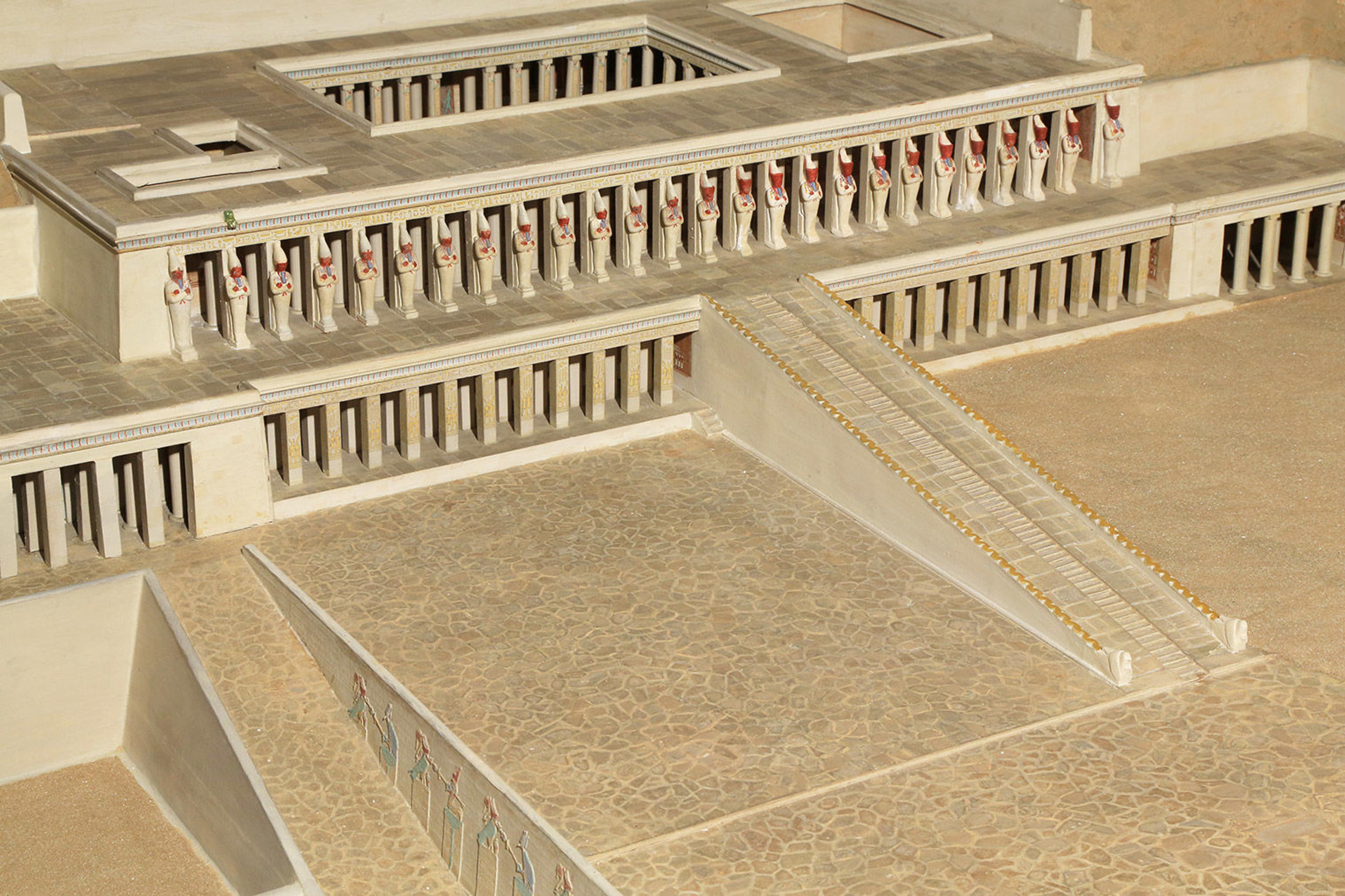

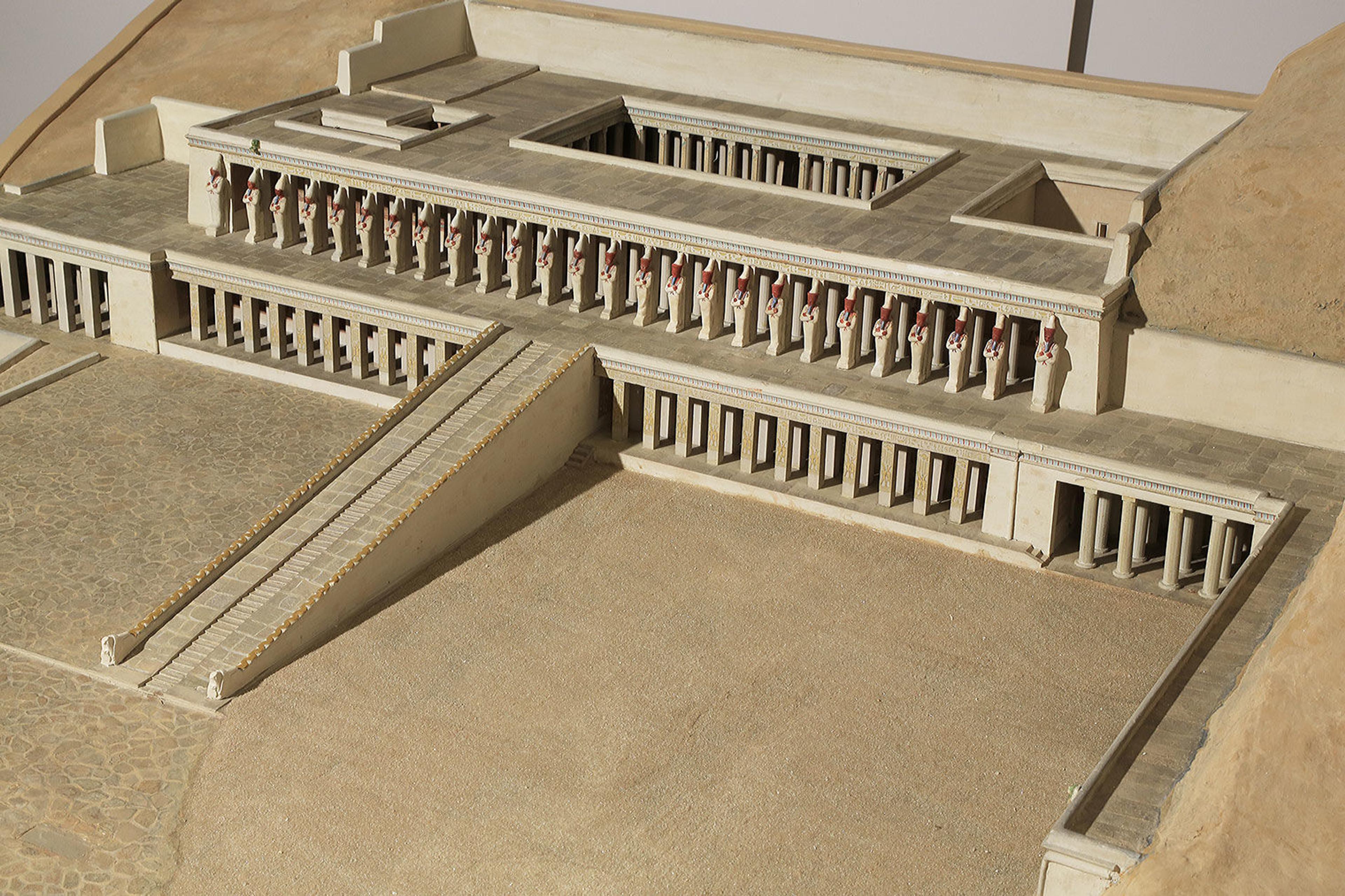

Fig. 1. The model of the temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahri with the triple tiered pillared halls and the connecting ramps. Original: Egypt; Thebes, Deir el-Bahri, Temple of Hatshepsut. Wood, plaster. L. 289.6 cm (114 in.); W. 124.8 cm (49 1/8 in.); H. 65.4 cm (25 3/4 in.). Funds from the Architects Relief Committee and the Work Relief Bureau, 1934. Photograph by the author. (2012.139)

The Model

Starting in 1911, the study of temples and tombs of the Middle Kingdom was the focus of the Museum’s work in western Thebes. From 1922 on, the work in the Asasif and Deir el-Bahri also incorporated the forecourt and lower and middle terraces of the temple of Hatshepsut but did not center on the architecture and decoration of the main part. Work was further encouraged in 1926 by the discovery of masses of broken Hatshepsut statuary at the Mentuhotep causeway and in the so-called Senenmut-quarry. The recovery of the sculptures of Hatshepsut resulted in a division of finds, which from 1929 on immensely enriched the New Kingdom galleries of the Museum. The new display of statues and statue fragments was enhanced by a full-size copy of the so-called Punt-wall of the temple (08.204.1–.6) and a plaster model of the temple of Hatshepsut. The model, produced 1934–35 in the Museum under project supervisor Howard I. Cornell, was based on a record of the architecture and decoration undertaken specifically for this purpose at the site. The naturalistic model was painted to include depictions of the wall decoration and was displayed surrounded by a depiction of the mountain cliffs behind the temple. However, the documentation of this display remained scarce and both the Punt-wall and the model were retired decades ago for a new arrangement of the galleries.

The longtime underground storage of the model caused some minor damage, which was fixed when, in 2013, the model was sent for an exhibition in Tokyo. The Museum’s conservator Ann Heywood revived the faded beauty of the model but did not replace the models of statues, as well as small figures of people that had been added for scale, all of which had disappeared. After that restoration, a new series of photos could be produced. However, the temple model was not brought back to be displayed in the Museum’s galleries, but is instead in long-term storage.

Architectural models of ancient buildings were highly appreciated in the past and once graced the galleries of The Metropolitan Museum of Art. The models of the pyramid complex of Sahure, the Hypostyle Hall at Karnak, the Parthenon, and the Pantheon were extraordinary examples of model building. In spite of the development of much more sophisticated modern 3D-models, “real” architectural models are still frequently used by architects and can still educate and fascinate visitors to museum exhibitions.

