cinnabar or, less often, hematite. Azurite has been found packed into small clay and bone vessels deposited as grave goods.[2] Cinnabar has been identified on the surface of shallow marble bowls and some of the marble figures. It is likely that other colors were used as well, as will be argued below.

Since the late nineteenth century, scholars have documented painted designs and representational motifs on figure types of the Early Cycladic periods—the early violin-shaped figures, the Kapsala and Spedos figures that make up the largest group, and the angular and abstract forms of the Dokathismata and Chalandriani varieties.[3] The Leonard N. Stern collection, which I first studied in 1992, represents all of these styles. I revisited the collection in May and December of 2023 and found clear evidence of paint on thirty of the ninety-five figures and figure fragments, with another twenty-four figures exhibiting possible evidence of pigment.

There are several ways that one can discern evidence for ancient painting. Translucent pigments, such as azurite, need to be left fairly coarse to retain their color—the finer they are ground, the paler they become due to increased light refraction. As a result, such chunky pigments need to be mixed with a viscous medium such as wax or tree resin so that they readily adhere to the marble in a layer thick enough for the color to stand out. This sort of medium would have formed a barrier to water and its corrosive constituents over very long periods, thereby protecting the stone where the paint was applied. The effects, known as paint ghosts, can be seen today as areas that are now raised (in the most extreme examples) or areas with a slightly different sheen to the marble relative to the unpainted areas. For this reason, I have chosen to indicate paint ghosts as blue on the color reconstructions.

Other pigments, like cinnabar, may have been applied more sparingly due to their physical opacity. Such pigments could be very finely ground and still be readily visible against the white stone. In these cases, a thin oil, glair (whipped and rested egg white), or another very fluid medium could be used. The tiny particles of such pigments might lodge in the interstices of the marble crystals during the weathering process, thereby remaining on the stone and identifiable millennia later. [4] Pigments also may have been suspended in a medium that itself had a corrosive effect on the stone or that attracted soil, thus inviting bacteria or other creatures to feast on the medium and secrete substances that partially dissolved the stone where the paint had been applied. Such processes may explain the “pitting” or roughened pattern that appears on the stone in shapes that seem to correspond to ancient painted motifs and may suggest a third color—possibly brown earth used for certain motifs. Unfortunately, hundreds of centuries of deposition erased traces of medium in quantities sufficient to be detected by instruments available today, so the vehicles that carried the pigment and adhered it to the stone can only be conjectured by their effects on the stone. Particles of red pigment that remain can be seen with magnification or the unaided eye, and have permitted me to complete the patterns they suggest on the color reconstructions. I have used brown in the color reconstructions to indicate motifs that appear as pitted patterns

It is valuable to consider how these colors would have been prepared and applied to the stone surface. After pigments were collected, cleaned, and ground, the chosen medium needed to be obtained and refined. If wax was used, for example, it needed to be heated to flow as paint. Perhaps paintbrushes were made from hair, frazzled twigs, quills, feathers, or even bronze awls or needles.[5] Many of the painted designs on these marble figures are impressively precise and controlled: painters were highly skilled at choosing their source of pigments, mixing them with the appropriate medium, and fashioning and using their tools.

Azurite and cinnabar, both striking colors, are also associated with other materials, in particular metals. For example, the dazzling blue of azurite signals the presence of copper ore. There is evidence of copper mining and processing in the western Cyclades during the Early Bronze Age,[6] and copper was being smelted on the island of Kea (where many marble figures have been excavated)[7] and turned into tools, adornments, and other objects since the end of the Neolithic period.[8] One can imagine a bright blue rock winking at a curious and receptive passer-by who takes up the challenge, informed perhaps by stories of skilled neighbors, and sees what can be done with it. After being crushed, mixed with charcoal, and heated to a very high temperature by forcing air across coals with a blowpipe, this bright blue rock would yield a puddle of molten copper that could then be remelted and cast into shapes or hammered into sheets. Significantly, people brought modest quantities of ores to the fuel-poor island of Keros for small-scale smelting operations near the settlement at Kavos. This effort, and its yield, in the words of its modern investigators, “would have made smelting a socially highly-charged process.” [9] This blue is truly a magical substance.

