Drawing inks are water-based media made from various plant and mineral colorants. Any given ink may vary in tone due to the purity and concentration of its ingredients and its degree of dilution. Historic drawing inks are commonly hues of brown, reddish brown, gray, and black. Beginning in the late nineteenth century, synthetic, chemically-processed colorants dramatically increased the range of hues available to artists.

Clockwise from lower left: quill pens, different types and colors of ink, modern felt- tip pens, brushes, steel nibs and steel-nibbed pens, reed pens

Traditional inks share certain properties with watercolors and can be made with comparable materials; however, watercolors always contain solid pigment particles. Inks, by contrast, can be composed of dyes and are of low viscosity, allowing them to flow smoothly from a pen. Before the invention of steel nib, fountain, and felt tip pens in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, artists used broad and narrow quill and reed pens.

Ink may be applied with a pen or a brush to achieve either linear or tonal effects.

Inks may be diluted to produce lighter washes. Brighter areas and highlights may also be achieved by scraping ink from the paper.

Four types of ink derived from natural substances traditionally have been used for drawing: carbon-based or lamp black, iron gall, bistre, and logwood.

From left: 1: carbon black ink/candle and soot; 2: oak gall ink/oak gall nuts, iron compound, gum arabic; 3: bistre/chimney soot; 4: logwood ink/wood splinters

Lamp black ink has been used since antiquity. This stable carbon, soot-based ink is made by burning oils or pine resins. It produces strong linear marks and can be diluted to create transparent gray washes. It was popular in Northern and Central Europe in the sixteenth century and experienced a revival in the nineteenth century.