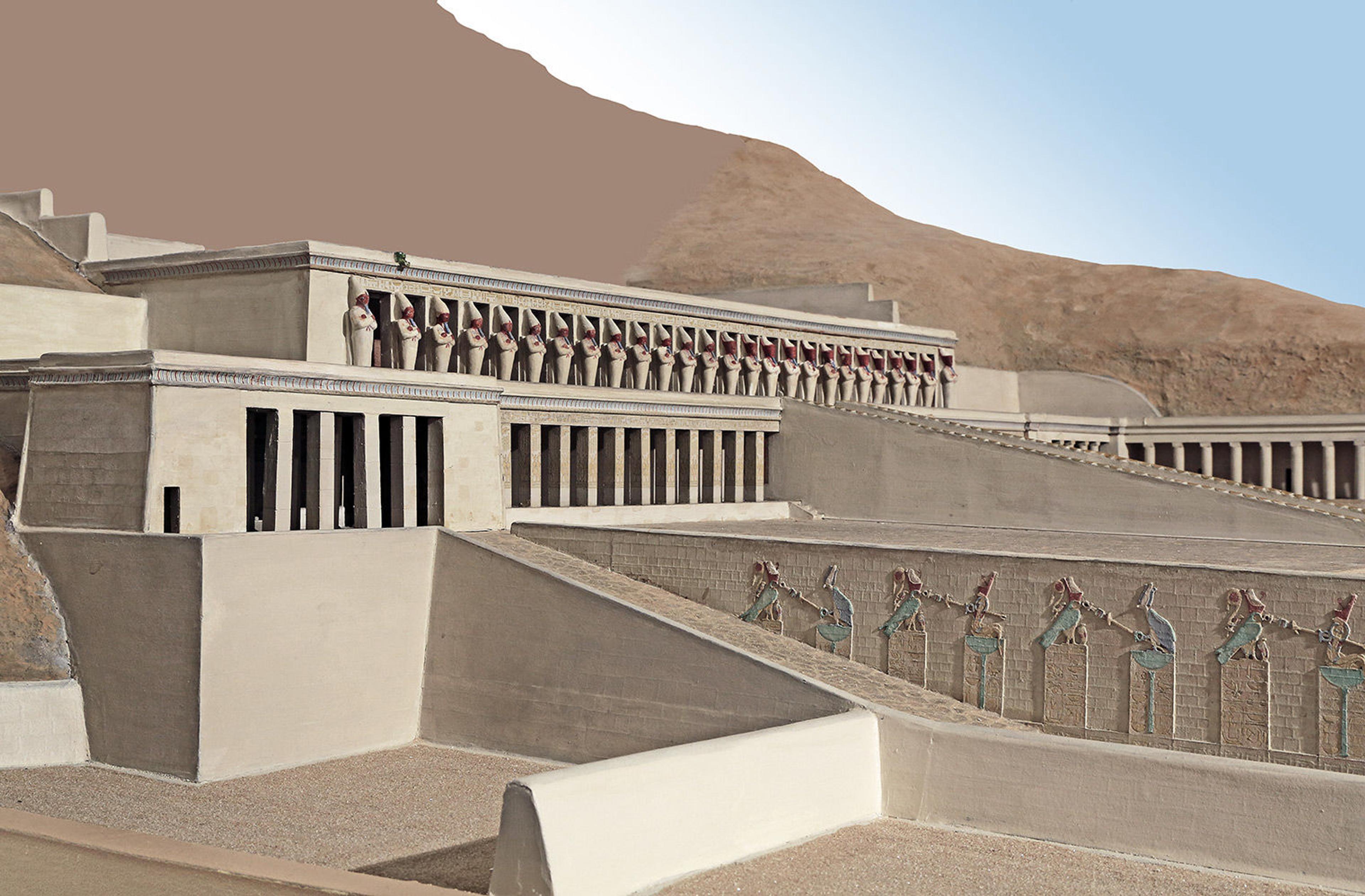

Fig. 2. Ramp leading to the Hathor shrine (lower left) and ramp leading from the middle to the upper terrace (center right). Photograph by the author

Fig. 3. Approach to the Hathor shrine (center left) covering the south side of lower terrace (lower right). Photograph by the author