Cinnabar is mercuric sulfide, the deep red ore from which mercury is obtained. Minute samples have been identified on Euboea, Naxos, Chios, and Samos.[10] It was obtained in larger quantities during the Classical period from Iasos on the coast of Turkey, where Early Cycladic objects have been excavated from burial contexts.[11] The ore can be crushed and ground to form a rich red pigment.[12] Moreover, grinding cinnabar finely in the presence of copper can yield droplets of mercury,[13] suggesting a fascinating paired use of cinnabar and azurite, although there is no evidence that the Early Cycladic islanders used mercury for its traditional purpose of pulling flecks of gold out of a sandy deposit.[14] Another magical, mysterious substance, this time red!

As noted above, recent discoveries have revealed evidence of metalworking on the island of Keros, where a large number of deliberately broken marble figures were deposited in antiquity.[15] Perhaps there was a resonance between the mysterious transformations of colors (ores) into metals and the transformation of those colors into features on the Early Cycladic marble figures.[16] Perhaps another sort of transformation, of meaning, was accomplished by the act of smashing the figures.[17]

What of the painted motifs themselves? The depiction of eyes, usually in their expected location on the face but occasionally in non-anatomical places on the face or body, is the most common motif. Hair is frequently depicted as well, often squared off at the back of the head, sometimes with curls or shorter straight pigtails or with straight or curled sidelocks. A clean, solid area visible across the crown of many figures may represent the beginning of the hair mass, or it may be all that remains of a headdress. On a few occasions, I have noticed discrete lines of a dot pattern beginning at the bottom edge of the headdress and continuing down the forehead. In rare instances where a mouth is depicted, it is usually almond-shaped and placed at an angle on the face, sometimes encompassing the bottom of the nose. These are not depictions of silent, closed lips. Several figures display facial markings that may mimic patterns painted or tattooed on women’s faces in the Early Cyclades. Rows of dots or vertical stripes on the cheeks appear on a number of Early Cycladic marble figures, such as the head described below. Another common motif is the application of red paint in lines and grooves that define the upper and lower neck, and red between fingers or toes. The pronounced asymmetry in painted anatomical features is an intriguing contrast to the general symmetry of the overall form of the figures. Four examples in the Stern collection serve as an introduction to the painted details on Cycladic figures.

