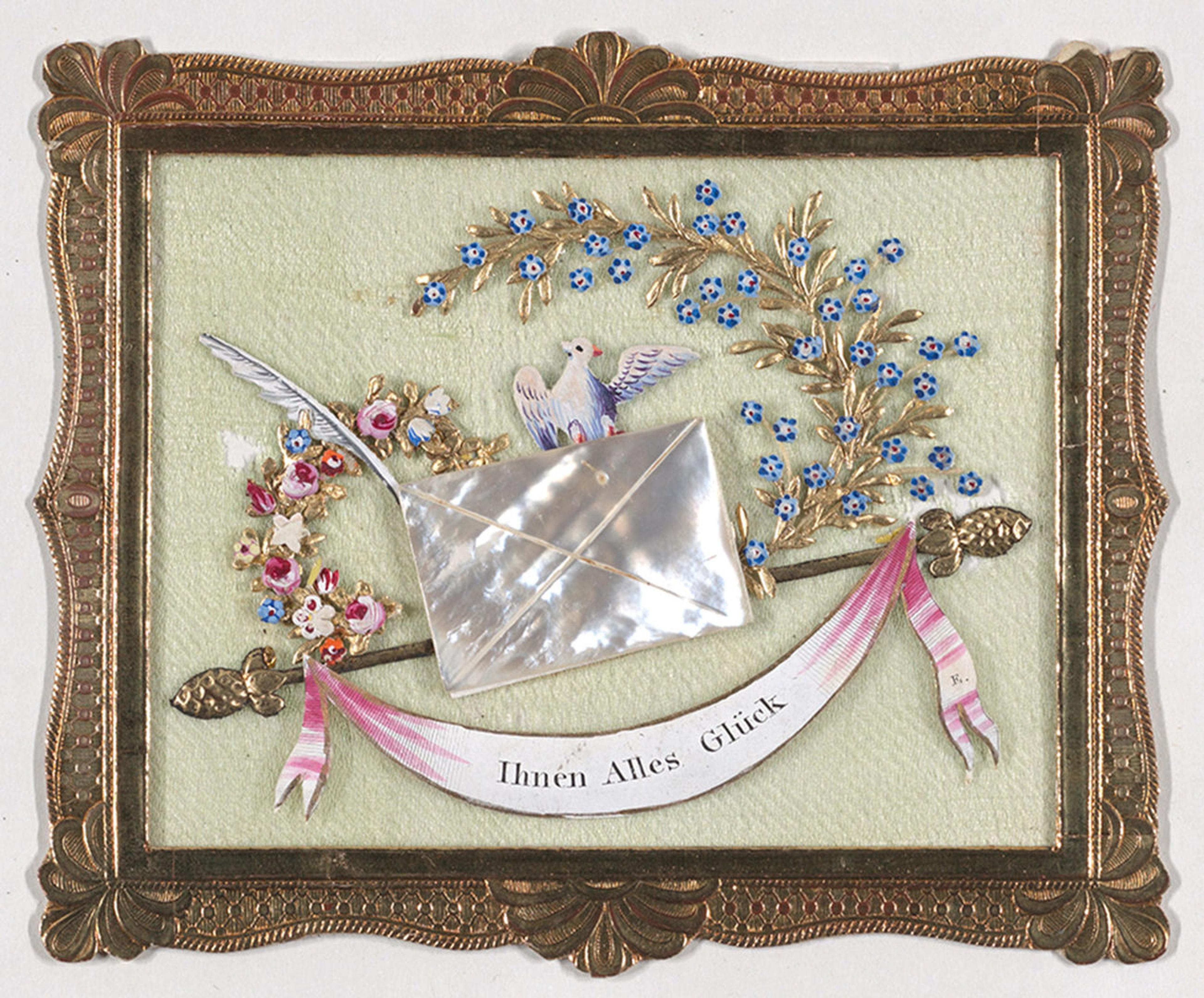

Johannes Endletzberger (Austrian, 1782–1850). Greeting Card, 1810. Gouache, metallic paint, metallic foil, embossed and punched paper, and carved and painted mother of pearl on silk, sheet: 3 1/4 × 3 7/8 in. (8.2 × 9.9 cm). Gift of Mrs. Richard Riddell, 1981 (1984.1164.1835)

The anniversary installation Collectors’ Collections, on view in the Robert Wood Johnson, Jr. Gallery in 2021, contained a group of Biedermeier-era greeting cards that were donated to the Museum by Mrs. Jean Riddell as part of a larger gift in 1981. The selection focused on the jewel-like cards produced in the workshop of Johannes Joseph Endletzberger (Austrian, 1782–1850), who was one of the best-known Viennese artisans who produced elaborate greeting cards that commemorated special holidays and served as expressions of friendship and love.