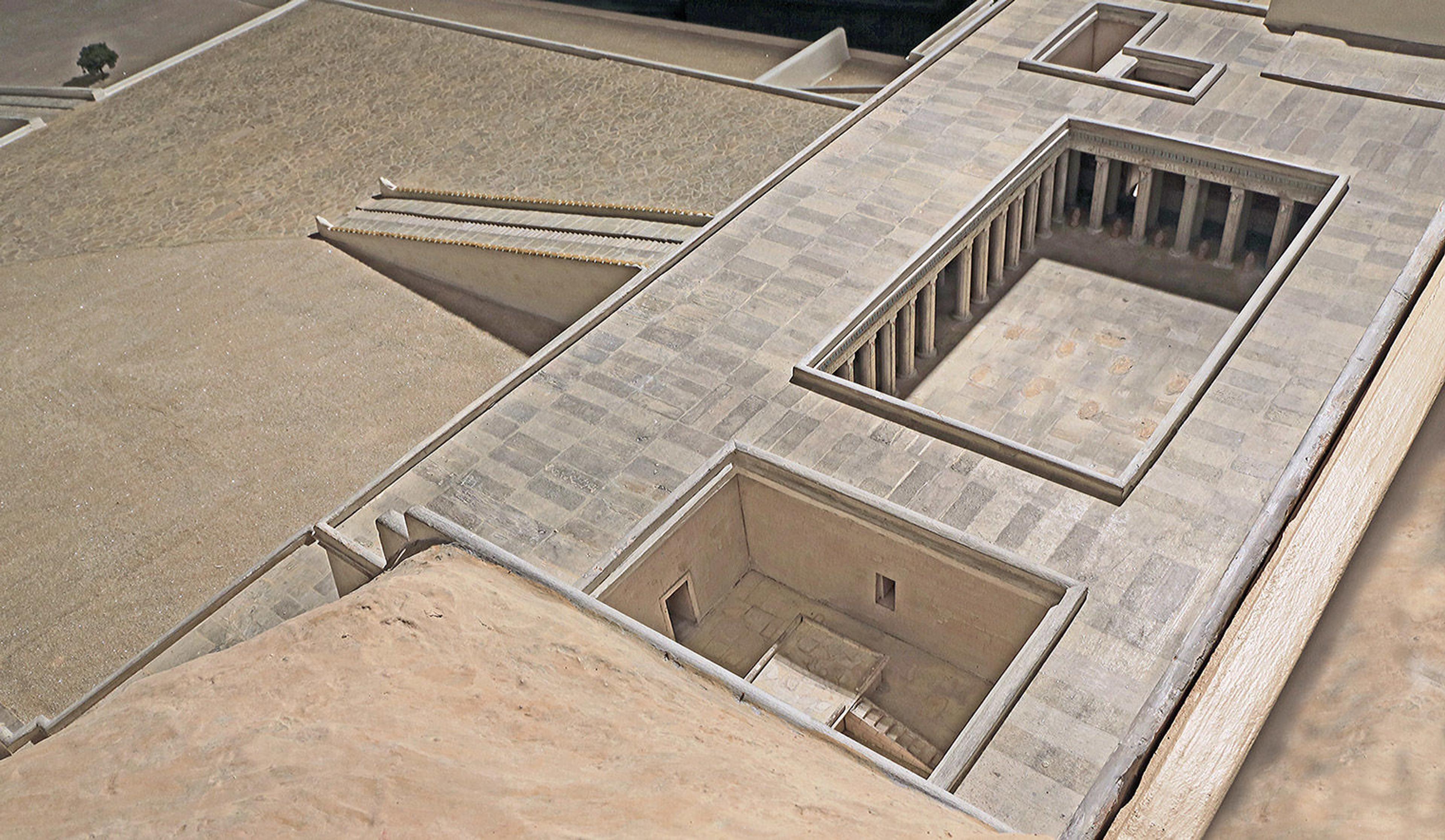

Fig. 4. The southern pillared hall on the lower terrace. Photograph by the author

The model omits the partially rock-cut rooms behind the splendid facade, which represented the actual religious focus of the building. However, even the real temple shows a proportional discrepancy between its modest interior rooms and the overwhelming exterior. In that respect, the model truly captures a major characteristic of a temple that was to some degree meant to be viewed from outside.

Fig. 5. Top view of the open-air sanctuary of Re and the inner court on the upper terrace. Photograph by the author

From the Eleventh Dynasty on, Upper Egyptian gods left their home temples to visit other sanctuaries in the area. The principal example was Amun-Re of Karnak, who regularly travelled to the Luxor Temple and the west bank of the Nile. The voyage required two related and structurally similar building forms, a smaller station or shelter en route (a way station) and a more substantial temple at the destination.

The earliest known example of a way station is the white chapel of Senwosret I at Karnak, a pillared baldachin elevated on a podium with ramps for the ascent and descent of the god’s barque.

Fig. 6. The kiosk of Senwosret I in the open-air museum at Karnak (chapelle blanche). Photograph by the author

The temple of the Eleventh Dynasty king Mentuhotep II Nebhepetre at Deir el-Bahri is the oldest known example of a temple that received such visits and is characterized by pillared halls elevated on a high platform ascended by a wide axial ramp.