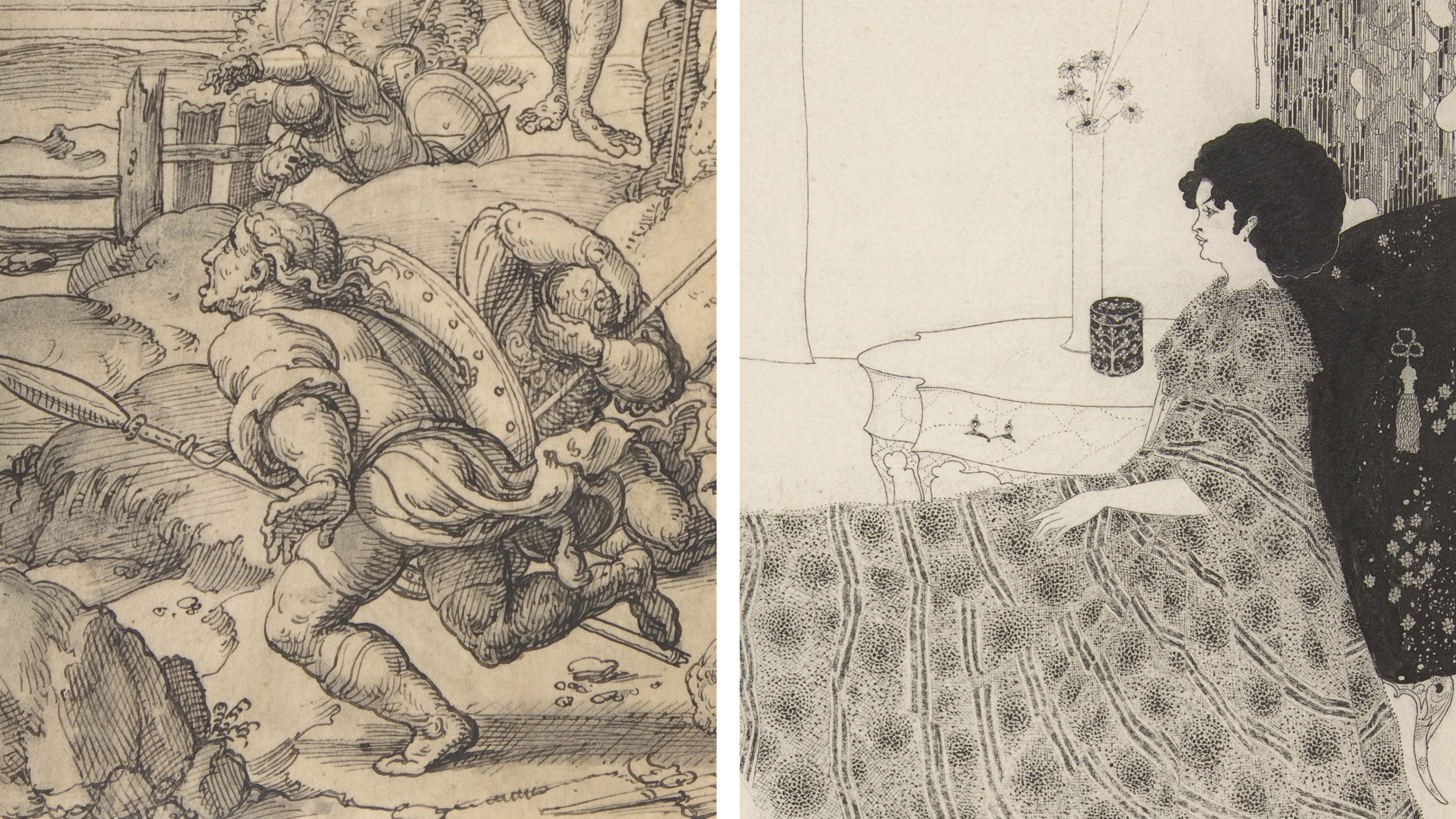

Left: Bernard van Orley (Netherlandish, ca. 1492–1541/42). The Resurrection (detail), early 16th century. Pen and black ink, grey wash, 9 1/2 x 7 3/4 (24 x 19.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Guy Wildenstein Gift, 2008 (2008.45). Right: Aubrey Vincent Beardsley (British, 1872–1898). Madame Réjane (detail), 1894. Pen and carbon black ink, and brush and wash, 14 x 9 1/8 in. (35.6 x 23 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1952 (52.64)

Iron gall ink, the most widely used ink from the twelfth to the mid-nineteenth centuries, is a combination of metal salts, tannates derived from plants, and a binder, such as gum arabic. The most common ingredients were gall nuts (growths on oak trees) and ferrous sulfate or metal filings. This ink is colorless when initially prepared, then oxidizes to a rich black. Upon aging, it often becomes brown or a rusty orange, changes that result from its particular components, recipe, and prolonged exposure to light. When prepared well, it is stable and combines with the fibers of paper preventing its erasure. When highly acidic, however, it may strike through to the underside of the paper and cause the ink to fracture.