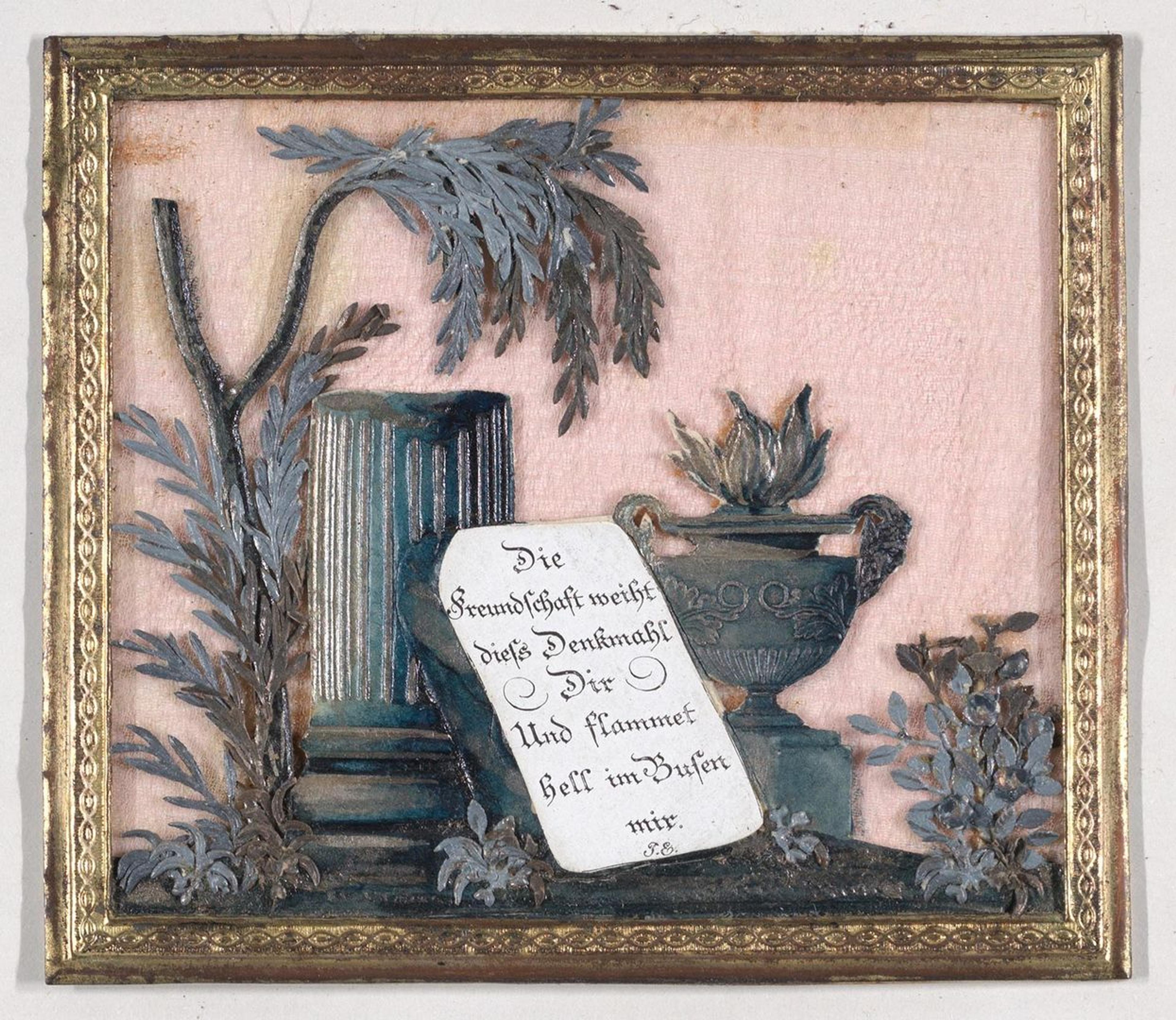

Johannes Endletzberger (Austrian, 1782–1850). Greeting Card, 1810. Gouache, metallic paint, metallic foil, embossed and punched paper, and carved and painted mother of pearl on silk, sheet: 3 1/4 × 2 11/16 in. (8.3 × 6.9 cm). Gift of Mrs. Richard Riddell, 1981 (1984.1164.1834)