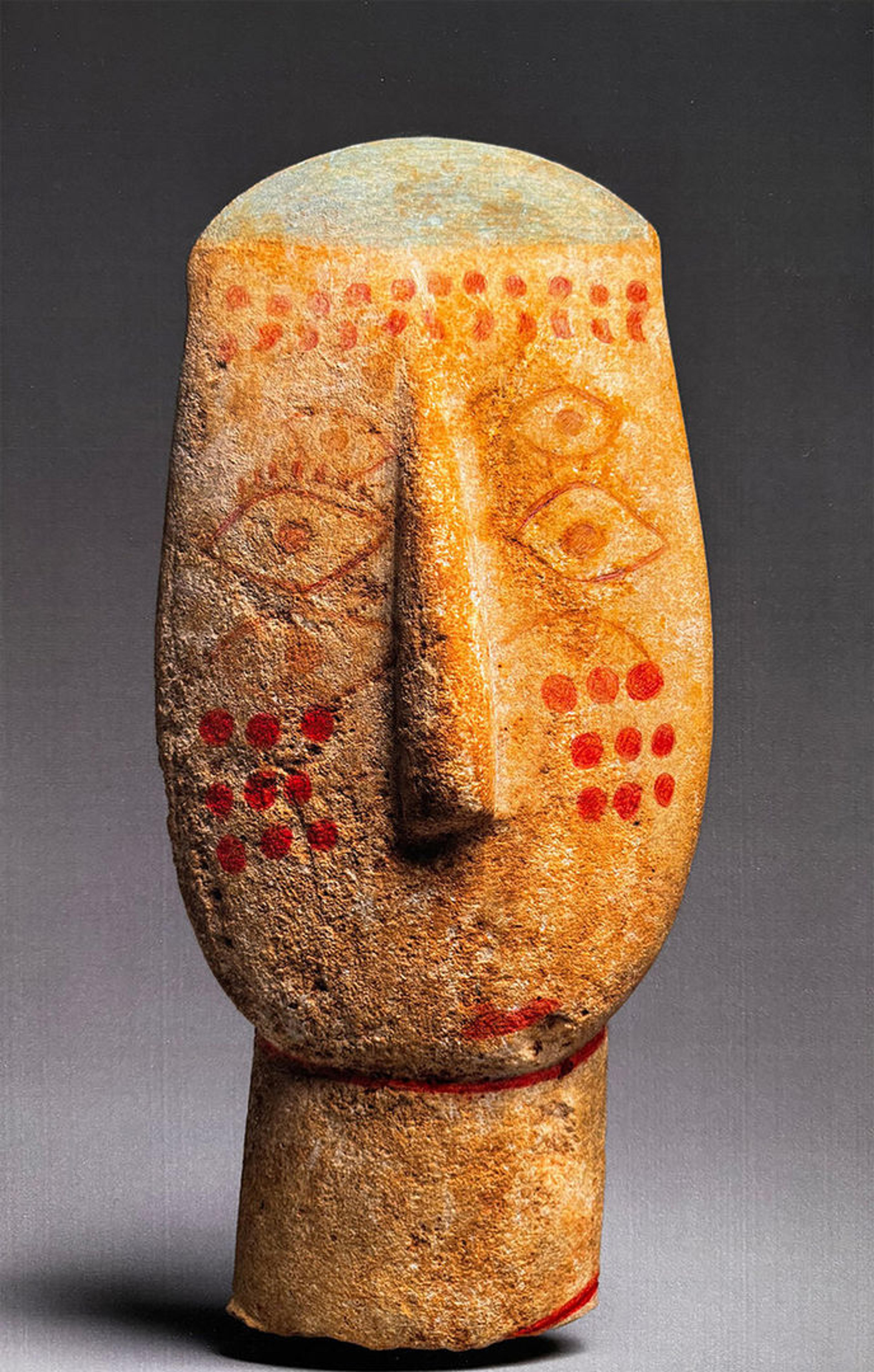

Marble female figure, ca. 2500–2400/2300 BCE. Early Cycladic II. Marble, 6 5/16 in. (16 cm). Leonard N. Stern Collection, Loan from the Hellenic Republic, Ministry of Culture (L.2022.38.44) . Color reconstructions by Elizabeth Hendrix

Astonishingly well-preserved remains of paint can be seen on a head fragment that is stylistically consistent with figures of the Spedos type. Despite some significant damage to the surface of the stone, an impressive amount of red pigment remains on the face, which has been identified as cinnabar.[18] Interestingly, the eyes are not preserved as raised “ghosts,” but as darker areas on the stone. Fine particles of brownish-red pigment can be seen at the edges of the pitted pattern that indicates the shape of the eyes and what appear to be eyelashes and pupils. Red coloring survives to depict a line of wavy fringe or dot pattern below the smooth paint ghost across the top of the crown. A carefully painted pattern of three rows of three red dots on the left cheek was probably also painted on the right cheek, where traces of red remain in vestiges of a similar pattern. Despite the remarkable preservation of the painted facial features, no painted mouth could be discerned on this figure, although there is a streak of red at the bottom of the chin. Red pigment was used to accentuate the incisions below the chin and at the base of the neck. Fainter traces of a double set of eyes appear above the anatomical eyes, and there may be two more eyes depicted below the anatomical eyes.[19] On the back of the head, the hair was painted with a medium that protected the stone from weathering; by contrast, the marble to the right of the hair mass is distinctively eroded outside the boundary of the painted hair. Strands of curling hair are painted down the back of the neck. They are visible as slightly darker areas on the stone.

Ethnographic parallels for face painting are relatively common worldwide and are usually applied to commemorate a specific event for a limited time.[20] Tattoos, though permanent, can mark an occasion, a rite of passage, or signify the status of an individual. The rows of painted red dots on the cheeks that I have observed on at least fourteen Early Cycladic figures, including this head fragment, may have marked an occasion in the life of the individual depicted. Perhaps less well-preserved motifs, such as the multiple eyes, were applied as part of a performance featuring the marble figure. Once the event was over, those motifs might have been cleaned off or allowed to fade and therefore were less likely to survive its long deposition.