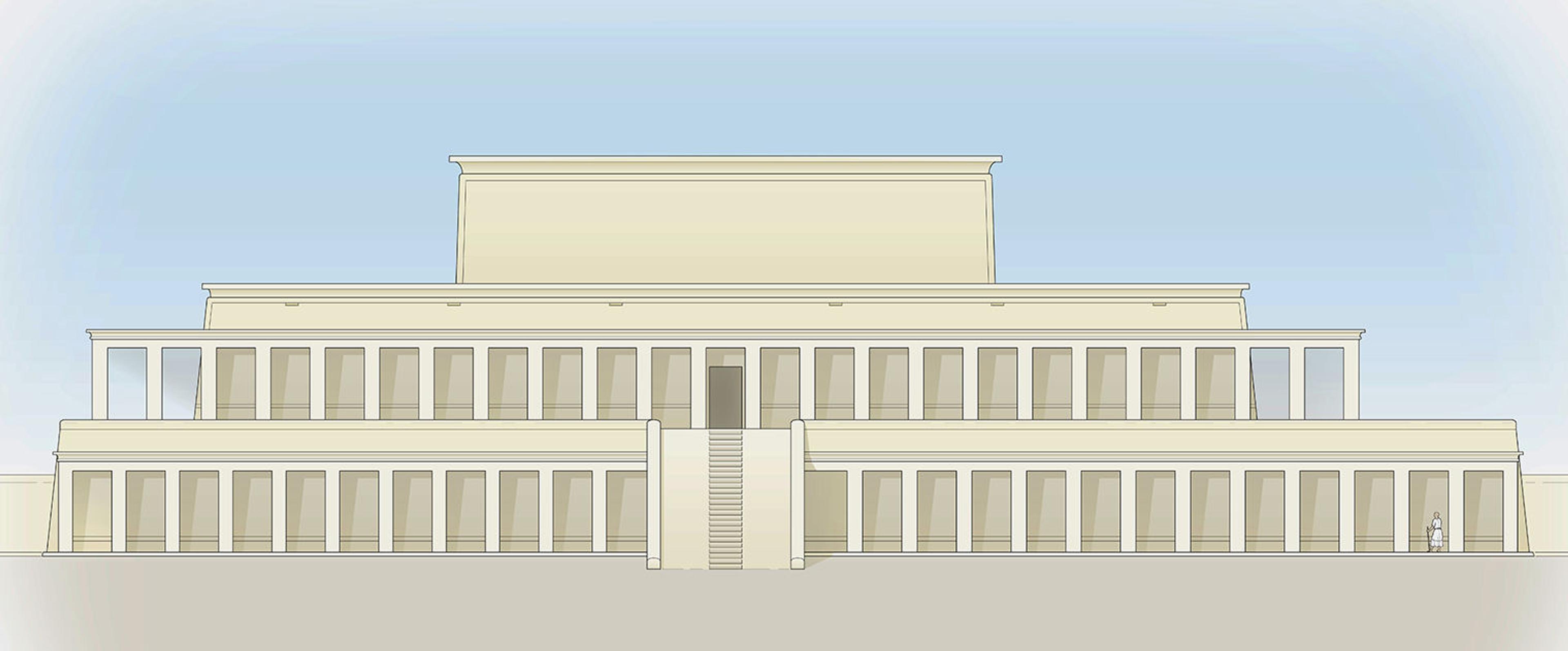

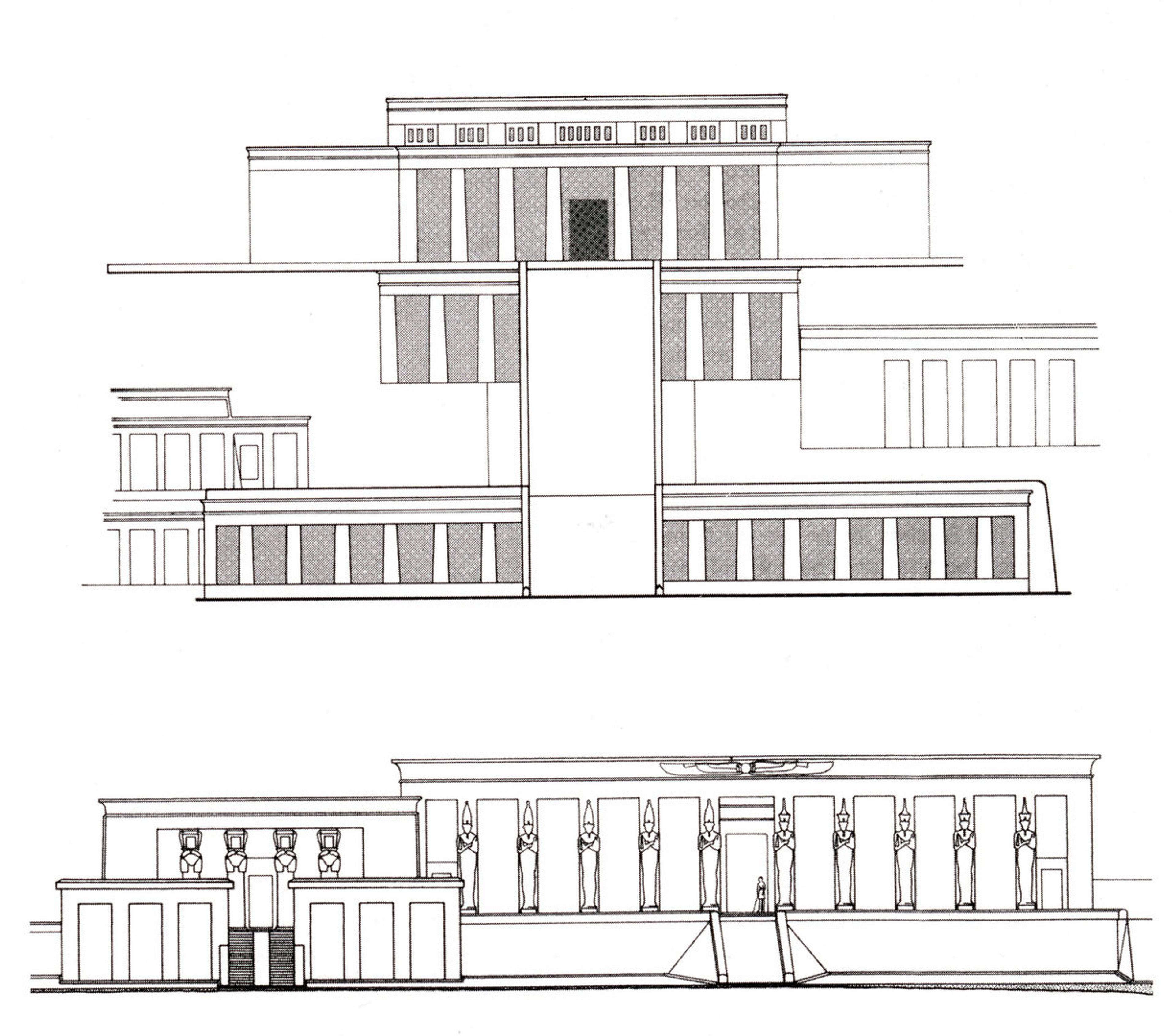

Fig. 7. Reconstruction of the front of the temple of Mentuhotep II Nebhepetre at Deir el-Bahri. Drawing by Sara Chen

Compared to the Mentuhotep temple, the Hatshepsut temple offers several innovations. Visually, the main alteration was the elimination of the central massif of Mentuhotep, leaving a wide, empty terrace. This opening enabled a direct axial approach for the bark of Amun-Re of Karnak, access that had been blocked in the Mentuhotep temple.