From around 1750 to 1850, paper remembrances evolved from the simpler French cartes de visite (calling cards) to collaged tokens that incorporate romantic, floral, mythological, and everyday motifs, as well as poems and well-wishes that are often handwritten on the back. Originating in Vienna, the production of greeting cards eventually spread to Augsburg, Nuremberg, and Prague, where numerous craftsmen created richly embellished, jewel-like cards. Others resembled toys with movable pull-tabs and levers that yield surprising images, optical puzzles, and enclosed private messages.

The evolution of fine papermaking was a major catalyst for the boom in the greeting card industry. In its early stages, the greeting card had consisted of simple engraved images, but soon fine-quality paper products became the “canvas” for artistic creativity. The cards were made from pressed and cameo-embossed paper, and later intricate moveable mechanisms were also incorporated. The engineering involved in creating elaborate movable elements was meant to appeal to a sophisticated audience who also patronized the arts, including opera and ballet. For these audiences, fantasy greeting cards – especially ones with intriguing motion – were forms of entertainment that paralleled the performances and concerts they attended in their leisure time. As such, these cards embody the elegance and playful debauchery that defined the Homo Ludens (playing man) of the Biedermeier era.

Johannes Endletzberger (Austrian, 1782–1850). Greeting Card, ca. 1840. Gouache, metallic paint, metallic foil, and embossed and punched paper on silk, sheet: 3 1/16 × 3 1/2 in. (7.7 × 8.9 cm). Gift of Mrs. Richard Riddell, 1981 (1984.1164.1854)

The exchange of greeting cards between family members, friends, and business associates quickly became a status symbol for the increasingly more affluent middle classes in Eastern and Central Europe. The emergence of capitalism, and the fading influence of the church, prompted increasing emphasis on values such as happiness and healthy interpersonal relationships, which could be commemorated through sentimental images of clasped hands, wreaths, and iconic temples of friendship and marriage.

Johannes Joseph Endletzberger was born in 1782 in St. Polten (Austria) and began his career as an engraver of coins and banknotes in Vienna and Prague. Accustomed to working in a small format, he later translated those skills to the crafting of jewel-like compositions on cards. From about 1815 until 1840, he ran an atelier where he employed several artisans who created luxury greeting cards. Today, they are recognized for their exceptionally high quality in craftsmanship and the use of the finest materials available. Embellishments such as faux cabochons and pearls, reducing mirrors, mother-of-pearl, gold embossed paper, fabric flowers, mica, gold and silver threads, mirror shards, and even tiny handmade clay ornaments, all set upon transparent silk chiffon, reflect the magic that emanated from his studio. Small paper scrolls with delicately handwritten poems and well-wishes added sentiment.

Johannes Endletzberger (Austrian, 1782–1850). Greeting Card, 1821. Silver embossed paper frame, handwritten motto on white card stock, silk chiffon, silver Dresden” urn scrap, tiny floral embellishments made of a clay-like material, watercolor, and graphite, sheet: 2 5/8 × 3 5/8 in. (6.6 × 9.2 cm). Gift of Mrs. Richard Riddell, 1981 (1984.1164.1832)

Endletzberger cards set the standard for quality. The refined elegance of these rare adornments on silk have prompted some people to refer to him as “the Fabergé of Greeting Cards”. His gem-like cards were purposefully produced in limited quantities in order to maintain their status as luxury objects. But, as demand for fine greeting cards rose, so did his competition. There were many copyists of Endletzberger’s designs, which means that modern scholars and collectors have to contend with issues of attribution. The engraved initials “J. E.”, “I. E.”, or signatures “J. Endletzberger”, and “J. Endletsberger”, help to identify his sought-after creations.

Cards by Endletzberger and his followers are often colloquially called “Beidermeiers”— a reference to the style of the decorative arts popular in the German region during the first half of the nineteenth century. While the German name for the cards is Glückwunschkarten (“greeting cards”), they are also called billets, congratulatory or friendship tickets, and, oddly, train tickets. Depending upon the purpose, these cards could be used for romance, mourning, congratulation, New Year’s Day, Name Day, or Friendship. They are an essential link in the evolution of the valentine, from the earliest devotionals to the elaborate paper-lace Victorian confections.