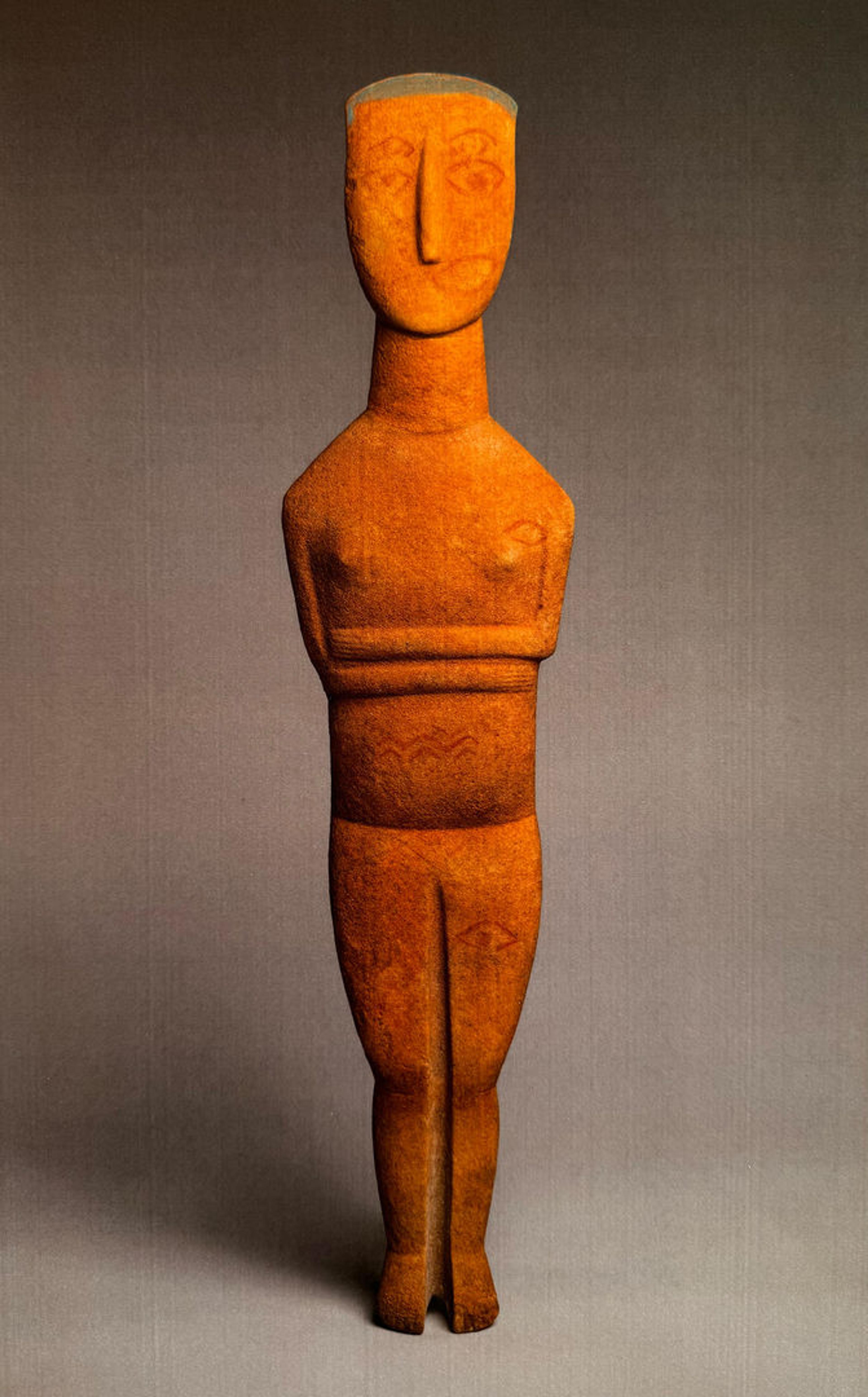

Marble female figure, ca. 2700–2400/2300 BCE. Early Cycladic II. Marble, 8 1/2 × 34 in. (21.6 × 86.3 cm). Leonard N. Stern Collection, Loan from the Hellenic Republic, Ministry of Culture (L.2022.38.22). Color reconstructions by Elizabeth Hendrix