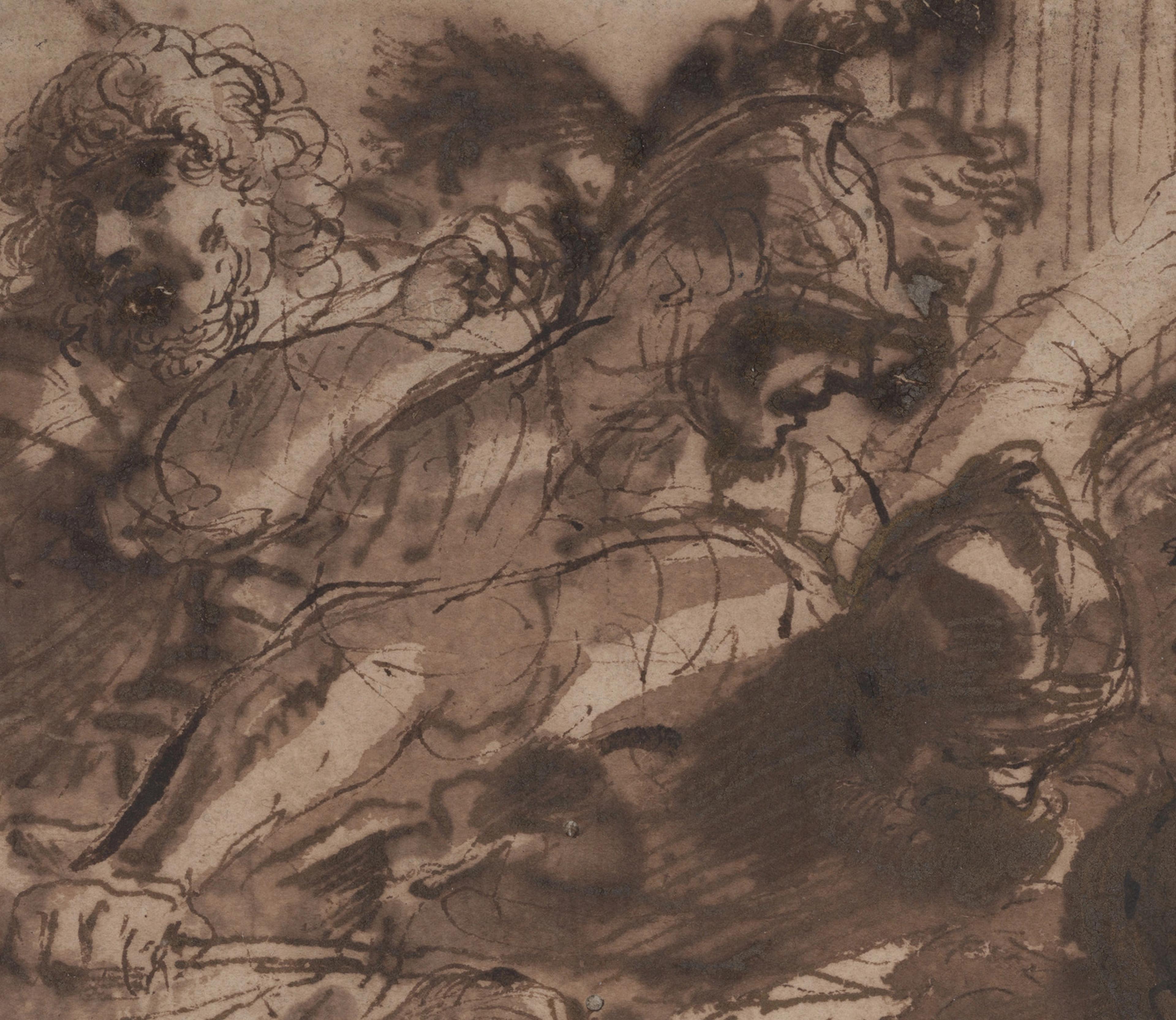

Guercino (Giovanni Francesco Barbieri) (Italian, 1591–1666). Samson Captured by the Philistines (detail), 1619. Pen and dark brown (iron gall) ink with brush and two hues of brown wash, 9 5/8 x 11 in. (24.3 x 28 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Leon D. and Debra R. Black, Mr. and Mrs. Mark Fisch, Charles and Jessie Price, and Mr. and Mrs. David M. Tobey Gifts, in honor of Mrs. Charles Wrightsman, 2018 (2018.196)

Bistre is made with wood soot collected from chimneys. Its color ranges from shades of reddish brown to grayish brown. It is used as a watercolor pigment and an ink. Its consistency is generally uniform, but will appear grainy if not well-filtered. Bistre was used relatively infrequently as an ink, but the term became a common descriptor of color for both ink drawings and watercolors. It is hard to identify bistre in a drawing without chemical analysis. The ink in the Fragonard drawing below is believed to be bistre.

Jean Honoré Fragonard (French, 1732-1806). The Sultan (detail), 1774. Brush and brown wash (possibly bistre) over black chalk underdrawing, 14 1/4 x 11 1/4 in. (36.2 x 28.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Catherine G. Curran, 2008 (2008.437)

True sepia is a substance derived from the ink sack of a cuttlefish. Difficult to make, it is rarely found in drawings, and is not shown in the image of ink types above. Like bistre, the term sepia has more often been used to describe color than to identify the actual substance. When applied with a pen it is usually called sepia ink, and with a brush, sepia watercolor or wash. Drawings said to be "sepia" most often contain a mixture of pigments that approximate the reddish to gray brown hues of the true ink. An example of sepia-colored wash, its constituents unidentified, appears in the Frederick Catherwood detail below, applied with pen and brush.

