Pastel is among the most radiant and fragile of all mediums, and Edgar Degas was one of its foremost practitioners. He was fascinated by female bathers, laundresses, and jockeys because they allowed him to portray the body in motion; he worked and reworked their twisting and turning forms in hundreds of drawings from the 1880s until his final years. His Woman Having Her Hair Combed (ca. 1886–88) has remained one of the Museum’s treasures since entering the collection in 1929, remarkable for its vibrant colors, ambitious scale, and the magnetic intimacy of its subject. It is one of the rare pastels that is almost always on view.

Edgar Degas (French, 1834–1917). Woman Having Her Hair Combed, ca. 1886–88. Pastel on light green wove paper, now discolored to warm gray, affixed to original pulpboard mount, 29 1/8 x 23 7/8 in. (74 x 60.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, H. O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer, 1929 (29.100.35)

Although the composition appears to be in excellent condition, every aspect of it—from the pastel to the colored paper and original pulpboard mount—presents risks of instability and demands careful attention from conservators. Unlike cohesive “paints,” in which pigments are surrounded by water or oil, in a stick of pastel only a minimal amount of binder is present and thus it remains powdery. This loose structure accounts for its unique optical properties, namely the diffuse light reflections that emanate from its irregular surface, as well as its vulnerability to physical damage. “The precious powder,” wrote the French philosopher and critic Denis Diderot, “falls off as easily as scales from a butterfly's wings.” [1]

Left: A box of pastels, such as those Degas may have used. Right: Close-up of Woman Having Her Hair Combed’s irregular surface.

Introduced as a new medium in the fifteenth century, these simple sticks of color underwent a renaissance four hundred years later. The Impressionists were drawn to the medium for its spontaneity, immediacy, and range of chromatic effects; they regarded it as avant-garde because it lacked the gloss of varnished academic painting. These dynamic features, which spoke of modernism, also held great allure to the Havemeyers, Degas’s most ardent patrons.

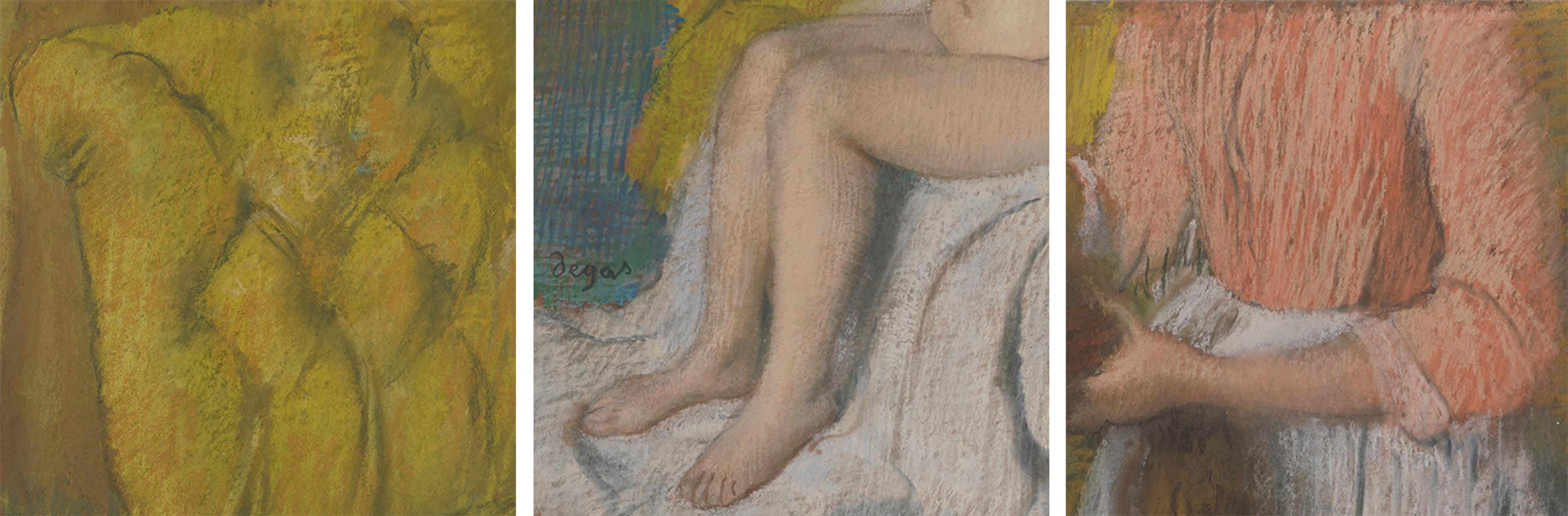

Handling the crayons like drawing tools, Degas employed a range of linear marks, squiggles, zigzags, and stumped powder, building forms in a broad palette of brilliant, complementary hues—oranges and blues, purples and yellows, reds and greens—applied side by side in thick layers or in overlapping vertical strokes that exposed the underlying colors. These juxtapositions produced vivid contrasts far more powerful and strident than the blended and fused passages of traditional pastelists.

Details from Woman Having Her Hair Combed elucidate Degas’s virtuosic handling of pastels, including his application of vivid, complementary hues in overlapping vertical strokes.

Degas practiced at a time when many new synthetic colorants were available, yet they were not always long lived. Their presence in this composition was determined by X-ray fluorescence and other nondestructive means of analysis. Notably, colors in the crimson family, and the aniline-dyed paper that he often used, are fugitive and thus require protection from high light levels to slow or halt the process of fading. This hazard accounts for the subdued illumination in our pastel galleries, a measure that allows us to keep these works on view for longer periods of time.

Woman Having Her Hair Combed on view in Gallery 817 with other pastels by Degas, which require subdued illumination to remain on display. Because of the work’s fragile constituents, the environment must be kept between 68 and 70 degrees Fahrenheit and at 50 percent relative humidity.

The inherent fragility of pastel presents a number of concerns. Works in this medium must be kept under glass or special anti-static sheeting to protect their vulnerable surfaces from contact with objects of any kind. Vibrations must be avoided (on display, in storage, and in transit) because movement risks displacing the pastel powder; thus, these works demand double crating with special cushioning, and hand tools for framing and installation. Fixatives—liquid solutions that consolidate the pastel particles so they will not powder off—cannot be applied, as they darken the pastel and impair its hallmark, high-keyed brightness. Degas never covered entire compositions with fixative but applied it as a barrier in selected areas to layer these fragile colors without displacing the underlying powder.

Like many of Degas’s pastels, Woman Having Her Hair Combed is also threatened by the weakness of its paper and mounting. Degas chose low-quality, machine-made, wood-pulp sheets for their color and rough texture. His mounter wrapped and glued them at their edges to millboard panels made of recycled paper, which provided Degas with a solid surface to work on and enabled him to easily place the finished composition in a frame.

Fluctuating environmental conditions over time have caused these once-resilient panels to grow brittle and warped, exerting tension on the paper that could cause it to tear. However, the mounting was part of Degas’s conception of his pastels as finished works of art. Rather than separate the powdery composition from its backboard, we have chosen to leave the original format intact.