The very large, well-preserved Spedos figure that is featured in the augmented reality reconstruction has perhaps the most striking eye and hair paint ghosts in the Stern Collection. Two eyes with pupils immediately confront us with eyebrows that create a gaze that can only be described as intent. The smooth area across the crown indicates the presence of a headdress or hair. A small area of red pigment at the bottom of this area has been identified as a modern pigment. This can be ignored except for its function as a reminder that the figures have been affected by the accidental marks of modern humans. Two straight sidelocks were painted in front of the carved ears. The hair was squared off at the back of the head, with two short pigtails, a specific hairstyle that I have documented on at least six other figures.[21]

Unfortunately, the highly deteriorated surface of the marble obscures evidence for other painted designs or features, except for perhaps one extra eye shape centered between the eyebrows and crossing over the top of the nose. The pubic triangle is also preserved as a paint ghost, and there are extant particles of red pigment between the toes and in the groove that separates the head from the neck. To survive in such a pronounced way, the paint ghosts must have been painted with thick water-repellant paint just before the figure was buried intentionally or otherwise. Here, too, the subtle asymmetries of the eyes and pigtails conspire with the differently placed ears to remind us that symmetry was not imperative; rather, the asymmetry may serve to animate these enigmatic figures.

Marble female figure, ca. 2500–2400/2300 BCE. Early Cycladic II. Marble, 24 7/16 in. (62.2 cm). Leonard N. Stern Collection, Loan from the Hellenic Republic, Ministry of Culture (L.2022.38.58). Color reconstructions by Elizabeth Hendrix

A large Spedos-style figure in the Stern collection looks remarkably similar to a figure in the Naxos Archaeological Museum, both in sculptural form as well as in some of the painted motifs.[22] The latter figure has a clear set of eyes and more eyes on the cheeks, across the throat (with green pigment preserved on the lower arc), and on the belly. In addition, a zig-zag was painted across the chest, parts of faded vertical zigzags are discernable on the legs, a band across the top of the crown can be seen as a paint ghost, and an open almond shape was placed in the mouth area. The paint ghost hair at the back of the head ended in two points, with possible curls on the back of the neck.

The figure in the Stern collection has a similar crown band, mouth lozenge, multiple eyes with pupils, as well as a zig-zag across the belly.[23] Darker lines on the figure’s left thigh and at the top of the incision delineating her left upper arm may be vestiges of zig-zags or almond shapes—although I am less confident in these patterns. In addition to sidelocks, paint ghosts at the back of the head show a hair mass with multiple curls extending down the back of the neck. Both figures were broken across the neck and the knees. These figures exhibit some of the painted motifs that are most difficult to understand and perhaps because of that, the most difficult to see. Their similarity also invites us to consider a commonality of symbols as well as form, setting up an ongoing dialogue among the people and events surrounding each figure.

Marble female figure, ca. 2500–2400/2300 BCE. Early Cycladic II. Marble, 5 13/16 × 15 13/16 in. (14.7 × 40.2 cm). Leonard N. Stern Collection, Loan from the Hellenic Republic, Ministry of Culture (L.2022.38.10). Color reconstructions by Elizabeth Hendrix

An elegant Dokathismata-style figure has prominent paint ghosts describing eyes and eyebrows (or perhaps part of a double set of eyes on the left side of the face). The depiction of hair is also preserved as a paint ghost, best observed as a sidelock on the left side of the face, arcing slightly toward the back of the head. I was not able to determine how the rest of the hair was depicted. There are particles of red pigment in the leg incision on the front of the figure. I have not seen ancient pigments in the leg incision, although I have seen modern colors rubbed off in this location from mount elements. Analysis of this red could suggest an ancient or modern origin for this pigment.

The breaks on this figure occurred across the neck beneath the chin, across the torso at breast height, across the belly just below the folded arms, and of course, across the shins, as evidenced by the missing feet. These breakages are typical on numerous figures and may be seen as perhaps the final activity in their use-life. The marble figures are not easy to break, and the consistent placement of these breaks signals a direct intention. The act of breaking the figures in a very specific way heightens the significance of the figure’s role in ritual. (I use the term ritual advisedly: the fact that this broken pattern happened so often implies, to my mind, that it happened according to cultural prescription).[24] The pattern of breakages was similar across a long period of figure production, as the examples noted above attest; this part of the ritual, at least, along with the painted eyes, endured over many generations.