Frederick Catherwood (British, 1799-1854). Stela at Copán (detail), 1843. Sepia wash over graphite, 23 x 16 1/6 in. (57.1 x 40.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1953 (53.82)

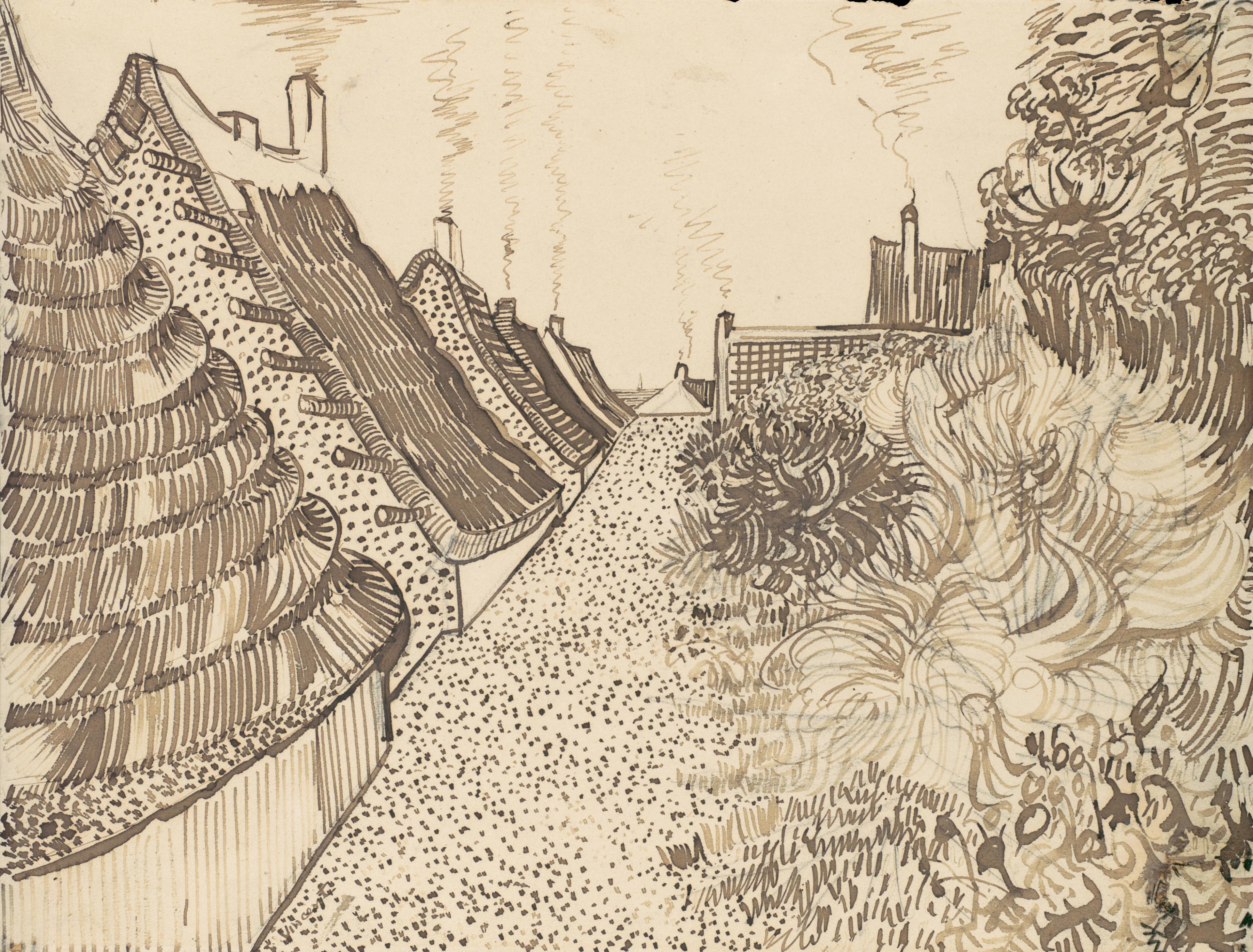

In the nineteenth century, logwoods and synthetic inks, such as anilines, gradually replaced iron gall, or ferro-tannate, inks. Not only were they cheaper, but they also did not degrade the newly-introduced steel nib pens. Vincent van Gogh notably used logwood inks, favoring their rich black color and the expressive quality of a reed pen to apply them. Inevitably, these drawings faded to brown and orangey hues, as seen below.

Vincent van Gogh (Dutch, 1853–1890). Street in Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, 1888. Reed pen, quill, and ink over chalk on wove paper (backed with wove paper), 9 5/8 x 12 1/2 in. (24.3 x 31.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, 1948 (48.190.1)

See a selection of ink drawings from The Met collection.