Recent Acquisitions

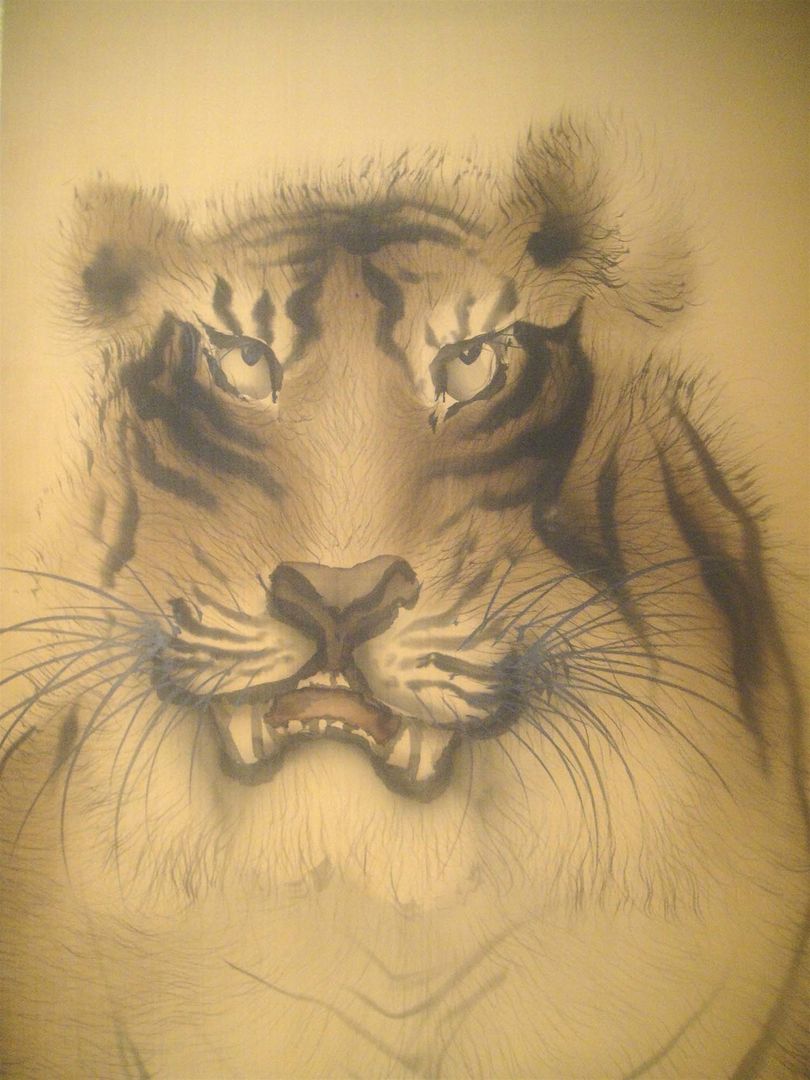

Tiger, Tigress, and Cub

John Carpenter, Mary Griggs Burke Curator of Japanese Art

A regal reclining tigress nurses her cub while her snarling mate stands poised to drink at a mountain stream. The landscape is rendered simply in ink monochrome, but the thick fur and sinuous muscularity of the tigers are painted in detail, with the color wash on their coats creating the impression of sunlight. Chikudō, the fourth-generation head of the Kyoto-based Kishi school, advocated sketching from life. Together with several of his contemporaries, he established a style that blended traditional Japanese painting with elements of Western realism and perspective. Like the founder of the school, Ganku, Chikudo became famous for his meticulous tiger paintings, one of which was exhibited at the 1893 Chicago World's Fair. The noted Asianist Ernest Fenollosa commented on that piece:

Having painted for this exhibition four tigers which he successively destroyed as unsatisfactory, Chikudō at length produced this at the price, it is said, of temporary mental derangement—his prolonged absorption in his conception having induced the illusion that he was himself a tiger.