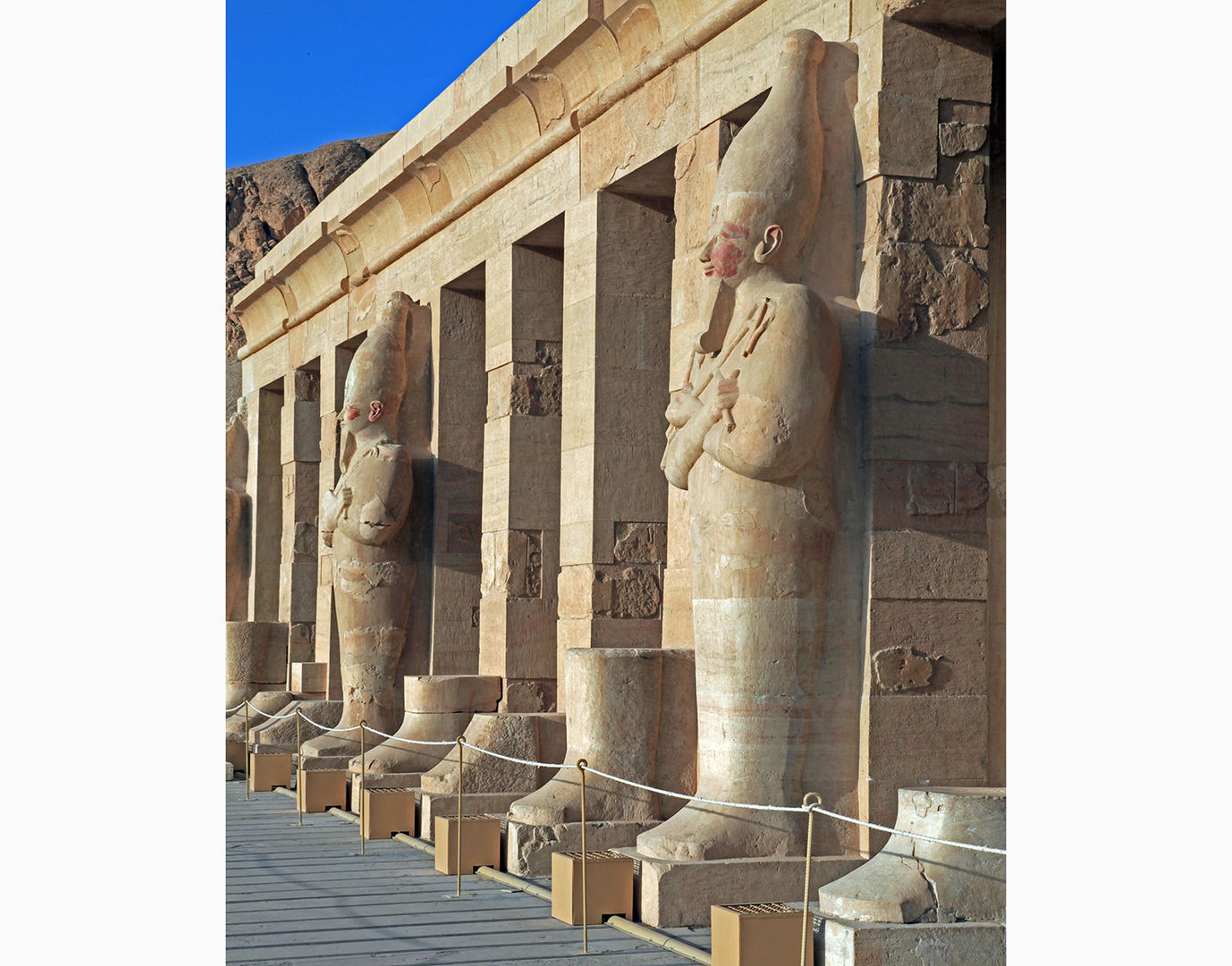

Another innovation that fundamentally changed the appearance of the temple was the overwhelming usage of over life-size “Osirides.” This element was not quite new. Royal statues in standing position existed already in the Mentuhotep temple and a row of twelve colossal royal “Osirides” formed the front of the Amun temple of Senwosret I at Karnak (Fig. 8).