While specific interpretations remain speculative, it is no stretch to acknowledge that the figures held special significance to their makers and audience beyond beauty and artisanship. Despite centuries that likely separate these figures, the painted motifs, particularly the eyes, were applied with notably similar effects. Though the body’s contours shifted over time, these marble figures were still recognizable as appropriately abstracted female forms, with consistent attention paid to the head, as the addition of painted eyes on the face attests.[25] Fertility is not the focus of these figures—they rarely depict pregnant bellies, and they have very small breasts and narrow hips. Rather, the common application of painted eyes on the prominent head demands that we pay attention to the spirit behind those eyes. She had much to convey. The rare, open mouth seems to suggest that when it was depicted, she and her human counterpart(s) would partner together to tell the stories of what it meant to live in their world. When no mouth was depicted, she assisted her human partner by embodying the stories in other ways. While some of the painted designs were likely permanent—the anatomical eyes and hairstyles—other designs may well have been applied to tell a specific story or provide a specific power—like ensuring a successful outcome for household and community members making a dangerous sea voyage—all the while confirming for makers and viewers alike membership in their current version of an Early Cycladic society.

Notes

[1] Hendrix 2003a, p.427, fig.13, showing a textile pseudomorph on the arms and belly of a large marble figure.

[2] see Hendrix 2000, Appendix II, Catalog of Excavated Finds of the EC Cultures, pp. 195, 211, 217, 221, 227, 229, 230, 231, 232, 233, 235.

[3] Wolters 1891 illustrates face stripes on a figure from Amorgos.

[4] For an illustration of the relative size differences of these two pigments, as prepared by the EC islanders, see Hendrix 2003b, pl. XXIX a and b.

[5] Getz-Gentle 1996, p. 260., comment with D19, suggesting the “jade-like stone handle” for an awl found in a marble bowl that contained red pigment might have been a “paint applicator”, given its context in the bowl.

[6] Broodbank 2000, pp.79–80, and fig.19. See also Nakou 1995 fig.6, and Hadjianastasiou and MacGillivray 1988 for copper sources on Kythnos.

[7] Broodbank 2000, p. 266, fig 87.

[8] Coleman 1977, pp. 3–4, 157–158.

[9] Georgakopoulou 2018, p. 532.

[10] Carter 2008 with references.

[11] Broodbank 2000, p. 301.

[12] Gettens and Stout, pp. 170–173.

[13] Marchini et al. 2022.

[14] The informative medieval treatise On Divers Arts by Theophilus describes in Chapter 49 the process of rubbing mercury into sand flecked with tiny particles of gold until the gold is fully alloyed with the mercury.

[15] Broodbank, 2000, pp. 230–231; Renfrew 2007; Georgakopoulou 2018.

[16] see Marchini et al, p. 7 for the cultural implications of some ancient alchemical choices.

[17] For a robust discussion of this topic see Renfrew 2007, esp. pp. 435 - 441.

[18] XRF analysis performed in the Department of Scientific Research at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

[19] See also Fig. 3, plus another figure in the Stern Collection, L.2022.38.154, for possible double sets of eyes.

[20] see Talaylay 1993 and Hoffman 2002 for reviews of the relevant literature.

[21] Hendrix 2000, p.98.

[22] Hendrix 2003a, p.422, fig.8., Zapheiropoulou 1980, “Idol” no. 4675. Getz-Preziosi 1987 p.159 (No. 10).

[23] Getz-Gentle 1996, pp. 180-182 notes that terracotta “frying pans,” some with incised or stamped decorations of sea waves, longboats displaying zig-zags, and vulvas that also appear, and in the same way, on the majority of marble figures, were on occasion found with pigment paraphernalia.

[24] See Renfrew 2007 for a discussion of the deliberate breaking of marble figures at Dhaskalio Kavos on Keros.

[25] Doumas 1977, pp.55–58 notes that in multiple burials the skeletons of previous individuals might be removed, but the skulls were saved and the new skeletons placed with them, evidence of the special significance accorded heads.