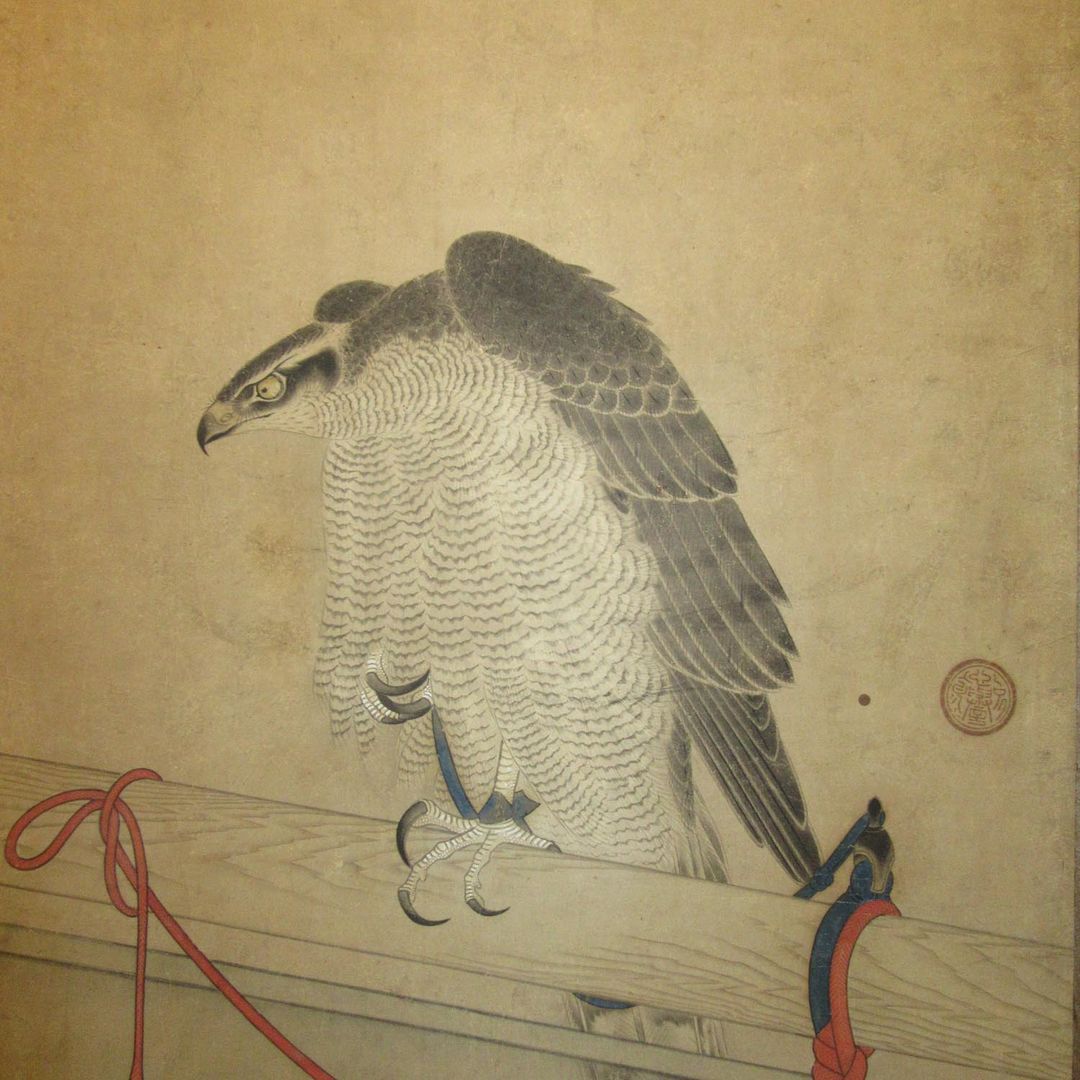

Tethered Hawks

John Carpenter, Mary Griggs Burke Curator of Japanese Art

Hawks tethered to their perches, awaiting their masters to release them for the sport of hawking, symbolize military preparedness and valor. Their fearsome beauty and predatory features—sharp beaks, keen eyes, long curving talons—made them metaphors of martial training and the warrior spirit. Falconry in Japan was first practiced at by members of the court aristocracy and later mainly by feudal chieftains (daimyo) and other elite samurai. Soga Chokuan was renowned for his hawk paintings and received many commissions from leading samurai. This set of paintings is inscribed by the prominent Zen monk Ittō Jōteki. Along with serving as the 152nd abbot of Daitokuji in Kyoto, Jōteki is famous for being the teacher of Monk Takuan, one of the most famous Zen monks of the Edo period. Monk Jōteki hosted Toyotomi Hideyoshi—regarded as "the Napoleon of Japan"—at a tea gathering at Daitokuji temple just a few months after the assassination of Oda Nobunaga in 1582—just the time Hideyoshi was consolidating power as the dominant warlord in Japan.

Narasimha Destroying the Demon King

John Guy, Florence and Herbert Irving Curator of the Arts of South and Southeast Asia

Narasimha, the man-lion avatar of Vishnu, in the climactic moment of the King Hiranyakashipu myth, disembowels the demon king with his claws. Vishnu descended in this ferocious form to slay the evil king for repeatedly trying to kill his own son Prahlada for his unwavering devotion to Vishnu. Prahlada and his wife stand in witness, their hands raised in veneration. The palace setting in which this miraculous event occurs is conceived as a Victorian courtyard, with highly ornate scroll work bracketing the scene. This is an impressive work of the Chitrashala Printing workshop, active in Pune in western India. The press employed lithographic printing technologies newly imported from Europe. Artists formerly employed in court painting were now recruited to reproduce chromolithographic prints for popular devotional use. This technology made images of the Hindu gods accessible for mass consumption in India for the first time. Even the humblest home could afford a colorful icon of their chosen god to display in the household shrine.

Censer

Pengliang Lu, Associate Curator