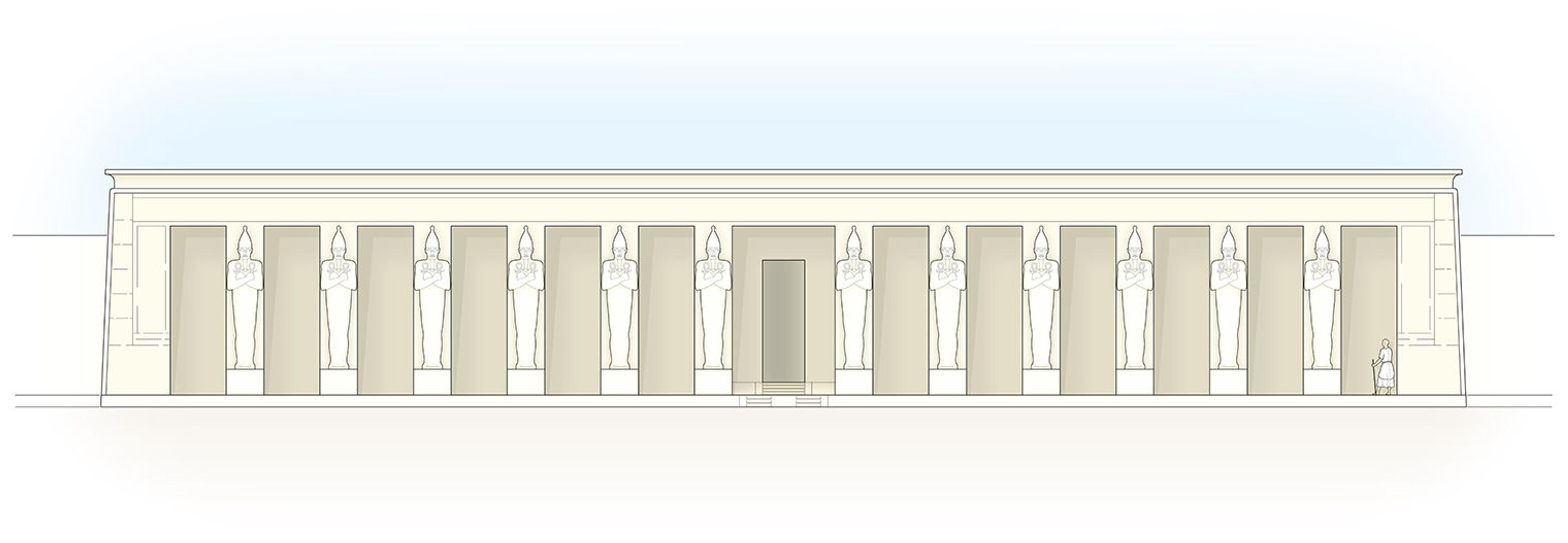

Fig. 8. Hypothetical reconstruction of the façade of the Amun temple of Senwosret I at Karnak. Drawing by Sara Chen

The exterior rows of Osirides of the Hatshepsut temple were part of an overwhelming, obviously unique statue program that included various statue types, different materials and locations in the temple area. The Met displays a broad selection of these restored statues in Gallery 115.

Fig. 9. The pillared hall on the lower terrace with the ramp leading up to the Osiride front of the upper terrace. Photograph by the author

In the pyramid temples of the Old Kingdom, the mortuary cult of the king was the dominant feature, culminating in the statue chamber and offering hall of the king. In the Hatshepsut temple, the central cult room belonged to Amun-Re of Karnak. The royal offering hall still existed, and in Hatshepsut’s temple additionally included an offering hall for her father, Thutmose I. However, Hatshepsut’s offering hall was, in spite of its splendid Memphite design, reduced to a minor side branch in the temple’s layout. There is no royal statue chamber any more for the personal cult of the king but instead, the royal element is exhibited outside in the form of twenty-six colossal statues along the temple front.

This accentuation of the exterior with the display of royal statuary suggests a change in the understanding of kingship. The rulers of the Old Kingdom were established without condition and their cult performed invisibly, hidden in the interior of the pyramid temples. The pharaohs of the New Kingdom, and especially Hatshepsut, may have tried to bolster their position by public demonstrations of their place in the line of ancestor kings.

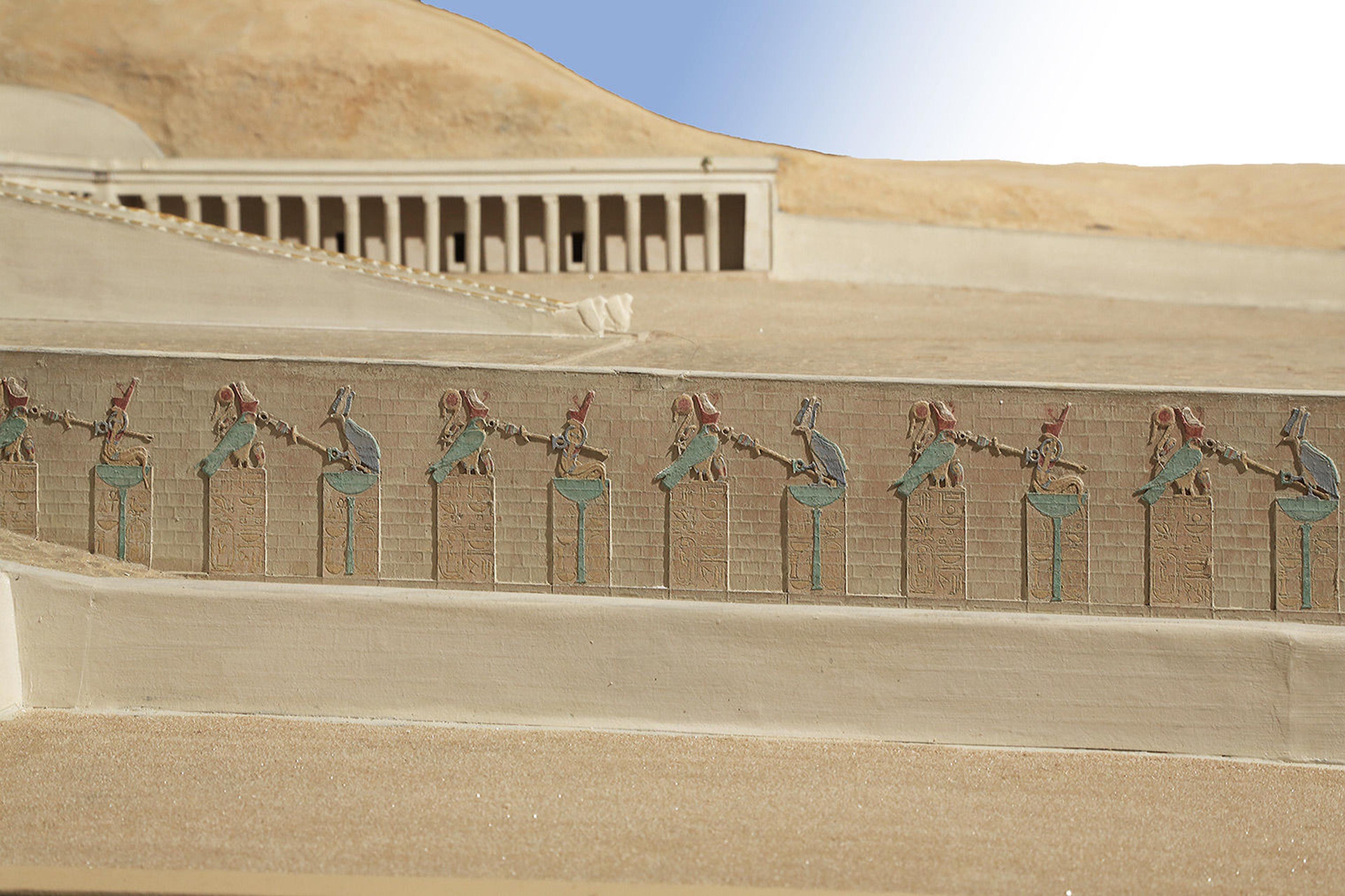

The attempt to manifest Hatshepsut’s position also inspired the designers to articulate the southern front of the lower terrace with a sequence of eleven (originally twelve) pairs of emblematic relief panels, which acclaim the Horus-King Hatshepsut against a background of archaic paneling.

Another innovation of the Hatshepsut era must be mentioned. The Mentuhotep temple was closely connected to the cult of a local Hathor deity but her sanctuary was—as in the pyramid temples of the Old Kingdom—not included in the main building. In contrast, the Hatshepsut temple incorporated large sanctuaries not only for Hathor but also for Amun-Re, Anubis and Re.

Fig. 10 The south side of the middle terrace with the emblematic relief panels. Photograph by the author

The architectural design of the Hatshepsut temple shows an impressive monumental intensity that addresses the admiring or overawed viewer. In other cultures, awesome dimensions, an axial path of approach, symmetry, vast spaces, and endless repetition of identical elements are characteristics of a totalitarian or dictatorial style. While these formal similarities also shape the Hatshepsut temple, the underlying values differ because the pharaonic version stands for the naturally developed, ancient beliefs of a healthy society.

It also has been suggested that the dominant architectural elements of the Hatshepsut temple—the elevation on terraces connected by ramps and the wide, pillared facades—may represent an Upper Egyptian or even specific Theban style, differing from the Memphite tradition. This assumption seems plausible. However, one has to admit that we do not have much information on the design of temples of the Eighteenth Dynasty in Middle or Lower Egypt, so cannot say how much they might differ from Theban architecture.

The Hatshepsut temple inspired the design of two related and similar buildings, the Henketankh for the cult of Thutmose III north of the Ramesseum and the Djeser Akhet of Thutmose III, high above the Hatshepsut temple (see fig. 11).

Fig. 11. East front of the two temples of Thutmose III at Deir el-Bahri and north of the Ramesseum. Reconstruction drawings: Roehrig, Hatshepsut from Queen to Pharaoh, fig. 60.

The architects of the following kings of the Eighteenth Dynasty gradually changed the design of these temple prototypes and assimilated them to the form of deity temples, culminating with the Ramesseum of Ramesses II and the mortuary temple of Ramesses III at Medinet Habu. In the course of this development, the elevation on high platforms was reduced to a modest raise of the floor levels and the Osiris pillar motive disappeared behind huge pylons and was withdrawn into inner courts.

The Hatshepsut temple, or Djeser Djeseru, was built during Hatshepsut’s joint rule with Thutmose III in fourteen to sixteen years, an amazing achievement for the royal workshops considering that many other temples and monuments (e.g. the Karnak obelisks), were erected at the same time. One assumes that the chief steward Senenmut was in charge of the project. When the queen died, only the main and essential parts of the temple had been completed and decorated. The temple cult might have functioned for only twenty years, after which Thutmose III ordered, for unknown reasons, the destruction of Hatshepsut’s statuary and depictions on the temple walls. The most noticeable damage was the destruction of the Osirides. The temple suffered a second wave of destruction during the Amarna period (around 1340 BCE), when the representations of the deities were chiseled out. Some of this damage was patched superficially in the Ramesside period. Over the following centuries, rock falls, stone robbery, and the conversion of the ruin into a Christian monastery reduced the monument to a disfigured ruin. In 1858, Auguste Mariette begun the excavation of the site. Since then, numerous limited attempts have been made to rebuilt the fallen pillared halls, to place back broken wall reliefs, and even to reinstall the colossal Osirides, which had been demolished under Thutmosis III. Since 1961, this restoration project has been expertly accomplished by the Polish-Egyptian Expedition.

Fig. 12. Partially reconstructed “Osirides” on the front of the upper terrace of the Hatshepsut temple. Photograph by the author