This censor exemplifies how late Ming craftsmen creatively revived archaic prototypes. Based on a Han dynasty bronze incense burner, the piece is not a slavish copy; rather, its playfully animated form and decor mark it as a brilliant antiquarian creation. In Ming times, this mythical creature was identified as a luduan, an auspicious unicorn that was able to master the language of every land it traveled through but would only appear when a virtuous ruler was on the throne. Porcelain sculptures of this scale are prone to distortion during the firing process, which explains their rarity. The powerful form and elegant underglaze blue painted décor of the present example distinguish it as arguably the finest early seventeenth-century porcelain sculpture of this type to survive.

Japanese Kimonos

Monika Bincsik, Diane and Arthur Abbey Assistant Curator for Japanese Decorative Arts

From left: Noh robe (Atsuita), 18th century. Edo period (1615–1868). Twill-weave silk. Purchase, Diane and Arthur Abbey Gift, 2018 (2017-8.642). Summer robe (katabira) with The Tale of Genji design, late 18th century. Edo period (1615–1868). Ramie with resist-dyeing, silk and gold thread embroidery. Purchase, Friends of Asian Art Gifts, 2018 (2018.638). Unlined summer robe with autumn flowers and insect cages, late 18th to early 19th century. Edo period (1615–1868). Ramie with resist-dyeing, silk and gold thread embroidery. Purchase, Friends of Asian Art Gifts, 2018 (2018.643)

In Japanese art and material culture, textiles and garments are one of the most expressive and significant art forms. Variations in cut, color, and design convey information about the owner's wealth, gender, age, place in the social hierarchy, and marital status. Clothing's capacity to convey meaning has long been acknowledged in literature and the excitement aroused by new styles and patterns is reflected in folding screen paintings, portraits of beauties, and ukiyo-e prints. During the Edo period (1615–1868), there was a great flowering of the textile arts as an increased market for kimono and Noh robes proved a catalyst for both technical developments and the emergence of a vibrant textile-design culture. Thanks to the support of a number of individuals and the Friends of Asian Art, The Met has been able to acquire sixteen garments lovingly assembled by a Japanese textile dealer over more than two decades. This group, dating mostly to the eighteenth century, greatly enhances the quality of our holdings.